Chag Pesach Sameach! Or Happy Passover! Our Jewish friends and neighbors may be hearing these words as we enter the weeklong Passover festival. While enjoying their Seder plates and matzos, they may also remember what this important Jewish holiday is about: the exodus of the Israelites from slavery in Egypt, as described in the Hebrew Bible, especially in the book of Exodus.

Meanwhile, our Christian friends and neighbors may relate to Passover from a different angle: This Jewish holiday serves as a foundation for understanding the last supper and the sacrifice of Jesus—metaphorically referred in Christian theology as the “Passover Lamb.”

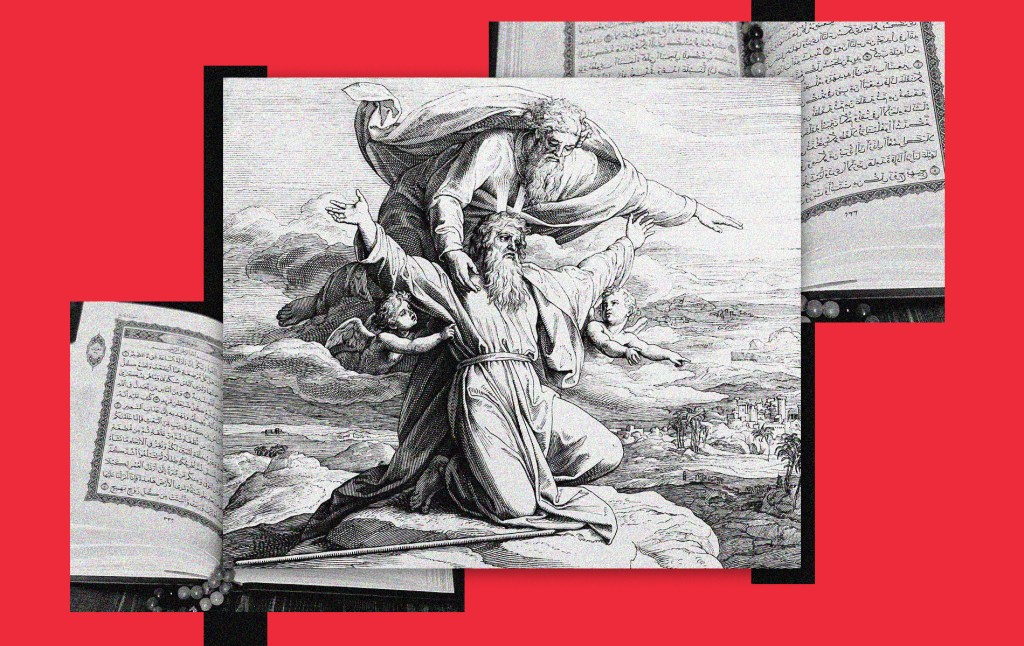

Yet there is another religion whose founding narratives are also deeply connected to the story of Passover, though this third leg of the Abrahamic triangle has received far less attention in the West: Islam, my own faith.

In fact, the central theme of Passover is so fundamental to Islam that it is the most frequently mentioned story in the entire Quran.

As a student of the Quran, I had my aha! moment about this Judeo-Islamic connection many years ago when a Christian friend asked my advice for a good English translation of the Islamic scripture. I was happy to see my friend’s interest in my faith, and advised him to get his hands on The Qur’an: A New Translation by Muhammad Abdel Haleem. Several weeks later, my friend wrote back. He had indeed bought a copy of that translation and read much of it. He was touched by the teachings of piety and ethics he came across, while puzzled by some other themes. He was also, as he put frankly, a bit troubled by some combative verses—but only to recall, in fairness, that his own scripture, particularly the Old Testament, had similarly harsh passages.

“But do you know what the biggest surprise was?” my friend wrote at the end of his long email. “That I was expecting to read about the life of Muhammad. But, instead, I read about the life of Moses more than anything else.”

He wasn’t exaggerating. The Quran indeed narrates very little about its own messenger, the Prophet Muhammad, at least in an explicit way. In more than 6,000 verses that make up 114 “surahs,” or chapters as we will call them, the name Muhammad appears only four times. When you read the whole Quran, you learn almost nothing about his birth, his upbringing, his early life.

On the other hand, Moses dominates the Quran. His name is mentioned 137 times—by far more than any other human. His story is narrated in some 70 passages dispersed throughout 34 chapters. They touch on so many Mosaic themes—from his birth in peril, to his leadership of the Israelites, to his defiance of Pharaoh, to his amazing miracles.

And, after Moses, guess who may be the second most mentioned human being in the whole Quran? I ask this question to friends, and they come with good guesses: Maybe it is Abraham? Or perhaps Jesus, or Noah?

No, no, and no. While these biblical figures are indeed narrated and praised in the Quran, the second most mentioned human being in the Islamic scripture is Moses’ nemesis: Pharaoh. That is because the struggle between the two men, and the liberation of the Israelites from the yoke of Pharaoh, is a story that the Quran narrates in great detail and even repeatedly—most noticeably in chapters such as Al-A‘raf (7), Ta-Ha (20), and Al-Qasas (28).

In these passages, we read a story that is largely similar to the biblical story of Exodus: Israelites, the quintessential monotheists, were enslaved in Egypt. They were tormented by Pharaoh, who was “slaughtering their sons and sparing their women.” But God wished to “favor those who were oppressed in that land, to make them leaders, the ones to survive” (28:4-5).

That is why God, the Quran also tells us, raised Moses as prophet for the Israelites, to lead them and save them from the Pharaoh. Moses is born at a time when the Egyptian tyrant has ordered the killing of all male Israelite infants. To protect him, his mother places him in a basket and sets it afloat on the Nile river. He is found and adopted by Pharaoh’s wife, who raises him as her own.

Then the Quranic Moses grows up, and accidentally kills an Egyptian man. Fearing for his life, he flees to Midian, where he marries and lives in exile. Years later, he sees a “fire” on a mountaintop, where God speaks to him, and commands him to return to Egypt. Moses, along with his brother Aaron (Harun), is tasked with confronting Pharaoh and demanding the release of the Israelites. God tells them: “Go and tell him: ‘We are your Lord’s messengers, so send the Children of Israel with us and do not oppress them. We have brought you a sign from your Lord’” (20:47).

It is interesting that in the Quran, while speaking to Pharaoh, Moses calls God “your Lord.” He makes this point emphatically: “He is your Lord, and the Lord of your forefathers … Lord of the East and West and everything between them” (26:24-26). That is a different emphasis from the Bible, which speaks repeatedly of “Lord, the God of the Hebrews.” As the Pulitzer-winning theologian Jack Miles pointed out in God in the Qur’an, the difference between the two scriptures here reveals two different conceptions of God—Yahweh and Allah:

Yahweh does not want to convert Pharaoh into a Yahweh-worshipper. He does not want to tell Pharaoh anything through Moses … [In contrast] Allah wants to convert him.

And that difference, in my view, also reflects the fundamental difference between Judaism and Islam. They are both Abrahamic religions built on staunch, unitarian monotheism. But while the former addresses the Jewish people, the other one addresses all people. One is a national monotheism, the other is a proselytizing one.

The biblical and quranic stories of Exodus have other parallels: In both, Pharaoh’s rejection of Moses’ call brings divine wrath on Egypt. “So We let loose on them the flood, locusts, lice, frogs, blood,” says the Quran’s divine voice (7:133). Conspicuously, however, the Quran does not mention the 10th plague, from which the very word “Passover” is derived: the killing of the firstborns of the Egyptians, during which the Israelites were spared thanks to the lamb’s blood on their doorposts, causing death to “pass over” them.

That is why Passover itself is actually not recognized in the Islamic tradition if merely understood as a reference to the 10th plague—the death of all the firstborn sons in Egypt But the rest of the biblical story of Exodus is remarkably present in the Quran. The latter also narrates the Israelites’ escape from Pharaoh’s army, and the latter’s destruction in the sea after its miraculous parting by Moses. That is how, the Quran says, God finally saved the Israelites:

Your Lord’s good promise to the Children of Israel was fulfilled, because of their patience. And We destroyed what Pharaoh and his people were making and what they were building. (7:137)

One can wonder, at this point, why this biblical story of the Israelites was so important for the Quran, which emerged almost 2,000 years later, in seventh-century Arabia, addressing a totally different people: the Arabs. The answer that I offer in my book The Islamic Moses, is that those first Muslims, the followers of Muhammad, identified themselves with the Israelites. They, also, were monotheists who were persecuted by a pagan people—the polytheists of Mecca—and they also yearned for liberation. Thus the biblical story of Moses became an archetype for their own journey. And the Israelite exodus from Egypt became a template for their own hijrah, or migration, from Mecca.

Which points to a greater truth: Islam, just like Christianity, is deeply intertwined with Judaism. As the late, great Jewish historian Shelomo Dov Goitein once put it, Islam is even “from the very flesh and bone of Judaism. It is, to say, a recast, an enlargement.” This is also why, just as there is a “Judeo-Christian” tradition familiar to most Americans, there is also a “Judeo-Islamic” tradition, as dubbed by another esteemed Jewish historian, Bernard Lewis.

Today, unfortunately, the Judeo-Islamic tradition is much forgotten. Instead, many people can imagine only enmity between Jews and Muslims. The painfully obvious reason is the Arab-Israeli conflict, which caused much pain to both sides for three quarters of a century, and escalated to its worst phase since that doomed day of October 7, 2023.

But the Arab-Israeli conflict is a political struggle over land—not a war of two religions. If we merely looked at those religions, Judaism and Islam, we would find fascinating parallels. We could even find inspirations for finally achieving, someday—if God grants us His mercy—peace.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.