Dear Capitolistas,

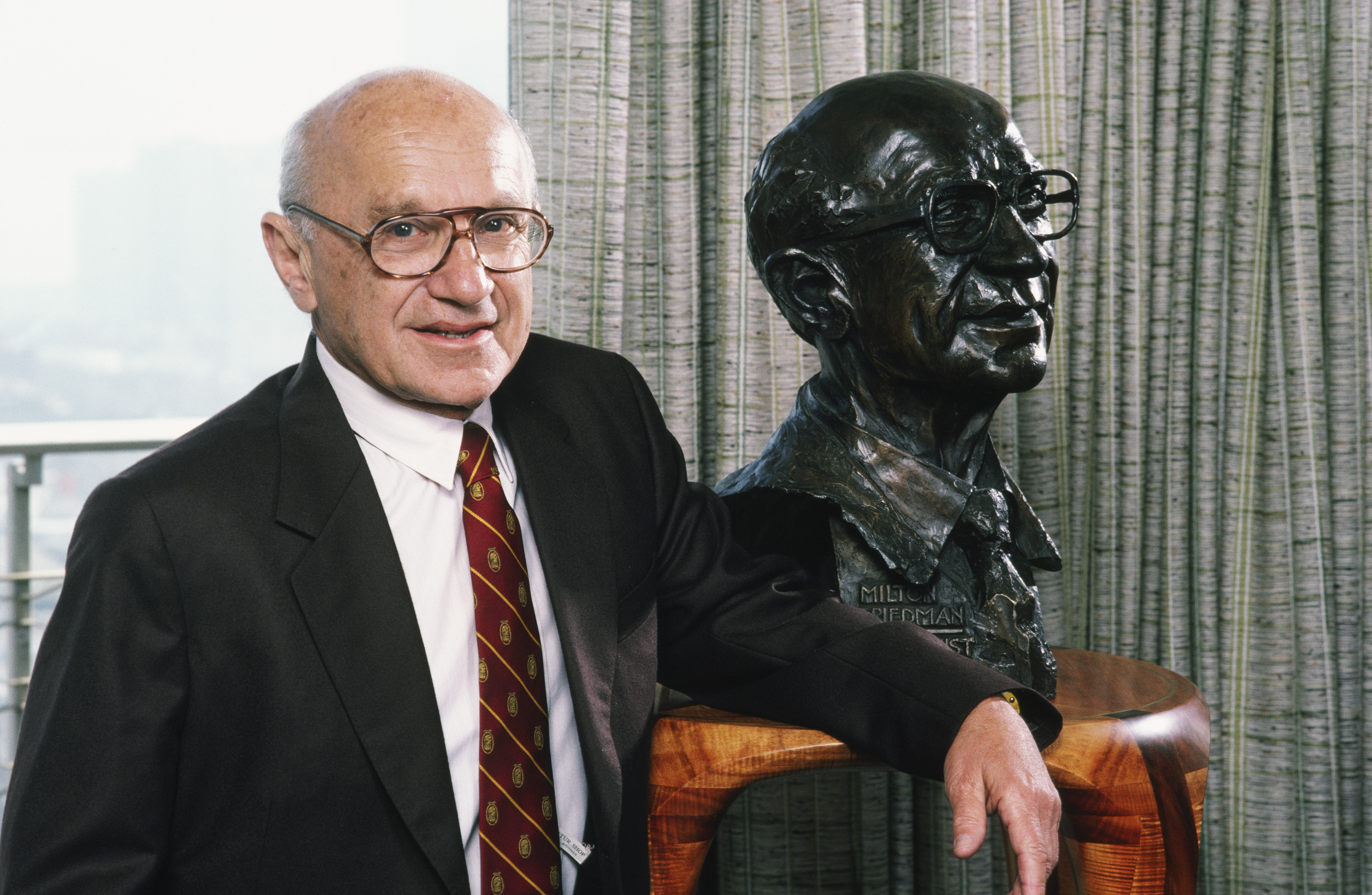

The New York Times recently celebrated the 50th anniversary of Milton Friedman’s influential New York Times Magazine essay, “The Social Responsibility of Business Is to Increase Its Profits” with a great idea: having Thought Leaders™ from across the political spectrum opine on the essay and its impact. The idea’s execution was, well, not as great. It honestly seemed like several people hadn’t even read the essay—or at least understood Friedman’s actual point—but that’s actually an issue for another time. Instead, I want to focus on the 3,000-word essay from Kurt Andersen that accompanied the NYT project—“How Liberals Opened the Door to Libertarian Economics”—because it hits on a theme that both the left and the right have recently embraced: the historical dominance of “libertarian economics” or, as Andersen puts it, “the full Friedmanization of our economy for the last four decades.”

That’s right. In case you haven’t heard, my fellow libertarians and I run Washington and have done so since the 1970s. No, really, stop laughing: Seemingly everywhere you look these days, you’ll find politicians and pundits on the right and the left blaming libertarians for whatever problems you, dear reader/viewer/donor/voter, see in America. As I noted to Jonah on The Remnant last year, the concept is laughable—and not just on foreign policy—to anyone who has worked in D.C. over the last several decades, but it nevertheless persists and motivates a lot of populist arguments and proposals.

It therefore deserves a more objective response, so that’s what we’re going to do today.

(WARNING: NUMEROUS CHARTS AHEAD, AND BEFORE YOU ASK: YES, ALL DATA ARE INFLATION-ADJUSTED UNLESS INAPPLICABLE OR OTHERWISE NOTED.)

Before we begin, some necessary context: First, as both history and many of the following charts show, U.S. economic policy in the ’60s was clearly not “libertarian,” following decades of government expansion and economic intervention through the New Deal, the Great Society, the Warren Court, trade and immigration restrictionism, and so on. (Friedman and other free marketers arose in response to this statism.) Thus, simply maintaining the status quo of this era would hardly be reason to declare libertarian victory. Second, even despite the above interventionism, the 20th century U.S. economy was generally more market-oriented than other countries, due in large part to their dabbling in socialism or communism during the same period and to factors inherent in the U.S. system like property rights and rule of law. This matters when considering, for example, global rankings of government spending or economic freedom—it’s all relative.

Now on to the show.

The size and scope of the federal government.

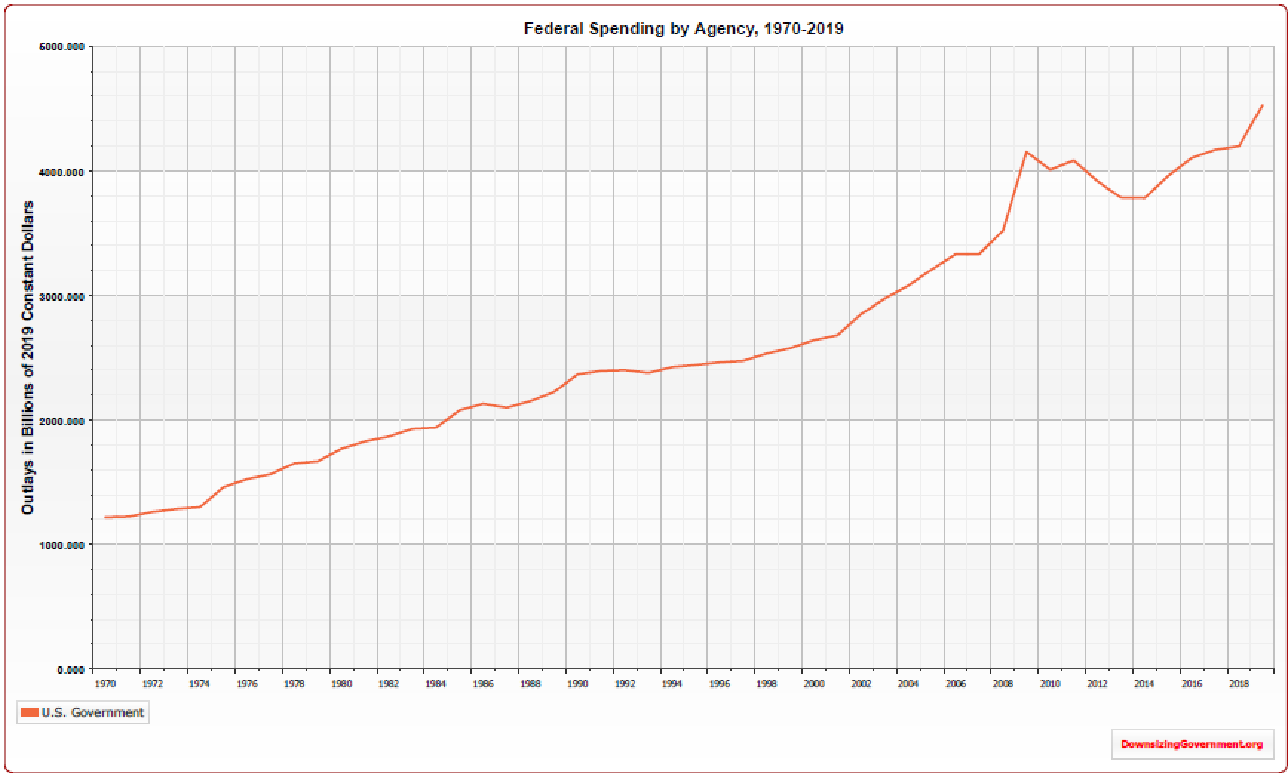

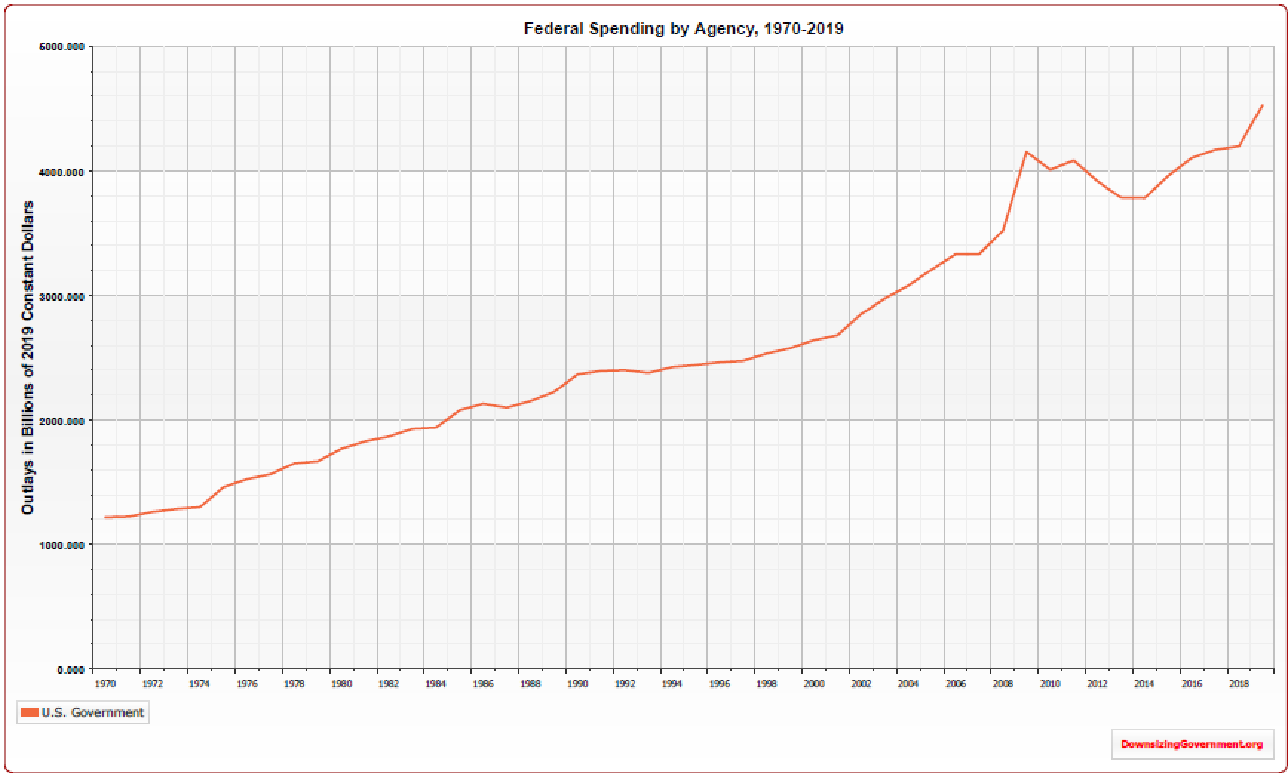

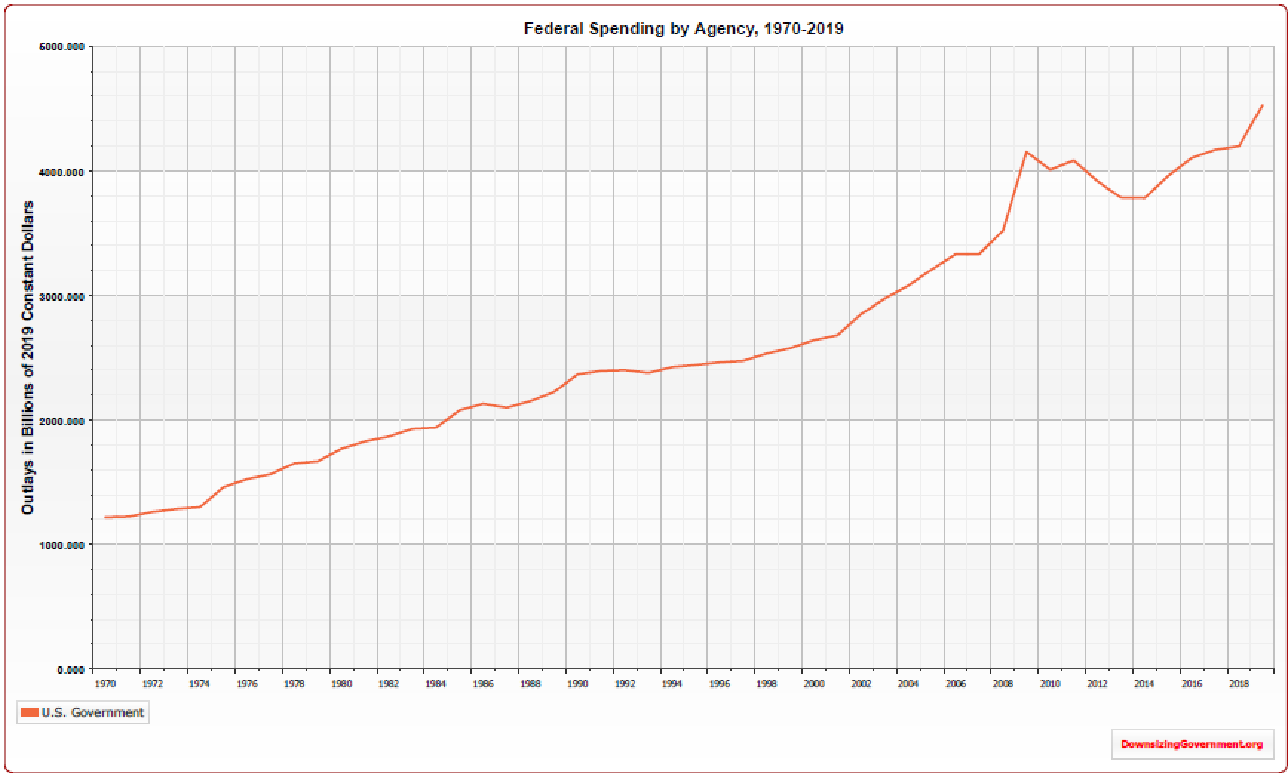

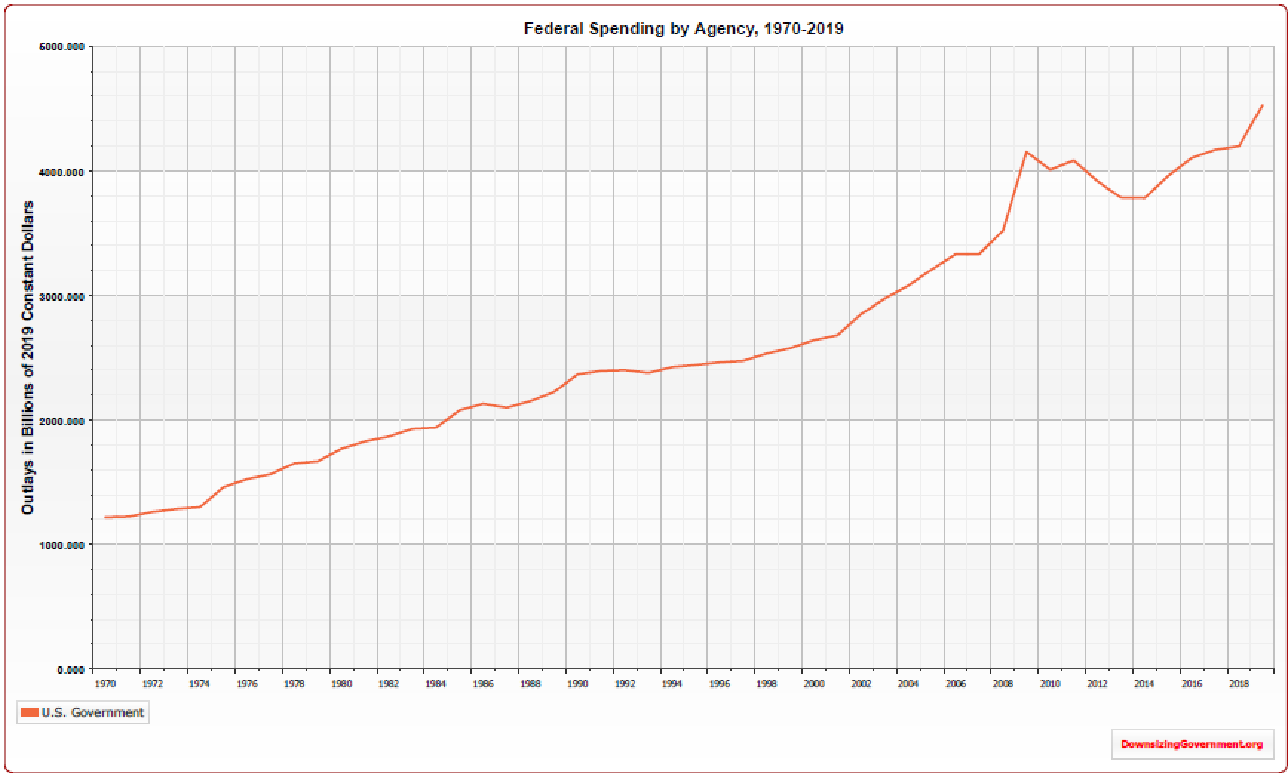

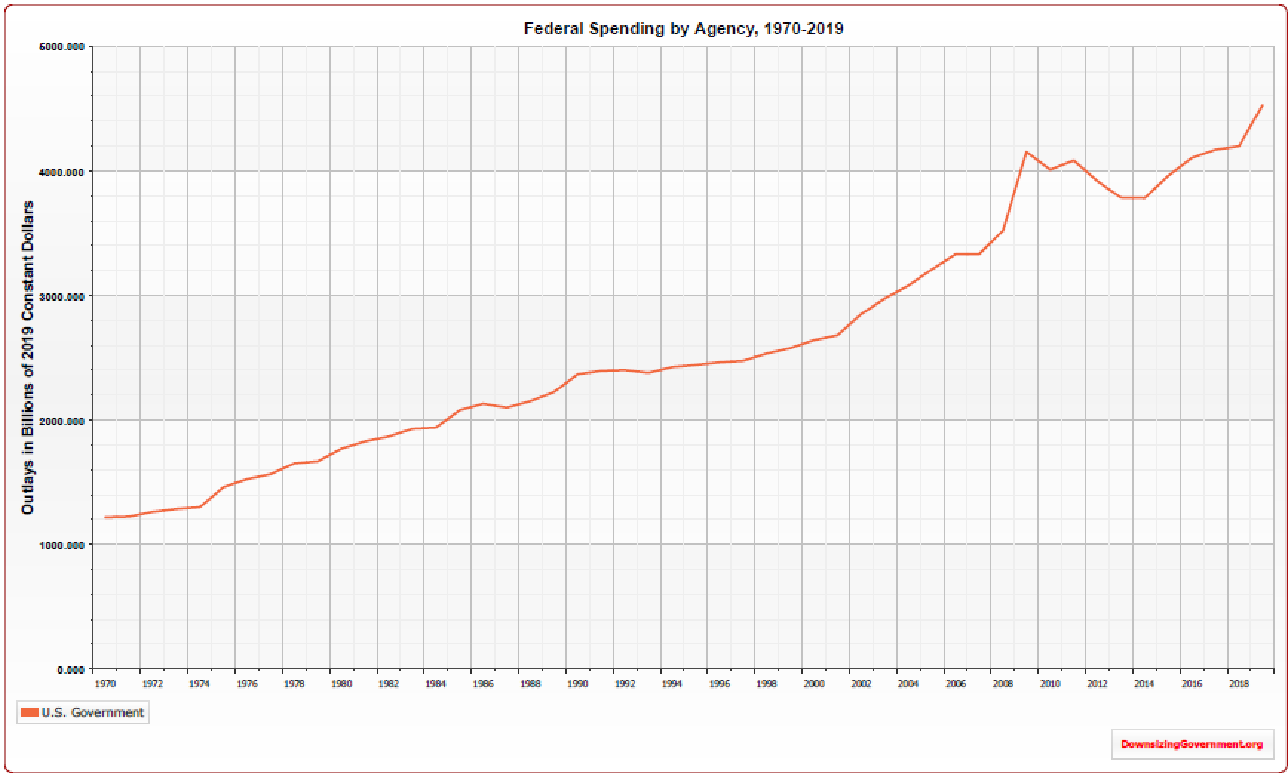

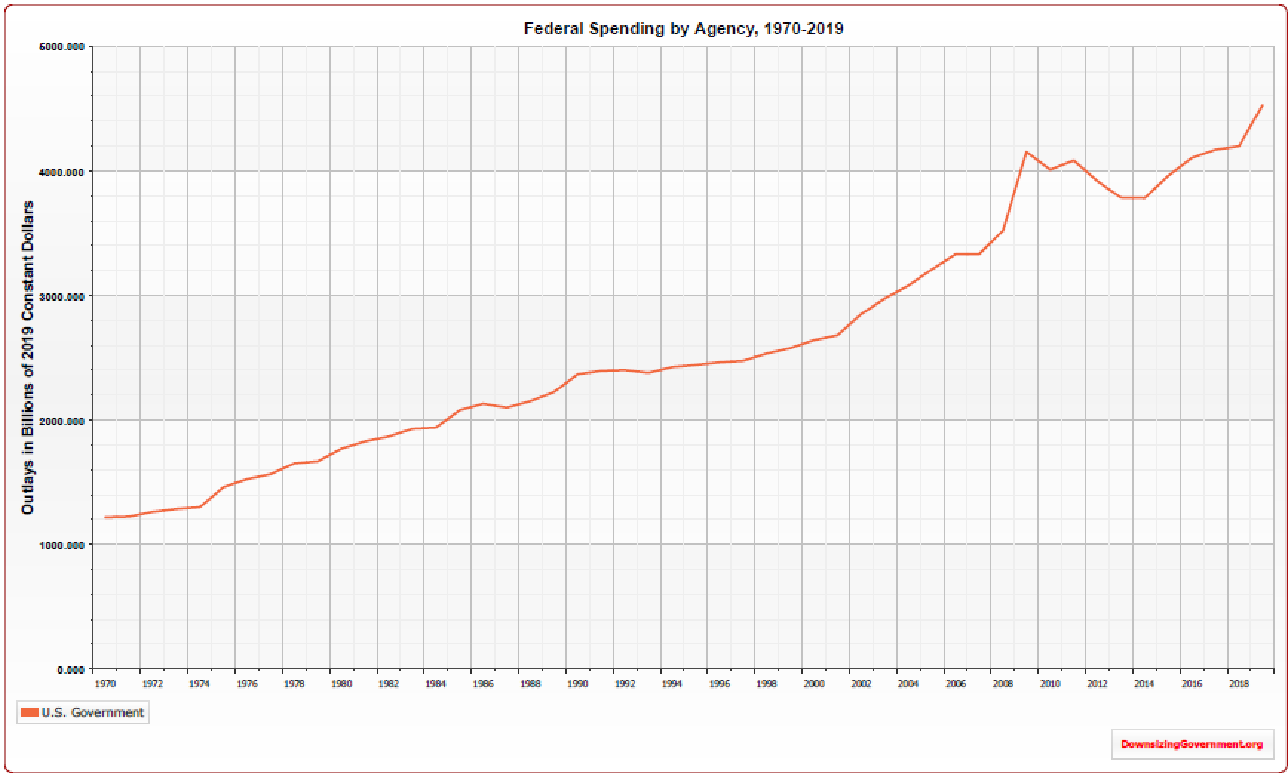

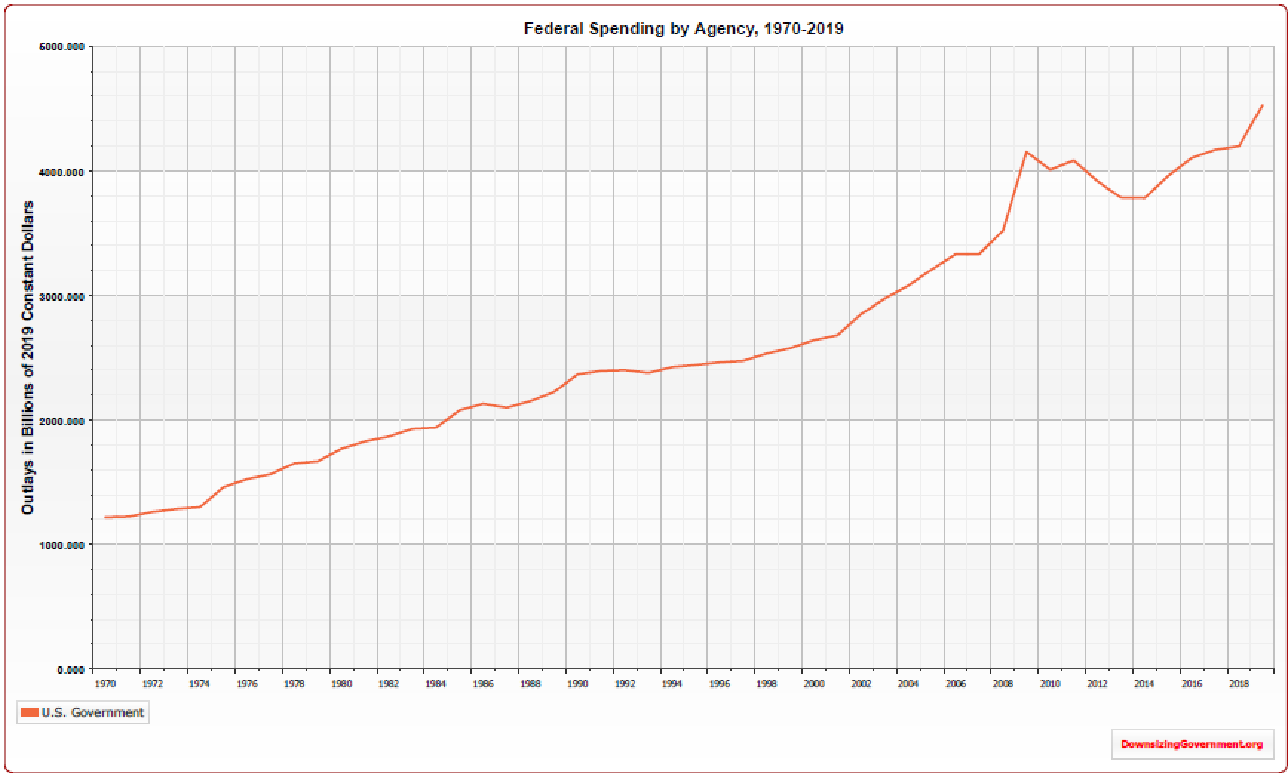

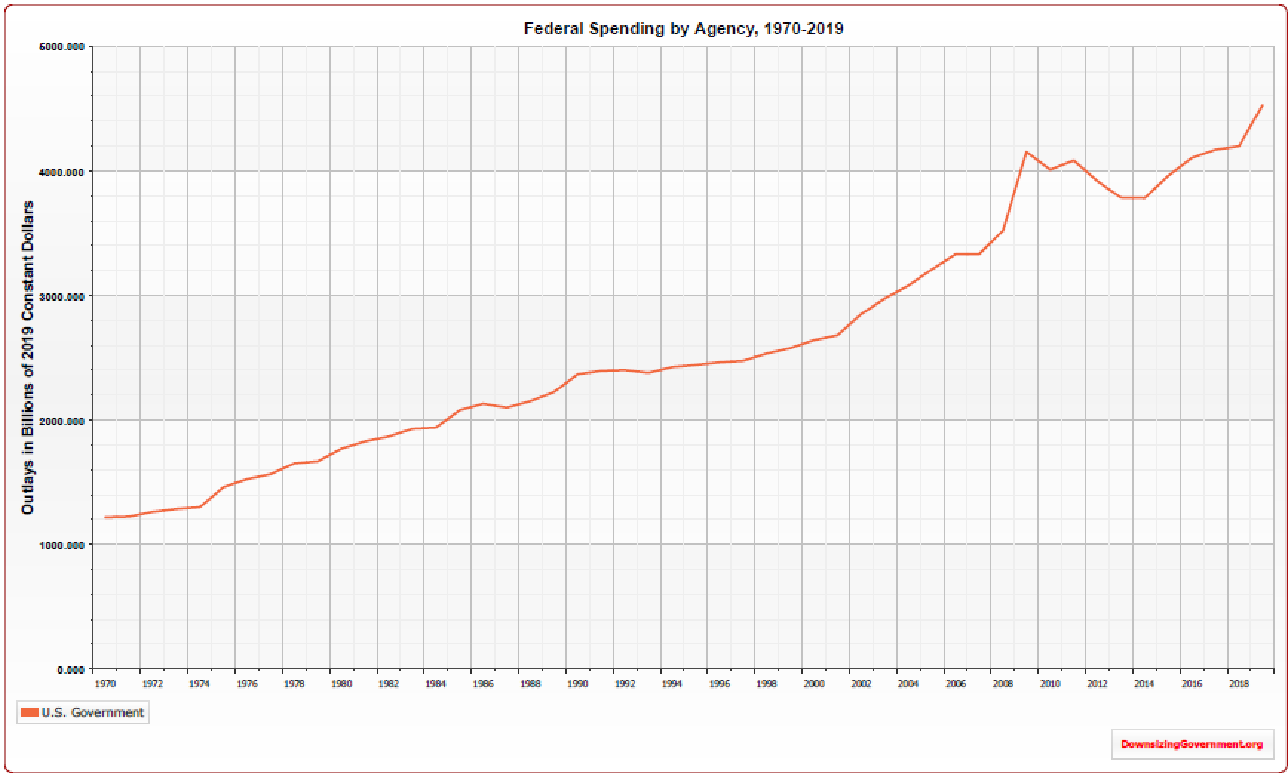

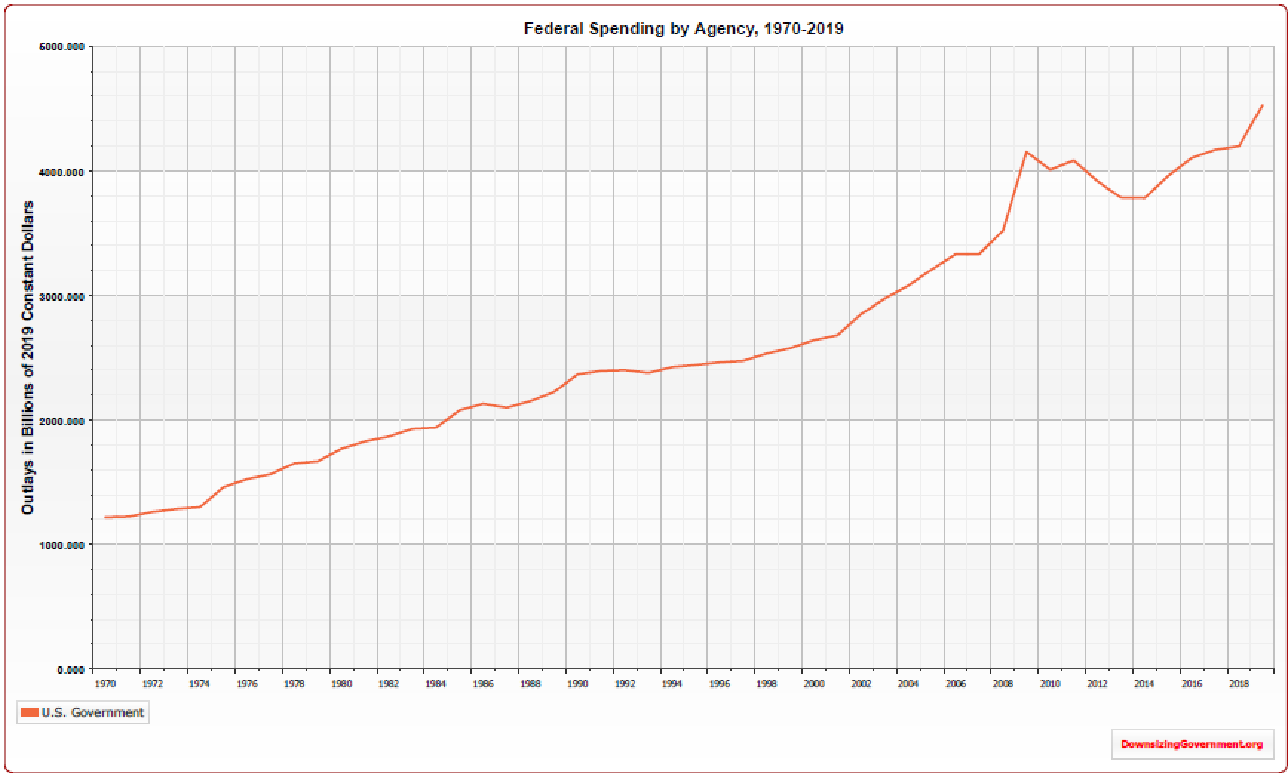

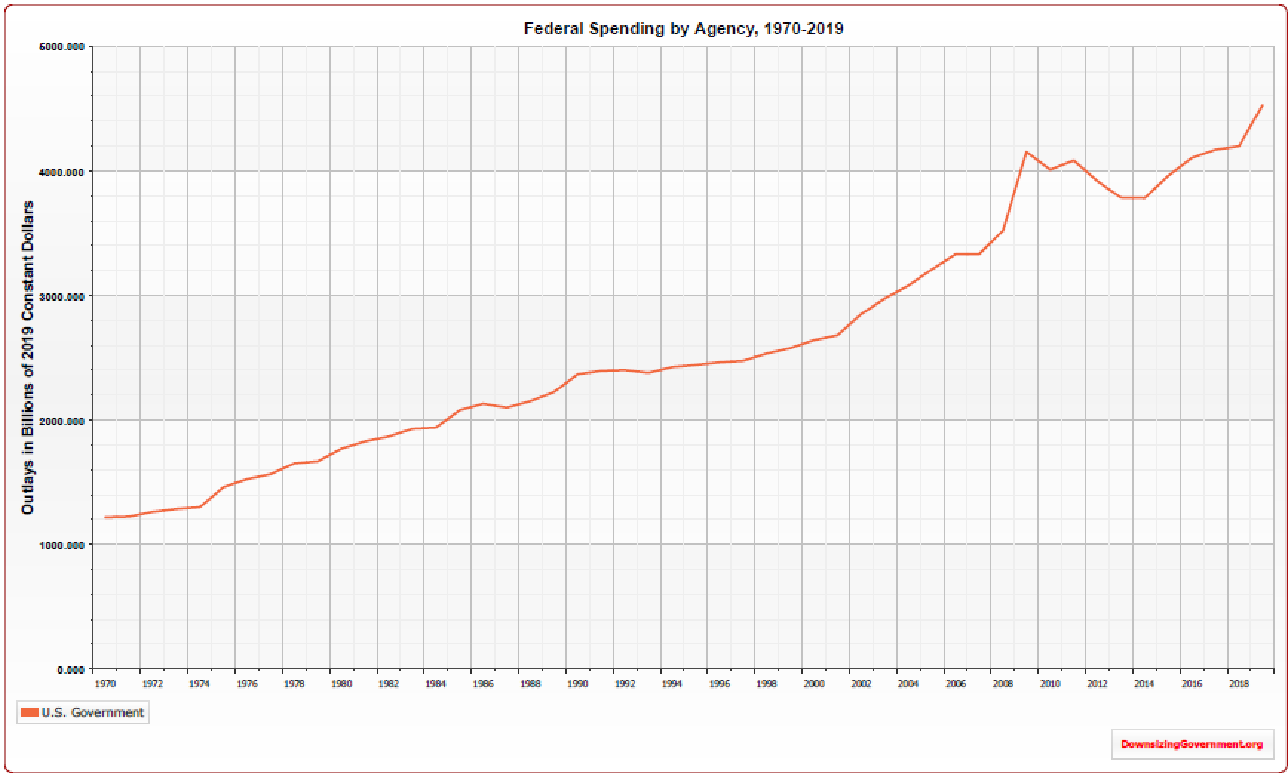

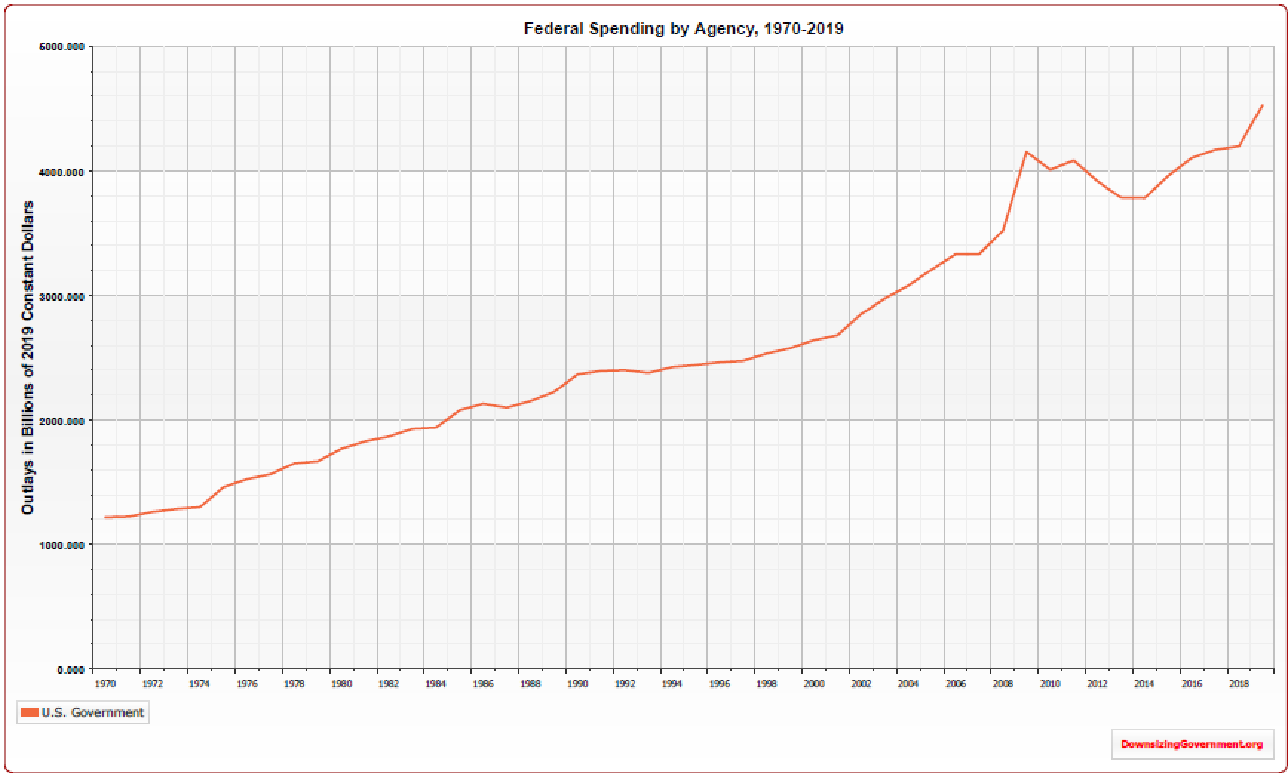

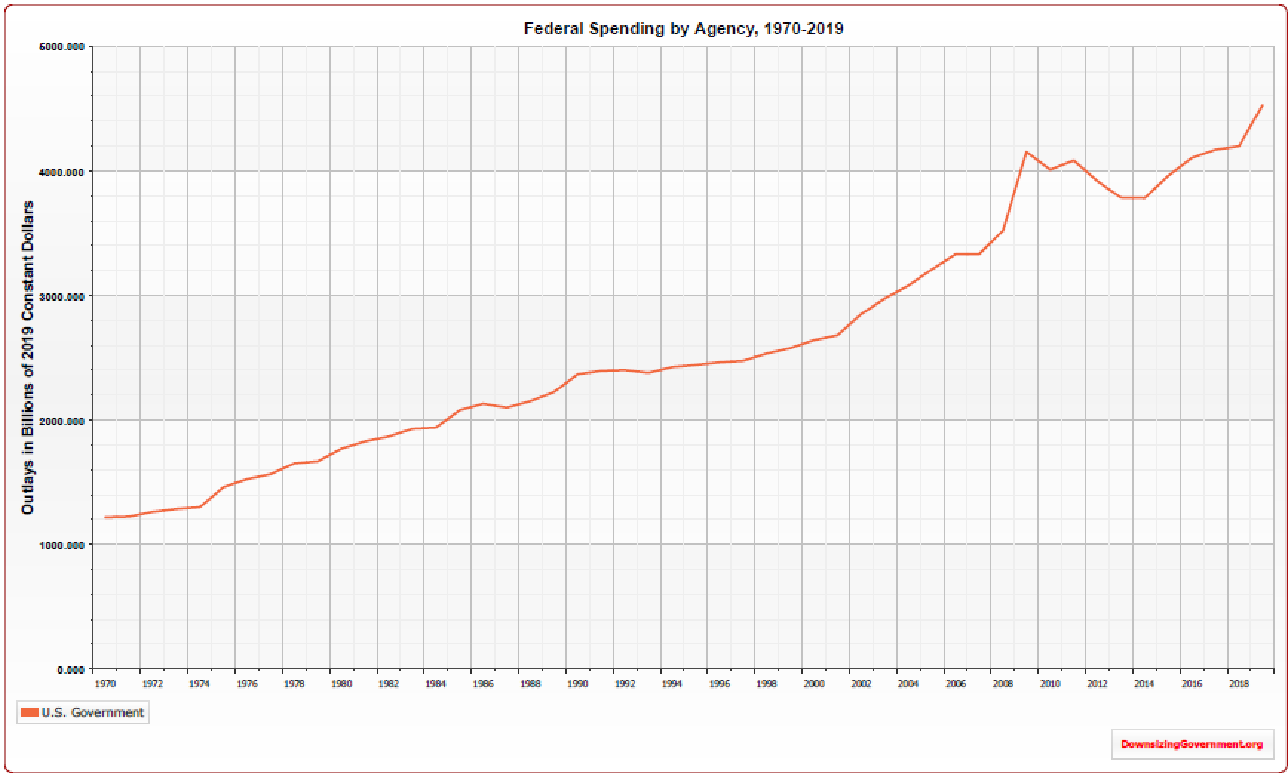

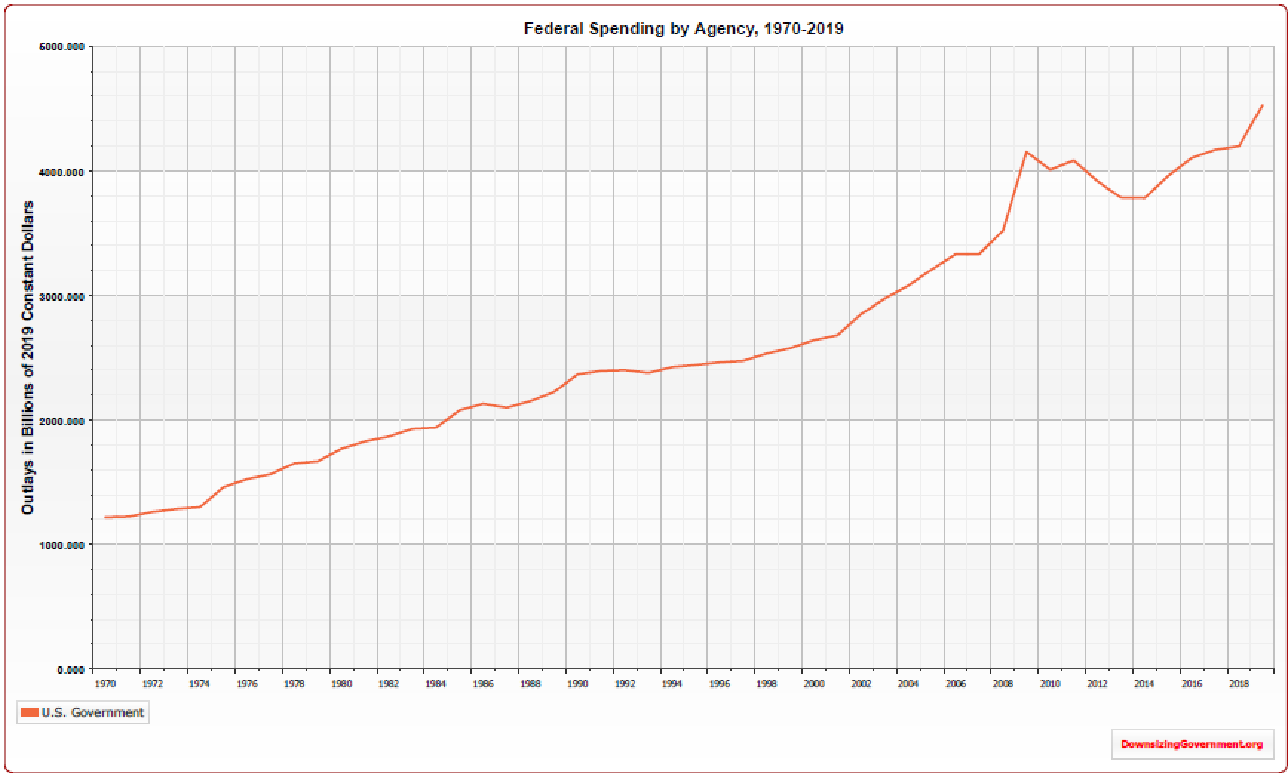

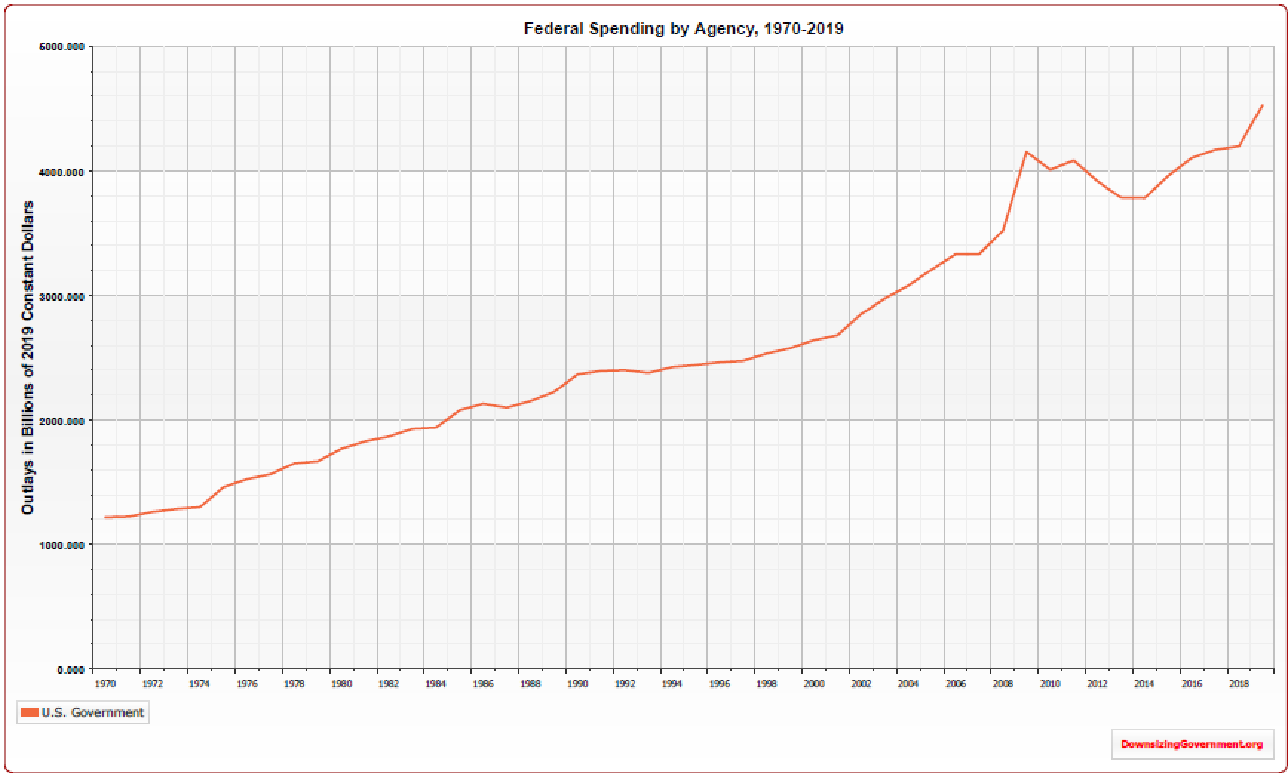

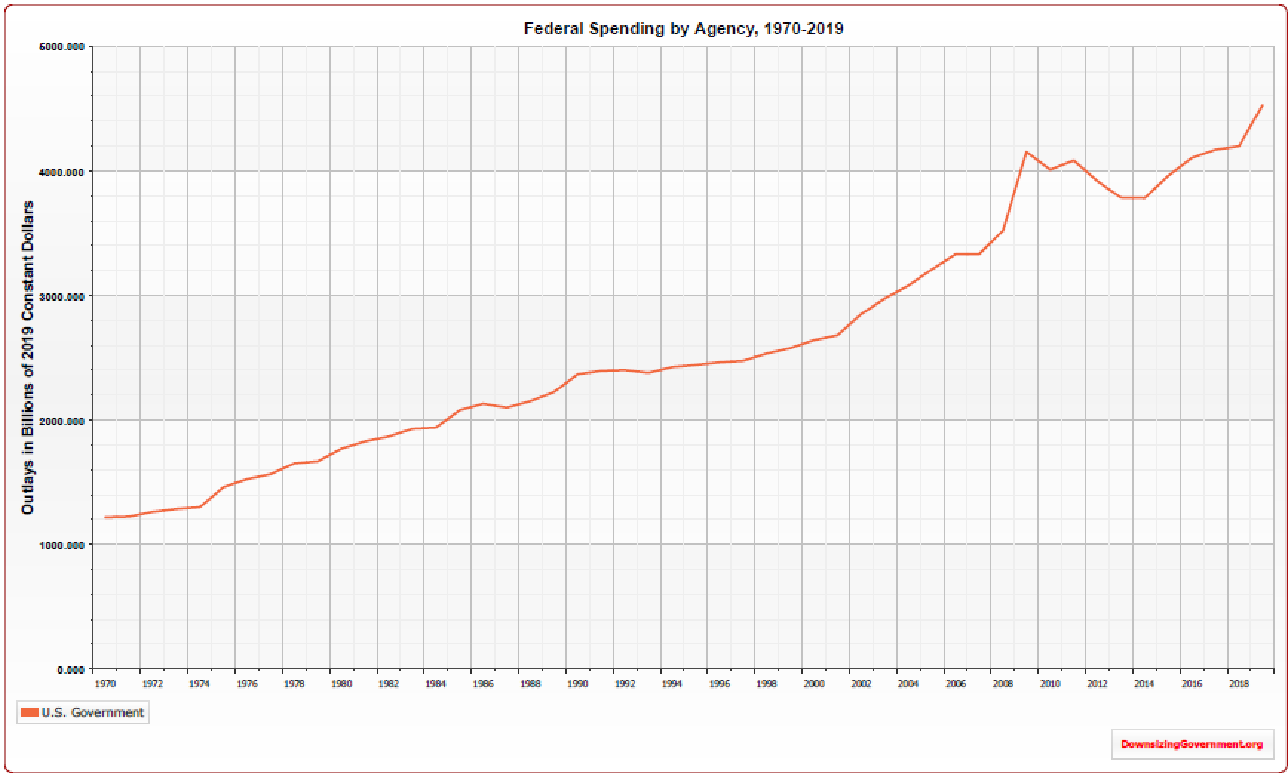

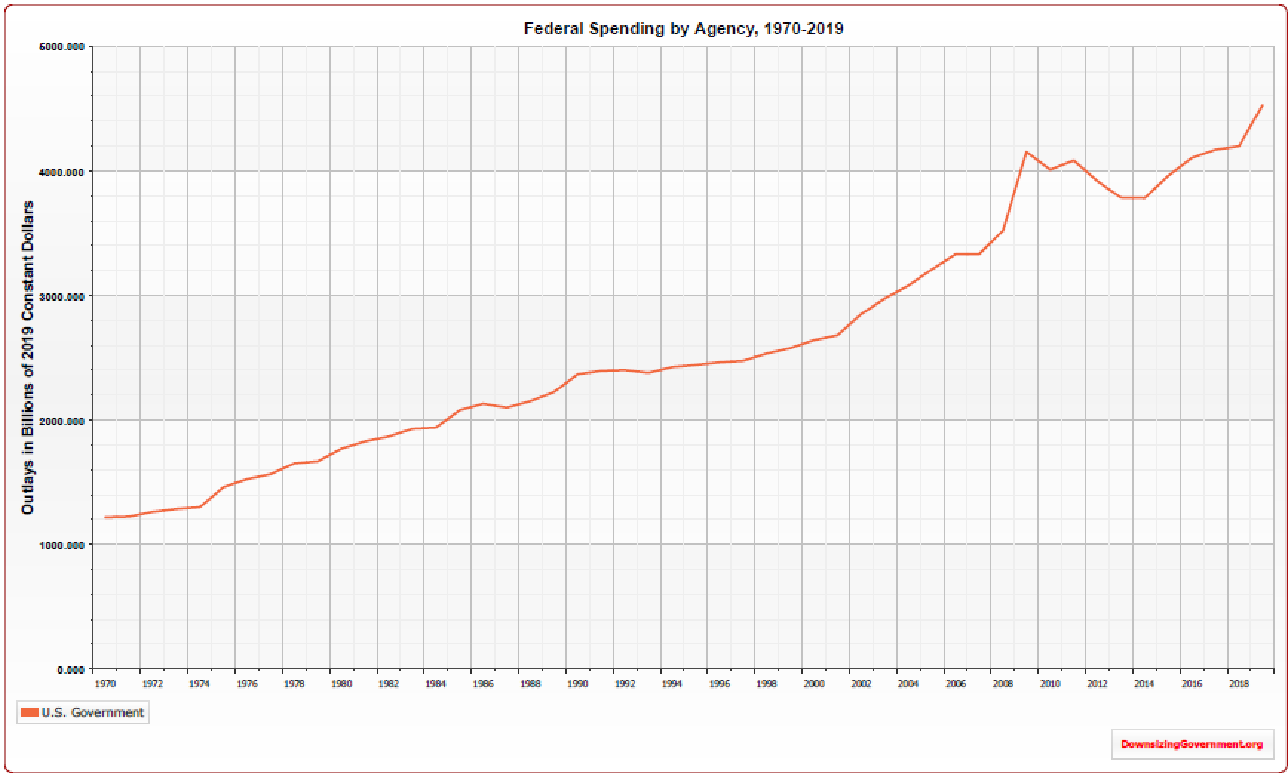

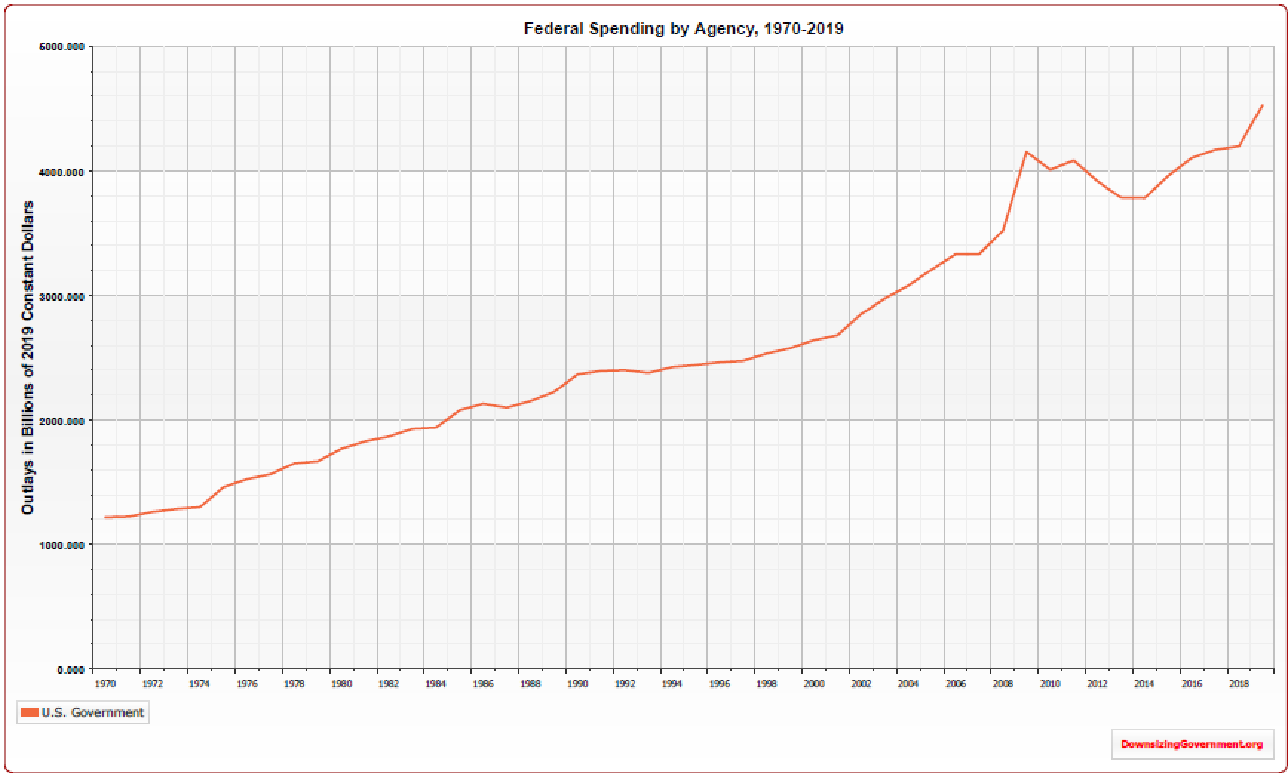

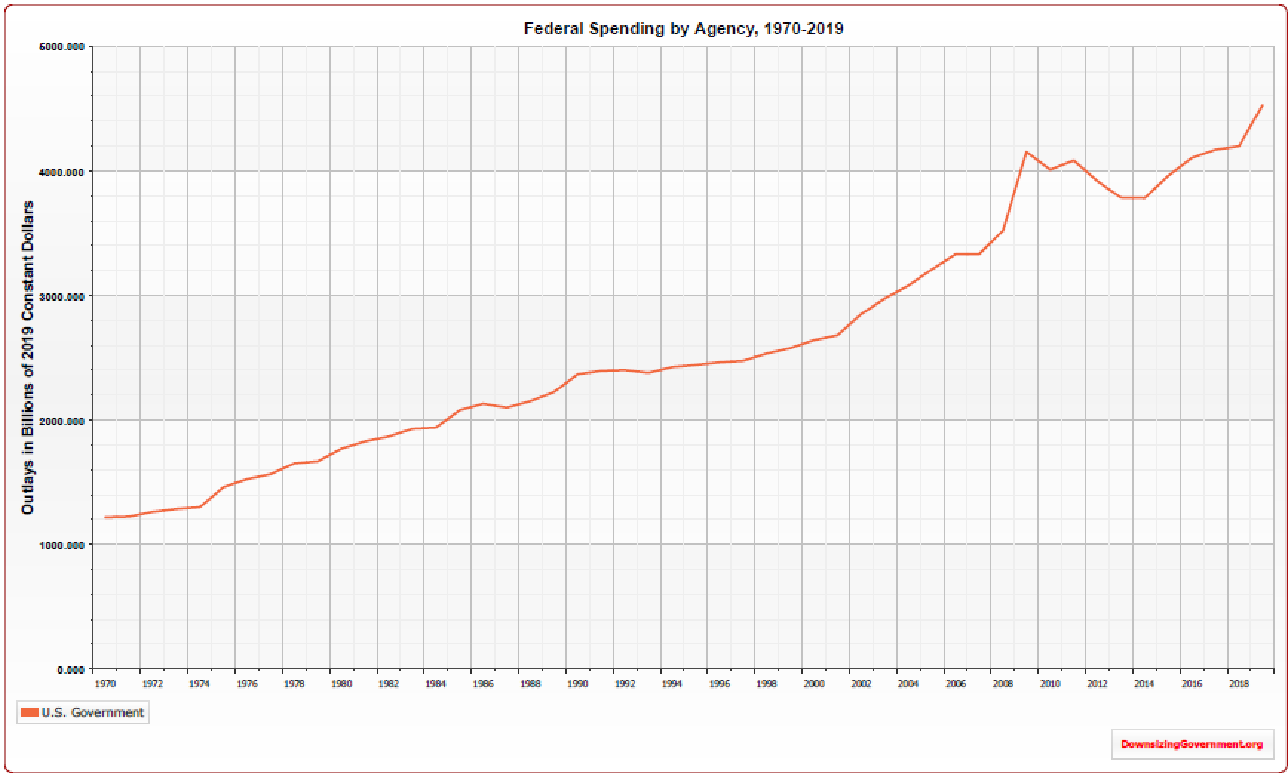

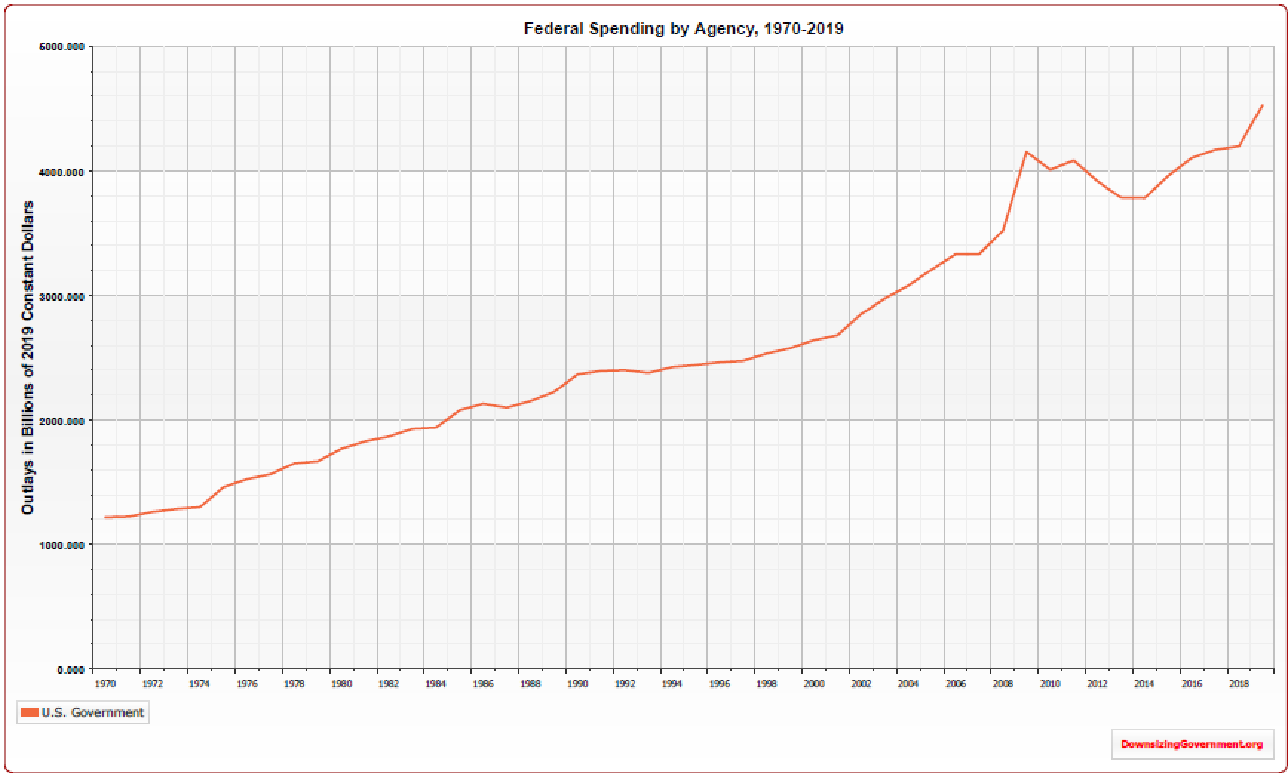

Let’s start with the U.S. budget and overall size of government. As can be seen from the charts below (courtesy of the Cato Institute’s Chris Edwards), inflation-adjusted government expenditures have grown steadily over the last several decades, while spending as a share of GDP has fluctuated but is still up since libertarians first “assumed control” of D.C. in the ’70s:

Most of this increase is driven by entitlements, which libertarians have of course been trying—mostly unsuccessfully—to reform for decades:

In terms of international comparisons, total U.S. federal spending as a share of GDP is larger than Ireland, Chile, Korea, Colombia, Switzerland, Costa Rica and Lithuania, and within a percentage point of Australia, Latvia, and Japan. In terms of just government health spending, the U.S. government spends more dollars per capita than, well, basically everybody:

Much of this spending is captured in the dramatic rise in federal subsidy programs between 1970 and 2015:

… and the tens of millions of Americans today receiving some form of federal support:

Then there’s the debt—another longstanding libertarian priority and one that, per the latest CBO figures, pretty much speaks for itself:

The Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget notes, moreover, that the United States actually “ranks number one among advanced economies in expected increase of debt as a percentage of GDP” and “has the highest deficits among advanced economies.” So very libertarian.

Now, one could argue that libertarians have been reasonably successful on taxes, but this “victory” is pretty hollow without concomitant changes in spending. Furthermore, while federal income tax rates have fallen, and the United States has a relatively low tax burden compared to the OECD average, “average-wage workers still pay about 30 percent of their wages in taxes” (a surprisingly consistent figure since 2000), and the system remains highly progressive. U.S. corporate tax rates also have fallen, but the most significant cut happened just three years ago and corporate taxes are falling everywhere. Meanwhile, U.S. corporate rates remain above the developed country average, and domestic corporations in 2019 still paid higher effective tax rates than their counterparts in Canada, Sweden, the United Kingdom and elsewhere.

Oh, and the federal tax code still clocks in at several thousand pages (roughly 4 million words) and remains exceedingly complex:

None of this screams “libertarian economics”!

Finally, the federal workforce is roughly the same size today as it was in 1981:

If this is libertarian control of Washington, I shudder to think of the alternative.

The administrative state.

Despite some prominent “libertarian” deregulation victories (airlines, telecommunications, banking, and transportation, for example), the regulatory state’s overall story is one of slow and continued expansion. The Mercatus Center’s regulation project provides one example, in counting just how long it would take a person to read the entire Code of Federal Regulations:

The Competitive Enterprise Institute provides another metric, in final rules issued in the Federal Register:

CEI adds that “[g]oing back to 1976, when the Federal Register first began itemizing them, 204,802 rules have been issued.” Other, more complex metrics find similar growth—and impact—of the administrative state.

This growth has been especially pointed at many of the agencies that libertarians most vigorously criticize, including but not limited to the FBI, ATF, DEA (and federal drug control programs), ICE, and the TSA:

Look at all that libertarianism! (You can make your own depressing chart here.) Spending growth (and mission creep) has also occurred at the government agencies most recently alleged to have been victims of libertarian fundamentalism—such as the FDA, NIH and CDC.

State and local government.

The long-term growth of spending and regulation, of course, is not limited to the federal level. As noted above, state and local budgets are up substantially as a share of GDP, and they’ve also increased in real terms:

… as have state and local regulations, especially for occupational licensing:

In the 1950s, approximately 5% of U.S. workers had an occupational license, meaning they completed additional schooling or training (and paid the necessary fees) and passed an exam to be licensed to practice the profession in a certain state. Today, the Bureau of Labor Statistics estimates that 23% of full-time workers have a license. (For comparison, fewer than 3% of workers in the U.S. are paid at or below the federal minimum wage and fewer than 11% of workers currently belong to a labor union.) This uptick in licensed workers is the direct result of the growth of occupational licensing laws. In the early 1990s, 800 occupations required licenses in at least one state. In 2016, that number increased to approximately 1,100 occupations.

And housing:

More recently, there have been some improvements in these and other state and local policy issues, but that’s hardly a sign of historical libertarian dominance (in fact, much the opposite).

Other issues.

One area that has arguably had a Libertarian Moment is the courts, but even there, the changes have been recent and—contrary to some claims—most definitely not limited to “libertarian economics” or social “libertinism.” As Luke Goodrich of Becket, a legal non-profit dedicated to religious liberty, recently detailed on Twitter, religious freedom is “on a massive, decade-long winning streak at the Supreme Court,” with advocates going a perfect 15-for-15 in religious freedom cases since 2011. By contrast, the court has been mixed (at best) on important administrative law issues—refusing, for example, to hear a “non-delegation” challenge to the absurdly vague “national security” law that let President Trump impose steel tariffs; and doing little (so far) to limit the courts’ longstanding deference to the bureaucracy. The court has also been flat-out bad on executive power, another libertarian priority.

Other “libertarian victories,” such as gay marriage, drug legalization, and criminal justice reform, have been similarly partial and recent—and coming after decades of movement in the opposite direction (i.e., during all that time Friedmanesque ideologues were running the country). Even then, plenty of work remains to be done—for example, the United States still has the highest incarceration rate in the world (due in part to the drug war), and our criminal code is so broad and complex that @CrimeADay can tweet for more than six years (and counting!) without doubling up. (And, of course, the agencies enforcing these laws are enjoying more and more funding.)

Oh, and did I mention all the land? So much land.

But the globalism.

Finally, there’s immigration and trade—where today’s economic nationalists focus much of their anti-libertarian scorn. Again, however, the common notion that globalist libertarians have been running the show dissolves under scrutiny.

On immigration, we’ll leave aside the fact that the biggest change to immigration law occurred five years before Friedman’s NYT essay was published (when restrictive quotas of the National Origins Act (NOA) were replaced by the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965). Even then, U.S. immigration levels are at historically normal levels—hardly where libertarians would like them and well below the levels of many other countries:

For example, the United States’ “net migration rate” is only high when compared to the aforementioned NOA period:

The same goes for per capita immigration rates:

U.S. immigration policy also isn’t generous by comparison to other countries (and don’t even get me started about Canada):

And finally, there’s the oh-so-libertarian path to getting a green card:

That brings us to Washington’s “free trade fetish”—probably the policy area most often cited by folks on the right as proof of libertarian economic domination. Yet, as I’ve written repeatedly, the notion that libertarians have been controlling U.S. trade policy for the last 40-plus years is manifest nonsense. Yes, Reagan in the ’80s talked a big game and certainly advanced trade agreements like NAFTA and the World Trade Organization, but he also implemented a lot of protectionist policies. too, reflecting the same messy, political, and pragmatic position on trade that subsequent U.S. presidents have generally taken. The result, as I explained on these pages a few months ago: some free trade wins (e.g., tariff rates and trade agreements), but a lot of losses too: “[S]ince the 1990s … the United States has continued to use tariffs and quotas to protect politically powerful sectors and has become a world leader in the use of non‐tariff barriers to achieve similar ends. The laundry list of such methods includes anti‐dumping and anti‐subsidy duties, intellectual property‐based import bans, ‘Buy American’ and other domestic procurement restrictions, export subsidies, technical regulations and licensing laws, shipping restrictions (the Jones Act), investment restrictions, and export licensing systems.” (In this regard, I recommend my Cato colleague Dan Ikenson’s new paper on the sordid history of U.S. anti-dumping policy.)

The same goes for China—a subject we’ll cover in greater detail soon. As detailed in my recent (and lengthy!) Cato paper on the subject, the U.S. government’s economic engagement with China in the ’90s and 2000s—while certainly supported by many libertarians at the time—wasn’t driven by free trade ideology or naïve hopes for Chinese democratization. Instead, it was a slow, bipartisan process with pragmatic foreign policy and commercial motivations; it came in response to decades of Chinese economic liberalization; and it was accompanied by hundreds of U.S. restrictions on Chinese imports, as well as subsidies to affected companies and workers—measures that libertarians often opposed.

Indeed, when the independent Global Trade Alert ranked all protectionist measures—not just tariffs—imposed between 2008 (when the group first started keeping track) and 2017 (when Trump came into office), guess who came in first? Yep:

Finally, there’s the fact that the United States remains one of the least “open” economies in the world. For example, the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco found in 2019 that only about 11 percent of U.S. consumer spending can be traced to imported goods—a “nearly unchanged” ratio over the past 15 years. According to the World Bank, moreover, the United States in 2019 ranked dead last among surveyed countries in terms of trade (imports and exports of goods and services) as a share of national GDP—26 percent, right below Sudan and Cuba (27 percent) and also well below China (36 percent), Japan (37 percent), South Korea (77 percent) and Germany (88 percent) and the world average (60 percent). We ranked fifth-lowest (14.7 percent) in terms of import shares, again below China (17.3 percent), Japan (18.3 percent), South Korea (36.9 percent), Germany (41.1 percent) and the world average (30%). Other, more sophisticated analyses of trade openness show the same thing.

So much for all that globalism.

Summing it all up.

Various independent analyses of economic freedom generally reflect the trends above: today the United States ranks sixth overall in the Fraser/Cato Economic Freedom of the World report (down from second in 1980); sixth overall in the World Bank’s Doing Business Report (down from first in 2004); and 17th in the Heritage Foundation’s Index of Economic Freedom (down from fourth in 1995). Each of these reports shows similar things: (1) strong and consistent U.S. performance in systemic areas like property rights and rule of law, but middling scores on the issues—trade, taxation, business formation, fiscal health, etc.—where “libertarian economics” would have the largest impact; and (2) other countries’ more consistent embrace of freer markets in recent years. (Maybe their libertarians do control things.)

None of this is to say, of course, that “libertarian economics” has been meaningless in Washington. Beyond the aforementioned victories (and others), it’s possible—if not likely—that things would be even worse without strong, consistent, and vocal advocates for free markets and free people. But all of the above should put to bed the silly idea that “libertarian economics” have been driving the U.S. policy bus since Friedman’s essay first graced the Times’ pages 50 years ago. Instead, U.S. policy over this period has ebbed and flowed from more limited to more expansive state intervention (and back again), while government overall has slowly crept ever bigger—much to libertarians’ chagrin. There have been some clear free market victories, some clear losses, and a lot of bureaucratic inertia and partisan politics in between. Many of those victories, moreover, have come not from an idealistic embrace of Friedman and Hayek but instead as a reluctant, kludgy response to decades of failed alternatives or due to non-economic (e.g., foreign policy) factors.

But overall, our current, mishmash system reflects the divided and often frustrating mix of views and procedures that is the United States. That reality is far more complicated (and boring) than the populist caricature, and it certainly doesn’t lend itself to easy solutions like purging Friedmanesque ideologues from the government. But it’s nevertheless true. And the sooner we acknowledge this reality, the sooner we can grow up and get to work on making it better.

Chart of the Week

The links.

I’ll see your Taco Bell wine and raise you a DewGarita

Photograph by George Rose/Getty Images.

Correction, September 22, 2020: This post originally misspelled Kurt Andersen’s surname.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.