This summer marks three years since the United States embarked on a new and massive industrial policy experiment, with President Joe Biden signing the CHIPS Act and Inflation Reduction Act in July and August 2022, respectively. Capitolism has repeatedly expressed concerns about those laws, based on both U.S. industrial policy’s long history of challenges and snippets indicating that the same old problems are reemerging once again. You might recall, in particular, that I’ve been skeptical of the widely touted increase in U.S. manufacturing construction spending, not because it was fake (though inflation surely has tempered the spending’s real dollar-value) but because we simply didn’t yet know what all those dollars were getting us. Now that we’re at three years, however, the picture is becoming clearer—as are some of the industrial policies’ large and unseen costs.

Intel and the ‘Ghost Factories’

The obvious place to start is with still-struggling Intel. The recipient of the CHIPS Act’s largest grant (along with billions more in tax credits) confirmed last week that it will again delay completion of the first phase of its Ohio mega-complex to at least 2030 or 2031. As you may recall, Intel’s now-“retired” CEO announced the Ohio project in 2022 as part of the company’s rather blatant push to get the CHIPS Act passed, promising the complex would be operational this year. Now, however, the Ohio facility’s future is in doubt, as Intel’s new CEO is cutting back on capital expenditures—he believes the previous management overinvested (gee, I wonder why?)—and recently suggested the company might abandon advanced chipmaking altogether. Some analysts also believe that Intel should abandon chip manufacturing to focus on other core businesses, but—given the company’s domestic manufacturing footprint and political importance—they’re skeptical that the U.S. government would let that happen.

This is not, to put it mildly, a great situation.

As a non-paying reader, you are receiving a truncated version of Capitolism. You can read Scott’s full newsletter by becoming a member here.

Of course, not all CHIPS Act headliners are doing as badly as Intel, but others’ U.S. projects also raise concerns. Industry leader TSMC, for example, is now producing some advanced semiconductors in Arizona, but—as National Review’s Dominic Pino reported last October—that facility wasn’t spurred by CHIPS money. We’ve discussed, moreover, that the Arizona factory’s current output is less advanced than its best Taiwan-made chips, relatively small, and relatively costly. TSMC doubled down on that last point in April when it hiked U.S. prices substantially, and the most recent figures put its Arizona-made chips at 5 to 20 percent pricier than those from Taiwan. More and better U.S.-made chips are coming from TSMC, but—as Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent just lamented—the fully operational Arizona factories will satisfy just 7 percent of U.S. demand and are also being further delayed by high costs and red tape. (And they’re still being flown to Taiwan for packaging—at least for now.)

Speaking of red tape and delays, Micron’s huge memory chip facility in upstate New York hasn’t even broken ground yet and won’t do so until at least late November, thanks in large part to state and federal environmental regulations and other CHIPS Act requirements (including social policy ones). Given that Micron still “needs to obtain dozens of permits, from the federal Environmental Protection Agency to the town of Clay,” even this new timeline appears optimistic. Regardless, the current best case is that Micron’s first factory won’t come online until 2029 and its entire complex won’t be cranking until 2045. (Anyone wanna bet?) And analysts doubt that the struggling firm’s New York output will be “cost competitive.”

Other subsidized New York semiconductor facilities, it should be noted, are suffering similar delays.

Samsung’s big facility in Texas has also struggled, with its opening delayed to 2026 in part because of technical problems and a disturbing lack of demand. A newly announced deal with Tesla could improve the situation there, but it’s incredibly risky given Tesla’s history of overconfident claims and Samsung’s recent lagging performance versus foundry rival TSMC. Even if successful, moreover, deliveries of the Tesla chips probably won’t start until 2028, and in the meantime, Samsung has “virtually no customers” lined up.

These issues might explain why Congress just quietly increased CHIPS Act tax credits in the OBBBA, thus funneling billions more to U.S. projects that have already been announced (and itself not exactly a great sign of how things are going in the U.S. semiconductor ecosystem).

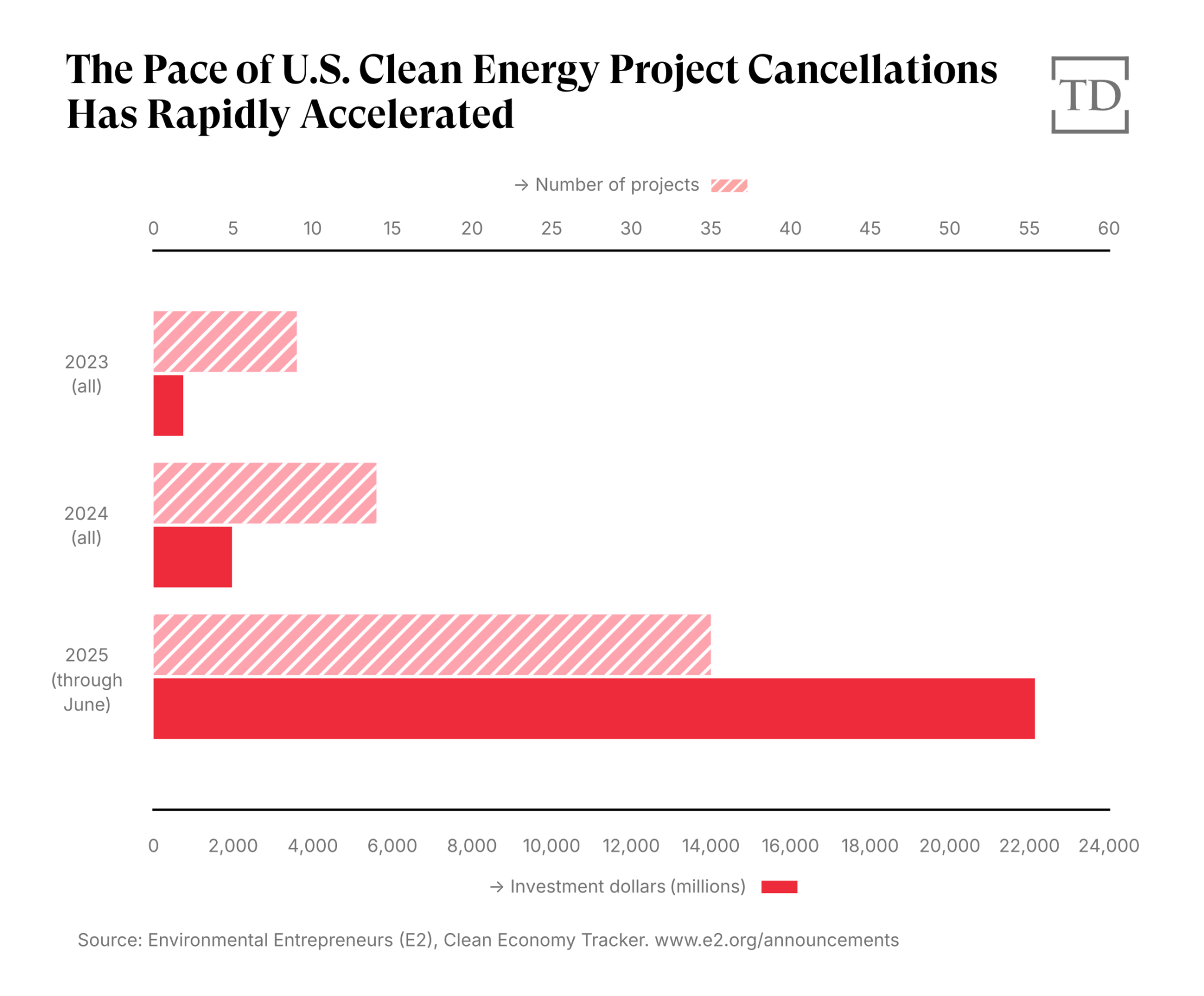

Factories subsidized by the IRA have also encountered increasing difficulties. The advocacy group E2, for example, calculates that 58 “clean energy” projects totaling almost $25 billion in private investment have been canceled, closed, or downsized since 2023—a pace that has rapidly accelerated in the first half of 2025:

This $25 billion represents almost 20 percent of all clean energy projects announced since 2022 and doesn’t include the federal, state, and/or local subsidies that are typically attached to these projects. The bulk of the factory closures, the organization notes, came from just four industries—batteries, EVs, solar, and wind—and almost entirely in manufacturing (as opposed to power generation). And the E2 list expressly omits projects and facilities that have been merely delayed or idled.

Including the paused projects would undoubtedly increase the total number of distressed clean energy investments in the United States today—and the potential waste spurred by the IRA. Indeed, it seems these days that not a week goes by without news of another green energy manufacturing project getting delayed (or worse). As Bloomberg reported earlier this month, in fact, “dozens” of “ghost factories”—planned green energy facilities that were started but now canceled—have popped up across the country, thanks to a combination of Trump administration hostility toward green energy, certain subsidy conditions, and various market factors (“soaring costs, high interest rates and slow-growing EV demand”).

Several other projects, Bloomberg noted, have been delayed or downsized, and analysts expect even more reductions and cancellations in the months ahead as Republican-led cuts to IRA subsidies and related Trump administration actions start to bite (see last week’s newsletter for more). The risk, Bloomberg noted, is not only billions of wasted taxpayer dollars but a “sizable amount” of “stranded investments.” Yikes.

Of course, many subsidized projects aren’t dead or dying today, and it’s still too early to declare the CHIPS Act and the IRA total failures. On the flipside, many semiconductor and green manufacturing projects would certainly have happened without all the subsidies – something even advocates acknowledge. Regardless, the U.S. manufacturing construction wave does seem to have crested, and the United States’ “ghost factory” problem—which reeks of Chinese industrial policy, by the way—does seem to be getting worse. None of this bodes well for U.S. industrial policy.

Relearning Lessons

The reasons for these difficulties are, as devout Capitolism readers know, just what critics warned years before the CHIPS Act and IRA became law. Market factors like consumer demand, interest rates, and construction costs are notoriously difficult for anyone—but especially politicians—to predict years in advance, as are the technologies and companies that will win the distant future. Industrial policies also often favor older, politically connected incumbents like Intel (or First Solar) instead of smaller players on the cutting edge but without a big lobbying budget. When the CHIPS Act was first working its way through Congress, for example, ChatGPT didn’t exist and Nvidia was still a “video game company” with a share price well under $10. So, even in 2024, it was long-struggling Intel winning the most government support.

It’s also common for government-backed projects to stagnate when confronted with old policies—environmental regulations, trade and immigration restrictions, labor requirements, sanctions, etc.—or new “Everything Bagel” conditions attached to the new laws during their formulation or implementation, in order to appease influential groups like labor unions (itself a potential industrial policy problem!).

After three years of CHIPS and IRA subsidies, we can see in the above reporting and elsewhere that these common industrial policy impediments are causing problems once again.

The biggest impediment, however, may simply be the political uncertainty baked into any large-scale U.S. industrial policy, especially in today’s hyperpartisan environment. As we discussed last year (and the year before that), uncertainty is always a problem with industrial policies, but the risks were especially apparent as trillions of dollars in new federal subsidies proved to be irresistible political catnip for President Joe Biden and congressional Democrats. All those “Bidenomics” photo ops, in turn, triggered a predictable backlash among many Republican voters and politicians, regardless of the projects’ possible merits.

Combine that negative partisanship with more principled and substantive subsidy opposition from many free marketers and a broad Republican victory in 2024, and we got a 2025 investment environment much more hostile to the very things the federal government was encouraging mere months earlier—a bad situation then turbocharged by actual cuts to the IRA subsidies as part of the OBBBA. Even CHIPS Act implementation has been in some doubt this year, despite more bipartisan support and a recent increase in the tax credits.

This political risk was obvious years ago, but—as Biden climate alumna Jane Flegal just put it on Ezra Klein’s podcast—it’s now something many IRA advocates belatedly seem to recognize:

One thing that I have learned throughout this process is that climate politics is inseparable from all of our other politics. So going back to the election, part of what happened here was we passed the I.R.A. as a Democrat-only bill.

We live in a world now, where when that happens, there is a tendency to turn up the polarization on whatever is in the Dem-only bill on the other side of the aisle. This bill was framed as Biden’s signature climate achievement. It’s not, in some ways, surprising that the Republicans wanted to tear it down.

Thus, Klein sums up, green energy subsidies—especially for wind, solar, and EVs—“became political culture-war issues” instead of scientific or economic ones. And he, Flegal, and other U.S. climate hawks are now pivoting to broader supply-side reforms—permitting, especially—that have far more buy-in from Republicans (and many experts, too). “[T]he most important thing we can do going forward—if we take affordability seriously and we take climate seriously—is remove all of the nonmarket barriers to deploying this stuff as rapidly as possible everywhere,” Flegal concluded (and to take on another influential interest group, the “environmental movement,” in the process).

She’s not alone among the Biden alums in reconsidering their subsidy-heavy approach. And, to be clear, a supply-side pivot is smart for political and economic reasons. It’s just a shame that they didn’t start with that stuff instead of all the costly and troublesome subsidies. We’d be in a much better place today if we had.

Just How Much Waste?

At this point, of course, the subsidy cake is pretty well-baked, and the current situation for both the IRA and the CHIPS Act may reteach us another industrial policy lesson: Government “support” can generate a very large amount of public and private waste.

We’ve already discussed, for example, some of the offshore wind power projects that were started and then canceled. Bloomberg’s “ghost factory” piece also documents several empty plots of land or half-finished factories that IRA subsidies encouraged. In my neck of the woods, a massive, vacant lot—supported by $450 million in state infrastructure enhancements—is the only tangible sign of a VinFast EV factory that was supposed to open last year but is now, to put it kindly, in limbo. A few miles away from that sits an almost-completed factory for chipmaker Wolfspeed, which had been banking on CHIPS Act funds but recently declared bankruptcy. Head South to Georgia, and you’ll see a half-finished-but-now-canceled factory of federal loan recipient Aspen Aerogels, which had already spent more than $300 million on the site. The list goes on.

And then there’s Intel. The Columbus Dispatch reports that the company’s Ohio facility has already received at least $1.5 billion in CHIPS Act grants, along with millions more in tax credits and state and local subsidies, including infrastructure that can’t be refunded. Intel itself has invested billions more in the site and the surrounding area, and other companies have spent money too in the hope of winning future business. While Intel and local politicians confidently say the facility will still be completed eventually—embracing the sunk-cost fallacy along the way—that optimistic future is clearly in doubt.

Regardless, the Ohio site and all the others like it across the country represent massive amounts of finite resources—time, money, materials, people, etc.—that could have been better spent without governments’ thumbs on the scale. In the case of lost taxpayer dollars and empty fields and buildings—something certainly not unique to recent U.S. industrial policy—the waste is easy to see. But, as seen in the U.S. steel and shipbuilding industries, and maybe soon with Intel, waste can also happen in factories that do become operational. In those cases, the facilities make things of political, not economic, value and are kept alive not by eager customers but by ambitious (or naïve) politicians and a perpetual stream of government support and protection. As those brand new CHIPS subsidies and yet another solar tariff case indicate, just three years into our grand industrial policy experiment, there will be a lot more of this waste to come.

If so, it’ll be yet another industrial policy risk we’ve long understood – and another lesson we’ll be forced to relearn.

Chart(s) of the Week

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.