I promise that I’m going to move on from the American race debate soon, but not today—in part because I’m morbidly fascinated by the debate’s relentless dysfunction. On the right it often seems that if we can effectively rebut the radicals, we act as if our rhetorical work is done. Debunk critical theory, reject various definitions of systemic racism, and then move along. Back to business as usual (with the conventional and obligatory “to be sure” paragraphs noting that a few racists still haunt American life).

As for the left? Well, one of its principal and most prominent recent projects about American history actually tried to claim that the advent of slavery into the American colonies represented the “true founding” of the United States of America. Moreover, the relentless intolerance spawned by the “Great Awokening” is driving even mainstream progressives out of (formerly) liberal institutions. Illiberalism is on the rise, and much of that illiberalism is rooted in a radical, quasi-religious anti-racist ideology.

Then the dysfunction is compounded by the fact that in the world of journalist and academic racial discourse, the definition of words themselves is up for debate. “Racism” is a contested term. “White supremacy” is a contested concept. And who the heck even knows what “systemic” is supposed to mean?

So I thought—in concluding this round of French Press commentary on race in America—I’d back up a bit, shed the buzzwords as much as possible, reject the extremes, and see if we can begin to formulate any consensus at all around a few, basic ideas.

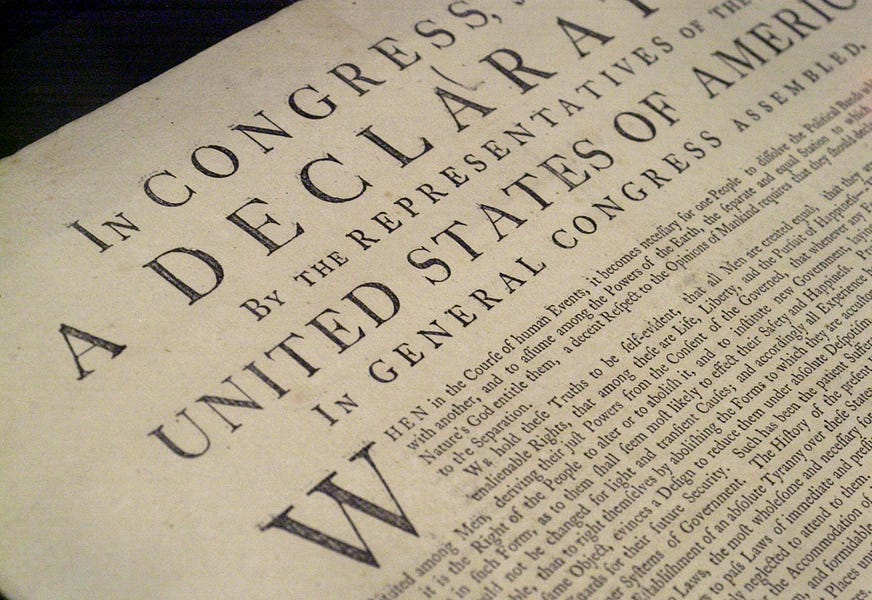

First, contrary to the revisionists, 1776 still represents the “true founding” of the United States of America. As I recently argued in the pages of National Review, when the first slaves arrived in the New World in 1619, it signaled not the founding of something new, but rather the reaffirmation of something very, very old—the same oppression and domination that characterized human history from the dawn of time.

When the Founders ratified the Declaration of Independence (and later the Constitution and Bill of Rights), they created something new—a civilization centered around the aspiration of human liberty and dignity. At this early stage, the idea of America contradicted most of the reality of America, but the idea had startling, resonating power.

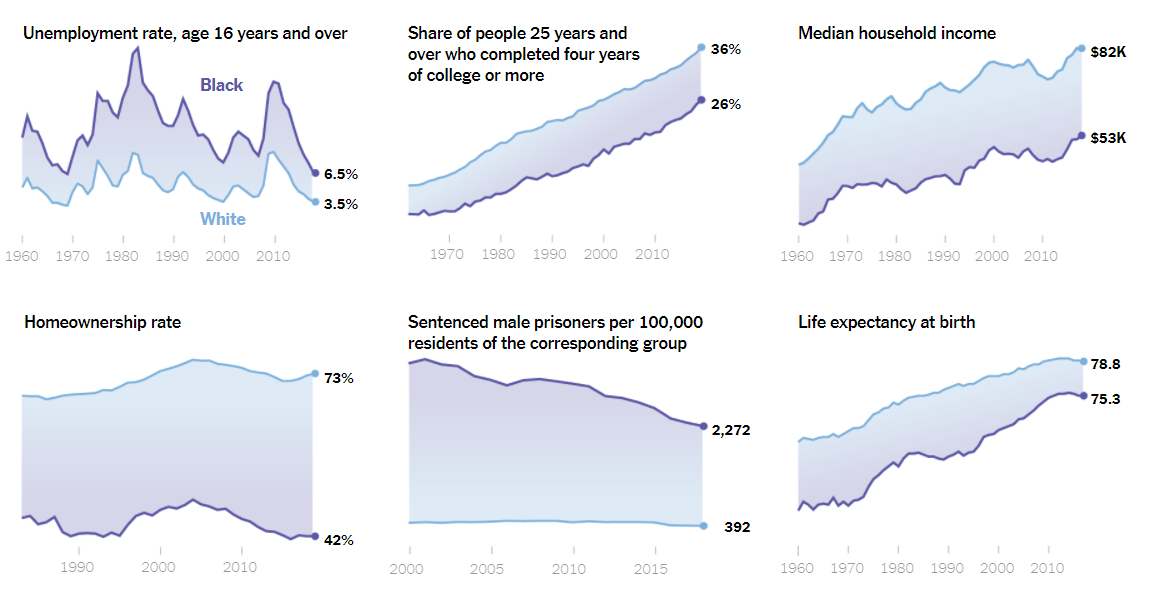

Second, much of American history consists of the contest between the old oppression of 1619 and the new liberation of 1776—during which the liberation of 1776 slowly and steadily prevailed. Here in 2020— post-slavery, post-Jim Crow, and recently removed from two terms of the first black president of the United States of America— not only is it quite clear that there has been enormous racial progress in the U.S., it’s equally clear that much of that progress was made by directly appealing to American ideas and principles of the American founding.

Third, just as the contest between 1619 and 1776 consisted of competing ideas, it also consisted of competing systems. The systems of 1619 are clear enough—slavery, Jim Crow, redlining, segregation. These systems didn’t just treat black Americans as property, they denied generations of black Americans equal access to education, economic success, and—crucially—the generational wealth accumulated through centuries of economic freedom and prosperity.

But the principles of 1776 created their own systems, including legal and cultural institutions that provided consistent critiques for the systems of 1619 and also formal instruments of raw power that broke the back of the legalized repression and discrimination. The Union Army broke the Confederate Army. The judiciary, the Department of Justice, and Congress broke segregation and Jim Crow. The judiciary to this day—empowered by the Constitution and the Civil Rights Act—continues to break apart formalized systems of discrimination and bigotry.

Fourth, unfortunately broken and breaking systems can still leave powerful, enduring legacies. If you take any population of human beings, treat them as property for 245 years, actively, legally, and violently discriminate against them for 99 more, and only give them the necessary legal tools to effectively fight back 56 years ago, then you’re going to still see significant consequences—and those consequences are going to be very hard to ameliorate.

I was interested to see that a number of readers commented on my Sunday newsletter about the disparities between the disproportionately white, rich private school I advised and the nearby much-poorer, disproportionately black public school down the road and said that the relevant difference was wealth, not race. But when you’re talking about a community that was afflicted by all the systems of 1619 (including within the lifetimes of thousands of residents), why would anyone think that wealth disparities would vanish by 2020—or that the racial history that created the initial disadvantage would no longer be relevant?

If your economic starter pistol goes off after your neighbor’s—and they’re also running as fast as they can to achieve prosperity—doesn’t it stand to reason that even as you run as hard as you can, the gap might persist? And isn’t that largely the tale of the tape in black/white income and wealth disparities?

None of this is an argument that black families haven’t made enormous strides (look at increases in college degrees, household income, and life expectancy)—and nor is it an argument that any given black American can’t leapfrog over everybody to achieve wealth and success—but it is an argument that centuries of actions at the very least can have decades of consequences.

Fifth, the fact that many, many American institutions still struggle with the legacy of 1619 does not render those institutions presently racist. This is exactly the point where millions of American get upset about allegations of current, systemic racism. They belong to institutions that work very hard to address historic imbalances, and the fact that any given college or company can’t create a community that’s free of the consequences above is not proof that the college or company is racist or shot-through with white supremacy.

(For example, so long as achievement gaps exist, how many colleges or corporations are truly able to ramp-up admissions or hiring to create a workforce that would exist had 1619 never happened?)

Instead of their institutions being in the grips of “systemic racism,” the actual system many Americans live and work in is affirmatively anti-racist. There might still be racist individuals within that system (indeed, there often are), but the system itself is working against white supremacism and white nationalism, sometimes in heavy-handed and radical ways. (See, for example, college speech codes.)

This is where our national inability to agree on terms and meanings gets frustrating and destructive. The ordinary person hears the phrase “systemic racism,” and the plain meaning of the words constitute an allegation that the system they’re presently a part of is affirmatively racist. Yet that allegation defies everything about their experience. They’re not racist. They hate racism. Their company is anti-racist. They’re on the side of 1776, and they rightly reject radical claims that their institutions are full of hidden hate and unconscious malice.

At the same time, other folks say the phrase “systemic racism” and primarily refer to the systemic effects of centuries of racism. They’re referring to the persistent distortions of human experience and the human condition resulting from the legacy of 1619.

Finally, our emphasis on systems should not disempower individuals. We’ve made immense progress. Our nation provides great opportunity to countless millions of Americans of every race, creed, or color. Systems can create disadvantages. History can create obstacles. But we’ve seen too many examples of incredible achievement in the face of adversity to speak to young Americans of any race and counsel despair.

The bottom line is that the light of 1776 is overcoming the darkness of 1619. Yet in our broken discourse there are Americans who deny that light. They see only darkness. And, conversely, other Americans have lived in the light for so long that their eyes fail to see the shadows that still persist.

One more thing …

I’m starting to get the first reviews on my new book, and I must say that The Gospel Coalition’s Collin Hansen gets me. I feel seen. He walks readers through last summer’s Ahmari/French wars, then writes this:

There’s an appealingly simplistic logic to Ahmari’s argument. Drag Queen Story Hour is a bad idea, and conservatives should seek and deploy the coercive force of the government to stop it. French’s book teases out the implications of this logic for the American Republic. But any power you can wield against your ideological enemies, they can wield against you once they gain power. The more power the government holds, the more desperately each side seeks it. The more desperate each side grows, the more likely they are to use real bullets in the culture war. At some point, unless you’re willing to kill and be killed, you need to live and let live.

That last sentence is fantastic. I wish I’d thought of it. The book comes out next week! Pre-order here.

Two last things …

First, this video, of the San Francisco sky set to Blade Runner music, is chilling. God bless the people of California:

And second, tomorrow I’m going to participate in a discussion with Irshad Manji and Rabbi Lord Jonathan Sacks that tries to answer the question, “Does democracy need religion?” Details below!

No, really, here’s the truly last thing …

I finished the newsletter yesterday evening before this happened—one of the greatest clutch blocks in NBA history. Astounding. Oh, and you need it in multiple languages:

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.