Dear Capitolisters,

Almost exactly a year ago, I took to these pages to lament and correct the emerging consensus in Washington that China’s economic rise justified a broad rejection of free markets and a warmer embrace of “China-style” industrial policy and economic planning in the United States. At the time, this view was perhaps somewhat risky—China, as you may recall, seemed to be navigating the pandemic pretty well, with various economic and COVID-19 metrics (at least publicly) looking good by international comparison. The United States, meanwhile, was just emerging from its pandemic slumber (thanks, vaccines!), and various pieces of industrial policy legislation—most notably the massive United States Innovation and Competition Act of 2021—seemed to be quickly heading for President Biden’s desk with overwhelming bipartisan support.

In the last year, however, the script has been—as the kids say—flipped. The pandemic and economic policies that seemed to be fueling China’s rise now seem to be an anchor, and the United States—though surely challenged by inflation and other discrete policy issues (labor shortages, supply chain stuff, etc.)—seems to be back on or even above its pre-pandemic economic trends, even as that industrial policy bill remains incomplete. And here lies, I think, an important lesson about not only the “China threat” but also U.S. policy and our long and misguided love affair with economic pessimism.

Snap Back to Reality

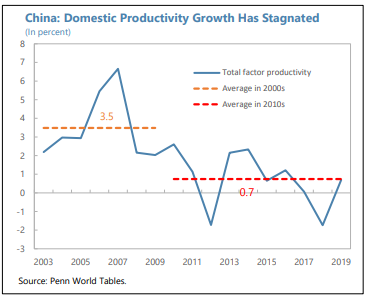

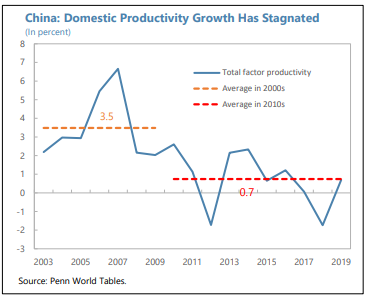

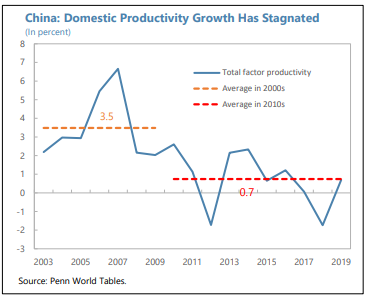

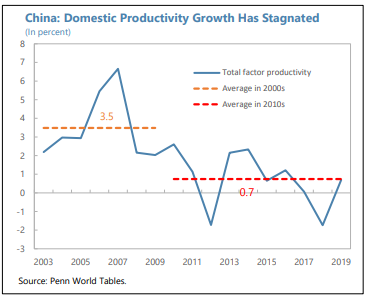

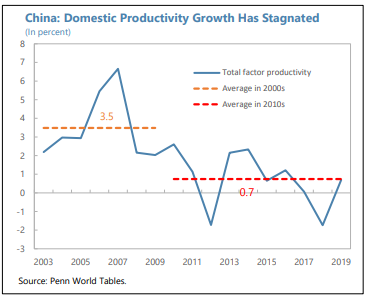

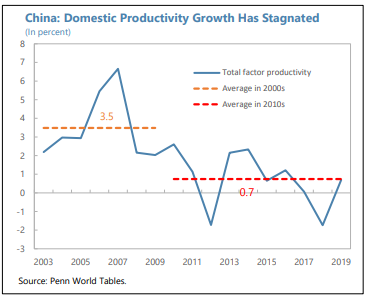

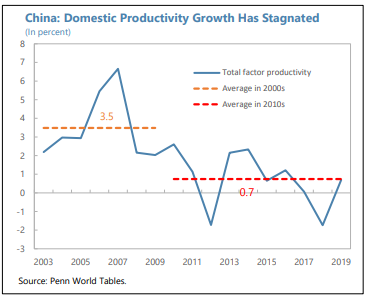

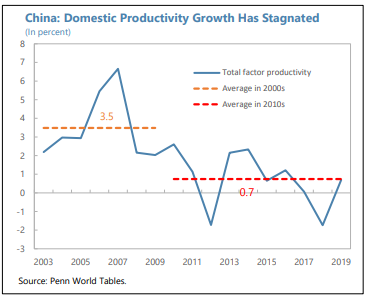

In some cases, China’s specific challenges remain the same as the ones I laid out last year—only with new information. For example, a new report from the Center for Strategic and International Studies finds that Chinese industrial policy—subsidies, loans, state-directed investment, and other incentives to favored companies and industries—has been far costlier than previously estimated (while still producing the same distortions and underwhelming results). In fact, the latest International Monetary Fund “Article IV” report on China’s economy finds that its state-owned enterprises (SOE)—a major and growing conduit for Chinese industrial policy—are 20 percent less efficient than private sector actors, and that “market dynamism and productivity growth have slowed and are unlikely to revive in the absence of SOE and competitive neutrality reforms.” China’s productivity thus remains well below developed country “frontier” levels—levels the IMF doesn’t believe China can reach without significant SOE and other structural market reforms (that Beijing seems wholly uninterested in taking).

China’s demographic challenges also remain severe—despite government attempts to fix them. As Carl Minzer detailed in Foreign Affairs last month:

Officials initially assumed that merely rolling back long-standing state restrictions would boost birth rates. In 2013, Beijing announced that couples would be allowed to have two children if one parent was an only child. In 2016, the one-child policy was formally scrapped in favor of a two-child policy; in 2021, it became a three-child policy.

But it was all to no avail. China’s birth rates have continued to plummet. In 2021, they fell to the lowest level since the famine-induced years that followed the Great Leap Forward in the late 1950s. As a result, China’s official total fertility rate (TFR)—or the number of children that would be born to a woman if she were to experience current age-specific fertility rates throughout her reproductive years—has declined to 1.3. Some observers believe the true figure to be closer to 1.1, on par with that of other rapidly aging societies in East Asia.

A couple months earlier, a member of the People’s Bank of China’s monetary policy committee speculated that China’s population actually peaked this year, further dragging down the Chinese economy: “With a declining labor force already acting as a constraint on the supply side of the economy, a shrinking population will become a new restriction on the demand side.” As the IMF noted in its report, a slowing population will also weigh on China’s economic dynamism and productivity growth.

Minzer adds that new Chinese government efforts to boost fertility, such making divorce more difficult, might actually make things worse (meaning even fewer babies) in the coming years.

China’s debt situation also has deteriorated further—increasing by $2.5 trillion in the first quarter of 2022 alone. Problems are especially acute in China’s property sector, which has long driven economic growth there:

Builders and regulators are counting on banks to provide a lifeline to the industry as bond funding and home sales dry up. Yet developers’ cash flows from bank loans have plunged almost 30% in recent months, undermining President Xi Jinping’s efforts to arrest a property slump that’s worsening a slowdown in the world’s second-largest economy.

As the number of developers that have defaulted on or extended debt obligations mounts, banks are reluctant to increase their exposure to the sector in response to regulators’ demands. Some are only rolling over debt to prevent a souring of loans, the people said.

Defaults in the sector “continue at a record pace.” As noted in a recent Carnegie Endowment report, Chinese debt might not be a problem if it were still supporting productive endeavors like consumption and business investment like it did between 1970 and the mid-2000s, but today it’s generally not: “China’s surging debt burden is a function of nonproductive investment” (thanks, industrial policy!), and “[t]here is increasingly a consensus in Beijing that China’s excessive reliance on surging debt in recent years has made the country’s growth model unsustainable.” However, the report concludes by noting that Chinese policymakers aren’t yet willing to accept the economic costs—mainly, much lower economic growth—of shifting away from this model. So expect more distortions and continued malinvestment in the months ahead.

Based on these and other factors, an excellent new Lowy Institute report sees China experiencing a major growth slowdown in the coming years and never reaching U.S. levels of development: “China would still become the world’s largest economy, but it would never enjoy a meaningful lead over the US and would remain far less prosperous and productive per person even by mid-century.”

And this pessimism came before what’s inarguably been the biggest and most troublesome development in China since last year: the utter catastrophe of President Xi Jinping’s seemingly religious commitment to a “Covid Zero” strategy, even as the virus became far more contagious (and less controllable) and as mass-closures of Shanghai, Beijing and other major urban centers caused China’s economy to stall out, if not shrink altogether. As Bloomberg noted in late May, “China’s commitment to Covid Zero means it’s all but certain to miss its economic growth target by a large margin for the first time ever”—with optimistic “consensus” forecasts for annual GDP growth in China steadily declining and now well-below recent growth levels there (assuming the Chinese government doesn’t fudge the numbers via “statistical smoothing”):

Other forecasts are even gloomier. Bloomberg Economics, in fact, recently predicted that China’s economy will grow only 2 percent this year, and will be outpaced by the U.S. economy’s growth (2.8 percent) for the first time since 1976. That’s a big problem for an economy that’s still relatively poor, compared to the U.S. and other developed countries:

Bloomberg politely notes China’s “growth potential” in the chart above, but reaching that potential is the obvious challenge—especially given short-term Covid Zero problems (“China's economy is going backwards”) and the long-term headwinds already noted above.

Slowing economic growth is a problem for any country, but it’s especially one for China, where GDP is seen as a way to maintain social order and project regime legitimacy at home and abroad:

While Chinese Communist Party rule may remain unassailable, senior leaders have an acute fear of social unrest, according to Bruce Dickson, a George Washington University professor and author of “The Party and the People: Chinese Politics in the 21st Century.”

Party leaders “want to avoid an economic slowdown that would create job losses and increase the likelihood of protests,” said Dickson. “Maintaining growth is seen as the best way to maintain stability.”

Growth is increasingly seen as an international security issue, too. The Wall Street Journal (citing unidentified sources) reported this week that Xi told his deputies to make sure China’s economic growth outpaces that of the U.S. in 2022.

That last part just screams “legitimacy,” eh?

Anyway, to maintain growth and “arrest a rapid deterioration in the country’s economic outlook,” China’s government paused its monthslong regulatory crackdown on domestic tech giants like Didi (China’s Uber) and TikTok owner Bytedance—a rare, albeit implicit, admission of Chinese technocratic missteps. China has also pledged additional spending on more than 100 “major” infrastructure projects, even as many worry that this stimulus will crowd out other, more productive forms of spending.

Regardless, maintaining growth is an increasingly tall task, especially given China’s systemic challenges and Xi’s bizarre love of Zero Covid. The latter has even caused a messaging (if not more) rift between Xi, who adamantly supports the lockdowns and sees his own legitimacy as tied to their success, and the guy in charge of ensuring that the Chinese economy performs, Premier Li Keqiang, who has repeatedly warned of China’s troubling economic future (thanks to the lockdowns!). Such contradictions, in turn, have further harmed China’s economy, as lower-level bureaucrats in charge of effectuating government economic plans are torn between favoring Xi’s or Li’s priorities:

Yet many government officials charged with implementing policy at the ground level aren’t quite sure who to listen to: Xi continues to emphasize the need for officials to push for zero Covid-19 cases, even as Li continuously urges them to bolster the economy and hit preordained growth targets.

That dilemma is leading to paralysis within a nation normally hailed for speedy implementation of diktats from above, according to eight senior local government officials and financial bureaucrats who requested not to be named because they aren’t authorized to speak publicly.

China’s lockdowns now seem to be easing (maybe), so some semblance of policy coherence and order might soon return. But the reputational damage has been done. Critics have (rightly) noted, for example, that the last few months of Zero COVID insanity have been an indictment of autocracy (“a man-made crisis like the one in Shanghai is inevitable under China’s authoritarian system”) and top-down economic planning, causing long-term damage to China’s economy:

Now, in the name of pandemic control, the Chinese government is meddling with the economy in ways that the country hasn’t seen for decades, wreaking havoc on business….

“This is not only making it impossible for many private businesses to survive, but also accelerating outbound immigration and quickly dampening willingness to invest,” said Zhiwu Chen, an economist at University of Hong Kong. “Once people lose confidence in the country’s future, it will be extremely difficult for the economy to recover from the zero Covid policy’s impact.”

Other pandemic-related policies in China raise further questions about the regime’s competency and inevitability. For example, China’s stubborn refusal to embrace a Western mRNA vaccine (and continued use of inferior homegrown vaccines) has not only harmed Chinese citizens and prolonged the economy-crippling lockdowns, has been viewed by experts outside and inside China as a major “failure”:

The wait, many analysts believe, is for a local company to come up with its own mRNA vaccine. Since the start of the pandemic, Xi’s government has touted self-reliance in fighting Covid, promoting domestic vaccines based on inactivated versions of the virus and barring all foreign ones from the market. Slightly more than 88% of China’s 1.4 billion people have received two doses of those shots.

Opening up to foreign-made mRNA shots risks embarrassing Xi and other officials, says Allison Hills, senior consultant in London with Eradigm Consulting, which advises biotech and pharmaceutical clients. “For them to say now we are accepting BioNTech,” she says, “it’s tantamount to saying ours are not as good.”

The government has also been criticized for not prioritizing the elderly in its vaccination campaigns and, when they finally did try to get the oldsters vaccinated, opted for … egg incentives? None of this particularly reassuring (to put it nicely).

As a result of this mess, and surely aided by China’s cozy relationship with Russia, foreign capital has been fleeing China for months. In March, “China witnessed $17.5 billion worth of portfolio outflows…, an all-time high.” April saw similar moves, causing China’s currency to weaken rapidly.

Major companies have also started to look elsewhere for other manufacturing options. Apple, for example, is moving iPad production to Vietnam and telling its contract manufacturers to boost production there and in India (though it will still have a large presence in China). Other companies are doing the same: “Trade disruptions from China’s lockdowns and the war in Ukraine are seen doing for Southeast Asia what the US’s spat with Beijing couldn’t meaningfully do—redistribute supply chains.”

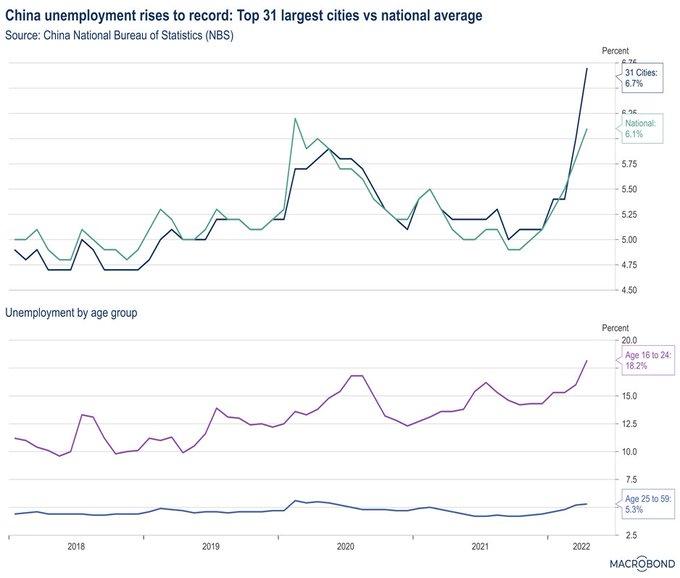

Other gray clouds are also on the horizon. Foreign teachers are abandoning ship, harming China’s international schools (which are important for luring overseas talent). China’s service sector—critical for the economy’s long-term health—is underinvested. And youth unemployment has skyrocketed, while “[j]ob prospects for graduates have also deteriorated significantly as the Chinese economy heads towards contraction.”

Given all of this, the once-invincible Xi (and, by extension, China) isn’t looking so invincible these days—even among Chinese policymakers:

Last year, President Xi Jinping seemed all but invincible. Now, his push to steer China away from capitalism and the West has thrown the Chinese economy into uncertainty and exposed faint cracks in his hold on power.

Chinese policy makers became alarmed at the end of last year by how sharply growth had slowed after Mr. Xi tightened controls on private businesses, from tech giants to property developers. Meanwhile, China’s stringent Covid lockdowns, part of Mr. Xi’s approach to handling the crisis, have ramped up again as Covid cases surge, hurting both consumer spending and factory output.

Add to that a pact with Russia in early February, just weeks ahead of its invasion of Ukraine, that has widened a gulf between China and the West and underlined how high the costs could be for China of implementing Mr. Xi’s agenda at home and in foreign policy.

And this was in March, before the lockdowns had exacted their massive economic (and reputational) toll.

Now, look, I certainly don’t think this means that Xi’s at much risk of being deposed or anything (see here for a reality check), or that the Chinese economy is on the verge of collapse (which, as my colleague Clark Packard just explained, would raise its own problems). And China can surely still cause plenty of headaches in the years ahead. But it’s beyond clear at this point that the supposedly unstoppable Chinese juggernaut—the one that supposedly justified abandoning American free market capitalism (or whatever)—has serious flaws, and that those flaws have been caused in no small part by China’s autocratic, state capitalist economic model.

So About that American Pessimism …

It’s also increasingly clear that the pervasive pessimism here regarding the supposed weakness of American capitalism in the face of the “China threat” is similarly misguided. Yes, undoubtedly, the United States faces real challenges—many of which emanate from our elected officials, by the way—but the America-doubting, China-praising demands for a major systemic overhaul (big changes, not small) seem to be swirling down the drain once again. Consider, for example, this recent embrace of the aforementioned industrial policy legislation, which concludes with this gem:

China has the benefit of planning for the long view. With a strong central government and a long history of industrial planning, it has a leg up against America. American policymakers must not allow their decentralized, federalist democracy to become a weakness in the race for the next semiconductor. As our Cold War history has shown us, democracy is our biggest asset to staying ahead of the curve. We just need to provide the resources, the funding and the direction to our strategic industries to keep them ahead.

Given the last year of Chinese struggles and American rebound—the latter fueled in no small part by the overwhelmingly successful “Western” mRNA vaccines and our relatively free and dynamic domestic markets—such claims seem increasingly wrongheaded (albeit comically so). Unplanned, decentralized democracy here may have (okay, surely has) its messes, but the system’s drawbacks are heavily outweighed by its advantages. It just usually takes a little while for the scales to tip.

National Review’s Kevin Williamson puts it well in a recent essay:

Americans wallow in doom and gloom, even though our fiscal policies belong to a nation of insane pie-in-the-sky optimists. We almost always overestimate the strength of the autocratic regimes and underestimate the strength of the liberal-democratic ones — we did it throughout the Cold War, and we have done it for decades with respect to China. And even among the liberal democracies, we Americans always overestimate the strength of our rivals and competitors and underestimate ourselves. There is much to admire about Japan and much to learn from the Japanese, but nobody is writing science-fiction novels about a world dominated by that aging, complacent, declining country anymore. Ezra Pound thought he saw the future in fascist Italy, while Lincoln Steffens visited the Soviet Union and declared: “I have seen the future, and it works.”

As it turns out, “what works” is the boring old stuff we have here: freedom, democracy, property rights, rule of law, modest regulation and light taxation, free trade, a culture of entrepreneurship, hard work. The United States isn’t the only country that has all that — but we are the biggest country that has all that, and we have oodles of it.

George Mason University’s Alex Tabarrok adds much the same in response to a recent question from AEI’s Jim Pethokoukis:

What do you make of the argument that China's recent industrial success, particularly in tech, points to a more viable industrial strategy than America's current approach?

Every generation launches a new competitor to America and the people who don't like capitalism and America's individualist, free market economy trumpet that now the American way is being left in the dust. In the progressive era it was the Germans (how did that work out?), then it was the Russians (remember Sputnik?), then it was the Japanese (buying up Rockefeller center! the horror!), then it was the Chinese (look at those high speed rail lines!). My message to Americans is to double down on America. Double down on immigration, entrepreneurship, innovation, building for tomorrow, free markets, free speech and individualism and America will take all new competitors as it has taken all comers in the past. The world should be more like America not the other way around.

Indeed, if the last year-plus has taught us anything, it’s that the greatest threats to America today don’t come from China or any other foreign country, but from our own policy action (or inaction) on trade, immigration, antitrust, individual rights, and other areas—mistakes that close us off from the world; inhibit dynamism and competition; empower central planners; and punish our most successful and innovative firms. Mistakes that are driven by a groundless lack of confidence in the American system (and the people living and working within it). The pessimists all seem to want to make America less American, and—as the “China Threat” withers like others before it—it’s long past time we ask them, “But why?”

Chart of the Week

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.