Hi and happy Sunday.

Paramount in so many conversations about religion’s role in the public square these days seem to be understandings of both justice and mercy—and how to balance them. Take immigration, understandings of human sexuality, or the use of the death penalty—just to name a few.

Author Karen Swallow Prior argues this week that the West’s rich history of virtue ethics can inform those conversations and understand the proper way to employ some virtues—seemingly in tension—at the same time.

Karen Swallow Prior: The False Battle Between Justice and Mercy

A minister begs a leader to show mercy toward outcasts and is accused of having “toxic empathy.” A politician argues that rightly ordered love demands we take care of those closest to us before giving to those further away, and the pope himself offers a correction. A failure of justice leads to the murder of an innocent young woman, and neither justice nor all the compassion in the world can bring her back.

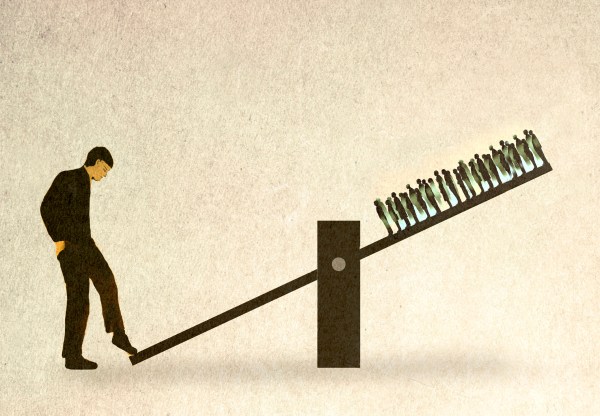

If you were to base your understanding of mercy and justice on reading recent headlines, you’d get the distinct impression that they are two teams competing in a cosmic Super Bowl and the rest of the world is just placing bets, with one winner taking all.

But the countervailing demands of the virtues of justice and mercy do not present a zero-sum game. Justice without mercy is not just. Mercy apart from justice is not merciful. If we understand the nature of virtue in general—particularly by considering the long tradition of virtue ethics set out by Aristotle, Aquinas, and modern philosophers such as Josef Pieper and Alasdair MacIntyre—we can better understand how these particular virtues are mutually dependent, and how we can achieve one only when we achieve the other.

A virtue consists of the proper balance of a particular quality between its excess and its deficiency, and a vice is too much or too little of an otherwise good quality or characteristic. Too much confidence, for example, is the vice of vanity. Too little is the vice of timidity. Healthy pride embraces the human dignity that belongs to us all. Lack of effort is sloth, and too much effort is frenzy, but moderation between these two extremes achieves the virtue of diligence. A lack of courage is the vice of cowardice. An excess of the same quality becomes brazenness or recklessness. Doing harm through recklessness, even in the process of attempting to do good, fails the test of courage. Similarly, justice and mercy require avoiding both excess and deficiency.

Mercy means compassion. It moderates between the excess of permissiveness or over-indulgence and the deficiency of apathy or lack of empathy. Mercy gives us what we don’t deserve, but only true justice can tell us what that is. Justice means fairness. It moderates between selflessness (having less than one’s share) and selfishness (having more than one’s share). Where justice is deficient, it enables more harm. Where it is excessive, it becomes the vice of vengeance or injustice.

Since justice means that everyone gets what is due to them, desiring it requires actually caring about others. And caring requires the virtues of compassion and empathy. Thomas Aquinas observes that excessive punishment, an outward act, actually derives from inward the vice of cruelty—in other words, lack of mercy or empathy.

Thus the two virtues of mercy and justice—and their corresponding vices—are inextricably connected. They are like two sides of the same coin. They naturally balance one another. Moreover, virtue ethics teaches that no good quality remains virtuous if it is severed from the other virtues. Diligence is a vice when done in service of evil rather than good. Loyalty toward an evildoer is not a virtue; it is the vice of complicity. So, too, both justice and mercy must be oriented toward the good in order to be virtuous.

The fulfillment of this delicate proportion of justice and mercy is a central teaching of Christianity. The Bible is replete with admonitions to pursue justice and to be compassionate and merciful. Religious leaders confronted Christ for breaking the religious laws in acting mercifully. But Christ explained to his followers that he came not to abolish those laws but rather to fulfill them, which required both justice and mercy. Justice was fulfilled when, as Christians believe, he offered his life as a sacrifice to atone for the sins of others—he paid the penalty that was due. But that in itself was merciful to those who believe in his sacrifice. This teaching fully embraces the tension between justice and mercy yet perfectly balances the two. It makes sense then that so many Christians have been vocal and invested in public conversations and political policies connected to the virtues of justice and mercy. But of course, justice and mercy are demands made by all religions, placed on all people and all societies.

Simply knowing proper definitions won’t in itself help us to achieve these virtues, of course. But knowing what they are—and what they are not—orients us in the right direction. Nor do definitions of the virtues of justice and mercy offer exact formulas for what is fair or merciful in any given situation. Determining that is the real work. And it is that work—that practice, that habit, that way of being—that cultivates virtue in each of us as individuals and in our society. We will never achieve perfect virtue, but the more we pursue and practice it, the more virtuous we become.

Shakespeare grappled with these questions brilliantly in The Merchant of Venice, a play that demonstrates just how difficult it can be to address the claims of both. Near the end, Portia has disguised herself as a man to pose as a lawyer in court to argue on behalf of the defendant who will lose his life if the plaintiff, Shylock, collects what is legally due him. In arguing for mercy rather than justice, Portia offers a memorable soliloquy about mercy:

The quality of mercy is not strained;

It droppeth as the gentle rain from heaven

Upon the place beneath. It is twice blest;

It blesseth him that gives and him that takes:

‘T is mightiest in the mightiest; it becomes

The throned monarch better than his crown:

His sceptre shows the force of temporal power,

The attribute to awe and majesty,

Wherein doth sit the dread and fear of kings;

But mercy is above this sceptred sway;

It is enthronèd in the hearts of kings,

It is an attribute to God himself;

And earthly power doth then show likest God’s

When mercy seasons justice.

Portia links mercy with the power and character of God and suggests that when the balance between mercy and justice must tip, it is more godly to lean that balance toward mercy.

Because it is the villain in the play who demands justice, it would be easy to misread the play as offering a simple, black and white picture of justice vs. mercy. But Shakespeare presents a much more complicated—and realistic—portrayal of the competing and complex demands of justice and mercy. Shylock, an outcast Jew, is the first in the play to have been the recipient of cruel injustice. And the “mercy” Shylock receives for his own treachery—not only forgiveness but a forced conversion at the hands of a Christian state—is an imperfect form of mercy in the end. But it is one of Shakespeare’s gifts to us to offer dramas that help us cultivate virtue by seeing truths his characters couldn’t see.

As Shakespeare poignantly shows, it is exceedingly hard to get this balance right. But he also shows—in depicting the long-term persecution of Jewish people in Europe, personified by the suffering Shylock—that failing to get it right has ripple effects for generation upon generation.

Because neither true justice nor compassionate mercy can exist apart from the other, we cannot really talk about one apart from the other. Nor, perhaps, should we listen to those who call for one and not the other.

We may disagree on what constitutes justice or mercy in any situation, but we ought to be able to agree that we cannot achieve one without the other.

More Sunday Reads

- Earlier this week we published reporting from Senior Editor John McCormack on the Trump administration’s newfound antipathy toward religious groups, at least those working in the realm of immigration. As John reports, the first Trump administration and congressional Republicans previously seemed supportive of the same groups and initiatives they’ve recently come to vilify. “Indeed, the federal government has been asking religious nonprofits to care for unaccompanied minors for decades. The Trafficking Protection Victims Act, passed in 2000 and reauthorized in 2008, establishes special protections for minors who arrive from countries that do not share a border with the United States. Under that U.S. law, minors from Canada and Mexico may be quickly deported if there are no signs of trafficking, but the removal process for minors from other countries goes through a lengthier adjudication. Sometimes the government relies on nonprofits to shelter, feed, and educate those unaccompanied minors, or help reunite them with their family members. If the children are allowed to stay, the Trafficking Victims Protection Act requires home studies to ensure those minors are going to a safe place, and the government often relies on religious nonprofits to do that vetting. During Trump’s first term, his administration gave hundreds of millions of dollars to secular and religious groups to care for unaccompanied minors, and Melania Trump visited one of the Lutheran charities caring for unaccompanied minors in 2018. When the arrival of unaccompanied minors first reached crisis levels during the second term of the Obama administration, Republicans viewed religious nonprofits as part of the solution to the humanitarian crisis. ‘I want to thank Catholic Charities that are working to care for these children and care for these families,’ Texas GOP Sen. Ted Cruz said during a 2014 visit to McAllen, Texas.” John caught up with Cruz recently and tried repeatedly to press him on his views of such groups now. “Asked a second time if he now thinks charities are a cause of the border crisis, Cruz said before stepping into an elevator: ‘There are more than a few NGOs that were actively complicit in the invasion of our Southern border, and it is why it is Democrat policy to funnel billions to the NGOs where in many ways Joe Biden and Kamala Harris were the last mile of the human trafficking network that resulted in such egregious abuses.’”

- Part of the zeitgeist for some religious writers on the right has included a questioning of the so-called “postwar consensus” that has shaped moral and political commitments in the West since World War II—such as the concept of universal human rights. Critics of the postwar consensus, such as First Things editor R.R. Reno, have argued that its commitment to ideal such as secularism undermines the whole project. But in the journal Ad Fontes, John Ehrett argues that much of the postwar consensus—while by no means perfect—sprang from Christian thought seeking to correct errors made by Christians rationalizing the horrors of fascist regimes. He does so by mining both contemporary arguments against the postwar consensus and writings of German Christians seeking to make their peace with the Third Reich: “To connect the dots: on this account, God’s will becomes coterminous with the will of the political collective, with the collective’s striving toward a common end. That is a theological problem. It is a problem which follows from confusing, tacitly, two different conceptions of that which is divine: transcendent authority, and the bond by which the collective coheres. The deep theological ambivalence of this latter—the-sacred-as-collective-effervescence—is something which the ‘postwar consensus’ rightly reacted against at the level of principle. In Christian terms, absolutizing the latter sacred can (and did) lead to idolatry: divinizing, as the ‘Will of God,’ a particular constellation of historically contingent Völker, and denying any possibility of exit or critique. This was not the faith for all once delivered to the saints. Construing Nazism (and the German Christian movement, and its sympathizers) as a specifically theological problem can help explain why, in the postwar period, so many players understood the emergence of the postwar consensus in specifically Christian theological terms—as a theological correction of deficient theology. It may come as a surprise to those highly invested in denouncing the ‘postwar consensus’ today, but as legal historian Samuel Moyn has recently argued in great detail, the regime of ‘human rights’ so basic to this postwar consensus was, in fact, elaborated as an integrally Christian project—as a response to the way in which Nazi ‘theology’ went awry.”

- Reports of young people turning to older Christian traditions such as Eastern Orthodoxy and Roman Catholicism have been part of the recent milieu, but for Religion News Service, Richa Karmarkar writes that similar occurrences are happening with Hinduism. “Amid confusing times, says devotional musician Gaura Vani, Generations Z and X have found a way to articulate their complicated emotions and feelings through the call-and-response style of kirtans, the devotional songs commonly associated with the Hare Krishna faith. ‘This is almost a miraculous thing to say, but in this world of social media and phone addiction and all that, the kids in the Krishna community are doing the craziest thing: Without anyone telling them to, they will find a weekend where everyone’s free, they will dress to the nines together, and find a temple or a space where they will do kirtans for, like, 10 hours straight,’ he told RNS. ‘It’s crazy. It makes no sense in the modern world, but they’re doing it.’”

A Good Word

For The Pillar, Filipe D’Avillez profiles a Christian tattoo shop, Razzouk, that has operated in Jerusalem for hundreds of years in a story that underscores the complexities for so many communities in the Holy Land. “Razzouk’s roots date back to 1300, in Egypt, and is still in the hands of the same Coptic Orthodox family whose ancestors came on pilgrimage to the Holy City, centuries ago. These days, the family’s patriarch is Anton Razzouk. At 84, Anton no longer tattoos, but the family art continues with his son Wassim and his nephew Chris. … ‘We are Copts, originally from Egypt, and our ancestors who first came to Palestine came on pilgrimage. At that time, one would come for a long time, perhaps even a year, so they had to work while they were here. My forefathers knew how to make tattoos,’ he tells me, in reference to the longstanding tradition that Copts have of tattooing small crosses on their wrists. Razzouk is — and has been for centuries — the preferred destination for pilgrims who want a permanent reminder of their trip to Jerusalem.” The tattoos his family creates are “keys to heaven,” Anton told D’Avillez. “‘What do I mean by a key to heaven? When you have a Christian tattoo, let’s say a Jerusalem cross or a Coptic cross on your palm or on your wrist, this can be a sign that reminds you not to sin. Suppose you have an enemy and you want to slap him, or somebody disturbs your peace, and you want to hit him, or defend yourself. Seeing your Cross is a reminder of the commandments.’”

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.