One of the difficulties in writing an almost-weekly newsletter is that topics you want to cover, but aren’t necessarily BREAKING NEWS, can often fall by the wayside as newsier priorities emerge. (Incessant U.S. tariff stuff has obviously compounded this issue for Capitolism.) California’s high-speed rail system has long fallen into this category, as its problems are both well-known and well-covered (and the butt of libertarian jokes everywhere). But the project was again in the news recently, with fresh details that even I found astounding (and infuriating).

It's a classic example of how big government projects can go horribly wrong and still stay afloat, wasting untold resources along the way.

Catching Up With California High-Speed Rail

On the leaderboard of government boondoggles, California’s high-speed rail system must surely rank near the top. As Cato Institute analyst Marc Joffe documented in 2023, California voters first approved a $10 billion bond for the project in 2008, with the understanding that zippy service between Los Angeles and San Francisco would begin in 2020 at a total cost of just $33 billion. Three years past that deadline, however, the project had ballooned in both scope and cost, while not a single piece of track had been laid—even though state, federal, and local taxpayers had already spent at least $13 billion on the project:

Since then, the news has only gotten worse. The cost estimate has now been upped to $135 billion—more than $100 billion higher than the original proposal!—and, as the Associated Press reported in late April, the CEO of the California High-Speed Rail Authority (CHSRA) said it might take two more decades to complete “most” of the San Francisco-to-Los Angeles segment.

Even this schedule, however, is almost certainly too optimistic. As the AP notes, the only construction underway now is for a 119-mile stretch in California’s Central Valley, but only 22 miles will be ready for track-laying next year and, per the Reason Foundation’s Bob Poole, another 52 miles haven’t even begun construction because “CHSRA did not meet the deadline for having the final configuration footprint completed by the end of 2024” and “the agency still needs to reach agreements with 12 of the 38 local agencies and utilities on utility relocations.”

Once the line is built, Joffe adds, recent experience with other U.S. rail projects indicates that more delays are likely because of necessary safety testing, new technologies being deployed for the first time in the United States (e.g., 200 mph trains), and infrastructure that will be at least a decade old when things finally get running.

Future funding is another big problem. As the AP notes, the project has thus far been funded by a voter-approved bond, revenues from the state’s cap-and-trade program, and federal subsidies. However, “The state is now out of bond money,” and there are “new fears that the Trump administration could pull $4 billion in federal funding.” Indeed, as Poole recently detailed:

[T]he rail authority received a letter from Kyle Fields, chief counsel of the Federal Railroad Administration (FRA) informing it that FRA is about to initiate a review of the CHSRA’s compliance with FRA-administered grants to the project. Per the letter, FRA completed its annual monitoring review in October. It identified six areas of interest and said that “FRA intends to seek additional information to evaluate CHSRA’s performance and ability to perform under FRA-administered funding agreements.” The letter also noted that “the compliance review and resulting findings may result in remedial action up to and including withholding of reimbursement and termination of cooperative agreements.” And finally it warned that “any work completed from the date of this notice forward is at the risk of CHSRA.”

As Poole explains, the CHSRA is today hoping that private investors will supplement public funds and help rescue the project, but it’s hard to see why any private investor would make that bet with so little clarity about future public contributions and huge questions about future ridership (and thus farebox revenue and related economic activity in surrounding neighborhoods). Indeed, as Joffe noted in 2024, ridership on the Central Valley segment—and thus revenues generated therefrom—will likely underwhelm “because Central Valley cities lack highly concentrated downtowns and dense local transit networks” and a rider would save only 60-90 minutes by taking the train instead of driving. Overall, he speculates, “Ridership will almost certainly not reach the California High-Speed Rail Authority’s optimistic projections and, as a result, the line will likely produce operating losses in contravention of the ballot language that authorized bond funding of the project in 2008.”

The completed line from San Francisco-to-Los Angeles would likely face similar concerns, given its recent redesign. As the AP notes, the CHSRA’s new plan is to connect towns on the outskirts of both major metros—Gilroy, about 70 miles southeast of San Francisco, and Palmdale, 37 miles northeast of Los Angeles—instead of the city centers. That surely saves construction time and money, but it means that riders will need another hour or more to get into the cities. All told, economist (and Californian) Scott Sumner estimates that this new setup would require a seven-hour series of trains for someone to get from downtown San Francisco to downtown Los Angeles, instead of the three-hour, one-train trip that voters were originally promised. He thus speculates that “almost no one” will use this system because it’d be so much cheaper and easier to fly. (And by the time 2045 rolls around, there would surely be driverless cars—and who knows what else—available too.)

Put it all together, and you can see why, per the AP, critics believe the project “will never be completed” and will instead leave dozens of “towering and unusable” structures—underpasses, viaducts, bridges, etc.—behind.

How Did This Happen?

As Joffe documented in a 2024 paper, public intercity rail and transit projects routinely incur costs that far exceed the revenue they take in and, in many cases, the value they provide to states and localities. And other government-managed and subsidized rail projects in the U.S. suffer from similar afflictions.

Nevertheless, the California system is effectively a textbook case of how and why so many grandiose public projects fail.

Start with the politics. As the New York Times documented in 2022, California’s rail map was repeatedly altered to appease politically powerful individuals—especially government officials—who would personally benefit from the changes, even though the project itself would be radically different from what California voters approved and would face higher costs and long delays:

Political compromises, the records show, produced difficult and costly routes through the state’s farm belt. They routed the train across a geologically complex mountain pass in the Bay Area. And they dictated that construction would begin in the center of the state, in the agricultural heartland, not at either of the urban ends where tens of millions of potential riders live.

…

Collectively, they turned a project that might have been built more quickly and cheaply into a behemoth so expensive that, without a major new source of funding, there is little chance it can ever reach its original goal of connecting California’s two biggest metropolitan areas in two hours and 40 minutes.

The section now under construction in the Central Valley may have been the worst such “compromise.” As the Times details, it “quickly became a quagmire” because it required “the largest land take in modern state history” and those “seizures have involved bitter litigation against well-resourced farmers, whose fields were being split diagonally.” Adding insult to injury, “Federal grants of $3.5 billion for what was supposed to be a shovel-ready project pushed the state to prematurely issue the first construction contracts when it lacked any land to build on”—a move that “resulted in hundreds of millions of dollars in contractor delay claims.”

Other litigation surrounding the proposed route has imposed additional costs and delays. Over the last several years, plaintiffs have challenged various aspects of the project under various state and federal environmental laws, including the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA), the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), and the Endangered Species Act; the original ballot measure approving the project (Proposition 1A); California’s public records act; local land use laws; and more.

Government regulations—many of which were tied to state and federal involvement—have compounded the costs and delays. Beyond the well-covered problems with environmental permitting under both CEQA and NEPA, there are Buy American rules that require federally funded transportation projects to use domestically produced materials, equipment, and finished goods. As we’ve discussed, these products are often more expensive and less innovative than foreign alternatives—if they’re available at all—and require participating contractors to spend needless time and money on regulatory compliance instead of their actual business. In the case of high-speed rail, Buy American rules are particularly absurd because there is literally no train manufacturer in the United States building anything that can run at the high speeds California’s project needs. Thus, both Amtrak and CHSRA have been left to “hope” that their combined, top-dollar order “would be attractive enough for international manufacturers of high-speed rail equipment to commit to building trains in the U.S. as required by the federal government’s Buy America laws.”

Political uncertainty is another problem, as both funding and project continuation are always at risk of being yanked by the next election—a risk that is materializing now with Donald Trump back in office. Doubts are also increasingly being raised by California lawmakers as to the project’s costs and viability, yet, as Joffe documented last year, governments “continue to provide enough money to keep the project going without providing a path to completion.”

Great business model.

How Does This Keep Happening?

Although the size and scale of California’s failure are eye-opening, most of the project’s problems and root causes are typical of large-scale government projects in the United States. Scroll through my Cato paper on the impediments to effective U.S. industrial policy, for example, and you’ll find that many of the same things thwarting California’s high-speed rail system—political meddling, bad modeling, costly/conflicting regulations, etc.—have done the same to federal projects since at least the 1960s. Indeed, as Matt Welch documented a few years ago, the California-based Reason Foundation predicted the high-speed rail disaster all the way back in 2008, with its experts then calling the project “a money-grab for local governments and transportation authorities," based on “wildly exaggerated claims” of cost and ridership compared to contemporaneous analyses by independent experts.

That the rail project continues to limp along, wasting billions of dollars and finite resources, raises the obvious question of why these projects keep getting approved—and keep getting funded long after their costly infeasibility has been made abundantly clear. And the reasons are also textbook stuff.

Most obviously, there’s the good ol’ sunk cost fallacy, which keeps people from ditching an obvious failure because of the time and money they’ve already spent on it. As Welch showed, moreover, a lot of public support for high-speed rail over the years has stemmed from irrational political and media optimism about the project—and about the government’s ability to complete it without all the usual problems—even after those issues once again materialize. Support has also been driven by ridiculous-in-retrospect “expert” estimates of cost and timing that routinely failed to account for all the typical things—politics, regulation, litigation, etc.—that accompany literally every large-scale government project initiated in the last few decades. (Something definitely not limited to transportation or infrastructure.)

Finally, there’s politics, which—as Sumner notes—made the project less about moving Californians from L.A. to San Francisco and more about moving rents (jobs, money, etc.) from taxpayers to powerful constituencies (emphasis mine):

In a sensible world, the authorities would have figured out a plan before starting construction. At some point they would have discovered that the project was infeasible, and abandoned the idea. But the actual goal was not a high-speed rail line; it was funding lots of contracts building high-speed rail lines. That project has succeeded. For the contractors, Palmdale to Gilroy is just as good as LA to San Francisco. Thus they decided to immediately begin constructing the line in order to present “facts on the ground” that would make it less likely that the project was abandoned. To be clear, on a cost/benefit basis it still makes sense to abandon this project, even after $13 billion has been spent, because the actual costs will undoubtedly vastly exceed the current $100 billion estimate.

As one critic told the AP, in what amounts to a hilarious understatement, “It doesn’t seem to me like the state government is in a hurry to finish it.” Yeah, well, of course it isn’t.

Sumner also hits on the last big issue keeping this boondoggle (and others like it) afloat: Once funds start flowing, it’s very difficult to stop them because new constituencies that profit from a project will inevitably fight like hell to keep the gravy train (pun!) going. Poole notes, for example, that the latest financial challenges to the California project have put the U.S. High-Speed Rail Coalition—“an alliance of 50 leading companies and unions from across the American high-speed rail industry” that all profit from these projects—on high alert. The organization, in fact, is “going to war to protect the Calif. project” and “plans to lobby in favor of CHSRA continuing to receive 25% of the proceeds from California’s cap-and-trade system, which has been providing about $1 billion per year to CHSRA.” Good luck fighting that.

Back in 2022, the New York Times summed up the situation well, calling the California project “a case study in how ambitious public works projects can become perilously encumbered by political compromise, unrealistic cost estimates, flawed engineering and a determination to persist on projects that have become, like the crippled financial institutions of 2008, too big to fail.” Three years later, the description unfortunately remains accurate.

The Private Alternative

None of this means that there’s no market for intercity rail in the United States, but it does show why we should be skeptical of grandiose, government-led projects that offer low costs and amazing, rapid benefits. In fact, while California’s rail project has been an unmitigated disaster, a smaller, private line in Florida shows that high-speed rail can be done here when it makes economic sense and state involvement is minimized.

Launched in 2023 and now shuttling people between Orlando and Miami at up to 125 mph, the Brightline rail project cost just $5 billion and took about 10 years to complete, despite numerous setbacks (including the pandemic). Assuming California’s system is completed by 2045 as now claimed (a big assumption!), Brightline will travel 61 percent as far, yet be completed in just 27 percent the time at a measly 4 percent the cost. That’s just crazy.

Brightline succeeded where California failed for two big reasons (beyond Florida’s easier regulatory environment). First, and as the AP noted at the time of launch, “Brightline is privately owned and seeking a profit.” This means the company was “more sensitive to getting the project completed quickly to save money,” and its investors were more sensitive to the project’s feasibility because it was their money on the line. As a private, for-profit entity, Brightline also can charge market rates for tickets and amenities, meaning revenues that are more likely to exceed costs, and—because it freely competes with other forms of transportation—will constantly be looking for ways to improve the already-nice customer experience. (“I didn’t meet a passenger who complained about the ride,” New York Times architecture critic Michael Kimmelman said last month.). As of today, the line is still losing money, but ridership is way up, with almost 3 million passengers last year.

And, of course, it’s actually operating—unlike in California.

Second, Brightline’s Florida project abstained from government funds. This meant it was “more insulated from politics” and could “plan a maximally efficient line, rather than, as California did, one that touched as many counties as possible.” It also meant that Brightline wasn’t subject to costly political conditions (e.g., social policies or union mandates). This includes Buy American mandates: While California had to jump through all sorts of ridiculous protectionist hoops, Brightline was free to “import materials from Siemens, a German company” and generally to “use the most cost-effective inputs—and to avoid expensive compliance mandates—mak[ing] their construction work cheaper.”

To be clear, this isn’t just a California problem: Brightline’s other project connecting Las Vegas and L.A. took government money and is now bogged down in Buy American rules, organized labor demands, politics, and "lobbying fights" over federal contracts. By September 2024, the project’s promised completion before the 2028 L.A. Olympics was in doubt because of Buy American-related litigation over which (foreign!) company will provide trains for the project. Now, its best-case scenario is completion by the end of 2028, months after the Olympics conclude.

Anyone wanna bet on whether the new deadline is met?

Summing It All Up

So, high-speed rail is possible in the United States—at least when it’s initiated, funded, and managed by the private sector—and California’s non-system is a textbook example of how and why government projects can go (and keep going) wrong. However, because it’s unlikely that future intercity rail and other transportation projects will go fully private (alas!), Joffe provides a handy list of recommendations to improve outcomes where government dollars are still involved. This includes commissioning an independent cost-benefit analysis prior to offering government grants or other taxpayer support; eliminating legal barriers—environmental permitting/litigation, Buy American mandates, etc.—that confound these projects (or, at the very least, exempting them from current restrictions); and forcing passenger rail services to rely mainly on farebox and related revenues to encourage operators “to think more like managers of a business rather than as political actors” who have non-economic objectives like maximizing jobs, votes, and subsidies.

Implementing these and other reforms won’t prevent future boondoggles entirely, but they would surely reduce the size and scope of the failures that still occur. And that’d be a heckuva lot better than what’s still, insanely going on in California today.

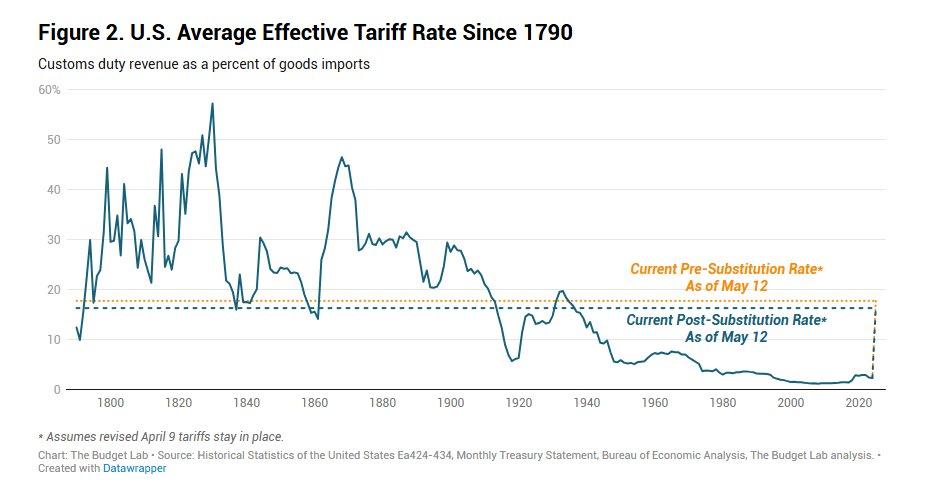

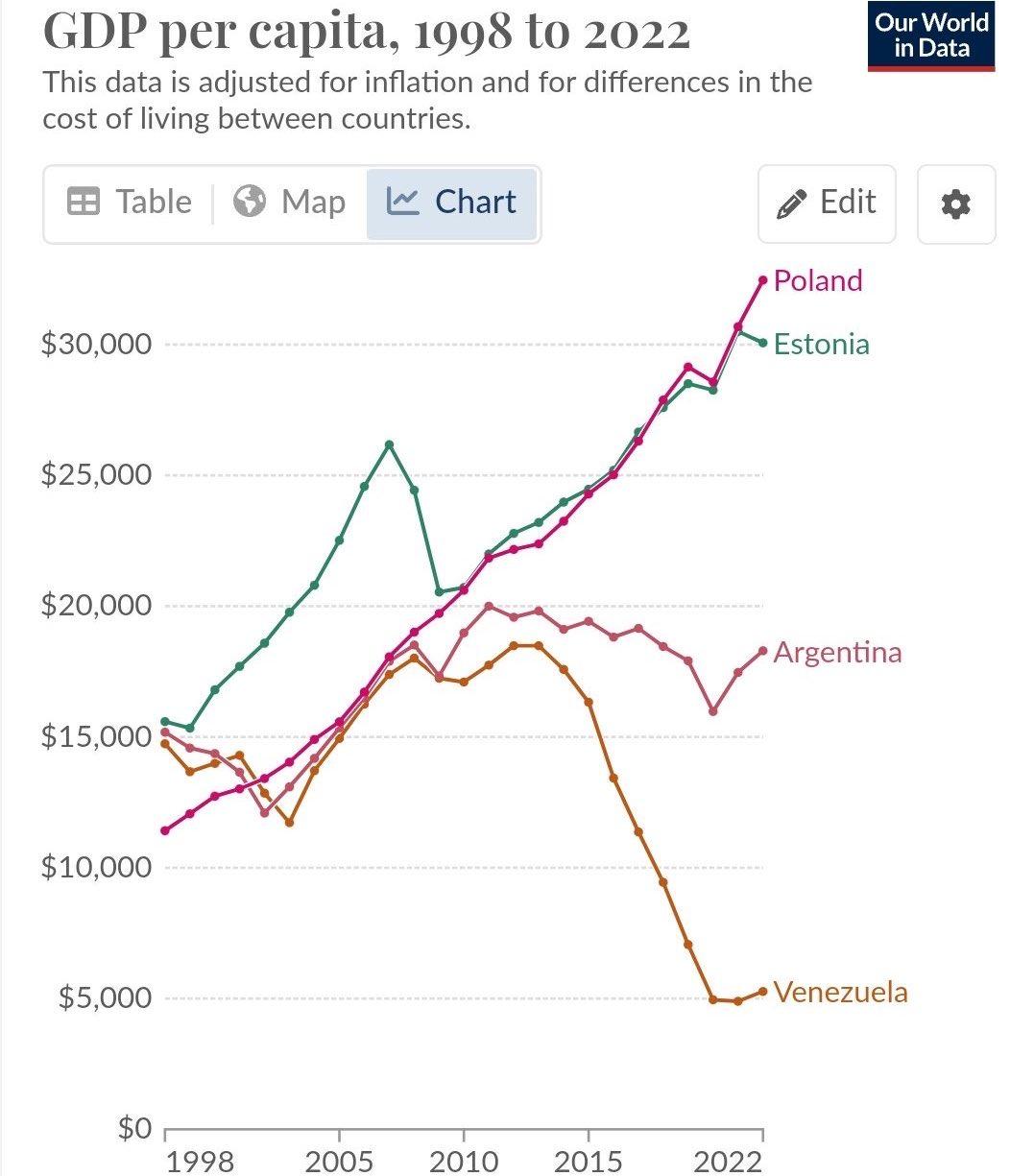

Chart(s) of the Week

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.