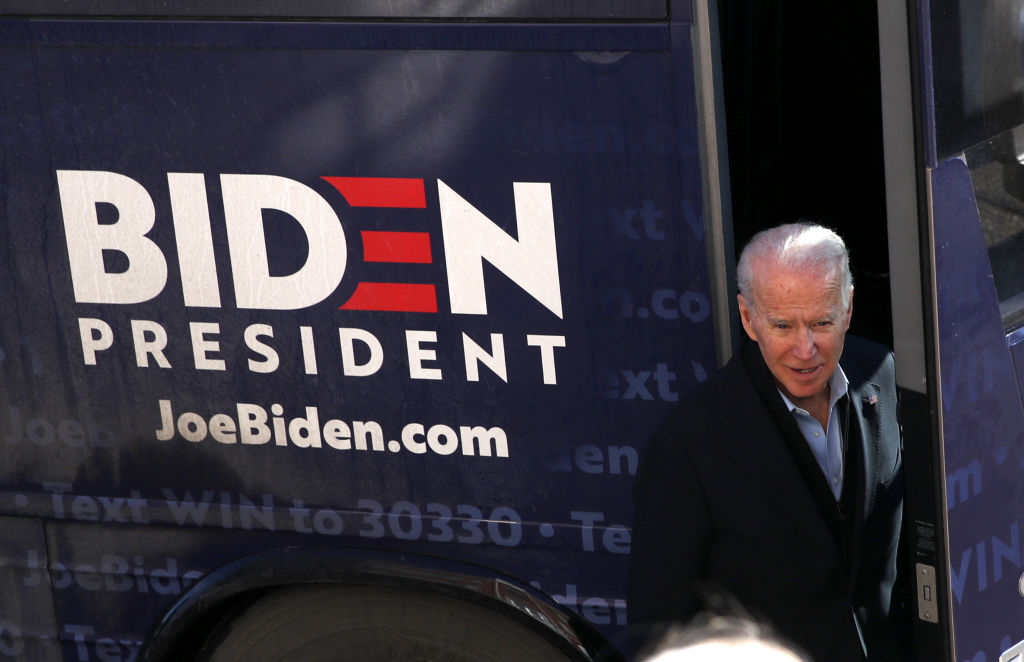

When President Donald Trump contracted COVID-19 in October 2020, questions swirled about what would happen to his spot on the ballot if he died or became incapacitated before Election Day. The same questions are resurfacing this cycle, given that the presidential frontrunners for the 2024 election—President Joe Biden and Trump—are 80 and 76 years old, respectively.

Privately, Democrats in the president’s orbit admit they are worried Biden may have age-related health complications on the campaign trail. Of particular concern, according to a senior Obama administration official, is the possibility that Biden would have a health episode in the final months of a general election campaign, raising doubts about Biden’s suitability for office or that he may need to be replaced on the ticket.

What happens when a candidate dies or becomes incapacitated after winning a party’s nomination?

The most recent national ticket candidate switch after a nominating convention occurred in 1972, when Democratic presidential candidate George McGovern tapped Sen. Thomas Eagleton at the last minute to serve as his running mate. McGovern soon discovered that Eagleton had been hospitalized three times for depression and undergone electroshock treatment. Eighteen days after securing the Democratic vice presidential nomination, Eagleton withdrew under pressure from McGovern and was replaced by Sargent Shriver. Republican presidential nominee Richard Nixon won the general election in a landslide.

Both the Republican National Committee (RNC) and Democratic National Committee (DNC) have rules in place governing how to fill presidential and vice presidential vacancies in the event of a death, incapacitation, or, in Eagleton’s case, a public relations nightmare.

Under GOP rules, for example, the RNC’s 168 members–representing all 50 states, the territories, and the District of Columbia–would be responsible for picking a replacement by majority vote. Three members from each state—state party chair, national committeeman, and national committeewoman—would cast the same total number of votes their state was entitled to cast at the nominating convention. If the three RNC members representing Montana disagreed on a particular candidate, the state’s votes would be equally distributed between the three (including fractional votes).

“It’s not one person, one vote,” said election attorney Michael Toner. “The three RNC members from California would be weightier than the three RNC members from Wyoming.”

The DNC’s bylaws have similar rules for nominating replacements. In the event of a national ticket vacancy, the DNC chair would call a special meeting of a majority of DNC members and elect a replacement via majority vote in accordance with the procedures established by the Rules and Bylaws Committee.

The vice presidential candidate would immediately surface as the most obvious replacement for a presidential nominee in either party, but wouldn’t be a shoo-in. “The backroom dealings of trying to figure out who the new nominee should be and just all that goes into that—I can’t imagine a more interesting and entertaining show in politics,” said Chris Gober, who practices constitutional law.

What happens if a candidate dies or becomes incapacitated before Election Day but after early voting has started?

Elections are administered on the state level, so ballot access would be a challenge for either party. At each national convention, the Republican and Democratic parties send certificates of nomination to each state and rely on them to place and print those names on the general election ballot.

If a problem with a nominee arises, the ultimate outcome depends on the states themselves.

“Some states you’re able to substitute somebody if they haven't printed the ballots. In other instances, you can’t, beyond certain deadlines,” Gober said. In other states, he explained, the only way to vote for a replacement nominee would be through a write-in campaign. Still others require electors to vote for the candidate who secured the popular vote.

In other words, chaos would ensue. “There would be concerns about voter confusion and whether the states were doing everything possible to print new ballots with the revised nominees in time for people to use them,” Toner said. “One thing we could predict is that there would be litigation, and the courts would have to try to grant some remedies.”

What if a president-elect dies or becomes incapacitated after Election Day?

Several things must happen after a nominee is elected, but before Inauguration Day on January 20. On Election Day, the presidential candidate must win 270 of the Electoral College’s 538 electoral votes. State laws determine when electors vote for a president and vice president. Then, Congress must certify the Electoral College results on January 6, before the swearing in of the Electoral College winner on January 20. If a president-elect died before the Electoral College vote, the party would likely coalesce around a replacement candidate chosen by the party.

What if the winner dies after the Electoral College votes?

This is where things become especially murky. Section 3 of the 20th Amendment of the Constitution says that if the president-elect dies, the vice president-elect is sworn in at noon on January 20 instead. The problem, though, is that the 20th Amendment doesn’t specify when the winning candidate becomes the president-elect, said Brian C. Kalt, a law professor at Michigan State University.

“The most common understanding of it is once the electors have voted, and not once Congress has counted those votes,” Kalt said. “We do have other statutory things like getting office space and transition funding, where someone gets designated as the president-elect. We don’t wait till January 6 for that.” Under that interpretation, Kalt said, the vice president-elect would assume the role of president in the event that the president-elect died after the Electoral College vote.

But that scenario also remains ambiguous, according to Gober.

“It’s gonna be the Supreme Court that ultimately decides what happens here,” he said. “There’s gonna be a massive amount of different interpretations that would make Bush v. Gore look like child's play compared to this morass.”

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.