The story of the Hebrew Bible, it always seemed to me, follows an uneasy relationship between an obstinate people and an irascible God. In an epic that spans hundreds of years, their relationship sees adoration and alienation, devotion and betrayal. On one occasion, the father of the nation, Jacob, quite literally wrestles God into submission (for which God names him Israel, “he who fought God”). On many other occasions, God comes within an inch of exterminating Jacob’s descendants. The story almost begs to culminate in a devastating theomachy that consumes the world and unmakes creation. But it doesn’t. Rather, the story tells of how the God and people of Israel tame each other through the Law.

This weekend was the first night of Passover. The dinner—the Passover Seder—is a symposium of reclined interrogation and narration, a ceremonial retelling of a liberation story: the exodus of the children of Israel from Egyptian enslavement. With salt-dipped greens we recall the bitter tears of the Hebrew slaves, and with four glasses of wine we rejoice in their escape into freedom and national independence. A genocidal pharaoh. An infant in a reed basket. Preternatural fire burdening a shepherd with unwanted leadership. “Let my people go.” An escalation of plagues and, after that, a partable, vindictive sea.

No doubt, God’s great and terrible wonders that delivered the Hebrews from slavery and toward their Promised Land deserve their annual recounting. But for Jews, liberation itself isn’t the culmination of the story, but the prelude. The exodus reaches its true climax 50 days later on Mount Sinai, where God reveals Himself to his freed nation in order to lay down the terms of a new social contract.

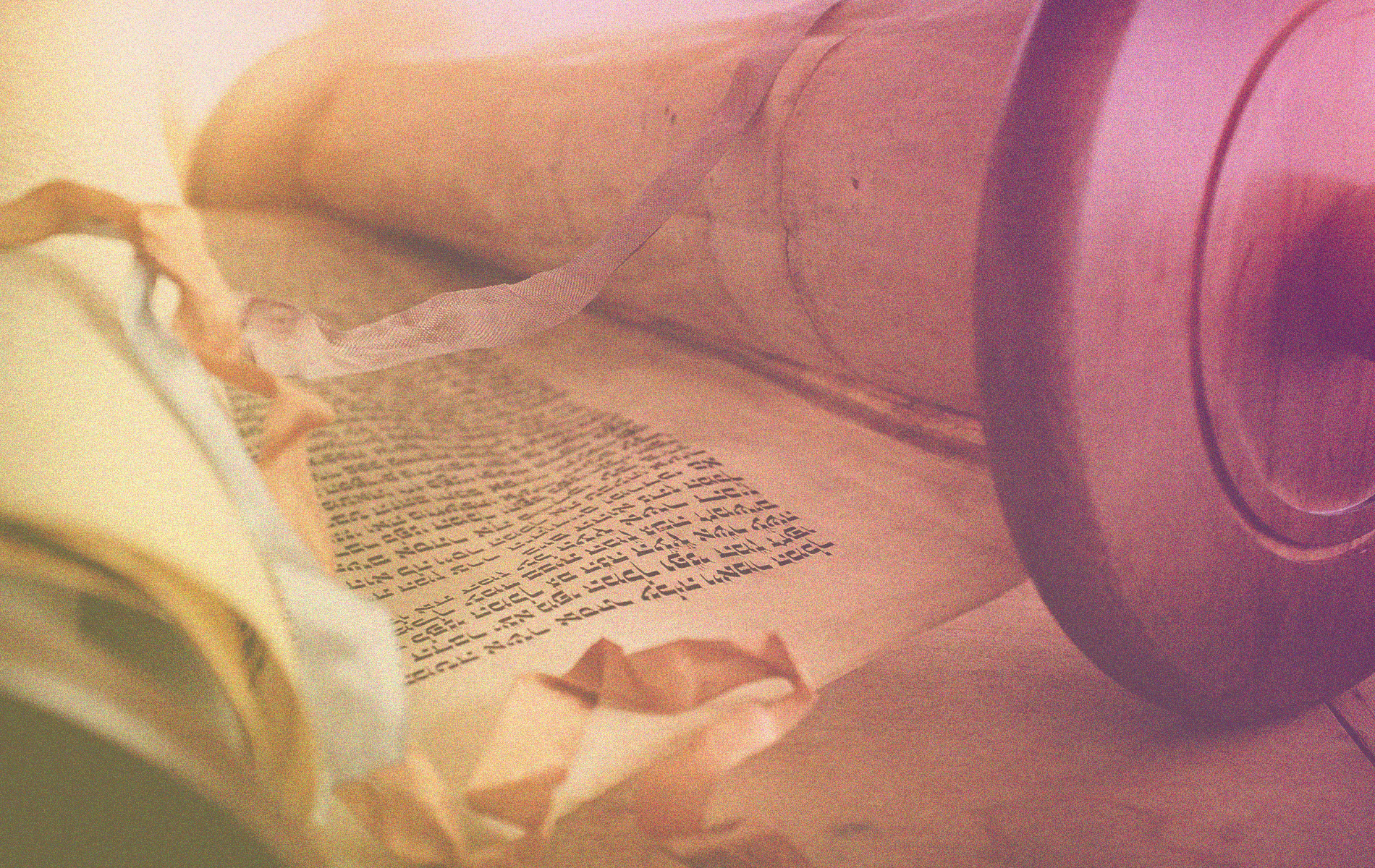

More than the miracles, or the crossing of the Red Sea, or the revelation of God in the desert (His presence was already ubiquitous!), it was receiving God’s Law—the Torah—that turned 12 tribes into a free nation.

The Law is the bedrock of the Jewish people and their relationship to the divine. A national constitution drafted by God and ratified by the people, obligating both. For the Israelites lost in the desert, the Law was a guide for surviving the burden of independence. It demanded of them to restrain their stubborn, defiant nature, while creating a system of ordered liberty. But for God, the Law meant something far more radical: a self-imposed limit on his own infinite sovereignty. From now on his monarchy will be covenantal (constitutional!), not absolute. Not tyrannical.

The role of the Law.

Was God a despot before giving the Law? Well, yes, in a way. Tyranny is often understood as a regime of too many heavy-handed rules, overregulated, overlitigated, overjudged. But the harshest tyranny, true totalitarianism, isn’t an excess of laws, but lawlessness. In a lawless society, absolute power—arbitrary power—reigns, pulling everyone into its gyre, corrupting them all absolutely. Virtue may be rewarded or it may not. Crime may be punished or it may not. Virtue may be punished while crime is rewarded. Nothing but a formless void, darkness over the face of the deep and arbitrary Will hovering above.

The Hebrew God, whom Harold Bloom observed to be possibly the most challenging character in the Western canon, is the ultimate absolute power. Total, all-knowing, and all-powerful, the Hebrew God cannot be contained in the deepest earth or in the highest heaven, let alone in the mind and morality of mortals. To fathom the Jewish God, a friend of mine once joked, try imagining the cosmic horror that would make even the worst Lovecraftian enormity tremble in terror. How can the nature of God seem anything but arbitrary in the eyes of man?

Without the Law, humanity had to rely on personal appeals to God for justice. Abraham bargained for the fate of Sodom by admonishing God (“will the judge of all the earth not do trial?”), and Moses used “what will the neighbors think” logic to manipulate Him into sparing the idolatrous Israelites (“should the Egyptians speak and say, For mischief did he bring them out?”). But such appeals depend on divine caprice. They can be answered with justice or mercy, but just as easily with wrath or with indifference. Just ask Job.

The covenant at Mount Sinai marked an end to arbitrary justice and to the absolute monarchy of the Heavens. The God who cannot be contained in the Heavens bound His infinite self to the Torah. There was now to be Law, and no one, not even God—its author and ultimate judge—gets to stand above it. Not even God gets to play tyrant.

Freedom after the law.

Biblical scholar Richard Friedman sees in the Hebrew Bible a story about God’s gradual disappearance, or rather, withdrawal, from human affairs. If in Genesis God walks among His creation in the Garden of Eden, by the books of Ezra and Nehemiah He rarely shows His face. In the scroll of Esther He isn’t mentioned once. God gave the Law to Israel with a grandiose display of His power on earth. But having done so, he started receding, passing on to mankind the responsibility and the tools to work things out on their own. By parting the Red Sea, God kindled the idea of liberty, but only on Sinai did He deliver. Free from both the cruelty of Pharaoh and the totalitarianism of God, the children of Israel were left alone to study, adjudicate, and administer the Law. They had to learn how to self-govern.

That’s what the Jewish Talmud is about. Peruse any of its tomes and you’ll immediately recognize the Talmud is neither a simple religious text, nor a cipher of mystical gnosticism (nor a self-help manual for business entrepreneurs). It’s a codex of legal disputes between Jewish scholars about the evolving interpretation of the Law. It may seem to some like a pedantic obsession with a dead letter. But it’s the Talmud that kept the Law alive through generations of relentless, eristic study. In the world of jurisprudence, the children of Jacob are still wrestling with God.

This theme is at the forefront of a famous Talmudic tale. A savant rabbi passionately challenges his fellow judges on the Jewish court over some halakhic quibble. Despite his erudition, and though he “makes all the arguments in the world,” the other judges reject his interpretation. Indignant, the rabbi asks God to intervene. Minor miracles ensue, but to no avail. Finally, a voice descends from on high and declares the rabbi’s interpretation correct. Yet the court doesn’t budge: It has reached its decision according to the judicial process stipulated in the Torah. Their ruling is therefore constitutional and binding, divine intervention notwithstanding. “It is not in the Heavens,” one judge concludes. The heavens, in other words, will not be allowed to inflict themselves on human justice on a whim. Hearing this, God laughs. “My children,” He chuckles, “have triumphed over me.”

On the night of the Seder, we gather with family and friends to celebrate the miracle of liberation; how the God of history broke the world with his wonders to deliver the children of Israel into freedom. But on all other nights we will remind ourselves that it’s through the Law that we learn how to guard that freedom from tyrants high and low, how the work of doing so is never ending, and that it falls entirely to us.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.