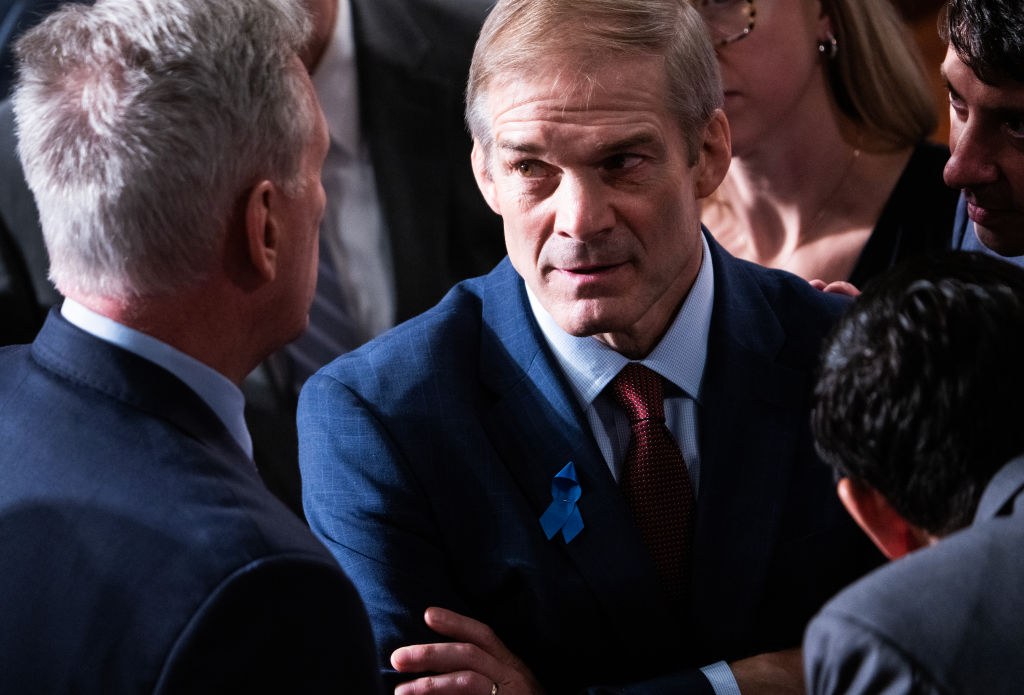

Audible gasps rang out in the House chamber Tuesday when Rep. Kay Granger of Texas cast her vote for speaker. The formidable, 80-year-old Republican with more than a quarter century of experience on Capitol Hill voted not for Rep. Jim Jordan like the vast majority of her GOP colleagues, but for the man Jordan’s allies had helped shunt aside: Majority Leader Steve Scalise.

Granger’s decision wasn’t a surprise because it was the decisive vote for the House GOP’s slim majority; she was only one of 20 Republicans on Tuesday—and 22 on Wednesday—to vote against Jordan and deny him the speakership. Her opposition to Jordan shocked her colleagues because of what it represented. As chair of the powerful Appropriations Committee, Granger might have been expected to align herself with a future speaker, who has considerable influence over both the committee process and the business brought to the House floor for votes. That she didn’t was a strong statement of no confidence in the party’s designee from a House veteran.

Shortly after Tuesday’s vote, The Dispatch asked Granger what Jordan would have to do to earn her support. “I’m not doing that,” the congresswoman replied, dismissively waving her hand before walking away.

The question might have been better posed to Jordan: What was he doing in order to get this critical leader in the conference on his side? A statement from Granger on Wednesday following Republicans’ second failed attempt to elect a new speaker hints at how Jordan and his allies have been approaching institutionalist holdouts like her.

“This was a vote of conscience and I stayed true to my principles,” Granger said. “Intimidation and threats will not change my position.” Her comments echoed statements from other Jordan detractors who suggested Jordan’s supporters had tried—and failed—to bully them into supporting the pugnacious co-founder of the House Freedom Caucus. The intimidation campaign has also made it to the airwaves, with several conservative media allies of Jordan—notably Fox News host Sean Hannity—using their platforms to go after the “sensitive little snowflakes” in the House not willing to get on board. It’s a tactic that has worked for certain GOP leaders in the past.

Jordan sought to turn the temperature down on Wednesday evening—after GOP Rep. Mariannette Miller-Meeks of Iowa claimed she had received “credible death threats” for withdrawing her support of the Ohio Republican—by tweeting a condemnation of any and all threats against his colleagues, which he described as “abhorrent.” Russell Dye, a spokesman for Jordan, echoed that sentiment in a statement provided to The Dispatch. “Mr. Jordan hasn’t made any deals, made any threats, or encouraged any attacks on any members voting against him,” Dye said. “Neither has our team. He has been clear that we must stop the attacks and come together as a Conference.”

But other Republicans who have opposed Jordan have a different recollection of the past few weeks. And according to Rep. Carlos Giménez of Florida, the pro-Jordan push may have backfired. “I don’t appreciate the pressure tactic,” Giménez told The Dispatch. “Because you know what? You follow leaders. You don’t get pressured.”

Rep. Don Bacon of Nebraska has suggested Jordan allies in and out of Congress have been doing the dirty work for him. “Jim’s been nice, one-on-one, but his broader team has been playing hardball,” Bacon told Politico, which also reported that Bacon’s wife had received “multiple anonymous phone calls and text messages” urging her husband to support Jordan.

To the extent that Republicans have been able to unify since the election of Donald Trump in 2016, that consensus has largely maintained through fear: fear of going against the most popular leader within the party, fear of inviting a torrent of negative right-wing media attention, fear of crossing the GOP base, and, ultimately, fear of a primary challenge. But Jordan’s failure to secure the speakership thus far demonstrates the limits of fear-based Trumpian tactics—and the remaining value of the sort of old-fashioned personal politics that still drive much of the actual legislative work of Congress.

It’s a lesson that Rep. Kevin McCarthy, the recently ousted speaker, knows all too well. A back-slapping people pleaser, McCarthy built his support within the Republican conference by establishing personal relationships with members that often began with him recruiting them to run and supporting them with his fundraising machine. He continued to cultivate friendships by remembering small, personal details of his members’ lives like kids’ birthdays or pets’ names—attracting flies with honey, not vinegar.

The problem with McCarthy’s strategy was that he ended up drowning in all the honey. His ascension to the speakership in January came after more than a dozen failed votes on the House floor, with right-wing holdouts seizing their opportunity to extract more concessions from their once and future leader. In the end, this willingness to meet all these members’ various demands was McCarthy’s undoing. His ouster earlier this month was only possible because he had agreed to a rule change that made it easier for disgruntled lawmakers to trigger a vote on whether to give him the boot.

Ten months later, Jordan appears to be deploying both honey and vinegar in his own quest for the speakership. Stories abound from Republican members about Jordan’s personal friendliness and affability, and he was and still is loyal to McCarthy.

Yet much of his tenure in the House has been defined by his strident opposition to Republican leadership efforts to bring order to divided government and being a media-savvy brawler for conservative populists. He fiercely defended Trump on the House Intelligence Committee during the president’s first impeachment inquiry, and from his perch as the House Judiciary Committee chairman he has been the leader of Republicans’ efforts to investigate and impeach President Joe Biden. He was among the House conservatives who supported the “defund Obamacare” effort in 2013 that shut down the government—and resisted efforts to reopen it. He continued to lead opposition against additional budget resolutions as the Republicans in Congress and Barack Obama found themselves at impasse after impasse on spending.

And as a co-founder of the intractable House Freedom Caucus (HFC), Jordan was, in some ways, the inspiration for the small but dedicated anti-McCarthy crew that put Republicans in their current predicament. The HFC, after all, agitated enough to convince then-Speaker John Boehner to resign from Congress rather than try to pass another funding resolution that Jordan and his ilk would viciously oppose.

His effort to cajole the holdouts this week seems not to have overcome the sense among these members—mostly institutionalists who prefer regular order to any particular ideology—that supporting Jordan means rewarding those who got the conference here in the first place. His allies’ tactics, including several pro-Jordan members refusing as a bloc to commit to supporting Steve Scalise after the majority leader won the conference’s support for speaker last week, have only reinforced this sense.

Heading into Tuesday’s vote, Rep. Mario Diaz-Balart of Florida indicated he would not support Jordan but repeatedly told reporters that he is always open to negotiation. After the roll-call vote resulted in no speaker, Diaz-Balart sat in a corner of the House chamber with Jordan himself, the two smiling and chatting amicably. If Jordan was going to convince one of his hardest “no’s” to get on board, this seemed to be the time and place to do so.

As he emerged from the chamber, Diaz-Balart refused to divulge what he and Jordan spoke about. But were he and the would-be speaker at least negotiating? “No,” Diaz-Balart said firmly. “The millisecond when anybody tries to intimidate me is the moment that I no longer have the flexibility, because I will not be pressured or intimidated.”

The next day, Diaz-Balart and 21 of his Republican colleagues voted against Jordan, and the House, at least for another day, remained without a speaker.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.