Americans are about to undergo a dramatic social experiment. For generations, our values and ways of life have shifted leftward—that is, toward a more individualized, permissive, secular, do-your-own-thing direction. Now, members of Donald Trump’s coalition have signaled their intent to use the levers of national government to reverse the cultural momentum. How likely are they to succeed?

Over about three generations, more and more Americans departed from the supposedly traditional ways of life typically associated with the 1950s. Family changed as, for example, Americans married later, if at all, and had fewer children. Women’s roles changed as girls obtained advanced education and mothers went out to work. Sexual license expanded, with more Americans seeing premarital sex and homosexuality as normal. Christian hegemony declined, as did religious affiliation generally. The historical hierarchy of race was shaken, most vividly evident in the rise of black-white marriages. An interesting exception is views on abortion, which have remained pretty constant on average but become severely polarized by party. So widespread and persistent has this progressive shift been that it has fueled a counter-revolutionary culture war, a vigorous defense of “the traditional American way of life” by the political right, with some of the defenders even contemplating using physical force.

All branches of the national government have accommodated the liberalizing shifts: legislating for women in college sports through Title IX, allowing women in combat, and using “Ms.” in official documents, expanding rights for unmarried partners (although filing joint IRS returns still requires marriage), establishing the Martin Luther King Jr. holiday, recognizing same-sex marriage, banning mandated prayer in school, legalizing abortion, recognizing gay activist Harvey Milk and the Kwanzaa holiday on U.S. postage stamps, experimenting with Census questions about assigned sex versus current gender, and largely abandoning censorship of sexual display in the media—all this onslaught of change without even mentioning DEI, pronouns, and land acknowledgements. Numerous states and local governments have been even more proactive. For example, in 2004—years before gay marriage was federally recognized—then-Mayor of San Francisco Gavin Newsom started issuing marriage licenses to gay couples and in 2008 he declared that same sex marriage was coming “whether you like it or not.”

To many social conservatives, the government itself has not just accommodated but has driven these cultural changes. In 2019, Trump’s then-Attorney General Bill Barr gave an address at the University of Notre Dame, decrying what he described as the law “being used … to break down traditional moral values and to establish moral relativism as a new orthodoxy,” including by forcing “religious people and entities to subscribe to practices and policies that are antithetical to their faith,” forcing religious employers to fund contraception, “adopting curriculum that is incompatible with traditional religious principles,” and starving “religious schools of generally-available funds.” Religious conservatives on the Supreme Court also feel that faith in America is under attack and needs a strong defense—better yet, an offense. More recently, last year Donald Trump told religious broadcasters, many of whom wore red “Make America Pray Again” caps, that one of his first acts in 2025 would be to establish a task force to fight “anti-Christian bias.” Said Trump: “If I get in, you’re going to be using that power at a level that you’ve never used before.”

Dismantling DEI and related practices in government, such as celebrating black or women’s history months or discharging transgender soldiers, are the first and easiest moves in the campaign for tradition. But more aggressive actions are presumably coming. Indeed, Project 2025—the policy playbook for Trump 2.0, which Trump at one time rejected, but which many in his administration nonetheless appear to be following—argues that policymakers need “to elevate family authority, formation, and cohesion as their top priority and even use government power, including through the tax code, to restore the American family.” The Project’s main author, Heritage Foundation President Kevin Roberts, declared last fall that “We’ve got at most a generation to arrest [the] decline in birth rates … or we will lose the Republic.” The natalist Institute for Family Studies lauded Transportation Secretary Sean Duffy this February for shifting his department’s spending toward communities with high marriage and birth rates. Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. announced, also in February, that his department will recognize only two sexes. Down the road, we will probably see more vouchers to religious schools, sex education and U.S. history sanitized, child tax credits increased, women’s roles in the military circumscribed, and so on.

Will what looks like a campaign to restore the 1950s work? Who knows? There’s a long-running debate in the commentariat over to what extent culture is downstream of politics. History suggests, however, that explicit governmental efforts to undo the social changes of the late 20th century are unlikely to succeed. Let’s understand why by looking at how a handful of these trends emerged in the first place.

Family formation.

The 1950s were hardly traditional; they were aberrant. In that brief period, Americans married years earlier than they had before or have done since; similarly, they had many more children than in the preceding few decades and would have in the following ones. It was the baby boom. Why the upwell of marrying and procreation then? The best explanation is that the boom resulted from the combination of Americans catching up on forming families that they had put off during the Depression and World War II, improving maternal and infant health, the postwar economic boom (the U.S. economy was the only major one left standing), then multiplied by young people accepting and imitating the newly fashionable norms of early marriage and large families. Government helped, especially by subsidizing single-family homebuying, supporting men’s careers through the G.I. Bill, and making tax breaks for couples. But the long-term trends toward smaller families resumed in the 1960s even as those family-friendly programs remained—and largely still remain—in place.

After the mid-1960s, Americans increasingly delayed marriages as more men—but especially more women—pursued college educations. In 1960, women married, on average, at 20; now it’s around 28. Birth rates, both real and desired, dropped. From 1800 to 1940, the average number of children American women had dwindled from seven to two, in step with much of the western world. After 1940, the fertility rate bounced up, reaching 3.6 in 1960, then afterwards plunging back to around two by 1975 and staying there. Circa 1960, the ideal number of children, Americans told pollsters, was on average a high and then close-to-reality 3.5; by 1980, average ideal was down to 2.5, and it’s stayed there, with a small uptick in the last decade. Other affluent countries have experienced even steeper declines in marriage and birth rates. Some have tried mightily to incentivize—and in China, tried to threaten—their citizens to have more babies, with little to show for their efforts. Not much in the current kit of American governmental tools is likely to boost family size short of an immense expansion of financial, childcare, and housing assistance to parents that would dwarf the New Deal. And maybe not even then if the American ideal remains under three children.

The role of women.

The 1950s also saw the heyday of the “breadwinner” family model: the man out in the dog-eat-dog world bringing home enough money so that his wife could devote herself to making a sheltering home for husband and children. But many Americans quickly abandoned this breadwinner model as women increasingly stayed in school and then started going out to work, helping families attain rapidly rising standards of living. In the boomer generation men were about twice as likely as women to graduate college, but in the latest generations about three women graduate to every two men. Indeed, colleges feel pressed to “affirmatively” admit men. The proportion of mothers who worked while raising young children soared from under 20 percent in the 1950s to about 60 percent in the 1990s, leveling out since. Conversely, the proportion of men who lived the breadwinner role—fully employed with a stay-at-home wife—plunged to a small minority. Together, these were probably the greatest changes of American ways of life in the 20th century.

Deep economic and cultural forces best explain these developments, not federal policies. (Most of the moving of women into paid work, by the way, occurred during the Nixon through Reagan administrations.) Anti-discrimination legislation and affirmative action initiatives may have helped women to move out of the home, but such political action—even recently requiring that employers provide working mothers with breast-pumping time—largely followed the entry of women into more and more kinds of jobs, rather than led to that entry.

Sex and sexuality.

Premarital sex was not invented in the 1960s, but it did become more common and more accepted afterwards. Before the ‘60s, first intercourse and certainly pregnancy typically led to marriage; after the ‘60s, the typical life course for Americans included plural premarital experiences and, often, babies before marriage. The stigma of premarital sex has largely gone. As late as the early 1970s, about half of Americans said that premarital sex was always or almost always wrong; these days, disapproval is at about 20 percent, while almost two in three say it is “not wrong at all.” And then, there’s been the dramatic rise in the acceptance of homosexuality: In early ‘70s, about 75 percent said it was wrong; now about 60 percent say that it is “not wrong at all.” The proportion of Americans describing themselves to a pollster as some version of LGBTQ has also steadily climbed.

Again, it is easier to show that the government went along with these trends—for example, ensuring equal protection for same-sex marriages and promoting safe sex rather than promoting less sex—than to show that government policy itself loosened sex from its associated taboos. Could the federal government curtail premarital sex? Well, it’s tried. Federally financed abstinence-only education programs (more of which were called for in the 2020 Republican platform) largely failed to curb teen sex, studies showed. And it is hard to see how federal action, even perhaps overturning gay marriage, could push homosexuals back into the closet.

Masculinity.

The cringeworthy spectacle of Mark Zuckerberg and his fellow tech bros demonstrating their newfound masculinity in part by kissing Donald Trump’s … ring highlights the “vibe” that American men should be more manly. Over the 20th century, middle-class American men were schooled into a certain amount of “feminization,” turning from male companionship at bars to family time at home, conducting “companionate” marriages that entailed heart-to-heart conversation with their wives, and forgoing some of the emblems of an earlier masculinity, such as hunting. The trend persists into this century—for example, husbands increasingly do more of the household cooking and cleaning. What federal policy had to do with this or what federal policy could do to reverse this trend is also hard to imagine. Could state gun laws, for example, get any more encouraging of “carrying” than they are now?

But the new administration has targeted the issue for at least symbolic action. J.D. Vance has complained that “traditional masculine traits are now actively suppressed from childhood all the way through adulthood” in favor of effeminate “soy boys” (and, Vance has expressed at least some tolerance for low-level domestic violence). Trump proudly displays his scowling New York City mugshot, promotes wrestling and martial arts events, and celebrates cartoonish macho figures like Hulk Hogan. But whether such theater will move, for example, division of authority in the home, is questionable.

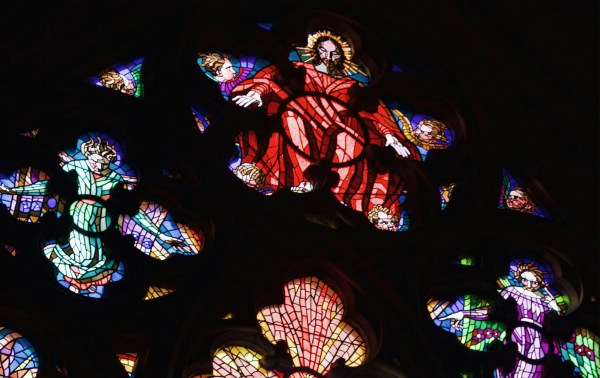

Religion.

Over the last 30 or so years, many fewer Americans declared a religious affiliation, attended church, and, by some measures, believed. Yet, there may be grounds for conservative dreams of a revival—not because of federal initiatives (say, requiring the Ten Commandments in schoolrooms, or bringing back the “blue laws” that closed businesses on Sundays), but because of religious history. America has experienced rises and falls in religious enthusiasm. Church involvement grew tremendously over the course of the 19th century, shrank in the early 20th century, and grew again during those special 1950s. The wheel could turn again. In fact, some have detected that the post-1990 surge in religious estrangement has run its course, perhaps because of COVID or perhaps because of political polarization. Identifying as a Republican leads to identifying as a Christian, so a Republican tide would lift religious, especially evangelical, boats.

Over the years, ministers have often thought that the federal government could advance religiosity. For example, on April 21, 1907, the New York Times reported that President Theodore Roosevelt had been visited by three leading ministers “armed with an arsenal of statistics, all tending to show how the churches were losing their hold on the people, and [asking] that something must be done to revive interest. … The President displayed deep interest and promised to aid the cause in every way possible.” But there is little sign that Teddy made the wheel turn any sooner; a revival followed the post-war baby boom, not any particular government policy.

Today, many argue that the federal government, specifically the courts’ interpretation of the church-state divide, impedes “religious liberty.” They denounce, as Barr did in his Notre Dame speech, pressing businesses to serve gay customers, forcing doctors to accommodate abortion, and preventing spontaneous prayer meetings on school playing fields. Liberating religious people from such strictures may strengthen believers’ commitments (albeit perhaps alienating non- or alternative believers at the same time), but it is hard to see how more liberty would bring back the religious defectors. New York University sociologist Michael Hout and I have argued, with good evidence, that a major reason why so many Americans began rejecting a religious identity (becoming “Nones”) from the 1990s on is that they were put off by the political campaigns the churches engaged in, particularly their attacks on lifestyle liberalization. More political action to press young Americans into church, this time with the feds as allies, may be yet more off-putting.In all these domains, cultural fashions could still turn around. Some social scientists insist that features of our modern economy and society—say, global markets, science, individualism—make the changes in ways of life we’ve seen irreversible, but I am skeptical. Cultural trends are only loosely tied to structural shifts. Example: For all the recent expansion of science and technology, a slightly higher percentage of Americans believe in life after death than did 50 years ago—about 80 percent versus 76 percent—and increasing numbers of Americans believe in ghosts. Being neo-traditional is also one way that the young today can be coolly contrary. Nonetheless, history strongly suggests that were, say, women in droves to embrace their inner housewifery, hospital nurseries to spill over with babies, men to again come home with venison rather than sushi, premarital chastity to become hip, churches to need standing-room only balconies, and drag queens and their fans to disappear from the public square, it would not be because of the federal government—even Trump’s.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.