Dear Capitolisters,

Saturday, December 11, will mark the 20th anniversary of China’s accession to the World Trade Organization, and boy are some people upset about it. In particular, a bipartisan chorus of politicians, think tankers, and presidential advisers look at China’s recent and obvious economic, foreign policy, and human rights offenses, and point fingers not at Beijing but inward at the U.S. policymakers who decades ago backed China’s WTO entry and passed a law granting “permanent normal trade relations” (PNTR) the year prior. (PNTR was necessary for the U.S. to enjoy the benefits—e.g., better market access—of China’s WTO accession.) These events, so the story goes, fueled China’s rise and the now-famous “China Shock”—the period between 1999 and 2011 in which increased Chinese imports supposedly destroyed millions of American jobs—and today call into question not only the WTO “mistake,” but also the “neoliberal economic consensus” (especially free trade) that allegedly undergirded it. Since those darned neoliberals got China so wrong, critics argue, we must abandon traditional U.S. positions on China and on U.S. trade agreements, industrial policy, labor policy, and government economic intervention more broadly.

It’s a straightforward political story, but—like most straightforward political stories—it suffers from several historical, economic, and factual flaws, which combined render the narrative pretty useless (as a policy matter, at least). Even worse, it risks embracing new U.S. policies that “fix” a “problem” of limited actual import and that would probably make things worse, not better, for the United States and the world. And since I wrote a very long and boring paper on much of this last year, that’s what we’ll discuss today.

Getting the History Right

As I explained in that paper, a comprehensive accounting of China’s WTO accession and the China Shock collapses the hawkish caricature of a naïve U.S. government fueling the destruction of the American workforce in the idealistic hope of Chinese democratization. For starters, China’s WTO accession didn’t actually open the United States to Chinese imports: From 1980 until it was admitted to the WTO, China faced no greater trade barriers than other (“most favored”) U.S. trading partners because Congress approved that designation annually:

Meanwhile, the probability of congressional revocation of China’s trade status had basically evaporated by the late 1990s. (One analysis put the odds of denying normal trade relations at about 5 percent during that decade.) Likely as a result, Chinese imports were steadily increasing before PNTR, and just kicked into a slightly higher gear in the 2000s:

One can thus argue that China’s WTO accession accelerated the bilateral economic integration, but that train had left the station many years earlier and was chugging right along when China finally joined the WTO. (Though it should be noted that not everyone agrees with even the “acceleration thesis”: Per this new World Bank paper, for example, it was previous economic liberalization—not PNTR or WTO accession—that accelerated Chinese trade growth in the 2000s.)

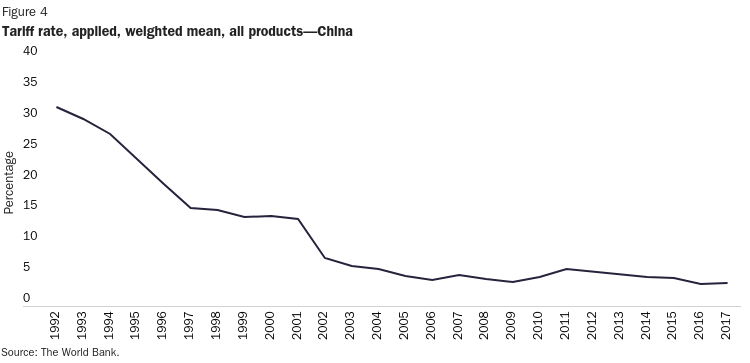

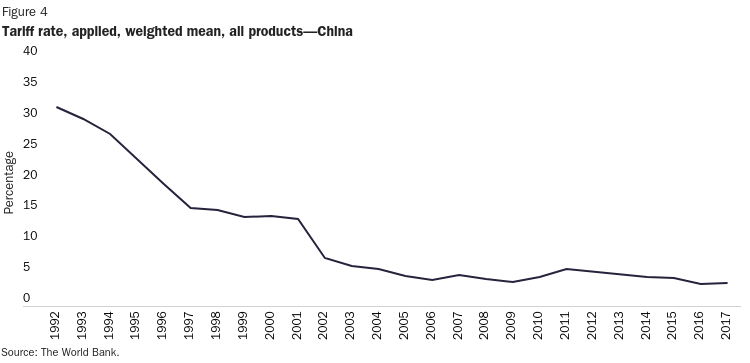

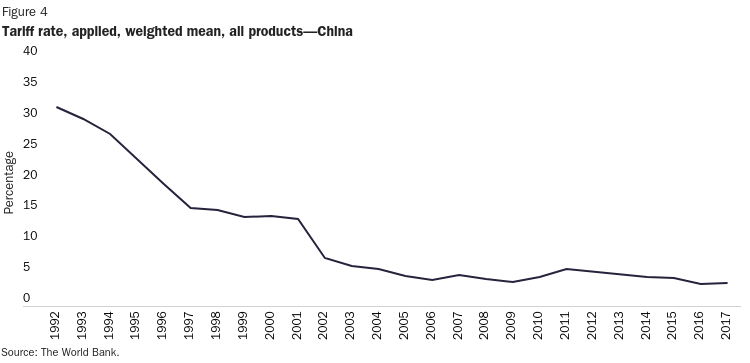

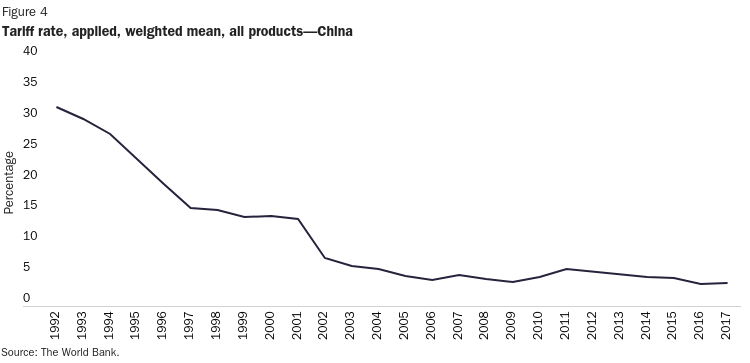

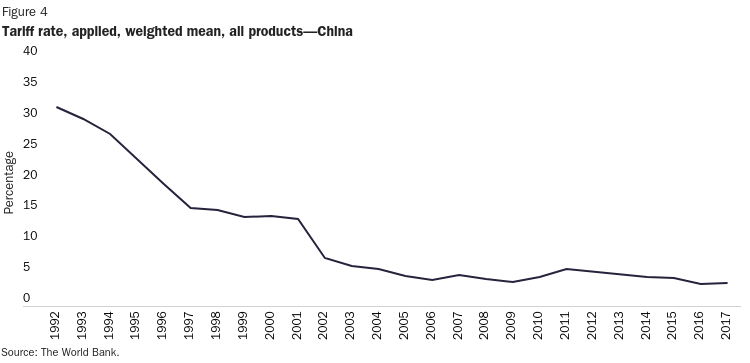

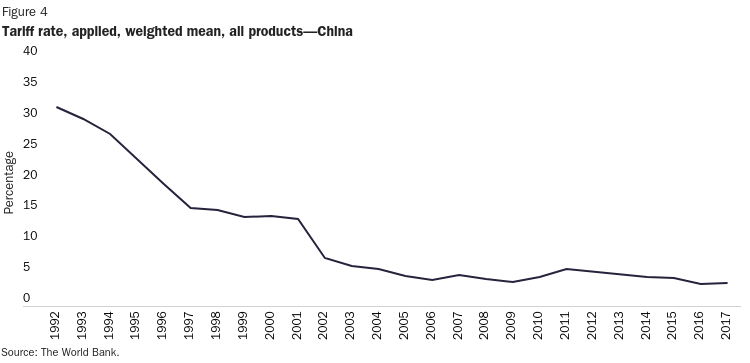

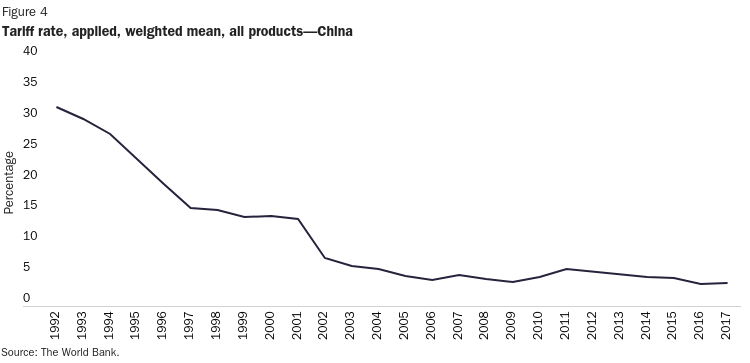

It’s also a myth that the United States just rubber-stamped China’s WTO entry because of neoliberal dreams of a free trade paradise or Chinese democratization. Accession took more than 15 years and required dozens of intergovernmental meetings, negotiating texts, and, importantly, Chinese economic reforms. We discussed some of these reforms earlier this year, but here’s one more: Average tariffs in China dropped from more than 30 percent in the early 1990s to less than 5 percent in 2006 (and less than 3 percent in 2019). And it’s these market-oriented reforms, not U.S. tariff reductions, that primarily drove China’s post-WTO export competitiveness—something even the “China Shock” authors acknowledge (and why other countries, even ones with high import barriers like India, experienced their own “China Shocks”).

Meanwhile, the United States was the last big nation to approve China’s WTO accession via bilateral negotiations, demanding over a contentious 13-year period ever more concessions from the Chinese government, including protectionist ones like the right to impose special “safeguard” and “trade remedy” (anti-dumping and countervailing duty) restrictions on Chinese imports. Today, the U.S. still uses the special anti-dumping methodology, and China is by far the largest target of ever-growing U.S. anti-dumping/countervailing duty measures:

Behold, the neoliberal economic consensus!

Anyway, key Clinton administration speeches and policy documents during China’s WTO accession also show that bilateral economic engagement was primarily a pragmatic decision to achieve commercial (i.e., export and investment) and foreign policy (e.g., North Korea) objectives, not Chinese “democratization” or Smithian consumer gains. Political reform was a secondary issue that advocates believed was, while not guaranteed, more likely with WTO accession than without it.

In reality, mercantilist Washington policymakers were enamored with China’s export potential and, quite frankly, had little choice to pass PNTR and ultimately admit China into the WTO: every other WTO member had agreed to admit China years earlier and would thus enjoy expanded access to the Chinese market while the U.S. dithered; China was a growing, billion-person nuclear power reforming economically (unlike today); the WTO already included Communist Cuba, Eastern Bloc command economies, and “socialist” countries with pervasive state-owned industries; Congress would have continued approving normal trade relations anyway; and, even with higher U.S. tariffs, globalization (and, as we discussed, U.S. customs law’s “rules of origin”) would’ve allowed Chinese goods to enter the United States as parts of “non-Chinese” products—just as they’ve done during the current “trade war.”

In short, China was getting into the WTO, and rejecting PNTR would’ve just punished U.S. companies (especially exporters and farmers), heightened diplomatic tensions, emboldened Chinese hardliners who opposed the WTO, and denied the U.S. government a new venue to press for reforms—all while failing to prevent China’s rise. Thus, the actual alternatives to PNTR—a critical counterfactual that today’s critics conveniently ignore but was a prominent part of the political debate back then—would’ve been economically and geopolitically inferior to the decision that was made.

This wasn’t free trade dogma (or whatever); it was a cold, complicated reality.

Getting the Economics Right

Then there’s the “China Shock.” As already noted, China’s WTO accession probably improved the country’s export competitiveness, but it wasn’t the main driver. Free market internal reforms –expanding property rights, trading rights and privatization; eliminating price controls and import/export restrictions; etc.—were. (As an aside, it’s more than a little ironic and depressing that the growth China achieved via freer markets is so often the main excuse American politicians now use to abandon freer markets here at home.)

Furthermore, the China Shock’s “American Carnage” has been wildly exaggerated. First, some perspective: The 2 million or so American jobs supposedly destroyed over the entire 12-year period would be less than the average weekly unemployment filings during the height of the pandemic. Even in normal times, the U.S. economy sees about 7 million job losses each quarter (about 400,000 in manufacturing), and the 1 million manufacturing jobs said to be lost to the China Shock constituted less than 20 percent of all such losses (and less than 5 percent of all job losses) over the same period. Does that demand radical policy changes?

Second, studies completed since the original China Shock research show fewer American jobs lost; significant consumer benefits in terms of lower prices and increased variety (always remember: people trade, countries don’t); substantial U.S. employment gains in services (including blue collar ones like construction and transportation), export-oriented manufacturing, and agriculture; and net economic benefits for the country as a whole. There are too many such papers to discuss here, but one deserves special mention: Economists Xavier Jaravel and Erick Sager found in 2019 that Chinese import competition during the China Shock significantly lowered the prices of various goods in the United States and thereby generated about $410,000 in “consumer surplus” for each American job lost (as calculated by the China Shock papers). The original China Shock authors just recently acknowledged these benefits in an update to their original work and found that, once you add in the consumer side of the Chinese trade ledger, only 6.3 percent of the U.S. population lived in a place that—per their own calculations—experienced a significant negative “net welfare effect” due to trade with China.

Thus, even if one were to treat the China Shock as economic gospel (several economists, it should be noted, disagree with it) and pin most job losses on WTO accession and PNTR, the economic gains for the country were substantial and the losses were relatively small and concentrated. This is, of course, precisely what the economics literature would expect—not some magical exception that justifies generally abandoning freer trade.

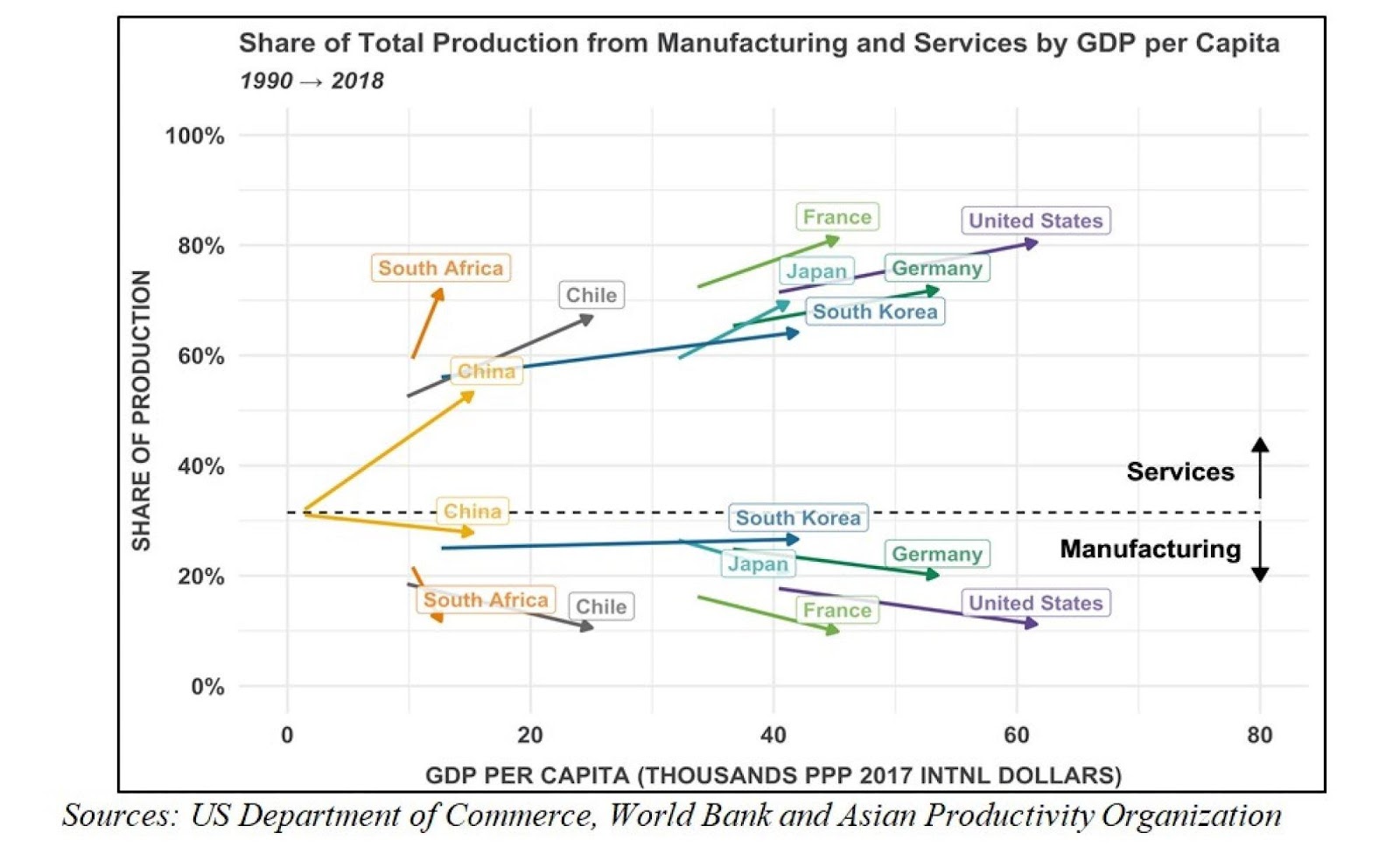

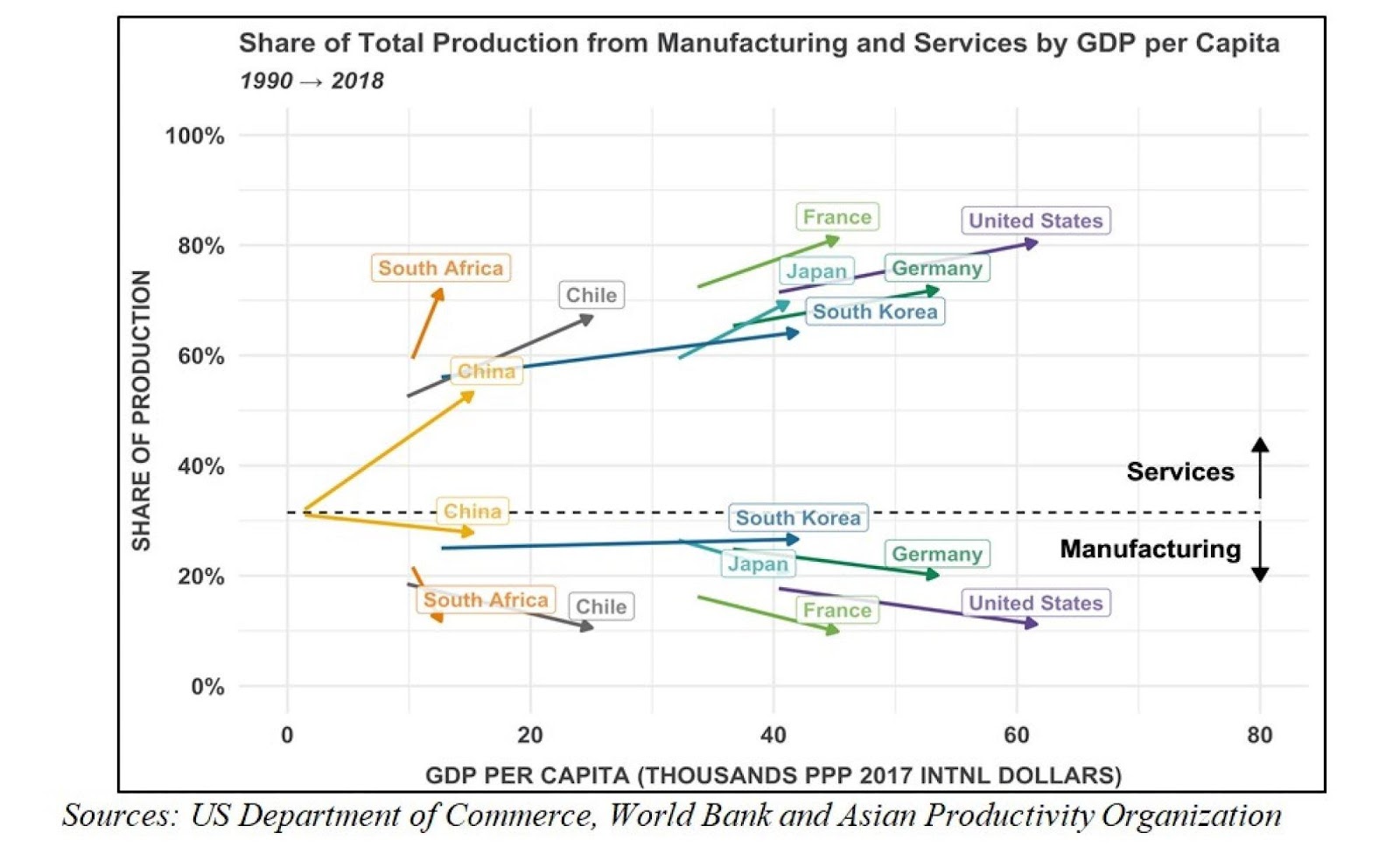

Finally, studies show that U.S. low-skill manufacturing jobs and industries probably would’ve struggled in the 2000s, regardless of the China Shock, because of automation, competition from other states or developing countries, and—of course—the Great Recession. In fact, manufacturing jobs as a share of the U.S. workforce experienced only a modest change in their downward trend before and after China entered the WTO, and Chinese imports replaced other imports (particularly those from Asia), not domestic production, between 1990 and 2017.

These studies and numbers help to answer another counterfactual question that critics rarely ask: What would have happened without the China Shock? They indicate that more import restrictions wouldn’t have saved most of the U.S. manufacturing jobs destroyed between 1999 and 2011—they would have simply changed the destroyer to other things. Indeed, officials in the George W. Bush administration came to this same conclusion when examining the data at the time, and it’s exactly what happened when the Obama administration blocked Chinese tire imports under the special “safeguard” mechanism agreed as part of China’s WTO accession: Instead of China tariffs boosting domestic production, imports simply shifted to non-China sources (while prices, of course, increased and the economy suffered overall). This same “trade diversion” whack-a-mole also resulted from Trump’s new tariffs on Chinese imports and the hundreds of “trade remedy” duties imposed since 2001.

In short, ditching the “neoliberal economic consensus”—leaving aside whether it’s a real thing that ever existed here—and restricting Chinese imports simply wasn’t going to save American workers from the disruption inflicted by the China Shock. And, as we’ve repeatedly discussed, the general trends for the American working class—jobs, wages, etc.—since the China Shock began in the late 1990s have been positive.

And Then What Happened?

Maybe the most stunning part of populists’ continued insistence on relitigating China’s WTO accession is how it ignores not only the vast economic literature on protectionism’s harms and inefficacy (as well as the United States’ decent success versus China at the WTO), but also our own recent history of abandoning multilateral engagement. On the former issue, I’ll just note the numerous reports cited in my paper showing that, while China certainly has shirked some of its WTO obligations (as basically all WTO members, including the United States, do), it has tended to comply when pressed by countries through dispute settlement. The problem, however, is that U.S. policymakers just didn’t press very often, even though legal experts show that—contra the populist rhetoric—much of Chinese economic malfeasance is covered by WTO rules. As I wrote last year—

The refusal of the United States and other WTO members to pursue more disputes against China—or open “compliance proceedings” when China does not fully comply—is a policy choice worth criticizing, but this says nothing about the original decision to admit China to the WTO. Indeed, it is either mistaken or misleading to claim that China’s WTO accession terms were weak and that the WTO has utterly failed to discipline China’s unfair trade practices when the sole means of imposing such discipline—dispute settlement—and the “WTO-plus” rules that China accepted have never been fully utilized. This is declaring defeat before ever firing a shot.

Of course, certain parties in the United States—for example, those wedded to maintaining our trade remedies system (despite multiple WTO rulings against it) or our bloated farm subsidies (which more recent WTO negotiations have targeted)—have a strong incentive to see the WTO collapse, but what’s everyone else’s excuse?

And then there’s our recent experience with the alternative to slow, messy multilateral engagement. As we discussed a few weeks ago, President Trump’s abandonment of the WTO and implementation of a broad range of tariffs, sanctions, and investment restrictions against China harmed American manufacturers and the economy more broadly; emboldened Chinese nationalists and pushed the CCP and once-hesitant Chinese companies to double-down on industrial policy and economic self-sufficiency; alienated U.S. allies, even pushing some closer to China in the process; and fueled cronyism and political mayhem here at home. It also didn’t help American workers: as the China Shock authors put it in their new paper, “The subsequent U.S. China trade war succeeded in elevating U.S. product prices but not in expanding employment in import-protected sectors. We are aware of no research that would justify ex-post protectionist trade measures as a means of helping workers hurt by past import competition.”

Meanwhile, China’s stances on human rights, Hong Kong, Taiwan, the South China Sea, and other issues have deteriorated - in many cases, significantly. In fact, the only thing that appears to be slowing China down at this point is China (insert crocodile tears here).

Summing It All Up

So why do we keep talking about a 20 year-old trade event anyway? Well, I see a few reasons:

First and most obviously, China over the last decade or so has taken a severe turn for the worse, and its size, state capitalist model, and integration into the global economy (which, again, started long before WTO entry) make for a very difficult and complicated challenge for Western policymakers—far more so than the isolated, economically backward Soviet Union during the Cold War. Bashing the imperfect WTO and promising broad-based industrial policy and isolationism make for a policy “answer” to a complex problem that’s clear, simple, and—as usual—wrong. (Just look at Cuba, North Korea, and Iran, where decades of American economic coercion—far more intense than Americans would ever tolerate against China—have failed to dislodge authoritarian regimes that are far smaller and weaker than China.) Real policy solutions, on the other hand, will be a slog, with some losses sure to accompany any broader victory. But, c’mon, who can wait for that?

Second, the current obsession with China’s WTO entry can distract from the myriad U.S. policy failures that actually did boost China or hobble American companies and workers since then. Most notably, successive U.S. administrations pursued too few WTO disputes in response to real Chinese trade infractions, even though global trade rules can discipline key irritants like industrial subsidies and intellectual property; they helped sandbag new WTO negotiations to save politically-popular U.S. protectionism and subsidies, even though those programs harm the economy; they maintained significant restrictions on high-skill immigration, despite oodles of evidence that these workers bolster U.S. industry (especially high-tech services and manufacturing) and undermine China (via “brain drain”); they failed to pursue—or outright opposed—trade agreements like the Trans-Pacific Partnership, a deal intended (in part) to counterbalance China’s economic and geopolitical ambitions; and they sat idly by as bad tax, education, licensing, criminal justice, zoning, welfare, and other policies left American workers unprepared to compete in a global economy or less able to adjust and recover when disruptions occur (as they inevitably do). People don’t like China right now (for good reason!) and blaming foreigners has a long and effective political history, so if you have, say, presidential aspirations and were in office during some of the China Shock period, you can blame all of the world’s ills on China and hope that people won’t notice your own contributions to the Plight of the American Worker. (Same goes for the union bosses, CEOs, and state/local officials who presided over decades of American Sclerosis.) Much better to break out the Great and Powerful Oz, lest Dorothy and the gang look behind the curtain.

Third, China provides budding policy entrepreneurs on the left and right who, for whatever reason, don’t like trade, the WTO, or freer markets with a convenient justification for abandoning the “dead consensus” (or whatever) without much scrutiny of what their alternatives would do. Trade is almost always the result of voluntary, mutually beneficial exchange between individuals (even when the guy on the other side of that trade resides in China), and we have mountains of evidence showing that trade restrictions impoverish both parties, generate net economic losses, empower cronies, and usually imperil (rather than bolster) national security. At the same time, China is an increasingly common excuse for implementing all sorts of U.S. restrictions on goods, services, and labor from other countries (see, e.g., Trump’s global steel tariffs or new currency tariffs against Vietnam) or enacting other government interventions in the economy (e.g., semiconductor subsidies). Characterizing these policies as a necessary front in some epic battle between Great Powers—and tarring all critics as foolish “neoliberal” appeasers personally responsible for China’s rise and the pain of millions of American workers—can relieve proposed interventions of the typical cost-benefit analysis.

However, as the last few years have re-taught us, such an analysis remains necessary—and especially for China, which arguably represents this generation’s most difficult and pressing geopolitical challenge. The recent and historical record of using broad trade and immigration restrictions, subsidies, and bellicose unilateralism to achieve core economic and geopolitical objectives is weak.

No wonder advocates want to ignore it.

Chart(s) of the Week

The Links

NYT deep dive into why we can’t build anything here (my blog post on the same)

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.