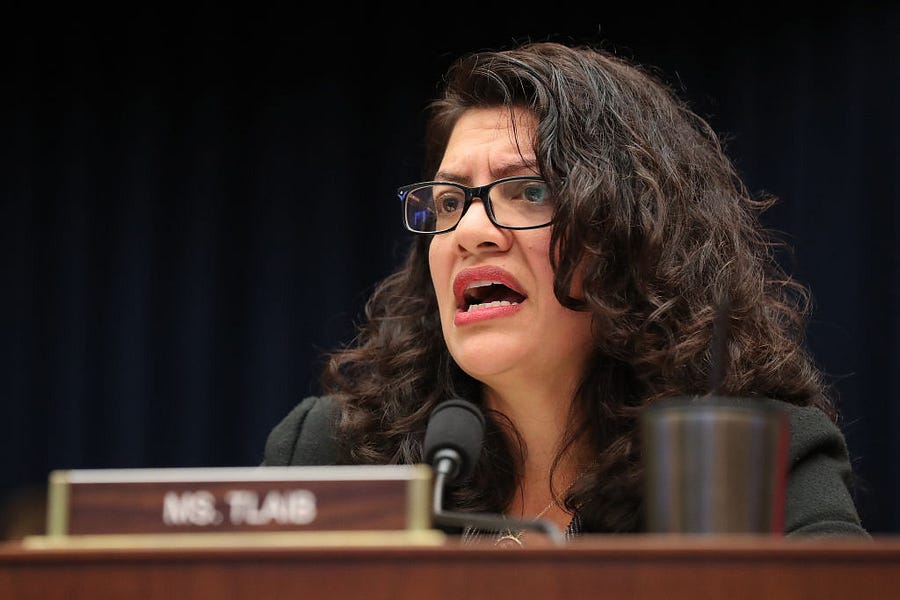

Among the most important tools in a politician’s toolbox is the ability to dodge an unflattering question. In an interview segment released Monday, Rep. Rashida Tlaib (D-Michigan) offered a textbook case study in how not to do it.

In the interview, Axios’s Jonathan Swan pressed Tlaib on the BREATHE Act, a bill authored by the social-justice coalition Movement for Black Lives and backed by Tlaib and fellow “Squad” member Ayanna Pressley, among others. Swan noted that the proposal would empty federal prisons—home to about 12 percent of prisoners nationwide—within a decade of passage.

Tlaib denied this (“Everyone’s like, ‘Oh my God, we’re going to just release everybody’”), but the bill’s text clearly instructs the federal Bureau of Prisons to cut the prison population in half within five years and attain “complete decarceration” within 10, in addition to “physically closing all federal prisons.” Pressed further, Tlaib hemmed and hawed, insisting that the real problem was providing mental health and drug addiction care, while never quite coming out against freeing thousands of drug traffickers, weapons offenders, and other serious criminals in federal detention.

Tlaib’s awkward performance has prompted (rightful) ridicule on social media. But her obvious discomfort with a bill she endorsed only a year ago reveals an important shift in the political winds. As violent crime has soared, public support for radical proposals like the BREATHE Act has ebbed. That’s left progressive Democrats in an awkward position, unwilling to back down from their beliefs, but aware that they erred in showing their hand so quickly.

What is the BREATHE Act, Anyway?

In the aftermath of George Floyd’s death, “police reform” jumped to the top of legislative agendas, and congressional Democrats and Republicans each quickly floated bills. But the then-surging movement to “defund the police,” which explicitly framed itself in opposition to “reform,” insisted that small changes would do little to address the harms of an institution they believed to be racist and destructive beyond repair. This attitude, prevalent in the Democratic party’s progressive wing, halted legislative negotiations, still unresolved as of the time of writing.

The activists who helped quash the Democrats’ more moderate bill ended up floating a proposal of their own: the BREATHE Act, a sort of wish-list for the defund agenda.

The bill, draft text of which was released in September 2020, puts the basic idea of “defunding the police” into legislative language: move money out of law enforcement budgets into less punitive alternatives. In addition to mandating the closure of all federal prisons, the BREATHE Act would end federal funding for policing, slash the defense budget, dramatically curb federal pretrial detention, end mandatory minimums and “three strikes” sentencing laws, and effectively abolish ICE—among other changes. It would in turn expand funding for “preventive, non-carceral, non-punitive” approaches to managing public safety, from “violence interrupters” to increasing transfer spending on housing, health, education, and the like. It also makes policy changes at best tenuously linked to criminal justice, e.g. repealing the Hyde Amendment or implementing a “baby bonds” program.

In essence, the BREATHE Act is the legislative implementation of one long-standing progressive theory of crime. Crime is a product of deprivation, this account goes, ergo criminal justice policy should focus on alleviating deprivation. This includes rejecting punitivity, both because criminal offenders are not really responsible for their actions (because they acted out of deprivation), and because policing and prisons in turn contribute to deprivation even as they alleviate crime.

There are more problems with this model than can be spelled out in limited space. But suffice to say: Even if deprivation is the sole cause of criminal offending (a highly dubious claim), a criminal-justice agenda that says we must abolish it to address crime asks the impossible of government. This is particularly so when it entails giving up on policing, one of the most effective crime fighting tools. The costs of such an approach would end up being borne most by those disproportionately at risk of criminal victimization—the poor, black, and otherwise disadvantaged for whom Tlaib and her colleagues claim to speak.

What BREATHE Really Meant

The BREATHE Act was always a messaging bill, an anchor congressional progressives could use in their negotiations over what “reform” would look like. But its original introduction, and the political liability Tlaib’s interview suggests it now is, tells us something about the shifting politics of criminal justice reform.

Firstly, BREATHE encapsulated progressives’ true priorities. The “criminal justice reform” movement had long been a tepidly bipartisan affair—consider, e.g., the timidity of the Trump-backed FIRST STEP Act, which mostly trimmed around the edges of the federal sentencing regime. But the summer of 2020 seemed to, just for a moment, offer the possibility of truly revolutionary change to the criminal justice system. That prompted progressives to go big, certain that the political energy of the “defund” movement would at least wring substantial concessions out of Democratic leadership.

Of course, this turned out not to be true: Defund was and remains radically unpopular, and the 2020 surge in homicide—which I and others have linked to nationwide anti-police protests—has made public safety a winning issue for Republicans. This explains, perhaps, Tlaib’s flustered appearance: She, like other progressives, still believe in the ideas behind BREATHE, but they know promising to close federal prisons is not the winning proposal they thought it would be.

There’s certainly a way forward on police reform—evidence suggests that we can curb misconduct and unnecessary use of force while preserving effective policing. But getting there means moving past the radicalism of last summer. In that sense, Tlaib’s discomfort is a positive sign, an indication that even she knows Americans want sensible reform that enhances, rather than diminishes, public safety.

Charles Fain Lehman is a fellow at the Manhattan Institute and a contributing editor to City Journal.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.