When Donald Trump picked J.D. Vance as his vice presidential running mate back in July, the predictable scrutiny a vice presidential nominee typically gets quickly devolved into a very online spectacle.

Desperate journalists rifled through the Ohio senator’s digital trash, analyzing it and then analyzing it again in search of past misdeeds. They were captivated by Vance’s X follows, which included the right-wing social media personalities Raw Egg Nationalist and Bronze Age Pervert—both of whom boast more than 100,000 followers and are frequent subjects of criticism and admiration alike. A Wired piece perused Vance’s public Venmo account, revealing that the senator sometimes used joke names for his transactions. Vanity Fair and the Daily Dot even reported on Vance’s Spotify account. The big reveal? Vance liked, in Vanity Fair’s words, “globalist favorite” Bono, the U2 frontman with tens of millions of fans around the world.

The whole thing was, to borrow a word that’s recently been in vogue, weird.

A vice presidential nominee is obviously expected to be in the public eye, but the way Vance’s online past was examined felt less like mainstream political vetting and more like the dirty work of online “stans” looking to learn every detail about the object of their fixation. Combing through music playlists and cash app transaction histories, desperately searching for cryptic messages that might speak to a person’s character, is the work of a 14-year-old obsessed with Rosé, Chappell Roan, or Sabrina Carpenter, not a reporter. Moreover, these supposed deep dives into Vance’s online detritus yielded no deeper, more meaningful information.

But they did preview a potential future of politics in increasingly online times. As millennials enter their 40s and assume elected office—bringing along years of likes and follows and posts—we should expect more of these types of intrusions, not all of which will be as ridiculous and meaningless as the Vance affair. And given the parasocial relationship much of our culture has with the internet, we should anticipate these intrusions to only get, well, weirder.

A landscape beyond gaffes.

While politicians have always adapted to new communication technologies, the internet represents a seismic shift in personal use and public-facing personas, as well as in their relationship with constituents. At a basic level, these changes leave politicians prone to embarrassing moments, like Ted Cruz’s accidental pornographic “like,” back when X was Twitter and likes were public.

But the revelations of somebody’s online history may not be interpreted as mere gaffes for too long. We are on the verge of a new albatross across all aspiring politicians’ necks because—let’s face it—who thinks before they post on the timeline or in the group chat? Who’s considering whether a Spotify playlist will be seen as just a Spotify playlist or as a telegraph of something deeper, darker, and disqualifying for public office? Put another way: We don’t only do everything online, we’re always online. And we’re not always thinking about what we’re sharing.

With those stakes in mind, the prescient observation from the author and LGBT activist Dan Savage during Anthony Weiner’s sexting scandal—that we all carry “a porn production studio in our pocket”—barely scratches the surface. We’ve got bigger, much more exotic fish to fry than sexual impropriety with a paper trail (well, maybe except for RFK Jr.), from YouTube watch histories and Reddit questions, to embarrassing online phases, to archives of our social media posts. The online paper trail of future politicians will be more perplexing and personal than, say, leaked emails.

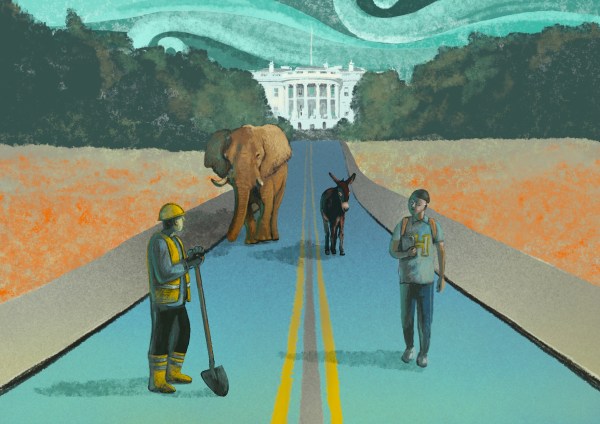

And then there’s the thorny issue of how the rest of us will relate to politics as both viewers and voters. After all, this changing political landscape as a result of the prevalence of the internet has coincided with the twin phenomena of public fandomization and private hobbyfication of politics.

The fandomization of politics.

“Fandomization” is best understood as the way politics increasingly resembles fan culture. Just as fans of a TV show or musical artist might form communities, create fan art and fan fiction, buy merchandise, and defend their favorite characters, similar behaviors are seen in politics.

Abigail De Kosnik was one of the earliest scholars to make the comparison between fan culture and political culture in her paper on the 2008 Democratic primary. In it, she writes:

Politics resembles entertainment. Both political events and media texts produce stars, narratives, climactic incidents, supporting players, supplemental materials, and, among citizen-consumers, fans who form interpretive communities.

While the intertwining of politics and entertainment is not new, the internet has dramatically amplified their fusion, obliterating the boundary between public and private in the process.

But it’s not just that constituents have become fans—politicians have also leaned into their role as “fan objects.” Where they once had to worry about celebrity, politicians now must concern themselves with internet celebrity. It’s a different beast altogether: faster-paced, requiring greater investment in the online “machine,” and demanding increased literacy in an ever-evolving media environment. Being good on TV is one thing; maintaining a TikTok or Instagram presence is another.

Successful politicians at the national level—the kind running in a presidential primary or general election—must now essentially be influencers, communicating directly to their fans without intermediaries and cultivating personal brands across multiple platforms to reach sufficiently large audiences. If they’re lucky, their fans will help them, but they need to know how to read their cues. Politicians must also navigate online subcultures while remaining legible to the remaining populations for whom those subcultures are foreign. And they must be conversant in the language of virality and memes.

But requiring that a politician (or anyone, for that matter) be an internet personality to succeed comes with risks that go far beyond the privacy concerns of tabloid journalism or finding your best angles for television. The pressure to maintain a constant online presence can lead to, well, dumb posts, frustrating tunnel vision about what is and isn’t relevant, and unnecessary and often public meltdowns.

Not everyone is cut out for it. People have been writing think pieces about Sen. Chuck Grassley’s frankly bizarre social media presence for nigh over a decade. Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, on the other hand, may be as well known as she is at least in part because she finessed the online world so skillfully. Her celebrity far outshines her relatively junior political position in Congress—or anything she’s accomplished for that matter.

Donald Trump and Kamala Harris exemplify edge cases in this broader phenomenon, even if their campaigns have launched successful online brands. They both have a secret quality many others lack: They are naturally memeable. Whether it’s “many such cases” or “you think you just fell out of a coconut tree?” both have a special quality to them. (Especially Trump, who’s had a bigger influence on the English language in the last decade than every Hollywood blockbuster, influencer, and pop star combined.) It’s a quality that can’t be faked, as Gov. Ron DeSantis discovered. Their fans eagerly amplify and spread their messages, maintaining their online personas for them. Trump commands both a fandom rivaling Taylor Swift’s and an active anti-fandom of obsessive haters, exponentially expanding his reach.

Media scholar and grandfather of fan studies Henry Jenkins’ concept of “participatory politics” offers another perspective on politics as fandom. Jenkins describes how younger generations, raised in a participatory social media culture, expect to have a voice in political discussions and decisions, often rejecting traditional hierarchies and demanding more direct involvement. In Jenkins’ assessment, this online environment lends itself to fandom. It empowers grassroots organizing and rapid mobilization of supporters. User-generated content, such as memes and videos, shapes political narratives and public opinion, much like fan art and fan fiction in other fandoms.

The hobbyfication of politics.

The “hobbyfication” of politics, a closely related but distinct phenomenon, has further complicated the situation. As internet subcultures spawn or amplify increasingly niche political identities—like the anarcho-communists, cyber-nihilists, and agrarian voluntaryists profiled by internet researcher Joshua Citarella, just to name a few—we’re witnessing a fragmentation of the political spectrum that transcends traditional left-right divisions. Politics has become a form of identity-based consumption, with individuals experimenting with esoteric beliefs, and crucially, both in much higher numbers and with a paper trail. For example, on Reddit alone, /r/DarkEnlightenment—a subreddit dedicated to the once-obscure political philosophy of neoreaction—has 25,000 subscribers. Similarly, /r/anarchocapitalism has 196,000 and /r/anarcho_primitivism has 8,600. And these are just three examples.

Experimenting with radical ideologies in your youth is nothing new. But how do you defend “going through a phase” when that phase has ample evidence online?

Going through a phase in the internet age isn’t the same as going to a few in-person meetings or reading a few obscure books without anyone knowing a thing about it. For many, it’s a form of performative engagement, a mix of roleplaying and experimentation. The use of extremist language can even be a form of gatekeeping, where people use purposely off-putting language to protect the boundaries of their online subculture from “normies.”

Sometimes members of these online groups even use extreme language to reach moderate conclusions, and their language choice is a way to signal to particular groups of people. You see this often on X and TikTok. People use the most extreme language of their particular tribe not to signal a genuine commitment to, say, a revolution in service to “fully automated luxury space communism,” but rather to tell the reader that they’re Democrats voting for Kamala Harris. This type of hyperbole is, in some ways, an inversion of dog whistling, where extreme language becomes a wink to more moderate, acceptable actions said in an edgy, countercultural way. Determining which one is which is highly contextual, though. (Sometimes, you really do want communism in space and are willing to fight to get it.)

But the boundary between private musings and public declarations on platforms like Twitter, Instagram, or Reddit is increasingly blurred, especially when hiding behind the veil of anonymity or pseudonymity. As politics becomes increasingly intertwined with everything in American life, labels like “communist” or “fascist” are more susceptible than they were before to becoming badges of teenage rebellion or countercultural signaling.

For young people, the language of radicalism has always been a tool for identity formation or a way to shock adults rather than reflecting deeply held beliefs. It’s just that now, these moments are captured forever, waiting in a screenshot library somewhere to be weaponized against you.

As millennials ascend to positions of power, we will face increasing questions about which aspects of a politician’s digital footprints warrant attention and how to interpret them in the context of youth culture and development.

So what will we do? Will we develop a more nuanced understanding of online behavior that distinguishes between youthful experimentation and genuine ideological stances? Will the bar for what counts as an embarrassing, or worse, disqualifying digital footprint become higher?

We may not have a choice.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.