Dear Capitolisters,

As readers here surely know (and as we’ve covered here repeatedly), inflation is unquestionably the top economic issue in the country right now, and it has been for quite a while. In fact, we’re approaching the one-year anniversary of the first time I dug into the risk of the U.S. economy “overheating” in the months ahead (a piece that, in retrospect, holds up pretty well!). And it seems that not a day goes by that there isn’t some sort of breaking news about inflation in the U.S., whether it’s on new data, Federal Reserve stuff, legislative or executive branch actions, or the political ramifications. On the last two items, in particular, it’s become increasingly clear that rising prices are issue No. 1 for American voters and, therefore, Washington politicians—including the president—already eyeing the November midterms.

So why, then, does the Biden administration keep doing things to boost, not mute, inflationary pressures?

Inflation Update: Still Frothy Out There

Before we get to that, however, let’s briefly recap where things now stand. After several months of uncomfortably high inflation in 2021 deflated summertime hopes that price gains would be “transitory”, the Federal Reserve earlier this year began raising interest rates and just recently signaled that it will not only increase the magnitude of future rate increases (from a quarter point to half a point) but will also begin reducing its “mammoth” $9 trillion portfolio of Treasury and mortgage securities (acquired to implement “quantitative easing”). They’re meeting today to confirm these plans, the goal of which is to temper domestic demand while avoiding a “hard landing” that pushes the U.S. economy into a recession. The balancing act will not be easy.

Inflation figures like the consumer price index (CPI) and personal consumption expenditures price index (PCE), meanwhile, are still pretty high—especially when including volatile food and energy supplies affected by the Russia-Ukraine conflict—but they do show some signs of moderating when you strip out the noise. Nevertheless, things are still quite frothy out there (see, for example, the latest “employment cost index” for wages and salaries, which just hit a record), and inflation is the top concern of large majorities of voters, who (quite rightly) view it as a “very serious issue” that affects them personally. Unsurprisingly, Americans’ economic concerns mean political pain for the party in power in Washington: Joe Biden’s approval numbers are in the toilet, and Republicans are poised for major gains in the November midterms.

Readers can skim previous newsletters for the basics of what inflation is and how it works, but for today’s purposes it’s enough to recall that inflationary pressures reflect both supply side and demand side factors, the precise weighting and contribution of each being unknowable and subject to significant scholarly debate. As the New York Times noted back in January, a diverse group of economists believe that demand-side policy—deficit spending and monetary policy—should shoulder most of the blame for today’s high inflation, but the White House (for political or substantive reasons) has pointed more to the supply side, in particular global supply chain snarls and other pandemic-related issues that have caused shortages and prevented capacity expansions here and abroad. “The inflation has everything to do with the supply chain,” Biden said in January. Thus, per the NYT, “The White House has tried to address inflation by boosting supply — announcing measures to unclog ports and trying to ramp up domestic manufacturing, all of which take time.”

I tend to think that “blame (mostly) demand” folks like former CEA chair Jason Furman, monetary expert Scott Sumner, and Stanford’s John Cochrane have the better of the argument these days (national output is now above trend), but such a verdict is immaterial for today’s purposes. Why? Because the White House is supporting policies that affect both supply and demand in the United States in ways that would most likely increase inflationary pressures.

Supply Side Restrictions Are Actually Increasing

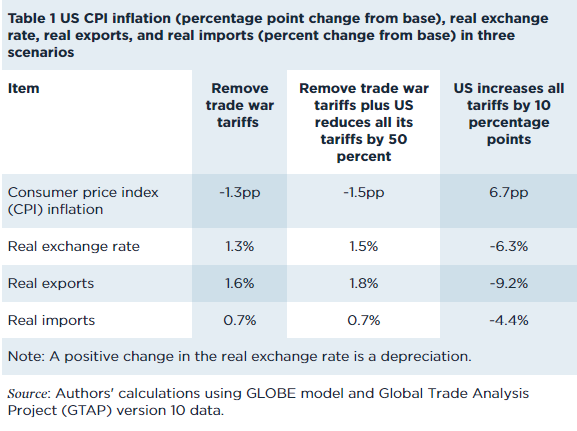

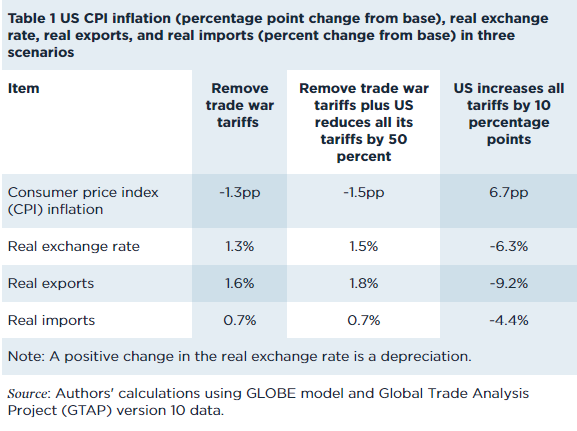

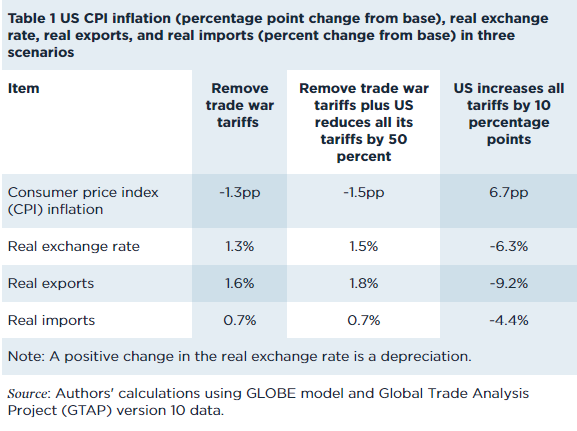

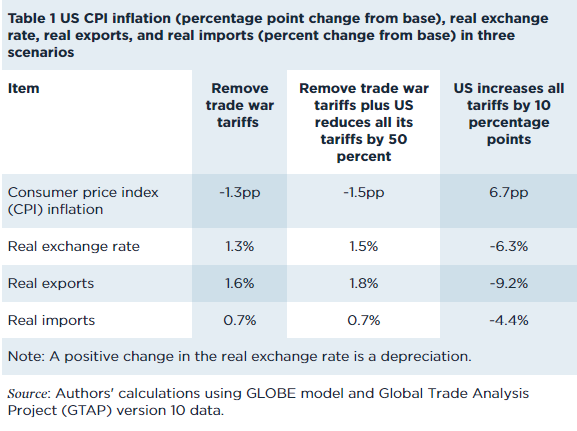

The most obvious place to begin on the supply side is with trade. As we discussed a few weeks ago, for example, one of the big selling points for trade and global value chains are their benefits to consumers via lower prices, thus potentially helping to temper inflation. And, as Dartmouth economist Doug Irwin noted yesterday in a useful Twitter thread, previous studies have repeatedly shown that Trump-era tariffs increased domestic prices. (More on that here and here.) Now comes new research from the Peterson Institute of International Economics (PIIE) finding that eliminating various U.S. tariffs would put downward pressure on domestic prices, while increasing tariffs would (unsurprisingly) do the opposite:

A separate PIIE report adds that “a 2 percentage point reduction in tariff-equivalent barriers would deliver a one-time decrease in CPI inflation of 1.3 percentage points, saving the average American household $797 per year.” These authors examine not only tariffs, but also other U.S. trade restrictions, such as “trade remedies” (anti-dumping, anti-subsidy, safeguard) on lumber and fertilizer, “Buy America” rules governing federal procurement, and Jones Act restrictions on domestic shipping. (Frequent readers of Capitolism, of course, know these measures well!) In both studies, the authors note that trade liberalization’s price-tempering effects occur not only through lower import prices but via enhanced competition with American-made goods, which puts downward pressure on those prices too. Oodles of evidence (scholarly and anecdotal) backs them up.

Of course, liberalizing trade isn’t some inflation silver bullet, but most fixes are out of the president’s hands, and every little bit helps—especially for a White House supposedly putting “all tools on the table to beat inflation”. Thus, as Furman told Axios recently, “Removing the China tariffs is the single-largest policy lever to bring down inflation that President Biden has.” This solution should come as no surprise to the president. His own treasury secretary (and former Fed chair), Janet Yellen has, for example, repeatedly acknowledged that lifting U.S. tariffs might help cool prices a bit. Deputy National Security Adviser Daleep Singh recently said the same thing. Indeed, in targeting our ports for anti-inflation action, the “blame the supply side” president has himself (tacitly) admitted that easing U.S. trade restrictions could ease inflation. New import competition might also push American corporations to lower their markups and accept lower profits—another target of Democrats’ economic ire. So you’d think, then, that a Biden administration laser-focused on inflation (and with limited options for congressional action) would be eager to use the ample discretion afforded to it under U.S. trade law to roll back any and all restrictions on imports.

Most importantly (and depressingly), the Biden administration has done little on Trump’s tariffs on steel, aluminum, and Chinese-origin imports, even though these measures could be lifted today via executive order. The administration did negotiate metals deals with Europe, Japan, and the U.K., but the agreements provided only modest relief (replacing the tariffs with onerous “tariff rate quotas,” which allow a set quantity of goods to enter duty-free and then tax everything else), and steel prices in the United States remain well above world prices or even prices in Europe (where a war and subsequent commodities crisis is occurring!). The costlier China tariffs, meanwhile, remain untouched—despite, as my Cato colleague Clark Packard just noted, utterly failing to achieve their geopolitical objectives by the Biden administration’s own standards.

Meanwhile, trade remedy duties on steel (e.g., oil and gas drilling pipes), construction materials (including lumber and nails), fertilizer, intermodal chassis, solar panels, and hundreds of other products are also restricting supplies and raising U.S. prices—adding to other inflationary pressures in red-hot industries like energy, homebuilding, and transportation. As we’ve discussed, the laws allowing for these duties are the biggest problem here, so major reform requires congressional action. However, the White House isn’t entirely blameless, either. For one thing, trade remedy laws provide ample discretion to the Department of Commerce to calculate lower (or higher) duties, but there’s no sign the executive branch agency is trying to limit the damage. (Indeed, it doubled lumber duties last year as part of an annual review.) The president also hasn’t put forth any proposals to reform these laws and expressly praised the recently passed House “China bill” that would expand, not limit, the potential harms caused by U.S. trade remedies laws.

Indeed, the only real tariff relief we’ve seen since Biden took over was a small deal with Europe pausing duties related to the longstanding bilateral feud over aircraft subsidies. Meh.

It’s even worse on Buy America and the Jones Act. The president is, of course, a big fan of the latter, and his administration hasn’t done anything—granting waivers, pushing reforms—to cast that fandom into doubt, even after the Russian invasion again showed the law’s shortcomings. On Buy America, my Cato colleague Colin Grabow just documented how Biden just recently announced even-more-onerous localization mandates for federal procurement contracts, further inflating project costs. Studies have found, in fact, that Buy America rules act as a barrier to entering the U.S. market and raise domestic prices in the same way that a tariff does, and these mandates confounded infrastructure projects authorized by the 2009 stimulus law (which then‐Vice President Biden administered). It’s thus no surprise that the latest Buy America restrictions announced by the White House were panned by the Associated General Contractors of America because they’d inflate costs.

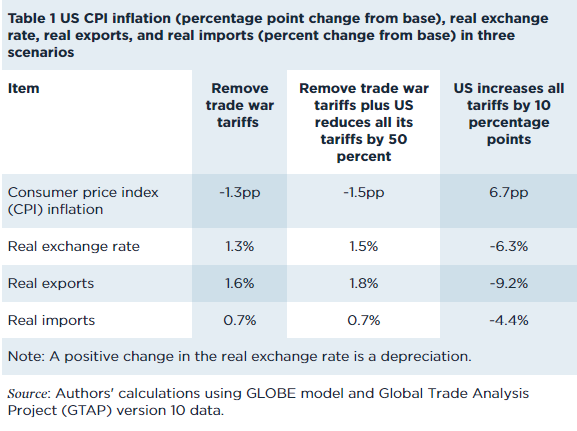

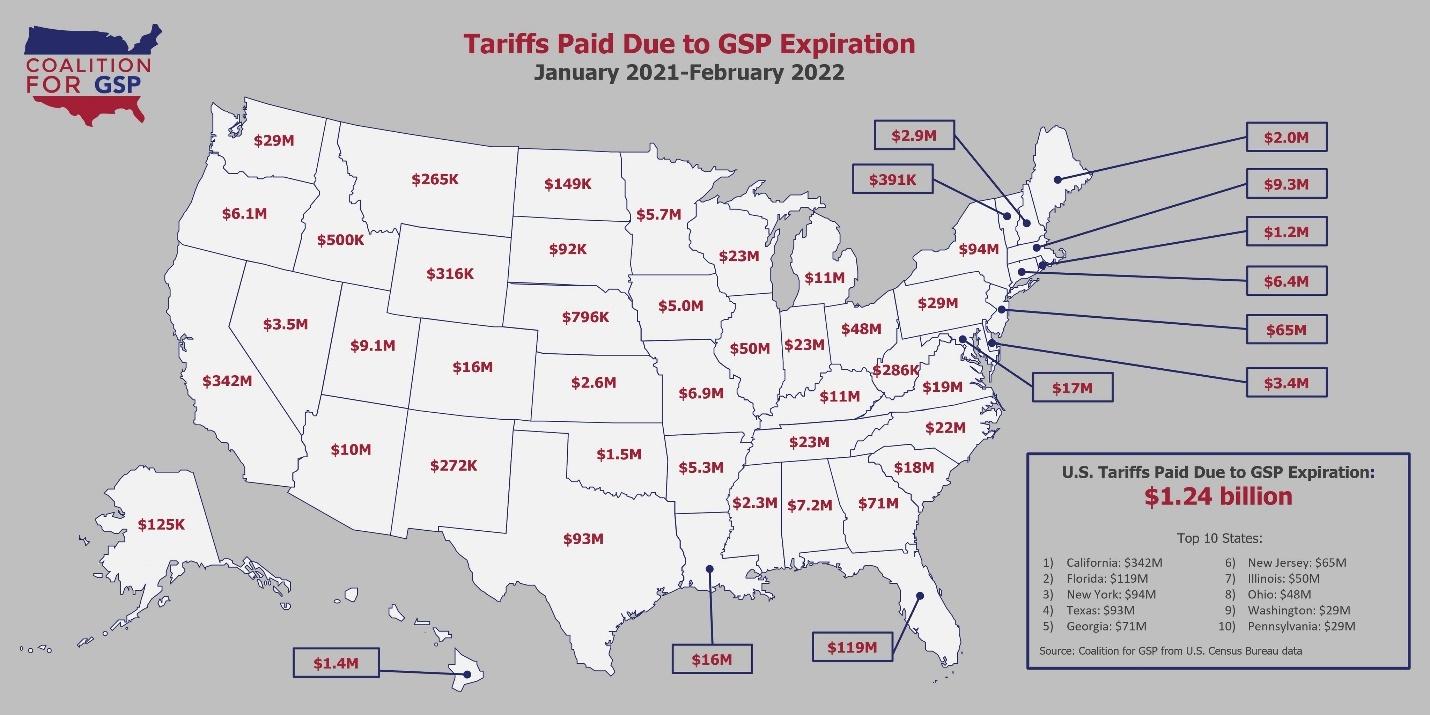

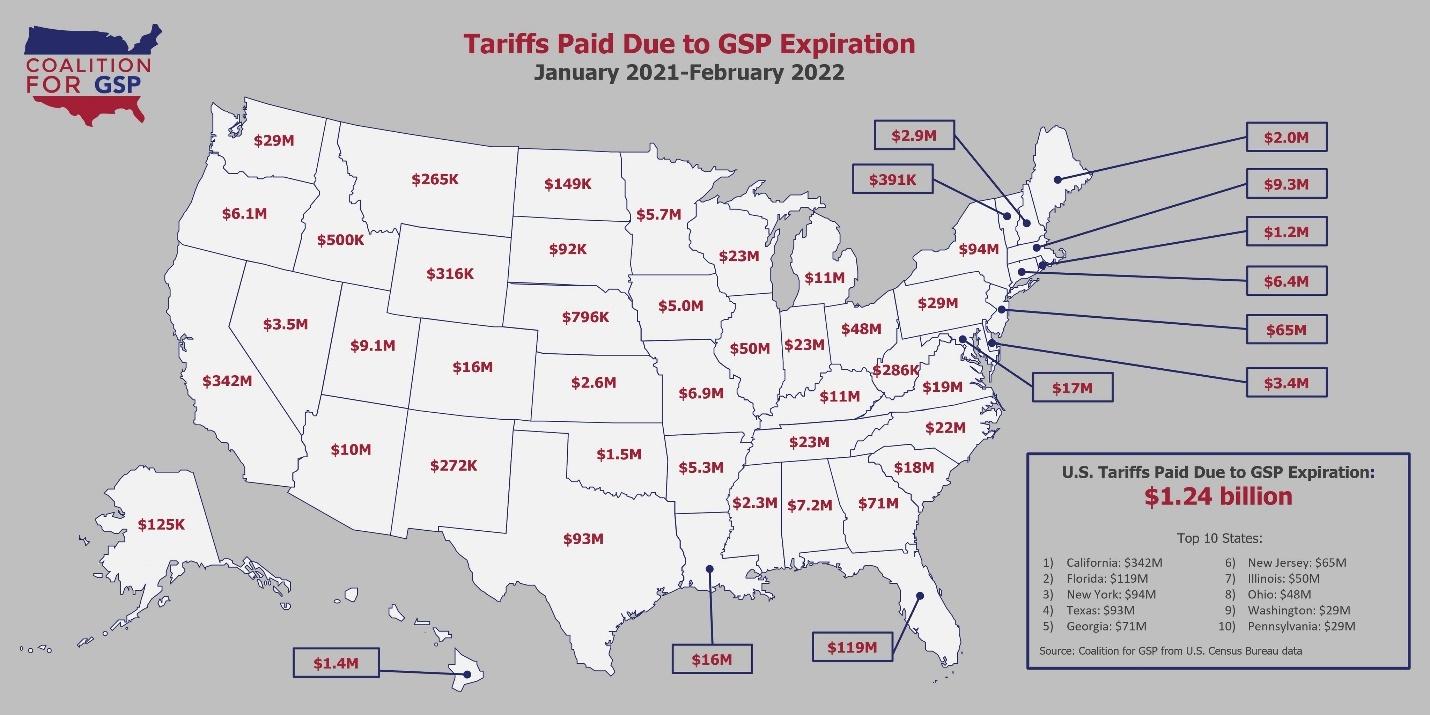

The Biden administration has also ignored other trade issues exacerbating our supply chain problems and raising domestic prices, such as continued U.S. restrictions on Mexican trucks (see this great Dominic Pino piece for more); high “normal” tariffs on things like pickup trucks, clothes, footwear, and food; and the still-expired Generalized System of Preferences, which has long allowed U.S. companies to import products from certain poor countries (not China) duty-free in order to save those companies some money and help the countries develop:

In short, trade policy remains the unplayed card in the current inflation fighting game, and the Biden administration seems intent on keeping it that way.

But It’s Not Just Trade (or the Supply Side)

The Biden administration’s supply-side restrictions, however, don’t stop at trade. For example—

It issued a “highly controversial” executive order in February requiring union-friendly “project labor agreements” for every contractor or subcontractor engaged in a federal construction project worth more than $35 million. Numerous studies have shown that government-mandated PLAs significantly reduce competition and raise construction costs.

In March, Biden's Labor Department proposed updates to "Davis-Bacon Act" regulations that would further increase already-high wage rates for federal construction projects by eliminating Reagan-era reforms that were specifically intended to temper 1970s-era inflation. As the American Action Forum noted at the time, “the proposed rule, if finalized, would increase the labor costs associated with federal construction projects.” This could not only reduce the return on government (taxpayer) infrastructure investments but also goose inflation from the supply side (higher construction labor costs and fewer qualified contractors) and demand side (union construction workers with more money to spend). The labor law specialists at Littler agree: “There is reason for concern that DOL’s proposed return to discredited policies of the 1970s will result in inflated wage rates that are inconsistent with the DBA and will exacerbate the current inflation in the U.S. economy.”

In April, they moved to reverse Trump-era reforms to the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), which has—as we’ve discussed—been repeatedly found to raise infrastructure costs and delay federal projects. The Biden administration move, which will expand the scope of environmental reviews and regulators’ discretion, elicited quick condemnation from business and farm groups, as well as many “supply side liberals” (and, of course, conservative supply siders too) for raising costs and endangering important projects, including many environmental ones.

Other Biden proposals under consideration, such as new “reciprocal switching” mandates for freight rail, raise similar supply side concerns.

Moving to the demand side, the White House has ditched its big-spending “Build Back Better” plan, but, as Heritage’s David Ditch detailed a couple weeks ago, there is plenty of deficit spending—which per the San Francisco Fed helped goose inflation last year—on tap. (The budget proposal Biden released in March was similarly spend-happy.) Surely, not all or even most of these spending plans will be implemented, but some—such as additional COVID-19 funding and the House/Senate “China” (read: semiconductor subsidy) bill, which CBO estimates will throw another $65 billion log onto the fire—surely will. Indeed, as a new AAF analysis shows, the supposedly-must-pass “semiconductor subsidy bill” has now morphed into a $400 billion, unfunded behemoth:

(Hooray, industrial policy!)

Recent Biden administration moves regarding student loan debt forgiveness—in particular, a recent extension moratorium on payments through August and proposals to forgive thousands of dollars of debt for all but the highest earners—might also stoke demand. The Washington Post reports, for example, that the most recent plan to forgive $10,000 in debt for singles earning below $150,000 and couples under $300,000 would cover 97 percent of all student debt and cost roughly $245 billion. It’d be highly regressive, legally dubious, and fail to reform the broken U.S. student loan system—and it might also boost inflation.

That last point depends on all sorts of things, but it’s certainly reasonable to think that millions of individuals suddenly freed from paying off some portion of their loans each month would redirect at least some of their windfall savings into the market. Thus, the Post notes, former Treasury Secretary Larry Summers raised “concerns” that student debt cancellation “could increase inflation, depending on the total amount of loans forgiven.” The Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget agrees, estimating in February that “cancelling all $1.6 trillion of student debt would increase the [PCE] inflation rate by between 10 and 50 basis points (0.1 to 0.5 percentage points) in the 12 months after repayment is scheduled to begin.”

Indeed, as Bloomberg noted last week, goosing demand was the whole point of the original moratorium: "[w]hen debt payments were frozen in 2020, it was part of a wider effort to prop up demand in the pandemic slump. That rationale doesn’t apply now, with the Federal Reserve battling soaring inflation and trying to rein in spending, not boost it."

Yet here we are.

Summing It All Up

For a White House supposedly convinced that our current inflationary problems are mainly a supply side issue, they sure have a weird way of showing it: the administration is not only maintaining various policies that restrict available domestic supplies of goods and services but in some cases actively working to increase those restrictions, while also goosing domestic demand a bit too. In this regard, Scott Sumner recently agreed with Larry Summers that the Biden administration could “do a few things at the margin” to slow inflation—reducing tariffs, scaling back Buy America restrictions—“but their actual policy has been almost the exact opposite, to reduce aggregate supply and make the problem worse.” Sumner and Summers are certainly not alone in thinking this way. (Indeed, the list of folks noticing the potential inflationary benefits of trade liberalization reads like a “who’s who” of prominent economists—on the left and right.)

This doesn’t mean, of course, that President Biden really is trying to boost inflation right now—he’s almost certainly not. (Thus finally answering the question in today’s headline, in case you weren’t aware of Betteridge’s Law.) Instead, the president has simply followed the script I laid out last year:

The port situation is indicative of a broader sclerosis that infects significant parts of the U.S. economy—one caused in no small part by the types of policies discussed above. Although those policies cover a wide range of issues, the thread that runs through them is the prioritization of narrow interest group objectives (profits, jobs, home prices, bureaucratic systems, etc.) over broader productivity, capacity, and flexibility improvements…. In almost every case, the insular interests of a politically powerful minority were able to dictate policy to the detriment of the state or nation as a whole—a cost that’s minor and diffuse in the good times, but can become major and acute in the bad ones…

In this case, inflation may be the nation’s top economic challenge and may be top of mind for most American voters, but it plays second fiddle to the narrow interests of certain groups—unions, environmentalists, college grads, etc.—that the White House sees as essential for political success this fall and beyond. So those squeaky wheels will continue to get the oil, regardless of the insular decisions’ broader economic effects. And as long as our laws grant the president (any president) that kind of power, we should expect such unintended consequences—and “American Sclerosis”—to continue.

Chart(s) of the Week

Our labor market remains piping hot:

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.