DES MOINES, Iowa—In the wake of a once-in-a-decade storm, with snow still drifting over roads and temperatures in the negative teens, it was a small group that assembled Sunday morning at Fort Des Moines Church of Christ, a nondenominational congregation here in south central Des Moines. Pastor Mike Demastus, who has served at “The Fort” since 1998, has just launched a new sermon series on the book of Exodus and is preaching today on the account of the prophet Moses’ birth and rescue from the Nile River. But before he launches into that, he stops to offer “a couple of things I want to spend time and prayer about this morning.”

“I want to give as strong of an encouragement as I can to you to be involved tomorrow night, to go to the caucus. You have a civic responsibility as a believer in Jesus Christ to do it,” Demastus tells his congregants. “I believe that it’s not my role to tell you who to vote for. It is my role to tell you that you need to go to the caucus site and honor God with your vote. That’s it. And so, do your duty, go tomorrow, and caucus—caucus for King Jesus.”

This sort of thing might feel out of place in many churches, but here the congregants take it in stride. After all, Iowa’s evangelical Christians have long seen their first-in-the-nation caucuses as an unusually good chance to flex their political strength. Over the last two decades, they’ve repeatedly elevated underdog Republican presidential candidates cast from their own social-conservative mold, turning Mike Huckabee in 2008 and Rick Santorum in 2012 from also-rans into contenders and pushing Ted Cruz over Donald Trump here in 2016.

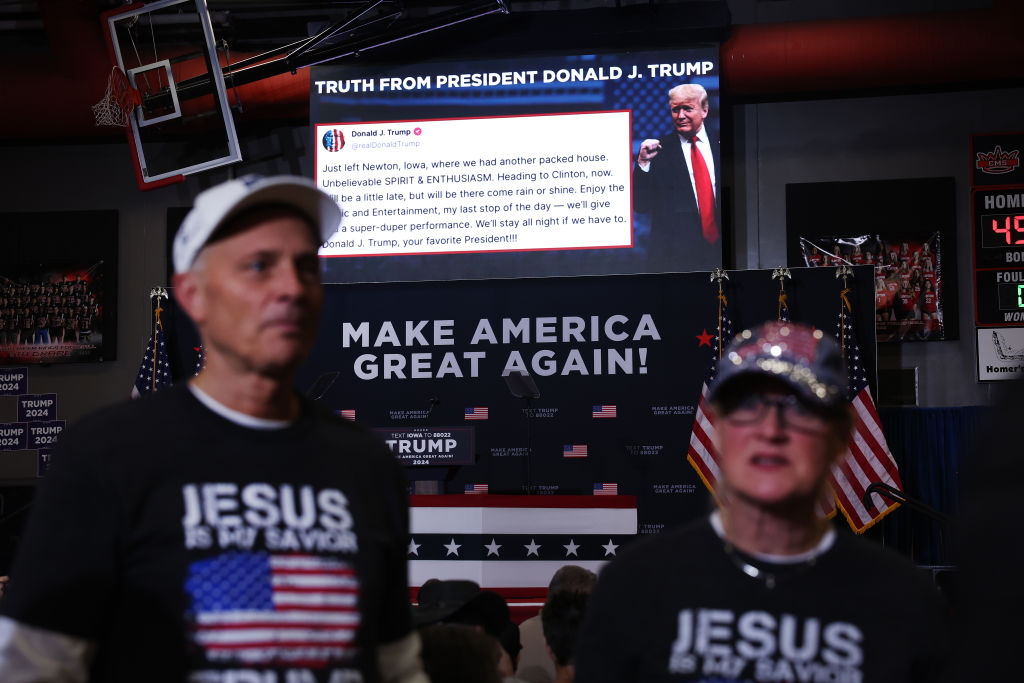

But Monday’s Republican caucuses are poised to deliver a much different story. The indisputable frontrunner, Trump, scores poorly on the old evangelical metrics—personal character, cultural similarity, rock-ribbed opposition to legal abortion and gay marriage. In place of all that, the former president offers something different: an oafishly reconstructed Messiah narrative in which he stands in for Christ as his supporters’ suffering savior from cultural forces they hate.

“God said, I need somebody who will be strong and courageous,” intones the narrator in a video Trump has taken to playing at his campaign appearances. “A man who cares for the flock. A shepherd to mankind who won’t ever leave nor forsake them. I need the most diligent worker to follow the path and remain strong in faith and know the belief of God and country … so God made Trump.”

For some evangelical pastors, such comments about Trump are repellent—not just not Christian but genuinely diabolical.

“We seem to be warned of many anti-Christs that would come—in other words, people that stand opposed to the principles of Christ, yet somehow gain the ear and the support of believers because they’re deceived by people like that,” Barron Geiger, a pastor at Southeast Polk Family Church east of Des Moines, told The Dispatch this week. “I would absolutely put him in that category.”

Some evangelical political leaders, too, have signaled they still think the former president is a poor representative of their values. Bob Vander Plaats is president and CEO of the Family Leader, an Iowa group that bills itself as inspiring the church “to engage Government for the advance of God’s Kingdom and the strengthening of family.” This cycle, Vander Plaats endorsed a candidate who more closely resembles the family-values, social-conservative template of past candidates: Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis.

In theory, this should have been a race-altering move. Vander Plaats chaired Huckabee’s caucus-winning Iowa campaign in 2008, and his endorsements of Santorum and Cruz were widely seen as major factors in their come-from-behind Iowa wins.

Instead, the latest polls show DeSantis is rolling into caucus day with just 16 percent support, his lowest share among Iowans to date, far behind Trump (48 percent) and even trailing former South Carolina governor and ambassador Nikki Haley (20 percent). Unless the polls are way off, whatever caucus magic guys like Vander Plaats used to wield appears to have weakened considerably.

To understand how the spell faded, it’s helpful to consider why it was that conservative Christians were so powerful in Iowa politics in the first place. Like other Corn Belt states, Iowa’s most notable demographic characteristics are that it’s quite white and quite rural, but it’s never been significantly more religious than its neighbors, and the state is significantly less religious than many states in the South.

Rather, Iowa evangelicals acquired their powerhouse reputation through years of diligent organizational effort. As Republican presidential candidates descended on the state cycle after cycle in hopes of launching into primary season with a strong showing, evangelical groups like Vander Plaats’ kicked their tires on hot-button social issues, then worked hard to boost the fortunes of those who measured up.

By their nature, the Iowa caucuses place a much higher premium than primaries do on voter enthusiasm and political organization. Conservative Christians, primed to think of themselves as an ideological bloc and already heavily networked through their churches, were ready to mobilize at scale and were thus consistently able to punch far above their not-insignificant numerical weight.

At the same time, even as Iowa evangelicals’ political power was growing, their raw numbers were beginning to shrink. Like the rest of the country, Iowa was experiencing the rise of the so-called “nones”—people with no religious affiliation at all—a group that had been growing steadily since the turn of the millennium.

But what really changed the character of evangelical voting wasn’t people losing their faith, precisely—it was a changing sense of what people considered their own faith to mean. Many professing believers stopped going to church, a trend accelerated by the rise of the internet and social media, the gradual retreat of many Americans from social institutions in general, a conservative population that increasingly saw its own churches as growing more liberal, and a global pandemic. The result was an evangelical populace that was far less of a constellation of little communities and far more an undifferentiated mass of online individuals than it had been two decades before.

“Evangelicalism used to be very top-down,” Ryan Burge, a Baptist pastor and data scientist who studies the intersection of religion and politics in America, told The Dispatch. “Social media has allowed us to become a bottom-up society. So now you can build your own little fiefdom through Facebook or Twitter or TikTok or YouTube.”

Burge argues that activists like Vander Plaats no longer hold the same sway in Iowa because the information networks that used to give them their authority have been completely upended.

“Bob Vander Plaats is a guy who had a ton of power,” he said. “Today he has no power, because he’s an old-guard kingmaker when no one wants that anymore. They want the interesting guy on YouTube or TikTok to tell them what Trump’s up to on abortion or what’s going on in Iowa right now. And I think that’s the big shift, is that no one speaks for evangelicalism anymore. No one. Because it’s a community of like 50,000 micro-influencers.”

Some faith-based political groups continue to argue that, while these trends present real challenges for American Christianity, they have had much less of an effect on Christians’ political salience.

During the COVID pandemic, “there were a lot of people who started watching church remotely, or they stopped attending at all. And I’m not going to lie to you, it’s been hard to get those people to come back,” Ralph Reed, founder and chairman of the Faith & Freedom Coalition, told The Dispatch on a press call last week. “But that does not mean those people have lost their faith. It doesn’t mean they don’t believe in God. It doesn’t mean they don’t believe in a higher power. It doesn’t mean they aren’t reading their Bible. It doesn’t mean that faith-based appeals won’t work for those voters.”

But the question at hand is, which faith-based appeals? That Christians have a civic duty to caucus, as Demastus tells his congregation? Or appeals like Trump’s, that God has appointed him a “shepherd to mankind” who has allowed himself to become a martyr to the left because he wants to protect his people from their depravities?

This sort of religiously charged appeal from Trump, Burge says, “really resonates with a lot of cultural evangelicals, because for them religion is nothing more than an identity. It’s a tribal marker: I’m a white Christian. It doesn’t have that second layer of theology about forgiveness and reconciliation and all those things.”

That’s not to say that all Trump-supporting evangelicals have left the church or stopped caring about Christian doctrine. But it’s unmistakable that Trump support among evangelicals strongly correlates with the sort of deep suspicion of the church as an institution that was far rarer decades ago.

“Our country is losing its moral values,” Hud Lainson of Urbandale, Iowa, told The Dispatch at a Trump event last week. “The churches have been going soft for several decades. But those of us that are strong believers have not stood up against that. And I take part of the blame for that, because I did not either.”

“What’s happening now is the churches that used to be conservative, very evangelical, they’re focusing more now on helping the poor, focusing on the poor, doing things for the poor, less fortunate,” Hud’s wife, Viv Lainson, added. “And they really miss the whole picture of really what God’s word teaches us, how we need number one to be concerned about people’s souls.”

For some pastors, all this mess is the result of the church thinking it could safely throw itself into the political process in the first place. Asked about many evangelicals’ increasing fears that Christians are under threat of persecution, Geiger brought up the ancient church under Rome. “These guys were trying to live peacefully under guys like Nero, and they had no political power whatsoever,” he said. “And they were growing like crazy despite the fact that they had zero political influence or power. Yet the church seems to think that their existence is threatened and their values are threatened if they don’t have the right people in office, let alone the right judges in place and all that kind of stuff.”

“That’s what I keep trying to get people to understand—it’s not our job to stop these things,” said David Harper, a pastor who serves alongside Geiger at Southeast Polk Family Church. “The only way they feel like things can be changed is through power. Which is ultimately what government and politics are, is power.”

“Well, once you start down that path,” he went on, “power is gonna—I feel for them, I know what they’re saying, and we’ve got a lot of people in our congregation that feel that way—but we keep trying to get them to understand that the way to change it is not to fight fire with fire, the way to change it is for me to live my life in such a way that people see Jesus through me and glorify God because of that.”

Despite what the polls say, Demastus thinks talk of evangelicals’ support for Trump is heavily overblown. “I believe you’re going to see Ron DeSantis take the first spot,” he told The Dispatch last week. “I think you’re gonna see Trump take number two, and I think probably a big surprise for a lot of people will be to see Vivek Ramaswamy come in third place, and Haley drop down to fourth.”

On Sunday, he stayed neutral. “I pray, God, that tomorrow you would help us remember you are Lord over caucus in Iowa,” he prayed from the stage. “You preside over all that’s going to occur. And help us, God, as a people to honor you by being present and voting in a way that honors you. Voting biblically.”

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.