If I had to summarize a complicated, important week at the Southern Baptist Convention’s meeting in a single sentence, it would be this: In a series of contentious confrontations, the nation’s largest Protestant denomination confirmed that it is (for now) more Evangelical than fundamentalist. And that outcome is good news for the church and the nation.

To explain what I mean, let me back up a moment and define my terms. It’s important to understand what “Evangelical” really means, and that requires going back to pre-exit poll Christianity.

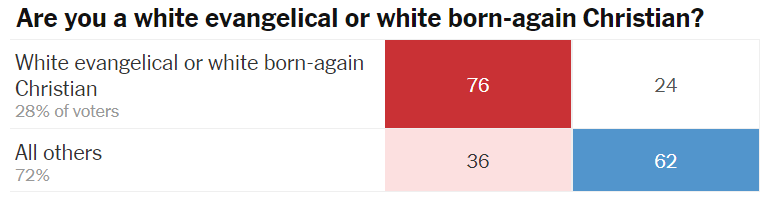

How did exit polls corrupt our definitions? When most Americans think of the term “Evangelical,” they’re not thinking so much as a set of theological presuppositions but rather of the sub-group of Americans who respond “yes” to an exit-poll question, a very imprecise exit-poll question. For example, here it is, in 2020:

The problems with the question are obvious. Immediately you lose any sense of the racial diversity of American evangelicalism. Black and Hispanic Evangelicals are lost in “all others,” and they’re far more politically diverse than white Evangelicals. In addition, the question papers over tremendous differences within “evangelical” and “born-again” Christianity itself.

Thus, the word “Evangelical” became primarily a political category, obscuring the historical meaning of the term and eradicating a distinction that is still deeply salient within American Christianity—the cultural, theological, and political difference between evangelicalism and fundamentalism.

I grew up in fundamentalism. I converted to evangelicalism. The difference is profound but often opaque to those who are outside the “born again” (rather than Mainline) Protestant tradition. After all, both the fundamentalist and Evangelical branches of “born again” Christianity believe in the authority of scripture. Both branches are generally politically conservative. That’s why it’s just wrong to frame the differences between the two as “right versus left” or “conservative versus liberal” or much less as a battle between “conservative versus ‘woke.’”

Instead, I’d frame the difference in a number of different ways—“grace versus law,” or perhaps “open-hearted versus closed-minded.” In an earlier newsletter, I described fundamentalists as possessing “fierce existential certainty.” The fundamentalist Christian typically possesses little tolerance for dissent and accepts few sources of truth outside of the insights that can be gleaned directly from the pages of scripture.

As I’ve argued before, I don’t think you can understand the far-left or the far-right without understanding fundamentalism:

Far-left fundamentalism often manifests itself in the illiberal zeal of the so-called “Great Awokening.” It’s a secular version of the religious intensity of the far religious right, rejecting alternative worldviews with the same ferocity that religious fundamentalists reject secular sources of truth.

You can often distinguish fundamentalism by its emphasis on righteousness and its obsession with the idea that compromise anywhere is compromise everywhere. That’s a key reason internal arguments are so ferocious. Give an inch on young earth creationism, and you’re abandoning scripture. Give an inch on, say, the “the extent to which we can benefit from secular psychology in biblical counseling,” and you’re declaring that scripture is insufficient as a guide for life and faith.

Because compromise is so catastrophic, fundamentalism often manifests itself in Christian politics through a series of moral panics, where issues assume apocalyptic importance. Teach evolution in schools, and we’ll face God’s wrath. God abandoned our nation when we lost school prayer. Gay marriage is the point of no return. Critical race theory threatens the foundations of the church and the republic.

Evangelicals will often share the fundamentalist’s cultural concerns (which is why the distinction between fundamentalism and Evangelicalism is often opaque to those outside the church), but not their political or cultural intensity, nor their apocalyptic fears. Evangelicalism more readily embraces doubt and difference. It is more open to sources of knowledge outside the church.

To stick with the critical race theory example for a moment, the Southern Baptist Convention’s 2019 Resolution 9 on CRT and intersectionality is a classically Evangelical document. It states that “general revelation accounts for truthful insights found in human ideas that do not explicitly emerge from Scripture.” Yet it also declares the truth that “critical race theory and intersectionality should only be employed as analytical tools subordinate to Scripture.”

In other words, while there are things Christians can learn from critical race theory, scripture is still supreme. When CRT conflicts with scripture, then scripture rules.

The fundamentalist rejects this framework. Just as with secular psychology, secular concepts like CRT—springing often from non-Christian scholars—are deemed corrupt to their core. There is nothing we can learn from them that we can’t learn by applying scriptural principles, and thus must be rejected, root and branch.

Moreover, in part because Evangelicals are more comfortable with doubt and difference, they’re often more ecumenical and less prone to see doctrinal differences as dealbreakers for cooperation and fellowship. My introduction to evangelicalism, for example, occurred at my law school Christian Fellowship, where Baptists worshiped side-by-side with believers from virtually every Protestant denomination and tradition.

In my fundamentalist upbringing, many of our leaders wouldn’t have labeled that gathering “Christian.” They would have labeled it a misbegotten fellowship of the lost.

Few fundamentalists are quite that exclusive now, but you can see why fundamentalists often express a deep discomfort with pluralism and experience a constant sense of emergency. Someone is always pulling on a thread of the faith somewhere, and pull hard enough on any thread, and you risk unraveling the entire fabric. Political disputes assume outsize importance. Political differences become intolerable.

Evangelicals often also have a higher view of grace than fundamentalists. They emphasize God’s grace more than God’s rules and are more prone to focus on God’s mercies than God’s judgment.

To see the difference, I’m going to quote below one of the most famous passages in all of scripture—the story of the woman caught in adultery—and I’m going to bold the most salient words to the Evangelical and italicize the most salient words to the fundamentalist:

But Jesus went to the Mount of Olives. Early in the morning he came again to the temple. All the people came to him, and he sat down and taught them. The scribes and the Pharisees brought a woman who had been caught in adultery, and placing her in the midst they said to him, “Teacher, this woman has been caught in the act of adultery. Now in the Law, Moses commanded us to stone such women. So what do you say?” This they said to test him, that they might have some charge to bring against him. Jesus bent down and wrote with his finger on the ground. And as they continued to ask him, he stood up and said to them, “Let him who is without sin among you be the first to throw a stone at her.” And once more he bent down and wrote on the ground. But when they heard it, they went away one by one, beginning with the older ones, and Jesus was left alone with the woman standing before him. Jesus stood up and said to her, “Woman, where are they? Has no one condemned you?” She said, “No one, Lord.” And Jesus said, “Neither do I condemn you; go, and from now on sin no more.”

Evangelicals and fundamentalists both believe every word of the scripture above, but the Evangelical pastor will often emphasize that while sin is real, no sin is beyond the grace of God. The fundamentalist pastor will often emphasize that while grace is real, don’t doubt for a moment that God hates sin. “Sin no more” were the last words, and thus the core operative command.

Is this too much background? Not at all! There’s one last thing—while fundamentalist influences wax and wane in born-again Christianity (indeed, in most faiths), they often grow in strength in times of social conflict and cultural upheaval.

Do you wonder why legalistic “purity culture” grew in influence in the 1990s? Buffeted by the sexual revolution, families sought certainty and security. Purity culture beckoned with a clear, easy-to-understand path to righteousness and a (presumed) formula for a healthy, happy marriage.

Moreover, the emphasis on single issues and big battles appeals to a certain “hold the line” heroic mindset. It speaks to the heart of those who are drawn to strong stands and dramatic fights. At the risk of nerding out, think of Captain Jean-Luc Picard in this famous dialogue in Star Trek: First Contact:

Before the SBC meeting, perhaps the most insightful preview of the coming conflicts came from my friend Trevin Wax. He identified three big questions that divide Baptists:

Do Southern Baptist churches unite primarily around doctrinal consensus or missional cooperation?

Should we engage secular sources of knowledge with a fundamentalist or an Evangelical posture?

How politically aligned must Southern Baptists be in order to cooperate together?

Note how each either explicitly (in question 2) or implicitly centers around the fundamentalist/Evangelical divide. And how were those questions answered? In virtually every case, the SBC took the Evangelical approach.

First and foremost, in its presidential election, it rejected the more-fundamentalist, culture war candidate of the far-right Conservative Baptist Network, Mike Stone. It also rejected Al Mohler, the legendary head of the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary. Mohler isn’t just a seminarian, he’s a leading cultural commentator who consistently takes on the left in matters large and small.

Instead, the convention narrowly elected Ed Litton, a man known far more as a pastor than a culture warrior and who is also known for his efforts at achieving racial reconciliation within the SBC. It also left Resolution 9 intact, failed to adopt any clear condemnation of CRT, and it watered down a pro-life abolitionist resolution that would have wholly rejected any incrementalist approaches to ending abortion.

To understand the magnitude of these votes, black SBC pastor Dwight McKissic tweeted this (he had previously threatened to leave the denomination):

In short, as I wrote last week, fundamentalist Baptists charged into Nashville behind pirate flags pledging to “take the ship.” They failed.

The reasons are many and complex, but this explanation—also from Pastor McKissic—resonates:

It’s also true that leaders like outgoing president J.D. Greear courageously stood and fought, with the conviction all too many fundamentalists claim that Evangelicals lack, for an inclusive SBC that is dedicated to racial reconciliation, abhors sexual abuse, and rejects political litmus tests:

Greear called on white Southern Baptists to “stand with their brothers and sisters of color as they strive for justice.”

He also implored Black and Hispanic pastors not to give up on the denomination as it works through its struggles.

“To our leaders of color, many of you are struggling to stay in a convention you think cares little about you: we need you,” Greear said to a standing ovation. “There is no way we can reach our nation without you.”

More:

Greear also lamented the reputation the SBC has gained as a political organization.

It’s never good when that happens, he explained. “Anytime the church gets in bed with politics, the church gets pregnant, and the offspring does not look like our Father in heaven.”

And he decried not just partisan litmus tests but also the cruelty of political combat:

The exaggeration and lies many of our entity leaders have had to respond to, it makes us smell like death even when our theology is squeaky clean. I hear from Latinos and African Americans wondering why they would want to be part of this fellowship.”

It has to stop, he said. “We are great commission Baptists. We have political leanings. But we are not the party of the elephant or the donkey. We are the people of the lamb.”

The SBC not only reconfirmed its commitment to racial unity, it also took a decisive stand against sexual abuse. The “messengers” (delegates) to the convention decisively rejected the Executive Committee’s attempt to control the investigation into allegations the committee mishandled allegations of sexual abuse.

Instead, as Baptist News reports, they voted to “wrest control of the already announced investigation from the Executive Committee and put it in the hands of a task force to be named by new SBC President Ed Litton.”

That vote lead to a powerful moment—when survivors of sexual abuse embraced after years of courageous advocacy. At long last, transparency and accountability seemed possible:

The SBC meeting represented a victory—especially for those who (to quote one Baptist pastor) hoped to see the convention become “conservative in our convictions but liberal about our love.” But it’s a victory in a battle, not the conclusion of the war. The closeness of the presidential election was a symbol of the strength of fundamentalism, and further cultural conflict and cultural upheaval may strengthen it more still.

But J.D. Greear is right—no church should define itself as the “party of the elephant or the donkey,” and the more that any church does, the more that political disputes will assume apocalyptic importance, the more that American intolerance will grow, and the more that Christians will confuse the pursuit of the biblical justice (which every Christian should seek) with the pursuit of Christian power, which history has shown is often wielded in oppressive and punitive ways.

A healthy American culture needs a healthy church, whether that church leans left or right. As John Adams famously declared, “Our Constitution was made only for a moral and religious People. It is wholly inadequate to the government of any other.”

He knew that “religious” did not always imply “moral.” By standing with victims of sexual abuse, by defeating the effort to turn the SBC into an adjunct of a thoroughly Trumpist GOP, and by standing against racial division, in a crucial moment the SBC gave the nation hope that a commitment to a faith carries with it a commitment to morality, and that morality can be centered in both justice and grace.

One more thing …

I want to show you concretely what it means to differentiate between open-hearted evangelicalism and furious fundamentalism in American politics—and to show that while a battle was won, the war rages on.

First, here’s Dana McCain at the SBC, speaking about her pro-life convictions with courage and with compassion.

Next, here’s the apocalyptic rage of intolerant, illiberal Christians on full display while they vent their fury at a former vice president whose “sin” was drawing the line at destroying the republic in his service to Donald Trump:

In the collision between these worldviews, I know exactly which one needs to prevail.

One last thing …

Ok, this is an old classic, but JJ lives in my neighborhood, and I ran into her just the other day. She and her husband are delightful folks, and this song is just a wonderful expression of the grace that drew me out of fundamentalism and into the faith is centered around the marvelous mercy of the cross:

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.