Jews and Catholics. Growing up in Massapequa on Long Island, it seemed to me that’s what the world was: Jews and Catholics. I was protected from the knowledge until my late teens that others referred to my town not as “Massapequa” but as “Matzahpizza” because of all the Jews and Italians who lived there.

Even into early adulthood, it was a mystery to me, a Catholic, what a Lutheran, Methodist, or Episcopalian was. Protestants were something from history books, or a general description of a few people we knew whose background we didn’t quite understand. But Jews were clear in our minds, clear in our Bible, clear in history, and clear in our neighborhoods. My hunch is that growing up it was generally more acceptable to marry a Jewish girl than a Protestant one. That’s because, in our neighborhood, Catholics and Jews lived next door to each other. We worked together. We played together. We were on the same teams. We hung out.

Grabbing a piece of matzah off my friend’s kitchen table next door was as common as ringing his doorbell. Its sheer size made it irresistible—who the hell made a cracker this big? Then we’d all go upstairs and put money down on a spinning dreidel while watching the Yankees’ game.

Much of Jewish life I didn’t understand as a kid, but I was around it all the time. Since some people still treat Jews as an alien people—and these last months have brought that home in sickening ways—it still resonates strongly with me because we spent all those days and evenings together in the same neighborhood.

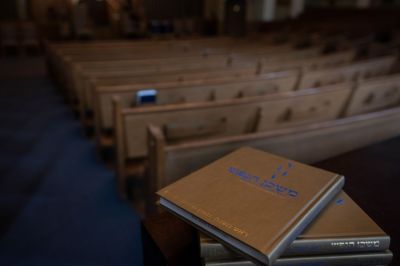

When I was a kid there weren’t as many synagogues on Long Island as there were Catholic churches, but they seemed pretty common. And busy. Fridays were always hopping: people all walking over to services as a family; the windows of the temple lit up from within; guys who never did otherwise, all wearing yarmulkes. Something happened in the synagogue—we just weren’t sure what. I didn’t know what Yom Kippur was either, but each year our friends told us they wouldn’t be around that day. If you forgot and went to their house and rang the doorbell, you’d see everyone inside through the windows, but they’d never come to the door. We Catholics didn’t do anything like that, but we thought it was a pretty cool move. We’re home … but we’re ignoring you.

Sometimes Passover coincided with Holy Week, and it always seemed mysterious to me that all of us brought the religious past right into the present around the same time. It had its limits, though. When you asked your friend when exactly they sacrificed the paschal lamb and put blood over the front door, they looked at you like you were out of your mind. We just assumed the way Charlton Heston did it in The Ten Commandments was the way Passover was still done.

In 1986, when I was around 15 years old, Pope John Paull II made some news when he declared that the Jewish people were still the Chosen People of God, and that they were the elder brothers in the faith to Catholics. On Long Island, that landed without much fanfare. It was like, “Yeah. That makes sense. Let’s get back to shooting hoops, Jacob.”

Jews and Catholics were working things out long before my childhood. The Vincentian priests of St. John’s University passed down the story of the founding of its law school in Brooklyn. The college had opened in 1870 to educate Catholic immigrants and their children. In the 1920s, Jewish fathers came to the Vincentians and told them that their own sons were not being admitted to American law schools because of antisemitism. They asked the priests if they would open a law school that the Jewish fathers would help fund so their sons could become lawyers in America. The Vincentian priests agreed, and thus began St. John’s Law School. That was 100 years ago, not a time one may associate with warm Catholic-Jewish relations. But in New York, it had begun—in the neighborhood.

You would be reminded now and then how different some people’s neighborhoods had been. I was at St. John’s in 1998 when I had the great fortune to meet and talk privately with Elie Wiesel—the writer, Nobel laureate, and Holocaust survivor—when he was presented with an honorary doctorate. As we walked out to his car at the end of the night, he said, “If I could tell my parents that I would be given an honorary doctorate at a Catholic university in America, they would never believe me in a thousand years. In our town in Romania, we walked over to the other side of the street when we got near the Catholic church, and the Catholics did the same when they walked by the synagogue. Amazing!”

Even pop culture seemed to capture this. Mafia films featured mostly Italians—Catholics, of course. But who was right there in the middle with them? Jews. Meyer Lansky. Bugsy Siegel. Murder Incorporated. I don’t know how it played in the rest of the country, but Moe Greene and Hyman Roth being prominent characters in The Godfather movies seemed perfectly natural to me. Plenty of the Jews I knew growing up were tough. I can imagine people in other parts of the country thinking, “Jewish mobsters?” But yeah, Jewish mobsters.

In my 40s I moved to North Carolina, where I was introduced to Protestants in everyday life on a large scale for the first time. Yet the Jews I met here—yes, lots of Jewish folks in the South!—were like a taste of home. Soon after moving, I met up with the local rabbi. After some chit-chat, he politely asked where I was from. “Long Island,” I said, and his defenses immediately dropped. He sidled up, put his arm around me and said, “You and I are going to get along just fine.” I choked with laughter.

Mine is just one limited perspective—probably very specific to neighborhoods in the New York City region of a certain era. Yet it underscores how awful, hateful conflicts of the past can be unfathomable to later generations who don’t see what all the fuss was about. Bitter enemies of centuries can become pals later given the right environment. Certainly no one set out to create Jewish/Catholic friendship—it just happened.

The comedian Sebastian Maniscalco has a bit about him and his Jewish wife. He says of Jews and Italians: “same corporation, different divisions.” We get each other. Even in film and television, Jews and Italians have been playing each other for a long time—proud Queens’ Jew James Cann as Sonny Corleone in The Godfather, and uber-Italian Bronx native Al Pacino has played Jews a bunch of times, most recently as Marvin Shwarz in Once Upon A Time In Hollywood. It’s “a thing.” I don’t know if it was ever officially discussed by casting directors and producers, but it’s real. There’s a sensibility. A feel. Maniscalco does have a suggestion about the food, though: Let the Italians cater Passover from now on.

I am sure lots of people have personal stories of bigotry and prejudice between Jews and Catholics. My own observations of Jewish-Catholic friendship are of course generalizations, but they are generalizations I know to be true. So is the fact that when Jews come under attack simply for being Jews, the neighborhood code rises up fast in the heart. It’s not paternalism, nor is it sentimentality. It’s kinship, and it can be fierce.

If you’d like to see it in its instinctual, natural, unadulterated form, watch the video of “Paulie” of New York back in October. When he came across a man in Forest Hills, Queens, tearing down flyers of Jews kidnapped in Israel on October 7, Paulie educated the man on life in America—New York style. Angry, loud, profane, and with a touch of “You wanna do something about it?” Do I know he was Catholic? Can I prove he was Italian? No. But I mean, come on. Like recognizes like.

I realized something about Catholics when I moved to North Carolina that I never had a chance to understand when surrounded by fellow Catholics in New York. When members of other Christian denominations stop going to church, practicing, or believing, they generally stop saying “I’m Lutheran,” “I’m Methodist,” or “I’m Episcopalian.” Catholics, on the other hand, might not have seen the inside of a church for decades, or said a rosary in their lives. They may even scoff at the very idea of God. But if asked, or presented with a form requiring religious information, the faithful work of Sr. Mary Francis generations ago arises in the blood, and I’ll be damned if they still don’t check the box that says Catholic.

I know that my Jewish friends understand. Hell, I’m sure we learned it from them.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.