Dear Reader (including you incredibly ambitious hydro-podders),

One of my favorite thought experiments is, “What if we found out that dolphins were sentient?” We figure out a dolphin-to-human translator and discover they’re basically as smart and self-aware as we are. Yes, I probably got the idea from Day of the Dolphin and Ed Lutwack’s 1993 essay “If Bosnians Were Dolphins.” What would our societal reaction be? What would the pope say? Would we give dolphins rights? Would nations recruit dolphins as underwater assassins? Would there be truth commissions to deal with the moral problems of all that non-dolphin-safe tuna-fishing? What mischief would the trial lawyers get up to?

But that’s a topic for another day.

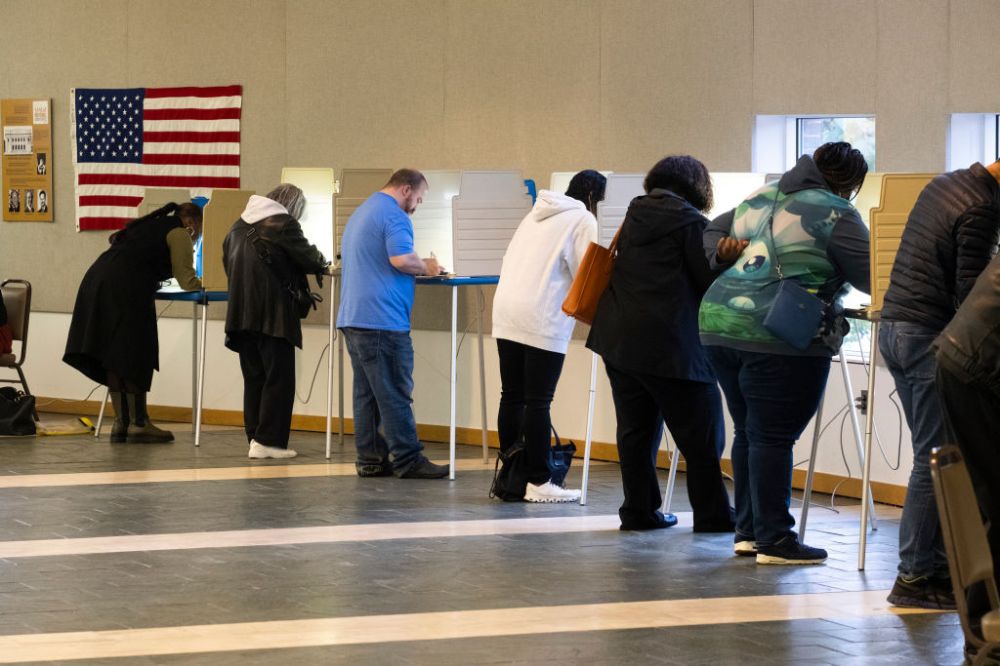

Another of my favorite thought experiments is, “What if voting were mandatory?” This is a more practical question, not least because there are lots of people who support the idea. I’m so intrigued by the idea, I’ve written a few columns on the subject.

Now, as a constitutional and philosophical matter, I still don’t like the idea. Compelled voting is like compelled speech. And such compulsion is, in the words of Lord Acton, “icky.”

For me, the primary appeal of this idea is that it would dispel any number of myths, often most dearly held by advocates of mandatory voting. For generations, many on the left have convinced themselves that if everyone voted, Democrats—very left-wing Democrats—would benefit. I think this idea goes back to the Myth of the General Strike, which held that if everyone stopped working, capitalism would come crashing down and the masses would get to divvy up the spoils. I don’t think this is what the author of this myth, Georges Sorel, actually believed. He just thought it was a useful idea for rallying the masses. But lots of folks have always (falsely) believed that if the masses achieved political consciousness and recognized their inherent interests, we’d have super-terrific socialism for as far as the eye can see.

A similar idea lurks, often unspoken, in the idea of massive voter turnout (which is different from universal turnout). It’s the bedrock assumption buttressing Sen. Bernie Sanders’ understanding of politics. Everywhere he goes he sees working class folks—and a lot of hippie grad students—who want what he’s selling, so he assumes that all the Joe Six Packs and grad students who didn’t show up to his town hall agree with him, too. Or at least that they can be convinced to agree with him if properly educated about their class interests.

But this is just a colossal error in logic. For example, let’s stipulate that Star Trek conventions have people from a lot of walks of life—construction workers, accountants, stay-at-home moms, Asians, African Americans, gay people, whatever. The thing is, no one goes to a Star Trek convention and thinks everyone who didn’t show up wants to dress up like a Klingon, too. But in politics people often erroneously treat a big crowd as a representative sample of the much, much bigger crowd that didn’t show up. I will always remember Ted Cruz insisting Americans wanted Obamacare repealed because “everywhere” he spoke, the audiences wanted to repeal Obamacare—as if the people who loved Obamacare were likely to turn out for a Ted Cruz town hall in Abilene.

The truth is that it’s a pretty settled issue among political scientists that if everyone voted, the final results would look pretty similar. Think of it this way: A good poll will ask a representative sample of maybe a couple thousand people. And from that poll, we have a very good picture of what 331 million people think. Well, a presidential election has like 150 million people voting. That’s a huge poll sample. It would be weird if the other 100 million people eligible to vote broke down decisively in favor of one party or another. “Simply put,” political scientists Benjamin Highton and Raymond Wolfinger wrote in 2001, “[American] voters’ preferences differ minimally from those of all citizens; outcomes would not change if everyone voted.” Ten years earlier, Stuart Rothenberg published his study, “What If Nonvoters Voted.” He concluded, “There is no compelling evidence that nonvoters are so distinct from voters that they constitute a bloc ready to alter the fundamental balance of power in this country.”

But here’s where I disagree with that analysis. While mandatory voting wouldn’t yield a socialist nirvana or new MAGA republic, and while it wouldn’t yield particularly shocking results in the short term, over time it would profoundly change the incentive structure for parties and candidates.

The problem with what we might call the Myth of Voter Turnout is that both parties believe it’s true. Democrats are obsessed with goosing turnout because many of their key voters, chiefly African Americans and young people generally, are low-propensity voters, so they rightly assume that getting more of those voters to the polls would help them. But there’s no evidence that high voter turnout always benefits Democrats. Republicans—like Virginia Gov. Glenn Youngkin—often benefit from high turnout. Still, as a general proposition, both Democrats and Republicans think that if more people show up at the polls it will benefit Democrats.

But there’s a big difference between getting more of your voters to the polls and getting all voters to the polls.

A second thing I like about the idea of mandatory voting is that it would take away a lot of the power from people who yammer the most about how the majority of Americans are on their side. Democrats and Republicans operate from the false assumption that they are the sole tribunes of the “American people.” Democrats tend to think they don’t have supermajorities in Congress because hordes of voters, mostly black and brown, are “disenfranchised.” Republicans often talk about how there’s a “silent majority” that needs to be awakened in order to prove that “real America” is with them (which is, ironically, a very Sorelian idea). And, I should point out, the MAGA types have added a conspiratorial bonus claim that any election they lose was “stolen” by the Deep State or George Soros or Something. Trump says he won in a landslide and his useful idiots take it as gospel, guaranteeing they’ll keep losing.

The activists who offer the most extreme version of these various claims love to wrap themselves in the mantle of authentic democracy. Whenever I talk about the problems of primaries and small donors, all of my hate mailers and tweeters tell me how I just want the elites (or the Joooooz) to run everything and that I want to deny “the people” their say in our democracy. Well, what could be more democratic than everybody voting? Again, I don’t like the idea of compulsory voting, but there’s nothing undemocratic about it. All of the problems with forcing people to vote fall under the rubric of “illiberal,” not “undemocratic.”

If everyone voted, the activists who serve as the gatekeepers of the primary system would, over time, lose power. How so? I’m glad you asked. Because of polarization and the stranglehold the bases have on the parties, most politicians are more worried about getting the nomination and not being primaried. Once they have the nomination, they no longer look to win over the median voter the way they traditionally did. Instead, they simply try to gin up turnout from their core constituencies. This logic has infected presidential politics. This was Obama’s strategy in 2008 and 2012, and it was how Donald Trump ran and won in 2016—and how he ran and lost in 2020.

But if everyone voted, getting more of your most committed supporters to the polls would be a waste of resources because they’re going to vote anyway. Instead, the incentive would move back to persuading an actual majority of Americans, not just a supermajority of your most committed voters. Spending all of your time on the minority of voters totally sold on your B.S. would be idiotic, because they’d vote no matter what. You’d need to look outside your most committed voters and persuade people who are turned off by such pandering.

Right now—and I do mean literally right now—both parties are poised to nominate candidates whom most Americans don’t want to vote for. Both are working on the assumption that they’ll be able to win by turning out enough true believers and/or people who hate the other party more. That calculation works only in a system where base turnout is the priority. When 100 percent turnout is guaranteed, the math changes. And eventually, the parties would respond by nominating candidates with broader appeal. Sure, candidates would still try to make voters angry, but their arguments would be more generalized to appeal to broader categories of voters and on less niche issues.

Think of it this way. If you actually believe that everyone who turns up at the Star Trek convention represents the views and aspirations of everyone who doesn’t, you might run for president by promising to follow the Prime Directive. “Let us not question the wisdom of the founders of the Federation!” Or you might run as a candidate who thinks the Prime Directive has outlived its utility. This Wilsonian Trekker would argue that we’ve outgrown such rigid rules. We need a Kirk-like warrior who knows when intervention is in the interests of the Federation and good for the backward aliens we encounter out in the galaxy.

You know what would happen to that candidate out in the real world? They’d be escorted off the debate stage by security, if they were ever allowed on it in the first place. The last thing we’d hear is, “My Vulcan nerve pinch! It does nothing!”

A similar dynamic is at work in many of the bluest and reddest quarters of America. When Kari Lake ran for governor, she held a rally in which she asked if anybody in the room voted for John McCain. “We don’t have any McCain Republicans in here, do we?” Lake asked. “Alright, get the hell out,” she said, before adding, “boy, Arizona has delivered some losers, haven’t they?”

This is like the Trekker candidate saying, “Anybody in here a fan of Benjamin Sisko and Deep Space Nine? All right, get the hell out.”

I still chuckle at Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez’s super PAC vowing to primary Joe Manchin in West Virginia in the hope of finding the “next AOC.” Because you know, West Virginia, where Trump got twice Biden’s share of the vote, is hungry for an AOC clone. Why not just run a candidate dressed like a Romulan?

In short, big chunks of the Republican and Democratic bases are so high on their own farts they think they can defenestrate the impure from their ranks, a belief that is only made possible by thinking that you don’t need them to win because “real America” is already in your column.

The immigration implosion.

Let’s change gears a little bit. The most interesting, and possibly significant, political story right now is the revolt of blue city Democrats over immigration. I really should have led with this and I intended to get here sooner. But what’re you going to do?

I’ll zip through the normal punditry just to set the scene. A bunch of border state Republican governors and Biden’s own Department of Homeland Security, sometimes cooperatively and sometimes not, have sent scads of asylum seekers from the border to big cities. And it’s becoming a massive problem because it turns out that, not counting some rhetorical excess, the Republicans were right. The massive influx of poor migrants was a huge humanitarian crisis that was an unfair drain on the resources of states like Texas and Arizona. I didn’t like the use of these migrants as political props, but sending them north to cities like New York, Chicago, and Washington wasn’t simply a stunt. It was a reasonable response to a crisis being disproportionately borne by a handful of states asked to carry the burden of a national problem requiring a national response. Democrats love to talk about shared burdens, and their bluff was called.

Democrats, particularly Democrats in big urban centers, also loved to talk about how immigration is all upside and anyone who disagrees is a bigot, a nativist, a xenophobe, and just plain mean. That’s why they virtue-signaled their “sanctuary city” policies when such virtue signaling was cheap—both literally and figuratively.

Now, it’s a crisis that could destroy New York City, in the words of Mayor Eric Adams.

While I have compassion for the migrants and for the taxpayers alike, I have zero sympathy for the politicians who preened about their moral superiority to those concerned about uncontrolled immigration.

And that’s what I find interesting and valuable in this crisis. Again, like the Trekkers talking among themselves, a lot of blue-staters talked about immigration as if all decent and reasonable people agreed with them. Now that they see some of the costs of their own stated principles, they’re freaking out. And rightly so.

Part of the reason Democrats could demagogue the issue of immigration is that they saw only upside for themselves electorally. It’s not necessarily true that they all thought they were importing reliable Democratic voters, but the belief that they would end up being reliable Democratic voters made it much easier to demonize people who saw the downside of runaway immigration.

Just to be clear, it was never true that America was anti-immigrant (at least not in the last half-century). As Jim Geraghty notes, “Every year since the millennium, between 703,000 and 1.2 million immigrants have been granted legal permanent residence, also known as getting a green card. Green-card holders are permitted to live and work in the country indefinitely, to join the armed forces, and to apply for U.S. citizenship after five years — three if married to a U.S. citizen.” America has up to 50 million immigrants living here. Add first and second-generation Americans together and we’re talking about between a quarter and a third of the total population.

By the way, I love it when people accuse China hawks of being “xenophobes.” You know what share of (Han-Supremacist) China’s population is composed of immigrants? .1 percent.

As much as I hate the phrase “a crisis is a terrible thing to waste,” the value in this crisis is that it may teach Democrats that cost-free rhetoric isn’t actually cost-free if actually translated into policy. The best thing that could happen for immigration policy is for Democrats to recognize the downsides of immigration. The next best thing would be for Republicans to recognize the upsides of immigration. And while this is definitely a “both sides” point, it’s not symmetrical. Because the American status quo is wildly, unprecedentedly, and almost uniquely pro-immigrant already.

It’s a bit like all of the verbiage about free speech. Right and left seem to trade the baton on who is for or against free speech every couple years, or days, depending on the issue (“Book banners!” “Twitter censors!” etc.), but the crusaders on both sides almost always fail to recognize that whatever the censorial outrage du jour, it’s always against the backdrop of the fact that America is wildly pro-free speech as a matter of culture and law.

Anyway, if both parties could recognize—in the halls of Congress and on dumbass cable shows—that there are significant trade-offs inherent to immigration policy, that would be a huge step toward actually forging an immigration policy, and enforcing it. And making cosseted blue state Democrats recognize this fact where they live could be an important first step toward that.

Just to tie these two topics together, it’s slowly dawning on Democrats that their identity politics-infused assumptions of the electorate are starting to melt in the heat of reality. It’s official: Democrats have a nonwhite voter problem, as Ruy Teixera writes in his essay, “It’s Official: Democrats Have a Nonwhite Voter Problem.” For a long time Democrats have acted like nonwhite voters are axiomatically “the base.” That’s changing. And that’s good.

And that leads me to the thought experiment I wanted to get to but will instead just drop in your lap alongside sentient dolphins and mandatory voting. “What if nonwhite voters voted just like white voters?”

Even baby steps in this direction would shake the Democratic Party to its core. It’s really hard to accuse the opposing party of racism and xenophobia when the opposing party has roughly the same demographic makeup of your party. The more interesting question in some ways is, what would happen to the Republican Party? But I’ll leave that for you guys to discuss.

Various & Sundry

Human and canine update: If you listen to The Remnant you’ll know this already, but the Fair Jessica and I made a momentous decision earlier this year. We bought an RV, specifically a schmancy custom Sprinter conversion van. As you probably recall, we like driving adventures and we really like driving adventures with our dogs. And after my mom passed away, we decided to follow this passion to its logical conclusion. Get busy living and all that. So, on Tuesday, I’m driving out West with Zoë and Pippa to pick up the vehicle. (Please don’t tell them. It’s a surprise.) I’ll meet the missus in Portland (she’ll already be on the West Coast for some work stuff). And we’ll drive the behemoth back home. We’re really excited about it and, yes, you can expect a lot of G-Files and Remnants from the road in the future.

Again, the girls don’t know about the adventure ahead. But I’m sure they will be ecstatic to get out of D.C. where it has been equatorially miserable for the last week. We’ve even waived our—admittedly very hard to enforce—no swimming on weekdays policy. The problem is that creek swimming is a stinky affair. One of our favorite things about hiking out West with the dogs is finding non-swampy, non-polluted water from them to cavort in. Gracie will be fine. We have arranged for a very nice girl to house sit and cat-attend while we’re gone. Gracie, in her old age, has become both more demanding and more lovey-dovey. Anyway, next week you can expect treat videos, day-of-the-week updates, and even hotel room welcoming committee footage.

ICYMI

And now, the weird stuff

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.