The world’s obsession with Marilyn Monroe will never die. For the latest evidence of this fact, look no further than the much-anticipated Monroe biopic Blonde, which received a 14-minute standing ovation when it debuted at the Venice Film Festival this week. It’s easy to become fascinated with Monroe for all the wrong reasons, to learn the wrong lessons from her life, ideas that motivated Joyce Carol Oates to write the novel on which Blonde is based. Oates sought to look past the superficial persona that enraptured the world and examine how Monroe wasn’t the person everyone tried to make her out to be.

Monroe’s death at the age of 36 granted her a special status in pop culture: She would forever be young, beautiful and sensual. Blonde grapples, by all accounts darkly, with the destructive behavior that led to Monroe’s premature death and America’s unhealthy fixation with her, but there’s another—radically different—film that also deals with the youth- and beauty-obsessed culture that turned Monroe into a goddess.

This week marks the 70th anniversary of the release of Monkey Business, a screwball comedy in which Monroe played a supporting role the year before her star-making turns in Gentlemen Prefer Blondes and How to Marry a Millionaire.

The film follows forty-something Dr. Barnaby Fulton (Cary Grant) as he tries to create an elixir of youth for his elderly employer, Oliver Oxley (Charles Coburn). An accident at the chemical company leads to the genuine product being created without Fulton and Oxley's knowledge, and the watercooler gets tainted with a drug that makes those who take it feel younger. Fulton and his wife Edwina (Ginger Rogers) accidentally ingest the elixir and hijinks ensue. Barnaby, feeling like a 20-year-old, gets his hair cut far too short, buys loud clothes, drives a flashy car, and hits on Oxley’s secretary, Lois Laurel (Monroe). With a teenaged-mentality, Edwina is alternately shy, angry, and mischievous.

As these middle-aged kids (and eventually Oxley) wreak havoc on those around them, Laurel is in the middle of it all, serving, as Monroe so often did in her films, as the embodiment of youth and beauty that everyone who wants the serum aspires to be like or be with. Everyone gets a taste of that youth again and finds it lacking, not because there’s anything wrong with being young or being like Monroe, but because there is something wrong with wanting those things when they’re no longer yours to have.

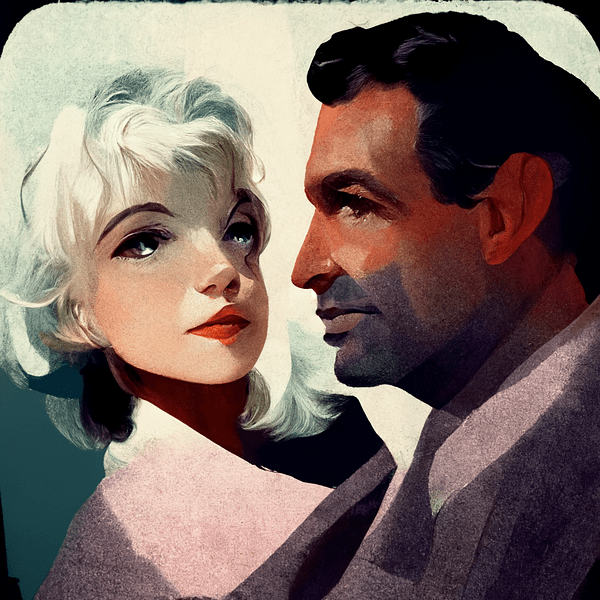

Grant is the perfect opposite for Monroe in a movie that’s essentially a feature length version of the admonition, “act your age.” If Marilyn Monroe is a symbol of eternal youth, Cary Grant is the epitome of aging gracefully. Already in his late 40s at the time Monkey Business was filmed, and still with 10 years of being a romantic lead ahead of him, Grant’s success came not just from his good looks, but his good sense to accept his aging. When Charade came out in 1963, Grant was 59 and his co-star Audrey Hepburn was 34. He was so uncomfortable with the age difference, Grant insisted lines be written in to emphasize his advanced age and that the script be rewritten to make Hepburn the pursuer in the relationship.

Notably, Grant didn’t hit it big in Hollywood until after he turned 33 and while Grant always cared about his appearance, his approach was one of moderation in all things (except for making love, he once quipped.) His fashion advice was to ignore trends and aim for the timeless, making him the perfect star for Monkey Business. When the dignified, middle-aged Grant assumes the garish guise of youth, the contrast between his screen persona and his character under the influence of the formula make Barnaby’s behavior all the more ridiculous.

The only person who pulls off youth well in the movie is Laurel, who, not coincidentally, is the only one who is actually young. Monroe’s youth and beauty are not portrayed as things to aspire to, but they’re not made out to be bad either: They’re simply qualities that exist. Here one season, gone the next. Monroe was smart, and she knew everything one could know about image. While she died young, one can’t imagine that she would have allowed herself to age ungracefully. She once remarked, “I want to grow old without facelifts. ... I want to have the courage to be loyal to the face I've made. Sometimes I think it would be easier to avoid old age, to die young, but then you'd never complete your life, would you? You'd never wholly know you.”

Monroe died young, but it could never be truly argued that she hadn’t lived a complete life. Those who attempt to avoid old age by refusing to accept it when it arrives, on the other hand, will never know what a full life is.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.