Editor’s note: We hope you’ve been enjoying Capitolism for the past few weeks. This is the final “free” version of the newsletter. From here on out, you must be a paid member of The Dispatch to receive Scott’s analysis on trade, international economics and (we’re hoping) nachos. The good news is we’re still doing our 30-day free trial on annual memberships, so now is a great time to sign up.

Dear Capitolizers,

Last week, President Trump was back in Ohio campaigning and telling incredible stories about tariffs (as one does). This time, he bragged to the audience that his 2018 washing machine tariffs pushed Samsung and LG to build appliance factories in the United States—factories they’d actually announced in early 2017 (details, shmetails). Trumpian exaggerations aside, the president’s love of tariffs and recent events—including the washing machine brags, his on-again-off-again (again) tariffs on Canadian aluminum, and, of course, the omnipresent China situation—provide us with a good reason to look how the president’s tariffs have performed over the last two-plus years, as well as the many reasons he should never have imposed them in the first place.

So let’s get right to it.

The Theory

I won’t do any better than AEI’s Mark Perry in explaining the basic economics of tariffs, so I invite you to go there and read for yourself. In short, a “widget tariff” raises the price of widgets in the United States, causing (1) consumers to pay more for them; (2) U.S. widget-makers to make more money selling widgets; and (3) the government to take in some tariff revenue. The tariff thus redistributes money that the consumers used to save when buying cheaper, non-tariffed imports to producers and the government. However, this is not an even trade. Some of that “consumer surplus” goes to nobody; it’s simply destroyed—what economists call “deadweight loss” (which would also make a great band name). The tariff thus makes the United States as a whole—consumers, producers and government—worse off in the amount of wealth destroyed (money that consumers, pre-tariff, could’ve spent on other stuff or saved). This is all shown in the following extremely wonky chart (which you can ignore unless you’re studying for an Econ 101 exam or something): pre-tariff, the consumer surplus included a+b+c+d; post-tariff, it’s just the green part.

The History

The theory is, of course, backed up by centuries of history and economic analysis. For example, in a 2017 paper, I looked at dozens of government and academic studies examining various eras in U.S. history and found that American protectionism (including and especially tariffs) imposed high economic costs on consumers and the economy more broadly—essentially the theoretical deadweight loss above. However, the studies also showed that tariffs (and other protectionist measures like quotas) typically failed to achieve stated government objectives, such as revitalizing protected industries, saving jobs, or opening foreign markets. At the end of the day, the jobs and industries still withered away (or returned for more government help), and the markets remained closed. At the same time, the protectionism did generate lots of political dysfunction—corruption, incompetence, and the like. Dartmouth’s Doug Irwin came to similar conclusions in his subsequent book on the subject (which, by the way, is a must-own resource for trade geeks and people generally interested in U.S. economic history).

The Economic Consensus

For these reasons, there are few issues on which more economists agree than eliminating tariffs. For example, in a 2006 survey of 210 Ph.D. economists randomly selected from the American Economic Association, Robert Whaples found that “overwhelming” majorities agreed that “tariffs and import quotas usually reduce general economic welfare,” and that the U.S. government should therefore eliminate remaining tariffs and other trade barriers (87.5 percent), refrain from restricting U.S. employers from outsourcing work to foreign countries (90.1 percent), and nix U.S. anti-dumping laws (61.3 percent). Other, more recent economist surveys—such as the University of Chicago’s IGM forum—show similar results.

Trump’s Tariffs

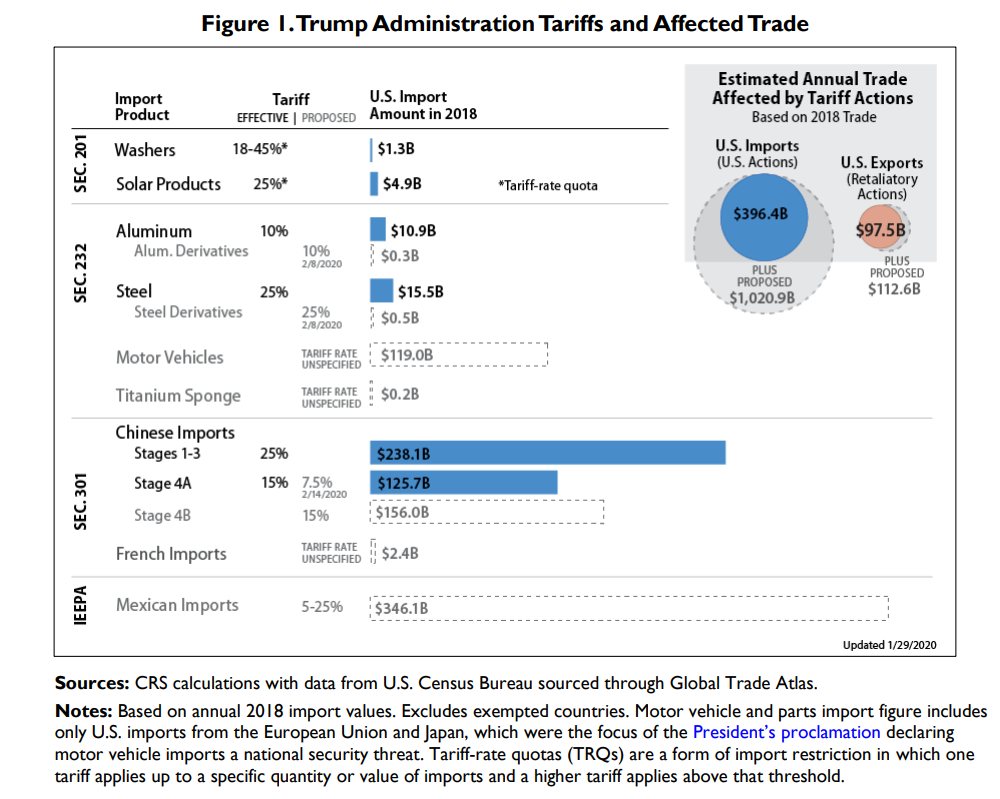

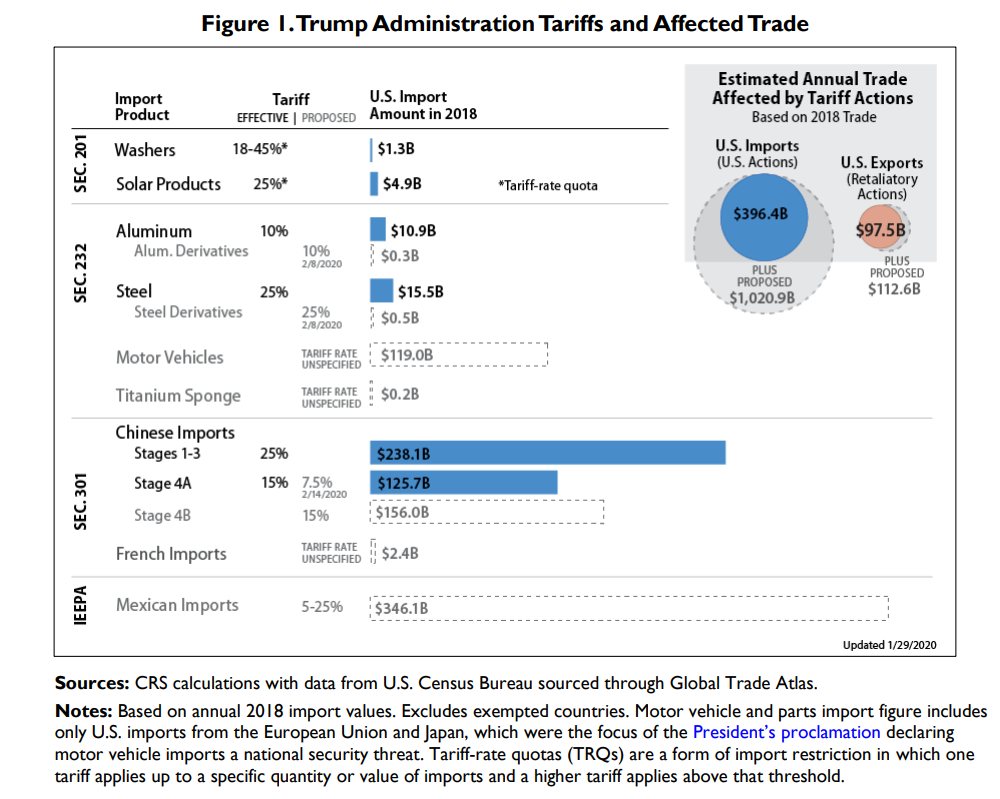

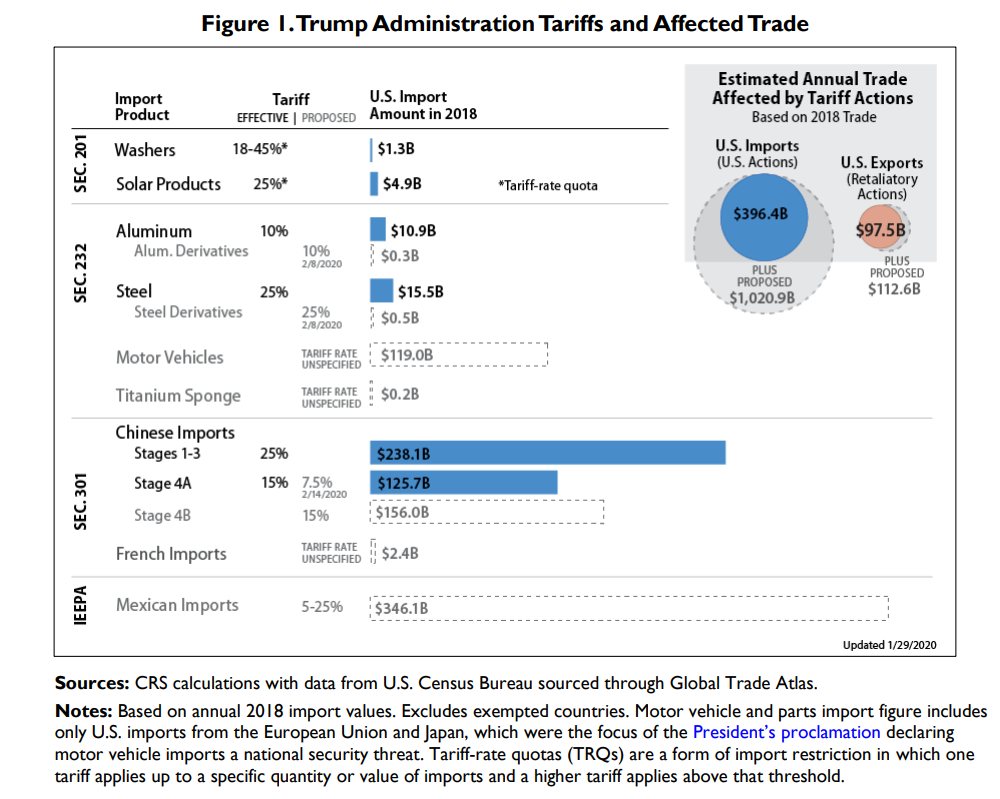

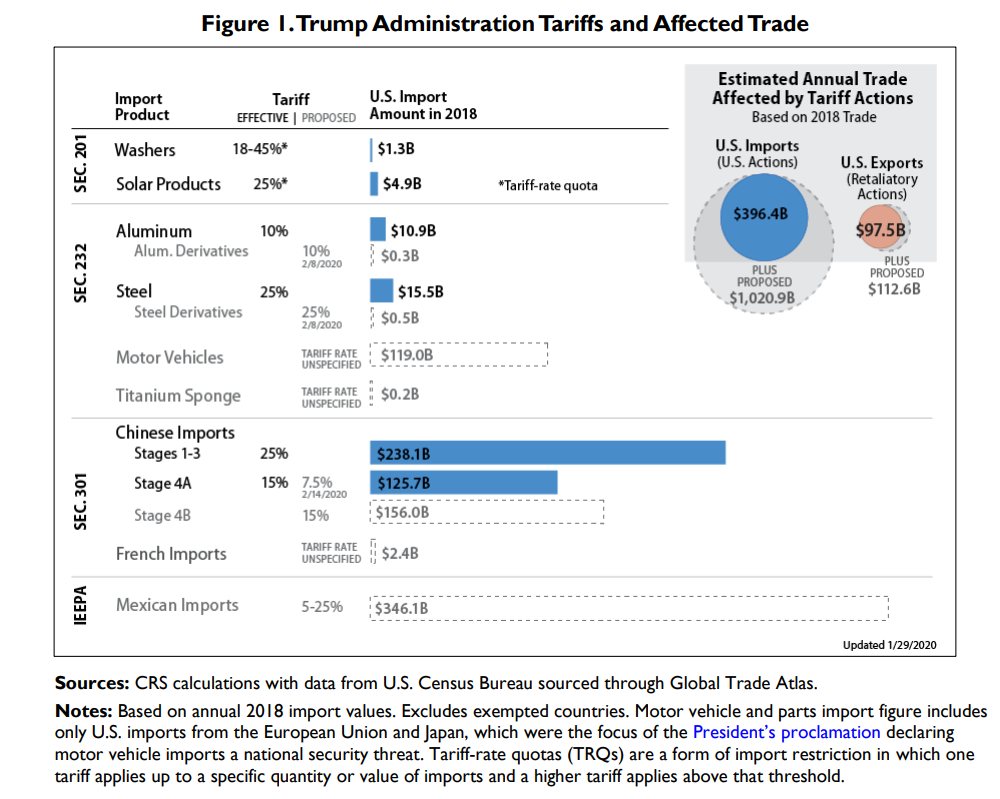

None of this eggheadery, of course, discouraged President Trump from using tariffs for rote protectionist (steel, aluminum, solar panels and washing machines) or geopolitical (China) reasons. This Congressional Research Service report and the accompanying chart below provide the basics—the gray stuff has been threatened, but not actually imposed. (For a more detailed timeline on the measures and their legal bases, go here.)

As you can see, the president, in a break from his predecessors—who were no trade angels but tended to avoid blanket tariffs, especially on national security grounds—has implemented five different tariff actions on almost $400 billion in annual U.S. imports (as of 2018) under three different laws with different rationales: “safeguards,” “national security,” and “unfair trade.” The first two are intended to protect the American industry at issue, while the third is supposed to address foreign government actions that allegedly harm U.S. commerce.

Although Trump’s tariff actions were novel, their results have been pretty much exactly what the theory and history (and a certain T-shirt) predicted:

Let’s walk through each, shall we?

The Economic Costs

The aforementioned CRS report has a pretty good summary of the tariffs’ overall economic costs—borne by both U.S. importers and exporters—as of late January 2020 (almost all of the tariffs remain in place today):

As of January 23, 2020, the United States collected $54 billion from the additional taxes paid by U.S. importers, according to U.S. Customs and Border Protection. These taxes have had a negative aggregate effect on the U.S. manufacturing sector with increased input costs offsetting the gains from increased protection, according to preliminary analysis from researchers at the U.S. Federal Reserve Board. Increasing tariffs also creates greater economic uncertainty, potentially dampening business investment and creating a further drag on growth. Preliminary research, for example, suggests the increase in trade policy uncertainty may have reduced aggregate U.S. investment by 1% or more in 2018. Estimates of the tariffs’ overall economic effects vary, depending on modeling assumptions and the specific set of tariffs considered. Most studies, however, predict declines in GDP growth: the Congressional Budget Office estimated that the tariffs currently in effect would lower U.S. GDP by 0.5% in 2020, below a baseline without the tariffs, while raising consumer prices by 0.5%, thereby reducing average real household income by $1,277. From a global perspective, the IMF estimated that the tariffs would reduce global GDP in 2020 by 0.8%.

(For these and other studies coming to similar conclusions about the tariffs’ economic costs, see this helpful summary from late 2019. Sorry to report that China and other foreign countries have not been paying the tariffs—the studies instead show that U.S. importers (consumers and businesses) have been bearing most of the tariffs’ costs, with foreign exporters bearing little and foreign governments bearing none.)

The CRS further notes that this economic pain was amplified when foreign governments retaliated against U.S. farmers and manufacturers (something everyone, except the president’s closest trade adviser, saw coming): “U.S. exports of targeted industries have declined, with U.S. agricultural exports subject to retaliation down 27% in 2018, compared to 2017. Some U.S. manufacturers are shifting production to other countries to avoid the tariffs on U.S. exports.” Our exporters were also hurt by higher costs for imported manufacturing inputs (i.e., the stuff they need to be globally competitive).

And just as the trade war was hitting high gear at the end of 2018, domestic investment—which was supposed to be stoked by tax reform—started sagging (coincidentally, I’m sure!):

Examinations of specific tariffs—such as those on steel, washing machines, and Chinese imports—came to similar conclusions about their costs, as do various anecdotal reports on the aluminum and solar panels tariffs.

So, all in all, we can safely say that, while the tariffs didn’t implode the economy (which was always a ridiculous assertion), they did hurt American consumers and producers (especially—and ironically—manufacturers and farmers). A lot.

The Failed Objectives

Perhaps those economic costs would be worth it if they achieved the president’s stated objectives. However, the record there, even pre-COVID, is seriously underwhelming:

The steel and aluminum tariffs had a minimal impact on U.S. jobs in those industries, and have done essentially nothing to address global overcapacity (which, per the Trump administration itself, had hurt U.S. producers and was supposed to be fixed by the tariffs). Steel industry stocks actually tanked in late 2018 and early 2019, and steel companies were laying off workers and curtailing investments by the end of 2019. As I wrote in these pages a few weeks ago, the story was similar for U.S. aluminum producers, and it pushed the Trump administration to threaten reimposing tariffs on Canadian aluminum (while also destroying the notion that the tariffs were just leverage in the NAFTA negotiations). In fact, the Trump administration itself has quietly admitted—when extending the tariffs to downstream “derivative” products in early 2020—that they hadn’t increased and stabilized the industries’ capacity utilization. As one Los Angeles Times story put it, “Trump's steel tariffs were supposed to save the industry. They made things worse.”

The washing machine tariffs have been similarly ineffective. As already noted above, major U.S. investments by Samsung and LG were planned long before the tariffs took effect (though the companies do appear to have expanded further since then). A 2019 U.S. International Trade Commission (ITC) examination of the entire industry found that, while domestic capacity and employment increased, actual production declined, “resulting in declining capacity utilization, lower productivity levels, and higher unit labor costs.” Whirlpool (which lobbied for the tariffs) even told the commission that the safeguard “has fallen short of delivering the intended remedial benefits to the continuously operating U.S. producers” due to “unanticipated” responses to the tariffs by foreign exporters (absorbing some of the tariff cost), U.S. importers (stockpiling), and consumers (buying fewer appliances). (All of these actions are common and expected market responses to tariffs.) What Whirlpool didn’t mention, of course, is that its financial difficulties were exacerbated by other Trump tariffs—in particular on steel, aluminum, and Chinese imports. Oops.

The story is essentially the same for solar panels (upstream “cells” and downstream “modules”). There have been few new solar manufacturing jobs, and the ITC’s assessment of thos314e tariffs in early 2020 found that there was “no confirmed new investments in U.S. cell manufacturing”. In fact, the lone remaining producer, Panasonic, was closing down this year, while Suniva, the original petitioner for the tariffs, “had filed for bankruptcy protection and ceased production of cells and modules in April 2017.” U.S. module production has increased, but mainly using imported cells. Imports overall, moreover, had increased substantially.

Finally, there’s China, where the tariffs were less about protectionism (allegedly) and more about geopolitics. However, the result of those tariffs—the “Phase One” deal that Trump signed in January (there will be no Phase Two)—is a mess. As I wrote here in June, for example, the agreement depends on China’s compliance, but provides China with no reason to comply and the U.S. with no realistic way to force their hand. The deal’s terms also make U.S. exporters—especially our Great Patriot Farmers—more dependent on the Chinese market (and, therefore, the Chinese government) and actually encourage U.S. companies to invest more in China. (So much for that economic decoupling.) On the bright side(?) China’s nowhere close to meeting those commitments anyway:

Research also shows that the deal annoyed our allies and encouraged more Chinese economic interventions via subsidies and state-owned enterprises. This is precisely what we want them to stop doing—while the tariffs (which remain in place) have emboldened hardliners in China’s government, stoked anti-American sentiment among the Chinese people, and given Beijing a handy excuse for the (inevitable) results of CCP economic mismanagement.

U.S. Trade Representative Robert Lighthizer recently defended the whole mess as changing the “paradigm” with China, but it’s hard to see how. Whether it’s trade, or the Uighurs, or Hong Kong, or whatever, things in China (and the bilateral relationship) are only getting worse. As Forbes columnist Phil Levy put it, “[t]he Trump administration appears to have made less progress than previous administrations in changing Chinese behavior, and at substantially greater cost.” Indeed.

The Political Dysfunction (Along the Way)

There’s honestly too much dysfunction to list here (and I’ve droned on long enough), but feel free to click through these for yourself to see the cronyism, incompetence, and lawsuits Trump’s tariffs created. American companies that used to ignore Washington now—with their lobbyists’ help, of course—beg it for relief, while the bureaucracy indiscriminately grows ever bigger (and Congress is further sidelined). One issue, however, warrants special mention:

Government payments to farmers have surged to historic levels under President Donald Trump as the Agriculture Department floods the industry with cash to stem the financial losses from Trump’s tariff fights and the coronavirus pandemic.

But as agriculture grows more reliant on unprecedented taxpayer support, farm policy experts and watchdog groups warn the subsidies are growing too big and too fast, with no strings attached and little oversight from Congress—and that Washington could have a difficult time shutting off the spigot.

Direct farm aid has climbed each year of Trump’s presidency, from $11.5 billion in 2017 to more than $32 billion this year—an all-time high, with potentially far more funding still to come in 2020, amounting to about two-thirds of the cost of the entire Department of Housing and Urban Development and more than the Agriculture Department’s $24 billion discretionary budget…. But lawmakers have taken a largely hands-off approach, letting the department decide who gets the money and how much.

More lobbying, more private business groveling, more regulation, and more farm subsidies.

Summing it All Up

Before Trump took office, most experts knew that tariffs were costly, ineffective and politically messy, and we’ve spent the last couple years re-learning that lesson the hard way. Most American manufacturers, as well as the economy more broadly, are worse off; almost every country—allies and adversaries—has retaliated; K Street and the Administrative State are doing what they do best; our farmers may be on a new and permanent dole; and Beijing seems emboldened, not chastened.

But, hey, at least we changed the paradigm.

* * *

Chart of the Week

Really fascinating stuff on generational income/wages from labor economist Ernie Tedeschi:

The Links

“Before long, stabilizing the debt will require an unprecedented fiscal consolidation.” and “The recession has accelerated the day of reckoning"

Photograph by Kyle Mazza/Anadolu Agency/Getty Images.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.