Dear Capitolisters,

One of the most common strategies for political aspirants is to blame incumbents for the disruptions of and imperfections in a market-oriented status quo while promising an amazing-yet-undefined alternative that will never be realized. This has long been the approach of trade-skeptical politicians on the right and the left, and it was practically turned into an art form by Donald Trump who, over the last several decades, blamed anything and everything bad on Japan, NAFTA, China, the World Trade Organization, “trade deals,” and “globalization,” while promising voters that Trump’s unstated alternative would, with super-smart Trump and not those idiot incumbents in charge, easily make the bad things disappear and only good things replace them. The strategy, while cynical, was arguably effective with many Republican voters, given the complexities of international trade policy and that the general, bipartisan consensus for trade and multilateral engagement since the late 1980s often forced American supporters of open markets and the multilateral trading system to rebut such claims with boring discussions of deadweight loss and ancient policies like the Smoot-Hawley tariffs. In short, it’s easy to promise a simple “America First” alternative to the messy trade status quo when voters haven’t experienced an alternative in a long, long time.

Today, it appears that many Republicans want to continue Trump’s approach when accusing Biden and congressional Democrats of being “weak on China” and re-embracing the supposedly obvious failures of past U.S. engagement. (Never mind that neither Biden nor congressional Dems really seem eager to re-engage.) Early 2024 GOP hopeful Tom Cotton, for example, took to the pages of National Review a few weeks ago to blame all sorts of American ills on decades of “economic appeasement with China” (and one of its “oldest architects,” President Biden) and to offer a contrasting, hawkish policy of “targeted decoupling”—heavy on U.S. subsidies and restrictions on Chinese imports, investment, and immigration—of the U.S. and Chinese economies. Such actions, Cotton claims, “might dissuade China from its wholesale abuses” and “place us on solid ground for the economic long war that lies ahead.” Easy-peasy. Former U.S. Trade Representative Robert Lighthizer embraced a similar strategy a few days later in the New York Times, criticizing an amendment to the U.S. Innovation and Competition Act that would, if enacted, modestly liberalize restrictions on imports from all countries (not just China) and modestly reform the current process for excluding certain goods from Trump’s China tariffs. According to Lighthizer, by removing some U.S. tariffs (only a few of which target China), the amendment would “make it easier for Chinese manufacturers to take American jobs and keep the United States dependent on China.” By contrast, “to the extent that tariffs might raise consumer prices (which is itself debatable), that is a small price to pay to achieve a strong manufacturing base and secure access to critical supplies.”

It’s all so simple and so very Trumpian, and it’s unsurprising given Cotton’s aspirations and Lighthizer’s legacy. While such criticisms may have worked in 2016, however, they suffer today from a critical flaw: We now have three years of evidence of what an alternative China policy—heavy on tariffs and unilateralism, and dismissive of trade agreements and the WTO—actually produces.

And little of it is good.

Economic Pain for Little Gain

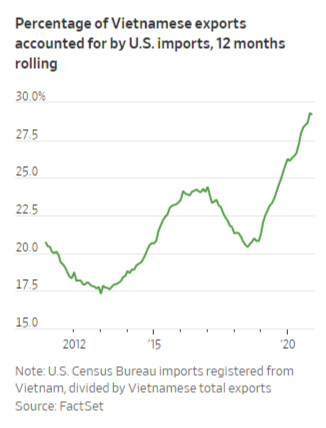

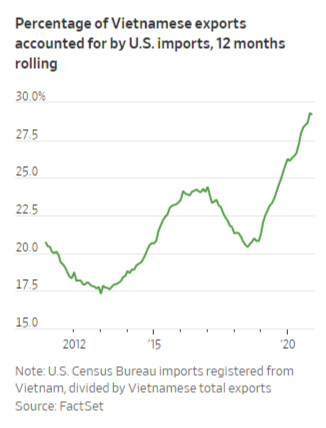

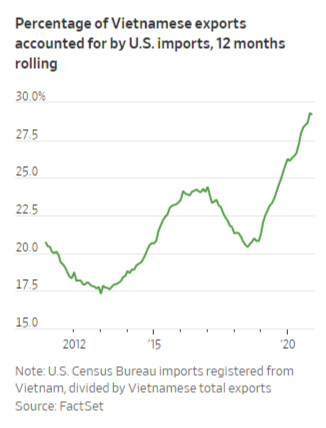

As discussed in previouscolumns, several rigorous academic studies have conclusively demonstrated that the tariffs that the Trump administration imposed on Chinese imports harmed U.S. consumers and manufacturers, deterred investment (mainly due to uncertainty), lowered U.S. GDP growth, and hurt U.S. exporters (especially farmers but also U.S. manufacturers that used Chinese inputs). At the same time, they did little to promote the reshoring of “essential industries” to the United States because global supply chains primarily shifted final assembly of covered goods to other foreign countries, not the USA. For example, Politico’s Doug Palmer reported in February of this year that “as Trump tamped down on imports from China, U.S. companies turned to other foreign suppliers. The U.S. trade deficit with Vietnam, Thailand, Taiwan, Philippines, Malaysia, South Korea, Indonesia, Russia, France, Germany, Ireland, Italy and Switzerland were all higher in 2020 than in 2019.” As the Wall Street Journal’s Mike Bird showed earlier this year, the supply chain shift to Vietnam was perhaps most substantial, fueling the nation’s outsized economic performance:

Mexico was another big winner from this “trade diversion”—which piggybacked on the longer-term shift of certain labor-intensive industries out of China (which has experienced rapid wage growth).

Indeed, a 2019 survey of American Chamber of Commerce companies in China found that “about 41% of American companies are considering moving factories from China because of the trade war, or have already done so, but fewer than 6% are heading to the U.S.” Subsequent data confirm these views: According to a 2020 Goldman Sachs report, “While tariffs did cause rerouting of commodities trade and relocating of consumer electronics production from China to ASEAN countries, we have seen limited evidence of broad-based reshoring of manufacturing activity back to the U.S.”

Despite these supply chain shifts (and China’s self-inflicted damage in retaliating against U.S. imports), American unilateralism’s overall impact on China’s economy has been relatively muted. In an October 2020 paper, for example, economist Yang Zhou found that the “trade war”—covering well more than half of all Chinese exports to the United States—decreased Chinese GDP by only 0.29 percent (about $35 billion). Several factors, almost all of which trade-watchers expected, drove this outcome: First and most basically, the U.S. economy is big but simply not the only game in town—and China still achieved substantial economic growth by continuing (or increasing) trade with other countries. Second, while some U.S. imports of Chinese goods declined, imports of non-tariffed items increased, and, because many of the products subject to Trump’s tariffs weren’t made in sufficient quantities elsewhere, Chinese exporters kept selling them to U.S. consumers, who ended up just eating the additional tariff costs.

Third, many Chinese and multinational manufacturers moved only a fraction of their in-China capacity to other countries, in order to keep serving the large and growing Chinese market or to turn Chinese-made inputs into “originating” content from another country (via complex U.S. customs rules of origin). Finally, the Chinese government adapted its policies quickly to soften the blow for Chinese companies and consumers—including by reducing certain export taxes (to offset U.S. tariffs) or by lowering tariffs on imports from other countries.

As a 2021 report from the Atlantic Council succinctly put it, “After four years, the outcome of the trade war using tariffs is becoming clear: The United States seems to have suffered worse consequences than China.” (Others seem to agree.)

Beyond these economic realities are the trade war’s numerous unintended consequences. As we’ve discussed, for example, overbroad U.S. restrictions on exports of semiconductor equipment to China have exacerbated the current chip shortage. The tariffs helped fuel shortages of medical supplies in the early days of the pandemic. The aforementioned Chinese export tax reductions propelled clothing producer Shein to become “China’s first global fashion giant” (or, as Bloomberg put it, “The very offensive aimed at reining in Chinese dominance has instead helped create a giant”). U.S. hawkishness has likely pushed Chinese students, who provide substantial economic benefits and generally pose a low security risk, to other countries instead (including China, which has previously struggled to retain homegrown human capital). The list goes on and on.

Thus, if the goal of recent U.S.-China trade policy was countering Chinese economic power and boosting both U.S. manufacturing and the economy more broadly, then consider it a failure.

The Geopolitical Mess

Supporters of Trump’s China policy would likely counter the above criticisms by noting that it was less about pure economics and more about geopolitics, but it struggles there, too. As I noted last year, for example, the “Phase One” deal that Lighthizer negotiated is a mess: It alienated allies, encouraged more Chinese economic meddling and U.S. investment there, had no good way to ensure China’s compliance (which most definitely hasn’t occurred), and made many U.S. exporters more dependent on the Chinese market (and thus the Chinese government). Beyond trade stuff, moreover, China’s hardline stances on human rights, Hong Kong, the South China Sea, and other issues have only gotten worse, not better, since the hawks took over.

Indeed, far from bringing Chinese government planners to heel, there are numerous reports that U.S. policy has actually pushed China to double down on self-sufficiency, distortive industrial policy, and nationalism more generally. China’s latest Five-Year Plan, for example “stresses reliance on its own technologies” and “sends [a] defiant message in face of intensifying U.S. sanctions against Chinese firms.” And now Chinese companies are more on board: “a significant consequence of US sanctions is that entrepreneurial Chinese tech companies have abandoned their historic resistance to 'Beijing’s techno-nationalist agenda' and now see their commercial interests as aligned with the government goal of self-reliance.” China-watcher Dan Wang detailed these and other problematic consequences in a recent Foreign Affairs piece (emphasis mine):

Leading entrepreneurial firms can no longer ignore the state’s commands to source products domestically, however. Enhanced U.S. export-control measures have made that decision for them and united China’s government and its leading firms in a shared goal: to pursue technological and industrial self-sufficiency so that no Chinese firm is at the mercy of U.S. trade policies. By imposing restrictions on American products, the U.S. government has inadvertently done more than any party directive to incentivize private investment in China’s domestic technology ecosystem.

Washington is right to target Chinese firms that are obvious military actors or complicit in human rights abuses. But the sweeping nature of the Trump administration’s sanctions did not suggest a careful selection process. Rather, they gave the impression that the United States would punish any Chinese company that achieved success. Chinese firms are no longer sure if they can depend on U.S. products—or if they will be added to another opaque government blacklist and face potential collapse. U.S. export controls have already encouraged other foreign firms to exploit anxieties around U.S. sanctions by marketing themselves as more reliable vendors. And they have created a perverse incentive for some American firms to move production overseas in order to maintain access to China’s enormous market.

U.S. sanctions against Chinese technology companies have deeply offended many in China, especially given their perceived arbitrary criteria and severe effects. Many engineers at top companies such as ByteDance, DJI, and Huawei have studied and worked in the United States and were bewildered by claims that their work constituted a threat to U.S. national security. Chinese officials scratched their heads when the Pentagon declared that the Chinese electronics firm Xiaomi had ties to the military; some joked that Xiaomi was in American crosshairs because the company’s founder, Lei Jun, contained the character for “soldier” in his name. Now that Huawei’s phones are difficult to find in stock, every consumer in China knows that U.S. restrictions have started to bite. It is not unusual, these days, to see people on the Beijing subway watching video explanations of the semiconductor supply chain.

Finally, American hawkishness may have helped unite China with not only other authoritarian regimes like Russia but some traditional U.S. allies, too. The recently completed Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) agreement, which includes China, Japan, South Korea, New Zealand, and several other Asia-Pacific countries, will advance these countries’ supply chain integration and was reportedly motivated by U.S. policy:

Beijing has long been reluctant to sign massive free trade agreements or participate in rule-making in such fields as intellectual property and data transfers. It kept its distance from free trade because it shunned constraints to its policies. But as tensions with the U.S. rise, it conceded to Japan on tariffs so that it could quickly join a trade framework that excludes Washington.

Elsewhere, "tensions in trade relations between the United States and China may have helped change the Chinese position and bring about a deal between Beijing and Brussels" on bilateral investment late last year. Only China’s own actions appear to have delayed the EU deal’s implementation.

So, sure, bag on the (flawed but more effective than you think) WTO and multilateralism all you want, but it’s not like aggressive unilateralism has done any better—in fact, much the opposite.

The Political Dysfunction Along the Way

I’ve already detailed how a more hawkish U.S. policy toward China has, via new subsidies and the aforementioned tariff exclusion system, expanded the size and scope of the government, bred cronyism, and enriched K Street in the process. A subsequent paper on the farm subsidies—cushioning the blow from Chinese retaliation—found clear evidence that they targeted Republican voters (“Trump allocated rents in exchange for political patronage”) and unexpectedly exacerbated political polarization. And porky new U.S. industrial policy subsidies—specifically motivated by China—are on the way.

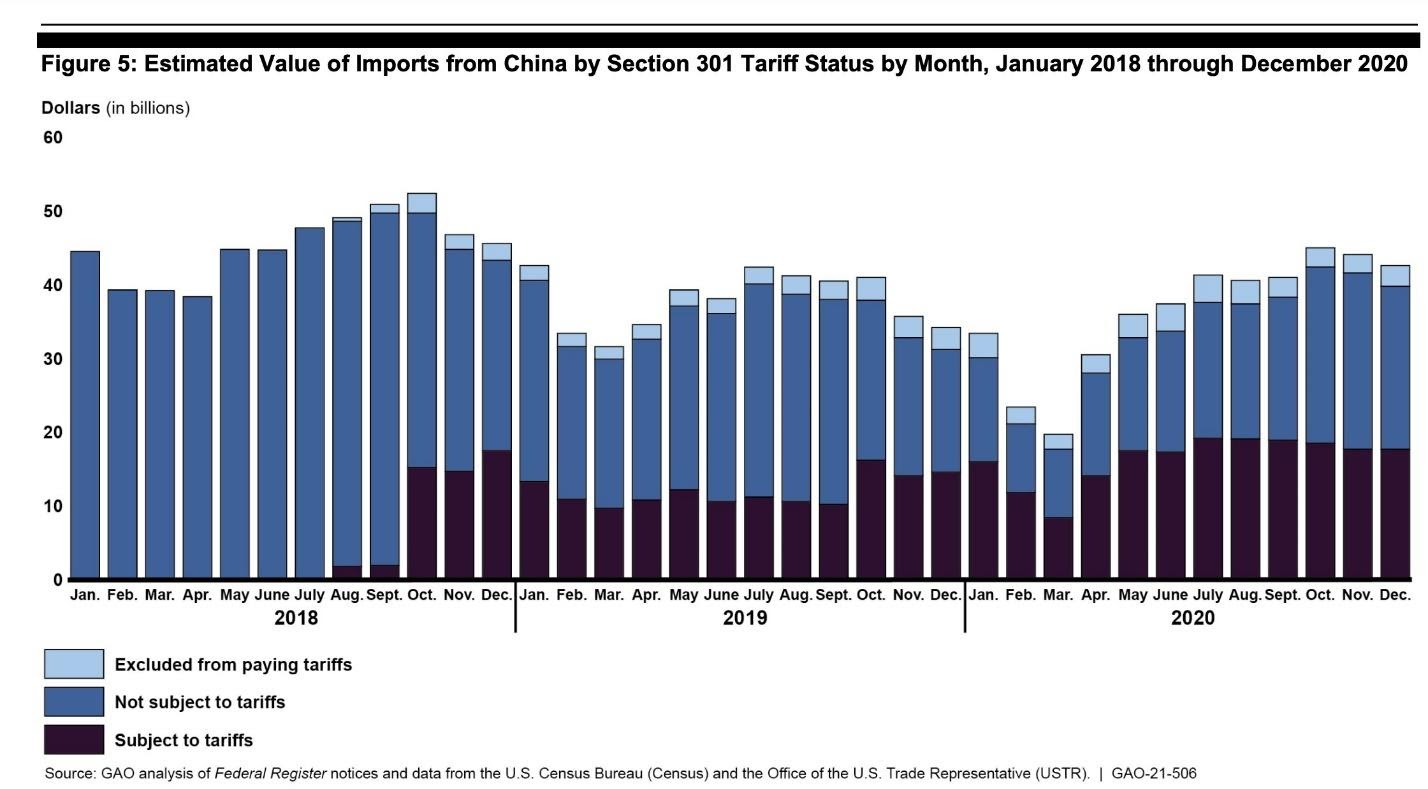

But the exclusion system—which Lighthizer specifically targeted in his new op-ed—warrants additional attention, given a brand new Government Accountability Office report on its Kafka-esque implementation. In particular, GAO found that Lighthizer’s office didn’t fully document its internal procedures for deciding tariff exclusion requests or adequately explain its approval or denial of a request; didn’t document any of its internal procedures for deciding whether to extend tariff exclusions; didn’t have written procedures for the interagency portion of a review; and applied the limited rules it did have in an inconsistent and arbitrary way. ProPublica’s Lydia DePillis summed it up well:

Earlier this year, moreover, DePillis filed her own report on how “Washington’s influence industry, including former Trump officials and allies, has made big money helping companies get exemptions from tariffs — sometimes by undercutting small business owners” in the process.

For Lighthizer to lament in the Times (and for other “conservatives” to echo) that repealing the China tariffs or reforming the tariff exclusion system would enrich “Washington lawyers and lobbyists” may be the new definition of chutzpah.

Summing It All Up

As I’ve discussed here and elsewhere, China undoubtedly warrants criticism and attention from U.S. policymakers, and it represents a major challenge for U.S. economic and foreign policy over the next several decades. There also are, in retrospect, several things that past American policymakers got wrong about China’s trajectory, global impact, and bilateral relations, and President Biden’s “worker-centric” approach thus far leaves plenty to be desired (though it’s still quite early). But Republican critics of past U.S. engagement and the multilateral system more broadly can no longer rely on the vivid imagination of a riled-up base and conservative media to tar their Democratic opponents or sell even more hawkishness and unilateralism in the future. Instead, we now have plenty of evidence—more than three years of tariffs, sanctions, and chest-thumping—of how the “America First” alternative to engagement plays out. And the results are economic weakness, geopolitical mayhem, and a larger, less effective government.

It may be too far to say that—paraphrasing Churchill—multilateral engagement is the worst approach toward China, except for all the others that have been tried. But compared to the last few years, it’s looking pretty darn good right now.

Chart(s) of the Week

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.