Democrats are in a truly awful state today, with a recent approval rating of just 37 percent. California Gov. Gavin Newsom last month labeled the Democratic brand “toxic,” and his fellow Democrat, Pennsylvania Sen. John Fetterman, has warned, “if we don’t get our sh-t together, then we are going to be in a permanent minority.”

If the party’s fortunes sound hopeless, it’s worth remembering the far more dire straits that Republicans found themselves in nearly a half-century ago.

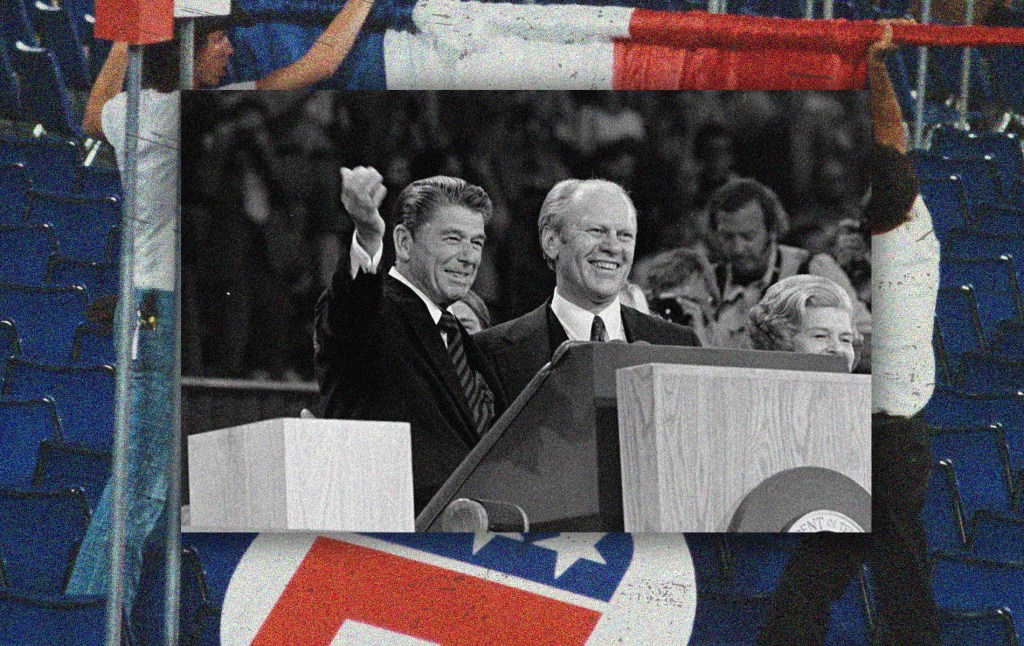

In the runup to the 1976 presidential election, the fallout from the Watergate scandal and Ronald Reagan’s primary challenge to President Gerald Ford so roiled Republicans that some high-profile party members and media figures were openly predicting the GOP would go the way of the Whigs.

“There have been warnings from Republican leaders that the party might not survive its present wrangling,” Walter Cronkite solemnly announced in a newscast that year. Maryland Republican Sen. Charles Mathias questioned whether the party had a future and warned, “The fate of the two-party system may hang in the balance.”

Of course, just four years later, Reagan would win a landslide victory over President Jimmy Carter, ushering in a conservative revival. Today, despite the Democrats’ anemic poll numbers, lack of a standard-bearer, and ideological conflicts, there’s still hope for the party—especially with President Donald Trump’s massive tariffs leading to a Wall Street meltdown and prompting fears of a recession.

We are already starting to hear rumblings from some Republicans about the negative electoral consequences that Trump is inviting for the party by pursuing an economic agenda that could inflict higher prices on inflation-stressed voters. Kentucky Sen. Rand Paul warned that tariffs historically have “led to political decimation,” pointing out, among other examples, that Republicans lost half their seats in the 1890 House elections after Congress passed then-Rep. William McKinley’s Tariff Act. The defeated House Republicans included McKinley himself, although he would rebound to win the presidency in 1896.

When the party in power overreaches, as Republicans are arguably doing now, that often leads to a backlash. And even before Trump announced his tariffs, the liberal candidate’s resounding victory in a high-profile Wisconsin Supreme Court race was already providing evidence of the physics of American politics, which have long shown how quickly a party’s political prospects can reverse.

That was especially true in the volatile 1970s, which started with President Richard Nixon pulverizing Democrat George McGovern in the 1972 presidential election. But just 15 months later, the spreading Watergate scandal already was prompting questions about the GOP’s viability. At an awards dinner in Washington in January 1974, then-Vice President Ford presented Reagan with the “Mr. Sam” Award, named for the late House Speaker Sam Rayburn and awarded to a “governmental figure” making a special contribution to sports. Amid speculation that the California governor would battle Ford for the ’76 nomination (awkward!), a reporter asked Ford if the GOP nomination was even worth winning. “You’re darn right it is,” he snapped.

But even some party leaders acknowledged the sense of doom.

“Unless you and I get together and work for this party, we may have no party at all,” Republican National Committee Chairman Mary Louise Smith warned in a 1975 speech.

On May 31, 1976, as Reagan continued his insurgent run for the GOP nomination against a sitting president, the New York Times ran a photo of him at the top of the front page, waving astride a horse. But the headline below it belied the smiling image: “Some Republicans Fearful Party Is on Its Last Legs.”

“Is the Republican Party over?” reporter James Naughton asked in the story. “Divided by a contest for its Presidential nomination and debilitated by the events since the last national election, the party may face a new disaster in November and perhaps beyond.”

At the time, there was still a distinct liberal wing of the Republican Party, represented by politicians such as Vice President Nelson Rockefeller. Reagan’s candidacy was an attempt to move the party firmly to the right. As Naughton wrote, “Young progressives spoke dejectedly of the 1976 campaign as their ‘last hurrah’ as Republican activists. Conservative purists described specific contingency plans aimed at ‘destroying the Republican Party’ as a means to create a new major party. And campaign professionals beholden to neither ideological wing said they feared the party might do no more than ‘stagger along as a cripple’ for another decade.”

Hard-right conservatives like Richard A. Viguerie, the pioneer of direct-mail political action campaigns, said the party wasn’t a viable vehicle for people like him. He compared the GOP to a disabled tank on a bridge during wartime: “You’ve got to take that tank and throw it in the river.”

“Pessimists thought of the GOP as a ball of yarn—with conservatives pulling one thread by threatening to form a new, “ideologically pure party” if Ford won the nomination, and moderates ready to pull another thread by withholding their support from Reagan if he was the party's nominee, as they did in ’64 with Barry Goldwater.”

Meanwhile, moderate GOP consultant John Deardourff warned that nominating Reagan would hasten the death of the party, which he said was already reeling from terrible branding. The national party brand was so toxic after Watergate that Minnesota Republicans changed their name to the “Minnesota Independent Republican Party.” (They dropped the “Independent” label in 1995.)

Deardourff said that old voters associated Republicans with Herbert Hoover and the Great Depression, while for younger voters, the GOP carried the stench of Nixon and Watergate.

In that same New York Times story, even Sen. Bob Dole, a former national party chairman, acknowledged that Republicans were on the ropes. “You’d think the only way to go is up, but not necessarily,” he said, a couple of months before Ford chose him as his running mate to replace the more moderate Rockefeller. “I’m not a doomsayer—yet.”

Pessimists thought of the GOP as a ball of yarn—with conservatives pulling one thread by threatening to form a new, “ideologically pure party” if Ford won the nomination, and moderates ready to pull another thread by withholding their support from Reagan if he was the party’s nominee, as they did in ’64 with Barry Goldwater.

“In scientific terms, the Republican party is verging on critical non-mass,” conservative analyst Kevin Phillips wrote in a December 1975 column. “If it gets much smaller, it cannot hold together.”

Despondency set in as the party met for its convention in Kansas City, Missouri, in August 1976. The numbers were staggeringly terrible: A Gallup poll taken before the convention found just 22 percent of Americans identified as Republican, compared to 46 percent who said they were Democrats. An earlier New York Times poll found that 4 out of 10 of people who called themselves “Reagan Republicans” would vote for Carter over Ford. There were only 13 Republican governors at the time, and Democrats had big majorities in both houses of Congress.

However, those polls didn’t suggest a liberal shift. The Gallup poll found that 49 percent identified as conservative, just more evidence of the party’s mismatch for the right. It also supplied ammunition for those disaffected Republicans agitating for a new party.

“For the first time at a GOP convention, there is serious talk among Republicans that the Grand Old Party may be doomed no matter what happens, that it is steadily withering away much like the Whigs in the 1850s,” the Wall Street Journal reported in an August 19, 1976, story—one of a host of comparisons made to that vintage political party.

The Journal noted that polls showed Democratic candidate Jimmy Carter with huge leads over both Ford and Reagan in a general election matchup—a striking and misleading snapshot in time, given Carter’s narrow win over Ford later that year and his lopsided loss to Reagan four years later.

In a Washington Post column headlined “The Great Shrivel,” Rod MacLeish used a word to describe the Republicans’ sorry state that would become more synonymous with Carter’s presidency. “It will take a few more Republican conventions before we know whether this is a temporary malaise or whether the GOP has that myopic fever that killed the Whigs, thus making possible the birth of the party that now brawls and sickens in Kansas City,” MacLeish wrote.

Although the presidential election that fall was close, the Republicans found themselves in tatters across the board on election night. They emerged with just 12 gubernatorial seats and 38 senators in the next Congress. Still, the ’76 convention, far from signaling the death of the party, reinvigorated it by putting Reagan conservatives on the ascent, paving the way for his historic victory four years later. In a memorable line at the ’76 convention that rallied supporters, Reagan said, “I believe the Republican Party has a platform that is a banner of bold, unmistakable colors with no pale pastel shades.”

But even by 1980, some Republicans were still fretting that the party would screw up the chance to regain the White House against a deeply unpopular incumbent by nominating someone as conservative as Reagan. One of those concerned Republicans was Ford, who was hoping party leaders would urge him to run again.

“Every place I go and everything I hear, there is the growing, growing sentiment that Governor Reagan cannot win the election,” the ex-president told the New York Times in March 1980, adding that people warned him “that we don’t want, we can’t afford to have a replay of 1964,” referring to Goldwater’s shellacking at the hands of President Lyndon B. Johnson. “A very conservative Republican can’t win a national election.”

That didn’t stop Ford from toying with becoming Reagan’s running mate at the 1980 convention. But Ford sought more power than what a VP normally commands, and the idea fizzled when the Reagan and Ford camps couldn’t reach an agreement.

Today, while no one is predicting the end of the Democratic Party, some of their allies are channeling the dismal spirit of ’76. “The D next to a candidate’s name too often stands for disqualified, demoralized, distrusted and disconnected,” said Jonathan Cowan, president of the center-left think tank Third Way, earlier this year.

But one of the most prominent voices on the right, Ben Shapiro, co-founder of The Daily Wire, is warning Republicans not to get too cocky. On his March 28 podcast, Shapiro noted that victorious parties often think they’ve permanently realigned politics, pointing to Republicans after George W. Bush won reelection in 2004, and Democrats after Barack Obama’s decisive reelection eight years later. Now, he said, “I hear Republicans who seem triumphalist about the idea that Democrats can never win again, that Democrats will never take power again, that all the trends are against them. … However, politics changes quickly, things happen, and there are warning signs on the horizon.”

A week later, Trump announced his tariffs, and the major stock market indexes fell as much as 10 percent in two days.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.