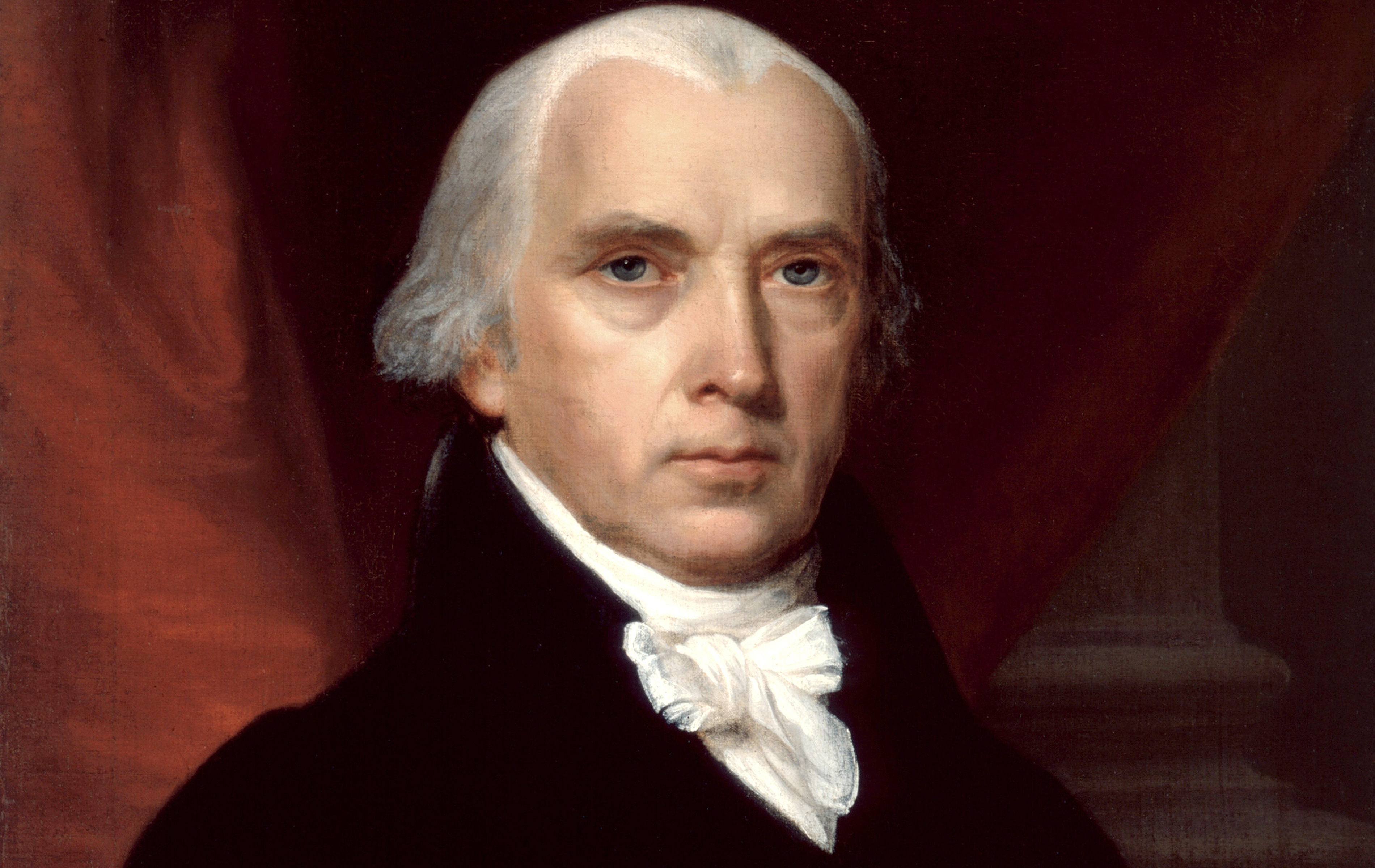

For the past century, the analysis of faction in Federalist 10 has dominated our understanding of the original political theory of the Constitution that James Madison did so much to design. A political theory of the Constitution is different from analyzing how and why it allocates powers to the three departments or divides them between the Union and the states. It instead marks an attempt to identify the interests and passions that will swirl through the body politic. In making faction the topic of his first contribution to The Federalist, Madison also identified it as the “dangerous vice” that must be cured. “The instability, injustice and confusion [it] introduced into the public councils,” he observed, “have in truth been the mortal diseases under which popular governments have every where perished.”

To ask how well Madison’s theory works today, in an era when the Constitution itself seems to be failing, poses a fair but tough question. By common consent, Americans live in an era of tense and bitter polarization. That polarization can be measured in many ways, including the fact that the most conservative Democratic congressman votes to the left of the most liberal Republican—assuming that such creatures even exist. Having the president tell an Iowa rally that he “hates” Democrats “because I really believe they hate our country” marks an abysmal low in presidential rhetoric.

Polarization, as we use the term, means aggressive political partisanship. Yet when Madison and other framers of the Constitution spoke about faction in the late 1780s, they were not—or at least not yet—anticipating the national political parties they would soon be creating. To understand what they meant and whether it still matters requires a bit of historical legwork. So let’s reconstruct how Madison thought about the subject, and why his analysis is still relevant today.

In ordinary usage in 18th-century Britain and America, faction usually meant a group of legislators united around a common leader or devoted to a particular issue. Before the Revolution, the term applied much better to the British House of Commons than it did to American legislatures. Where members of the Commons sat for longer terms and usually heeded aristocratic leaders and patrons, colonial legislators were amateur lawmakers who simply represented the parochial interests of their communities.

The Revolution changed all that. With a prolonged war to wage, the state legislatures had serious business to do, and skilled legislative leaders began to emerge. Questions about taxation, economic regulations, and the public debt were naturally divisive. Political factions were still limited to the legislatures and rarely involved competitive elections. Yet public interest in the real impact of legislation was clearly increasing as ordinary citizens reacted to the economic problems the state governments were facing, and this in turn made the people’s representatives more responsive to the concerns of their constituents.

There were two great sources of inspiration for Madison’s concern with the problem of faction in these early American republics. One was political and derived primarily from his experience as the most influential member of the Virginia House of Delegates in the mid-1780s, where factionalism tinged the legislative process. The other source was intellectual and rhetorical. It had to do with the prevailing political wisdom, which held that republican governments should be small in extent and socially homogeneous. But if in 1787 one wanted to be both a nationalist and a republican, one had to explain why a national republic would be superior to the smaller republics of the individual states. Where the Continental Congress expected the state legislatures to faithfully implement its recommendations and resolutions, Madison believed that the national government had to be fully empowered to enact, execute, and adjudicate its own laws.

Madison began thinking seriously about factionalism as he fashioned his strategy for the Constitutional Convention. He first stated his argument—or better, his hypothesis—in a memorandum he wrote in early April 1787, only weeks before the framers were to gather in Philadelphia. Its working title was Vices of the Political System of the United States. The thoughts he there compiled (a favorite Madison verb) were echoed in speeches he gave at the convention; in a long letter to Jefferson written five weeks after the convention adjourned; and finally in Federalist 10, which was published on November 22, 1787.

Madison started by rejecting the proposition that republics must rely, as ancient and early modern writers had argued, on the civic virtue of their citizens. That might have seemed true amid the “sunshine patriotism” (to crib Thomas Paine’s wording) of 1775 and 1776. But events since then had proved that belief was naïve. Americans were like other people. They acted out of self-interest and other similar motives, and when they could join popular majorities that would pursue their preferences, they would not hesitate to do so.

The classic statement of this position came in Federalist 10, and it had three major elements.

The first was a matter of definition: “By a faction I understand a number of citizens, whether amounting to a majority or minority of the whole, who are united and actuated by some common impulse of passion, or of interest, adverse to the rights of other citizens, or to the permanent and aggregate interests of the community.” In a republic, a faction was more about citizens than legislators; and it could be a majority as easily as a minority, which seems surprising in a government predicated on majority rule. A faction, therefore, is defined not by numbers, but by the nature of its political commitments, and whether they are consistent with the collective public good of society.

The third element—and I am deliberately going out of sequence here—is the one that scholars have consistently emphasized ever since the progressive historian Charles A. Beard gave Federalist 10 a prominent place in his influential 1913 book, An Economic Interpretation of the Constitution of the United States. Madison closed the famous paragraph in which he listed the multiple sources of faction by observing that “the most common and durable source of faction, has been the various and unequal distribution of property.” For Beard, this passage meant that the real political animus behind the Constitution had been the desire of the propertied creditor class to establish a national government with the resources needed to repay the public debt left over from the Revolutionary War.

While the Beard “thesis” still echoes today, the dominant modern interpretation of Federalist 10 understands that Madison was mainly concerned with redeeming the cause of republicanism against its critics. True, Madison did worry deeply about the danger of paper money laws that would favor debtors at the expense of creditors. But his concern with the problem of faction was hardly limited to economic matters alone.

That is what makes the second element of his critique in Federalist 10—deliberately passed over earlier—so intriguing. His opening list of the “latent causes of faction” still seems germane to our current hyper-polarized polity:

A zeal for different opinions concerning religion, concerning government, and many other points, as well of speculation as of practice; an attachment to different leaders ambitiously contending for pre-eminence and power; or to persons of other descriptions whose fortunes have been interesting to the human passions, have in turn divided mankind into parties, inflamed them with mutual animosity, and rendered them much more disposed to vex and oppress each other, than to co-operate for their common good.

In these examples, Madison was talking, in effect, about the role of passion in politics. To the 18th-century mind, passion and reason were contending forces in political life. Economic interests involved matters one could rationally calculate. But the factors that inflamed political passions were far more difficult to control, and thus would prove far more conducive to a politics of polarization.

Madison’s famous answer to this dilemma involved asking how the effects of factions could best be contained or “cured.” He did not have to produce a perfect model; all he had to demonstrate was that in “the extended republic of the United States,” the national government would always resist faction better than the states because it would embrace a greater diversity or “multiplicity” of interests. The people would still feel the same passions, some of which would be unjust. But the difficulty of coordinating them in durable coalitions would prove far greater.

There were, however, two fundamental problems with this analysis, one that Madison recognized at the time, and another that would depend on the evolution of presidential politics.

Madison knew from the outset that there was one great exception to his theory. One dominant interest could divide the Union on a regional basis: chattel slavery of African Americans. Its presence or absence could define the social and political character of entire regions, and in adversarial ways. As Madison told his fellow delegates on June 30, 1787, this was the true source of division among the states, not the specious contrast between large and small states.

The second problem, which could not have been anticipated in 1787, was the impact of the presidential election system on national politics. Because the Constitution vests the entire “executive power” in a single person, it creates a powerful incentive to form two nationally competitive parties—unlike a parliamentary system, where the control of the executive would depend on forming coalitions within the legislature.

The Framers wanted to have an executive that was politically independent of the legislature, and because control of the executive was so important to the control of the government, that made it more important to create interregional coalitions—thereby, they thought, reducing the chance of regional division. As a result, in 1787 most of the Framers doubted that a popular election of the president would produce decisive majorities—that is, an electorate capable of choosing between two obvious frontrunners. But that is exactly what happened in our first contested election of 1796, when then-Vice President John Adams and former Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson were national rivals for the presidency.

For the first six decades of government under the Constitution, party leaders worked hard to minimize the impact of slavery on national politics. The issue was inherently and potentially bitterly divisive, and down to his death in 1836, Madison remained acutely aware of the threat it posed to his entire constitutional project. But that understanding broke down in the 1850s. With the formation of a militant Republican party, antislavery sentiment became impossible to suppress politically. And when Abraham Lincoln captured the presidency with all his electoral votes coming from free Northern states, the South decided—quite wrongly—that secession was its better option. Here was the regional division that the founders had feared, and in its worst possible form.

To make a leap from this era to our highly polarized political system today would obviously require far more space than is available here. But even now, as a working historian trying to imagine how my later counterparts will write this story, I believe there are at least four critical factors that they will need to take some time explaining.

First, the working character of the House of Representatives was radically transformed by the short-lived speakership of Newt Gingrich in the mid-1990s and the emergence of the Tea Party caucus after the great housing and financial crisis of 2008. The existing political culture of the House was destroyed, to be replaced by far more rancorous habits which encourage both parties not only to criticize but to actively mock each other’s behavior.

Second, the great concern of Republican incumbents in both houses of Congress is the fear of being primaried. Party primaries are dominated by the most ideologically driven voters. Democrats remain pretty much the party they have always been, but intraparty politics have been pushing the Republicans ever further to the right.

Third, while one might have naïvely hoped that the election of Barack Obama would have introduced a new era of post-racial politics, race remains a potent source of political antagonism. This is especially the case in the South. It was true in 1861, when most of the slavery states seceded simply because the Republicans captured the presidency; during the era of Jim Crow segregation, when African Americans basically lost suffrage; and during the period of massive resistance that followed the Supreme Court’s 1954 decision in Brown v. Board of Education. And it seems to be true again today, when a very different Supreme Court seems likely to nullify the Voting Rights Act of 1965, even though Congress has repeatedly amended and strengthened it in 1970, 1975, 1982, 1992, and 2006.

Fourth and finally, no figure in American politics has (to borrow Madison’s language in Federalist 10) more fully performed the role of “ambitiously contending for pre-eminence and power” in the way that our twice-impeached, coup-fomenting 45th and 47th president has. Presidential historians in the style of Doris Kearns Goodwin and Michael Beschloss have been fond of comparing the behavior of different presidents in the hope of drawing useful lessons for the present. But Donald Trump is a uniquely divisive figure who bears no comparison to any other figure in American presidential history (though perhaps Andrew Johnson could be a distant contender).

Speaking (as I often do) within a Madisonian framework, Trump’s entire political career illustrates that demagoguery, despite the founders’ attempts to defend against it, remains an active and even dominant force in modern American politics, with consequences as yet unforeseen but all too easy to imagine. With his attack on many of the underlying norms of democratic governance, and his vociferous attacks on all his critics and opponents, we risk shattering the norms of governance that are essential to democratic government.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.