Tim Scott was frustrated.

Just days earlier, Senate Democrats had blocked—in his mind, for purely political reasons—the police reform legislation he had spent the better part of his career thinking about, and the better part of June scrambling to put into legalese. It would have been a legacy-defining moment—not that he cares much about such things—and provided Republicans another message with which to make inroads into the black community before November.

Joining CNN’s State of the Union to discuss the JUSTICE Act’s failure, he could barely muster a perfunctory “good to be back with you” before Jake Tapper opened the conversation. “President Trump just retweeted a video this morning featuring one of his apparent supporters shouting, ‘white power.’ … What’s your reaction to the president retweeting that?”

Scott’s characteristic smile was gone, and any remnant of it had drained from his eyes. “Well, there’s no question he should not have retweeted it,” he said matter-of-factly. “And he should just take it down.”

‘I am a Christian, who is a conservative, and you may have noticed that I’m black.’

Scott—the lone black Republican in the Senate, and the only black person in either party to ever serve in both chambers of Congress—did not set out in the mid-1990s to have a political career defined by his race. Former Rep. Trey Gowdy—Scott’s best friend in Washington—shared with me the go-to introduction South Carolina’s junior senator has come to deploy: “I am a Christian, who is a conservative, and you may have noticed that I’m black.” But like most Americans with Tim’s complexion, that last part of his identity has often drowned out the other two—whether he wants it to or not.

Scott cemented his elevated status in Washington before he was even sworn into the House of Representatives in 2011; the stories about his primary victory in South Carolina over the son of longtime segregationist Sen. Strom Thurmond practically wrote themselves. “It didn’t take long for me to become aware of the media’s high interest in the two new black Republicans, Allen West and me,” Scott wrote in his 2018 book—Unified—which he co-authored with Gowdy. “The Republican House leadership encouraged us to be as visible as we felt comfortable with on the issues that mattered to each of us. It was an incredible opportunity for them to have two African American Republican members of Congress.”

Most up-and-coming politicians would have relished the attention. West certainly did. But not Tim Scott. “I quickly decided that I did not want to become the guy who represents ‘the conservative black perspective’ on every issue,” he wrote. He declined to join the Congressional Black Caucus, and he turned down repeat solicitations to run for House freshman class president—a race many of his peers thought he’d win unopposed if he’d entered. He didn’t seek high-profile committee placements either, beginning his career on the Small Business and Transportation committees.* “I think he was understandably resistant to simply be defined as someone that you come talk to when there’s a racial issue,” Gowdy told me.

West lost his re-election bid in 2012 to Democrat Patrick Murphy. Scott easily won a second term, and, one month later, South Carolina Gov. Nikki Haley appointed him to the Senate to replace the retiring Jim DeMint. He won the right to finish out DeMint’s term in a 2014 special election, and he secured a full term of his own two years later. His 23.7-point margin over Democrat Thomas Dixon in 2016 was the narrowest general election victory of his national political career.

But in between those latter two campaigns, three months in 2015 changed Scott’s life.

Early in the morning of April 4, a white police officer named Michael Slager shot and killed an unarmed black man, Walter Scott, after a routine traffic stop. Slager lied about the encounter, telling a dispatcher Scott had stolen his Taser. A bystander’s video recording made clear that wasn’t the case; Slager was not in any danger when he pulled the trigger eight times while Scott, 50, was running away.

Tim and Walter Scott shared no relation. But they might as well have. The murder took place in the senator’s hometown of North Charleston—the city where his single mother, Frances Scott, worked 16-hour days changing bedpans in the hospital; where the lights and the phone in his home wouldn’t always turn on when he needed them; where he failed high school Spanish, English, and civics; where a car wreck ended his dreams of playing Division I football—and Scott was more heartbroken by Walter’s killing than he was surprised.

“The horrific video that came to light yesterday is deeply troubling,” he said in a statement at the time. “It is clear the killing of Walter Scott was unnecessary and avoidable.”

Less than three months later, a 21-year-old white supremacist—Dylann Roof—entered a Bible study at Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church—Mother Emanuel—and, in the hopes of sparking a race war, gunned down eight black congregants and the church’s senior pastor, Clementa Pinckney.

Pinckney was a friend of Scott’s. “Clementa was one of the first to call me Senator,” Scott recalled in his book. “I remembered that day, that conversation, and our plans to work together on issues near and dear to both our hearts. Poverty. Education. Helping the community. We had so many ideas for the ways we would serve South Carolina to improve the lives of the people. We knew if we could show people that we were crossing party lines to work together, as a Democrat and a Republican, the community would be willing to work together too. … We had big plans.”

‘He definitely processed a lot of it as a calling.’

“I think that’s accurate.”

I had just asked Scott if he agreed with my perspective as an outsider: That he has grown more comfortable over the past ten years speaking up and pushing his party on race.

“My goal has always been to build credibility before I offer solutions,” he continued. “That means listening and letting people know you aren’t just waiting to talk, but you’re actually listening to what they have to say. And as time has evolved, what I’ve come to conclude is that there are some issues that haven’t been dealt with and they need to be dealt with.”

Friends say this evolution began in that fateful spring of 2015. “It was a combination of Mr. Scott’s shooting and the massacre at Mother Emanuel Church,” Gowdy said. “Far more than from a political perspective, from a spiritual perspective and a life perspective, he felt an obligation to speak.”

“In 2015, as I was getting to know him, some of those events in South Carolina were pretty important, formative influences on him,” Sen. Ben Sasse remembered. “Figuring out how he’d respond to it in public. And he definitely processed a lot of it as a calling.”

On June 22 of that year, Scott appealed for the Confederate battle flag—with which Roof had been repeatedly photographed—to be removed from the South Carolina Statehouse. But his statement walked a narrow tightrope many of his colleagues from the North could ignore entirely. “I do not believe the vast majority of folks who support the flag have hate in their hearts. Their heritage is a part of our state’s history, and we should not ignore that,” he said. “However, for so many others in our state, the flag represents pain and oppression. Because of that, as a life-long South Carolinian, as someone who loves this state and will never call anywhere else home, I believe it is time for the flag to come down.”

A little over a year later, racial tensions returned to the fore. Two separate videos of black men—Alton Sterling in Louisiana and Philando Castile in Minnesota—being killed by law enforcement officers surfaced within days of each other, and a black man in Dallas gunned down five police in retaliation.

On July 13, 2016, Scott did something on the Senate floor he never could have imagined as a House freshman just a few years earlier: He shared his reality.

“In the course of one year, I’ve been stopped seven times by law enforcement officers. Not four. Not five. Not six. But seven times. In one year. As an elected official.” The pauses between his words felt longer than they were. “I recall walking into an office building just last year after being here for five years on the Capitol, and the officer looked at me—a little attitude—and said, ‘The pin, I know. You, I don’t. Show me your ID.’ … Later that evening I received a phone call from [the officer’s] supervisor apologizing for the behavior. Mr. President, that is at least the third phone call that I’ve received from a supervisor or the chief of police since I’ve been in the Senate.”

“There is absolutely nothing more frustrating, more damaging to your soul than when you know you’re following the rules and being treated like you are not,” Scott said. He pleaded with his colleagues: “Recognize that just because you do not feel the pain, the anguish of another, does not mean that it does not exist.”

In a profession epitomized by long-windedness, Scott is not known for being particularly loquacious. “He’s the worst self-promoter in the world,” Gowdy maintained. “He turns down more television—I mean, you literally have to beg him.”

But Scott’s Christian faith—at one point he thought about going to seminary—called him to raise his voice on this issue. “He believes that he has been given an opportunity,” Gowdy disclosed, “and that he should seize that opportunity, even if it is not necessarily what he most wants to talk about. I think he’d love to live in a country where we were not having this conversation.”

“Look, he was in politics how many years before I—as the person who’s around him the most—ever learned that he was stopped seven times in one year as a public official,” he continued. “He doesn’t lead with that. I had to know him for three years before he told me about racial epithets that were hurled against him when he was in college.”

You might not expect someone so soft-spoken to drive around with a “United States Senate” vanity license plate adorned with just the number ‘2.’ (Lindsey Graham, South Carolina’s senior senator, is presumably number ‘1.’) When Gowdy first saw the plates—which Scott has since switched out—he remembered giving his buddy crap. “‘This is the dumbest thing I’ve ever seen in my life. Every time you speed or change lanes without using your signal, they’re going to call talk radio. Why in the world would you do this?’” he joked with him. He said Scott laughed, but not a lot. “I want the officer to know that I’m not a threat to him,” he responded. “So he won’t be a threat to me.”

The pain associated with Scott’s blackness was real. Yet he was reluctant to acknowledge it—at least publicly—for years. What changed?

He came to the conclusion that his keeping quiet was a tacit endorsement of the status quo.

“Our silence is actually an answer,” he explained to me. “It’s not the answer that we are trying to convey, but it’s the answer that’s been received. Our silence has been deafening.”

But just as silence can be deafening, when deployed strategically, it can also speak volumes. I asked Scott for examples of times he had to bite his tongue—things insurance salesman Tim Scott could have articulated that Sen. Tim Scott couldn’t.

“In direct contradiction to what I just said,” he responded with a laugh, “sometimes the best thing you can do is let silence be golden. … If someone else is saying it, I don’t need to say it. If no one else is saying it, I probably need to speak up.”

“It’s a balancing act, right?”

‘There are days, I am sure, he feels like a man without a home.’

Being a black Republican is undoubtedly a balancing act, and it might just be the most precarious one in modern politics.

“I just can’t imagine the pressure [Tim Scott] must be under … as the only African American Republican,” Democratic Rep. Karen Bass, chairwoman of the Congressional Black Caucus (CBC), told the Associated Press. “That he has to sit there with those senators and go through his experiences and hope that they have some measure of empathy.”

Bass—who was elected to Congress the same year as Scott—told me she’s never talked to him about why he didn’t join the CBC, but made clear she harbors no ill will over his decision. “That’s his choice,” she said in an interview. “He knows that the Congressional Black Caucus is overwhelmingly Democratic, and maybe he felt uncomfortable.”

“We all respected Tim when he was in the House, we were happy when he was appointed to the Senate,” she continued. “We thought that was a huge deal.”

Scott is beloved by his colleagues in Congress’ upper chamber. “I don’t think Tim has an enemy or a rival, or someone who wants to hurt him, in the Senate,” Sen. Marco Rubio said. “He’s liked, but more than anything else, he’s respected by members of both parties, which is a unique place to be and a hard thing to achieve.”

“I think a great deal of him,” Sen. Mitt Romney added over the phone. “I judge him to be a man driven more by principle than by politics. … I think of him as being one of the most effective advocates for what he believes in the caucus.”

“So much of D.C. is defined by political identity or by status,” Sasse said. “And Tim’s just not like that. … American politics, in my view, would be a lot healthier if there were a lot more people like Tim Scott.”

As Rubio mentioned, these sentiments don’t stop at the partisan dividing line, either. “We have come to be friends through time spent together in South Carolina on a civil rights pilgrimage and at the weekly Senate Prayer Breakfast,” Democratic Sen. Chris Coons wrote. “He is a conservative through and through, and while we often disagree on policy, he is always focused on doing what he believes is best for South Carolina and our country and working across the aisle to get things done.”

These bipartisan relationships were tested during the latest back-and-forth over police reform. The Republican proposal—which Majority Leader Mitch McConnell tapped Scott to lead—would have required local police departments to collect data on any use of force resulting in death or serious injury, withheld federal funding from states and law enforcement agencies that didn’t ban chokeholds in most instances, provided money to state and local governments for body cameras, and made lynching a federal crime. The House Democrats’ plan would have done much of the same, but outright banned chokeholds and no-knock warrants at the federal level and reformed qualified immunity—a “non-starter” for the White House—as well.

Over these divergences, Speaker Nancy Pelosi accused Republicans of “trying to get away with … the murder of George Floyd,” and Sen. Dick Durbin called Scott’s legislation a “token, half-hearted approach”—a comment for which he later apologized. But most Democrats criticizing Scott’s JUSTICE Act in recent weeks have gone out of their way to praise its author, a courtesy afforded less and less in today’s tribal era.

“I disagree with parts of the legislation, but I don’t doubt his motives,” Bass said. “I think he wrote the best bill that he felt he could write.”

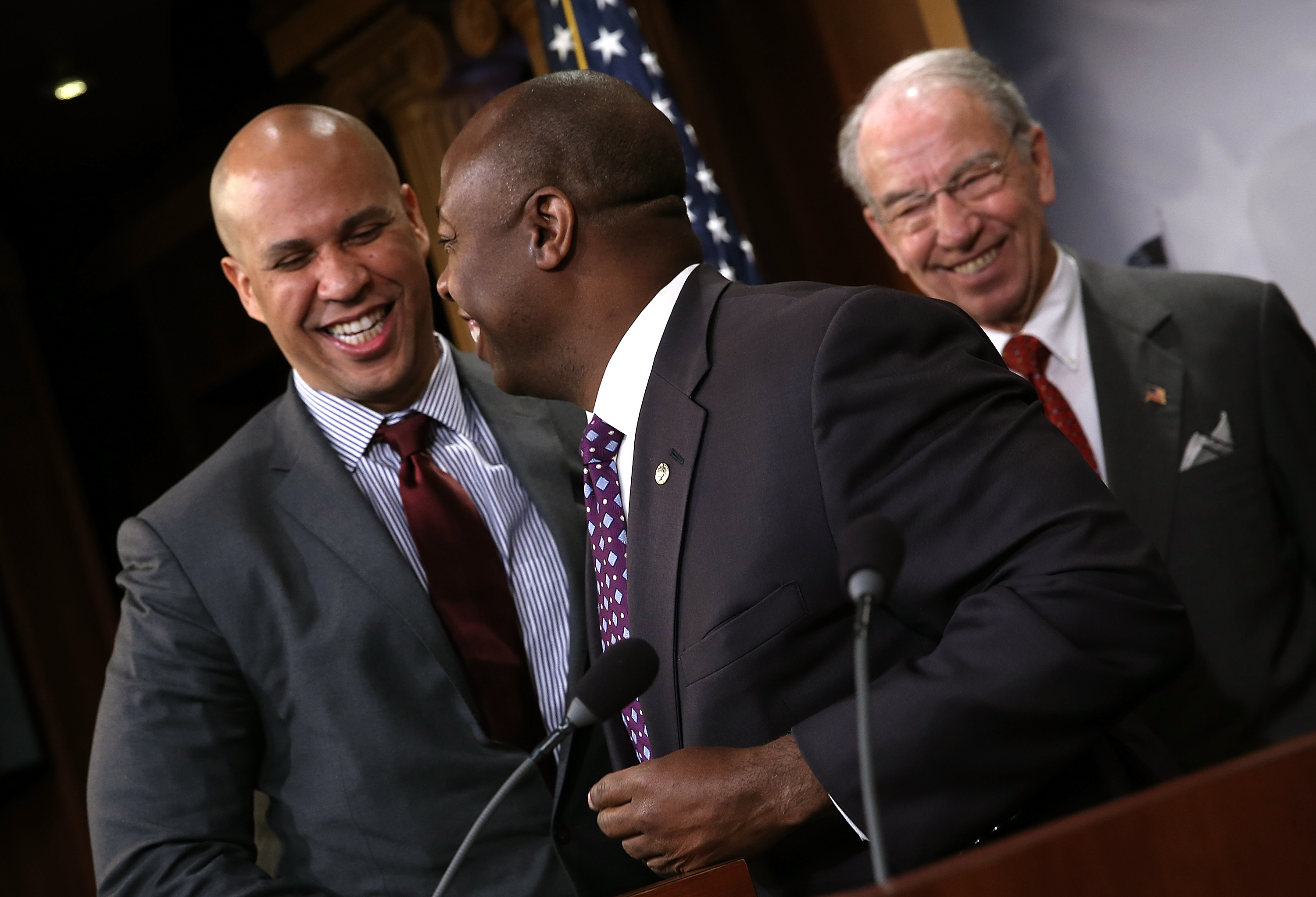

“I honor him, I love him,” added Sen. Cory Booker—one of only two black Democrats in the Senate. “We are far apart right now, far apart on many issues. But he’s always been somebody that I’ve been able to sit down and have conversations, and that’s the beginning of hope for me. … I am confident that he is sincere in his earnestness to stop black lives from being killed.”

Scott’s popularity holds true among voters, too. He hasn’t maintained his extraordinary +40 net approval from—per Morning Consult polling—early 2017, but his +24 rating in today’s hyper-polarized environment is the envy of all but a handful of senators. “He’s the most popular person in South Carolina by far,” said Gowdy, who is also from South Carolina. But Scott is not complacent. “There was a poll run in another race. And I think among Republican primary voters, Tim had an approval rating of 93. And I said, ‘I guarantee you, Tim is out there trying to find that 7 percent to figure out what he can do to make things right.’ I mean, Lindsey [Graham, South Carolina’s senior senator] would be saying, ‘Look at all the room I have to offend people!’”

So if his coworkers love him, and his constituents love him, what’s this balancing act Scott speaks of?

To Scott, his blackness and his partisan affiliation makes perfect sense: He’s lived the American dream, rising from poverty to build a series of successful businesses. He’s a devout Christian committed to the preservation of religious liberty. But to interlopers projecting their own experiences and beliefs onto him, two of his three core identities are in direct contradiction with one another. Leaning too hard into one elicits accusations of being traitorous to the other.

Look at Twitter. “Tim Scott was the house negro who run to the master to tell that other slaves were planning to run away. Slavery might be over but Tim Scott’s mind is still in chains and shackles,” one reply to Scott says. “I need you to STOP talking about Charlottesville like our President said something racist when you and I BOTH KNOW HE DIDN’T. STOP SPREADING THAT SHIT. IT’S A LIE and you KNOW it,” reads another.

Scott himself tried to provide a window into his world on the Senate floor after Jeff Sessions’ attorney general confirmation battle in February 2017. “I go on to read from folks who wanted to share their opinions about my endorsing Jeff Sessions,” he read. “‘You are a disgrace to the black race.’ Anthony Burnum at @burmanr says, ‘You are an Uncle Tom, Scott. You’re for Sessions. How does a black man turn on his own?’” Scott took off his glasses. “I left out all the ones that used the N-word. Just felt like that would not be appropriate.”

“If you sign up to be a black conservative, the chances are very high you will be attacked. It comes with the territory.”

A lifetime of vitriol has certainly thickened Scott’s skin. But the result is a heartbreaking numbness. “I felt this way in high school,” he acknowledged. “I kind of liked everybody and didn’t want to be pigeonholed. I was called everything from Oreo to the N-word. Which was fascinating back then. It’s not quite as fascinating now because I’ve had it so often. It’s”—he paused—“you know, you shrug your shoulders at most of it.”

And the slights do cut both ways.

“Tim attended several vigils and memorials” in the wake of the mass murder at Mother Emanuel, Gowdy wrote in his book. “At some of those gatherings, even though he was the highest-ranking elected official in attendance, even though he lives in Charleston, and even though he had a family connection within Emanuel, he was not asked to speak. Why?”

Gowdy also remembered calling Scott in the fall of 2017 to ask how a meeting with a South Carolina GOP women’s group went. “Honestly, Trey, it didn’t go great,” Scott replied. “They don’t think I support the president enough.”

“This is right after Charlottesville,” Gowdy made clear. “It’s an impossible situation. The base doesn’t want you saying anything, your critics want you publicly excoriating him. How do you find that—for him—spiritual middle ground, where you do correct and reprove someone, but you do it in a constructive way? There’s just not a huge appetite for that politics.”

“There are days, I am sure, he feels like a man without a home.”

A sliding doors moment in the Palmetto State.

If it weren’t for a handful of Democrats running for the Charleston County Council 25 years ago, Scott’s career could have been a whole lot more conventional—and a whole lot less impactful. He was a successful businessman in Charleston—he owned his own Allstate agency—when he began thinking about a career in public service. The local Democratic Party told him to “get in line.” The Republican Party? “We’d love to see you run.”

“There’s no doubt that number one, philosophically, I’m a Republican,” Scott told me. “I was then, I am now. But everybody that I knew that was African American was a Democrat. So my natural inclination was at least to give it a shot.”

Does he wish more black politicians made the choice he did, forever losing the ‘lone black Republican in the Senate’ tagline included in every story about him? “Misery loves company.” I could hear his smile through the phone. “I welcome all to come and have some of this! That would be awesome!”

But one quarter-century and a national political career later, he’s happy with his decision. “Sometimes you gotta thank God when they say no,” he said with a laugh. “Had I been a Democrat—even if I was lucky enough to somehow convince South Carolina voters to vote for me as a Democrat—then my relationship with the White House would have been completely different now. … I find myself having access to the president when I need it the most, and when I want it usually.”

To varying degrees, Republican elected officials at all levels of government have chosen to make their peace with Donald Trump’s presidency. The real estate tycoon wasn’t Scott’s first choice in 2016—that was Marco Rubio—and he likely wasn’t his second, third, fourth, fifth, or sixth. But in the years since Trump remade the GOP in his own image, few have gotten more out of the deal than the junior senator from South Carolina.

“I believe that Charlottesville is the reason we have Opportunity Zones,” Scott divulged, referencing the language he got included in the GOP’s tax reform legislation that incentivizes long-term investment into distressed communities. “The president and I had a difficult and hard conversation about why I thought he had compromised his moral authority.”

That conversation took place a few weeks after Trump equivocated on where the blame lay for the violent and deadly clashes in Virginia between white supremacists and counterprotesters. “His question was, how can I help those I’ve offended?” Scott said he was shocked. “I didn’t know Opportunity Zones was going to come out my mouth, because I hadn’t come in there assuming that he was going to say something that required a response.”

“It was the first thing that I thought would actually have a meaningful impact if I was still a 7-year-old kid living in poverty in a single parent house, unable to get to where opportunity starts,” Scott recalled. “And the next day, he was out there saying that it was a good idea for us to bring more money back into those communities.”

Scott doesn’t speak to Trump as often as some of his Senate Republican colleagues; their relationship is more transactional than it is close. “My guess is the president calls Tim more than Tim calls the President,” Gowdy said. But their mutual understanding has benefited them both: Scott has championed into law a laundry list of policy priorities previously unthinkable under a Republican president and Senate majority; Trump will enter his re-election bid with a more credible case to make to the black community—albeit one he has fumbled away in recent months with his inflammatory rhetoric.

In the three years since Charlottesville, Scott has fought for—on his own or as part of a coalition—criminal justice reform, permanent funding for historically black colleges and universities, legislation aimed at fighting sickle cell anemia, and a provision in the most recent farm bill that assists farmers—usually black farmers—operating on heirs’ property. The Senate passed—and Trump signed—each of these measures into law.

Would any of those pushes have crossed the finish line without Scott in the Senate? I told Gowdy his friend was too humble to answer my question. “Well I’m not,” he shot back. “The answer is no.”

Rubio agreed. “The Opportunity Zones are something that would not have happened without him.” But he wanted to make clear that Scott’s legislative contributions extend far beyond what pundits call racial issues. “He was a central figure in helping us get the Child Tax Credit. If it wasn’t for Tim Scott getting involved and helping us push that through, I’m not sure we would have had some of the changes that were made in our direction. … He was a big part of our focus on small business and what we were able to do on PPP.”

And as a loyal Republican, Scott has been able to pick his spots and push back against the party when he feels he needs to. Rep. Bass referenced his torpedoing the nominations of “some pretty awful judges that were proposed by the administration.” Ryan Bounds and Thomas Farr were chosen for the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals and District Court for the Eastern District of North Carolina, respectively, but each had a less-than-satisfactory track record on race. Scott cast the deciding vote to block both of their confirmations. “If he was only caucusing with the Democrats, I don’t know how he would have credibility within his own party to oppose what the party was doing,” Bass said.

Scott explained his approach to negotiations with the White House and his fellow senators. “If you have rapport, and then on top of rapport, you layer credibility, you actually get permission … to start solving problems together.”

“I try to work with my colleagues—both Republicans and Democrats—because we all know that in the Senate, 51 is not a majority, 60 is,” he added. “I try to design [legislation] in a way that I’m aware that this will speak to their priorities, their objectives. And if I can get enough information from people on what their priorities are, my legislation gets done. And so who cares who gets the credit, right? I get the win for the people that I’m representing.”

That last line sounds innocuous enough—but in Washington, it’s not. Everyone cares who gets the credit. And in a Senate Republican Conference where pretty much all members under the age of 55 look in the mirror and see a future president, Scott’s lack of ego makes him an anomaly.

Sasse revealed the dynamics of the GOP’s police reform working group over the past few weeks. “Tim has worked the hardest,” he said. But Scott also made a concerted effort to share the spotlight. “Somebody may have thrown in one thought, and Tim and his team did the yeoman’s work of making it into actual legislative text and wrestling it through different complicated debates inside our conference. That’s who Tim is. He’s a really, really hard worker who’s remarkably low ego, which is why he’s so pleasant and it’d be so great if we had so many more people like him.”

Romney concurred. “He works hard. As you know, there are some senators who work harder than others. He works hard on the issues that he cares most about.”

“We’re in a line of work that rewards ambition,” Gowdy conceded. “You can’t say that you’re in politics and have no ambition. But [Scott] is the least overtly ambitious person I have ever seen in politics.”

“He is too good of a person for the line of work that he is in.” Gowdy’s voice trailed off. “He’s just too good of a person.”

‘Tim has a gift of being able to correct you in a constructive way.’

In a national political moment increasingly defined by strict adherence to one set of orthodoxies or another, Tim Scott has charted another path.

This is not to say he hasn’t at times succumbed to the allures of rank partisanship—he has. Just last week he explained away devastating—and credible—allegations against President Trump in John Bolton’s new book by saying they were never cross-examined: “I do wish that Mr. Bolton would have come into the House under oath and testified,” he said on ABC. But Scott himself voted not to call additional witnesses—including Bolton—to testify during January’s impeachment trial in the Senate.

More than perhaps any other politician in the Trump era, though, Scott has parlayed this partisanship into real-world results. Not Air Force One trips, or Twitter celebrity, or cable news hits—though he’s had to up the frequency of those in recent weeks to sell the JUSTICE Act—but legislation he believes will make a tangible difference in millions of Americans’ lives across the country.

He’s done it by treating the people in his life not as members of broader demographic or political groups—half of whom can be safely disregarded—but as individuals worth listening to, learning from, and engaging with. “It’s easy to hate or demonize a group or a crowd,” he concluded in his book. “But it’s hard to hate a person whom you’ve gotten to know.”

Scott references his own personal failings in spelling out the importance of grace for others. “I’m often reminded that I’m a sinner too, and I fall short in so many ways,” he admitted. “I think it’s been helpful to just remember that most people come to the table with good intentions. We all come to the table with very different experiences. And if I’m willing to hear their experience and understand their position, then instinctively I’ll get to a better conclusion.”

Sasse believes that deep down, what most Americans despise even more than their perceived political opponents are political addicts: “People who can’t shut up thinking that every issue is about politics.”

“Tim is just not like that,” he said. “Unlike most people who run for office, who therefore obviously have a disproportionate emotional investment in politics, Tim is a normal, healthy person. … One of the things he’s partly always doing is trying to make sure he helps people translate political debates in ways that actually fit back around the dinner table in South Carolina, the way normal people process.”

Scott rejects the concept of systemic racism—“I think when you say something is systemically racist, that you’re saying the nation is racist, so I don’t like that, because I know that we are not”—but having been on the receiving end of “pockets of racism” for 54 years, he’d surely be forgiven if he—as Politico’s Tim Alberta put it in 2018—decided to “unleash a lifetime of exasperation and say what he really thinks.” Air decades of pent-up grievances, speak out after every affront, write off the bigots who’ve hurt him.

But he knows his audience—and how easily he could lose it.

“Tim has always looked for opportunities to bring people along and inform them of some of these challenges,” Rubio said, “without destroying the ability to continue to dialogue with them on it.”

A balancing act.

Scott likes to tell the story of a volunteer on his 2008 campaign for the South Carolina House of Representatives—Pete, an ex-cop—who showed up to a door-knocking event with a 9mm handgun tucked into his waistband and a rebel flag emblazoned on his T-shirt.

Keep in mind: Scott lost a South Carolina state Senate race in 1996 in part because he supported removing the flag from the Capitol grounds. But he didn’t send Pete home, or even ask him to change his clothes. “We were as unlikely a pairing as you could find,” he remembered. “A black guy going door-to-door with a guy wearing a Confederate flag.” Pete—like thousands of others drawn into Tim Scott’s orbit—became a friend.

Gowdy is confident Scott moved that retired police officer’s heart. “Tim has a gift of being able to correct you in a constructive way,” he said. “I can 1,000 percent see him walking around with a man in a Confederate flag shirt. And I can see that man at the end of the day—if he has any awareness at all—saying, ‘You know what, I probably have worn this shirt for the last time.’”

Photographs: Tim Scott at the State of the Union by Drew Angerer/Getty Images; Tim Scott speaking the media by Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images; Nikki Haley, Trey Gowdy, Marco Rubio, and Tim Scott by Win McNamee/Getty Images; Tim Scott with Donald Trump by Alex Wong/Getty Images; Cory Booker and Tim Scott by Win McNamee/Getty Images.

*Clarification, July 1, 2020: Scott was initially put on the House Small Business and Transportation and Infrastructure Committees, but then-Speaker John Boehner moved him to the Rules Committee before Scott served any time on the former two.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.