One of the enduring European criticisms of America is that we are too prudish, too moralistic, and too idealistic. Unlike our weltschmerz-besotted betters across the pond with their turgidly tragic theater and cynical cinema, we make everything into a huggermuggering moral folderol.

I’ll return to that in a moment, but first let’s talk about József Szájer, a Hungarian member of the European Parliament in Belgium.

Szájer is a founding member of Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán’s Fidesz Party. Among Fidesz’s many controversial priorities is an ongoing crackdown on homosexuality. Presumably inspired by Vladimir Putin, who has incorporated distaste for homosexuality into a broader nationalist moral panic, Orbán’s Fidesz sees homosexuality as a kind of treason against the national soul. This sort of thing is very popular among authoritarian types, particularly when they don’t have enough Jews or immigrants to demonize (though that hasn’t stopped Orbán from playing those games as well). Szájer himself has reportedly boasted about how he personally rewrote the new Hungarian Constitution to define marriage as a heterosexual institution.

Now, I fully understand the arguments that marriage is a heterosexual institution, and I think reasonable people can have that debate while nonetheless acknowledging that, as a practical matter, that ship has sailed in the United States. Regardless, that’s not why I bring him up.

This week, Szájer was arrested fleeing a party held in contravention of Belgium’s coronavirus rules. According to press accounts, the party was in fact a gay orgy—presumably in both the antiquated and modern usages of the adjective. At least, one hopes that’s the case, given that unhappy orgies sound like particularly bleak affairs. Note: The Belgian police broke up the party not because it was an orgy, gay or otherwise, but because it was an unsafe mass gathering during a pandemic. Of course, social distancing would defeat the point of the get-together in the first place, in the same way that staying six feet apart would make a Greco-Roman wrestling match a rather anemic exercise.

I can only presume that face masks were not worn either. At least not of the medical variety.

But again, that wasn’t the point.

Szájer is married to a well-known—and by all accounts, female—Hungarian lawyer and judge. They have a daughter.

And to his credit, he did apologize to his family. But, first, he apologized for his real offense:

“I deeply regret violating the COVID restrictions—it was irresponsible on my part. I am ready to pay the fine that occurs.”

So why do I bring this up? Well, firstly because it would take a heart of stone not to laugh.

Second: Compared to the drumbeat of stories about hypocritical—mostly very liberal—public officials heaping shame on citizens for defying pandemic rules they then promptly break, this is just the bee’s knees. I mean, having dinner with a bunch of people at the French Laundry or getting on a plane to visit your family while telling people not to do anything of the sort is one thing. But trying to cleanse Mother Hungary of the scourge of Dorothy’s Friends while hitching your freak flag to the banner of “What happens in Brussels stays in Brussels,” and then offering a heartfelt apology for … violating a civil ordinance against meeting in large groups? This is a pas de deux of “do as I say, not as I—or whom I—do.”

I’ll take American hypocrisy any day.

The trouble with American Puritanism.

Like all enduring clichés there’s some truth to the European critique of America as too fastidiously principled and moralistic. H.L. Mencken absorbed a bit too much Nietzschean nihilism to be quintessentially American, but just enough to offer brilliant—or at least entertaining—observations about the American quintessence. And central to his barbs against America was his self-appointed role as America’s Ahab against the white whale—and wail—of Puritanism.

“That deep-seated and uncorrupted Puritanism,” he wrote, “that conviction of the pervasiveness of sin, of the supreme importance of moral correctness, of the need of savage and inquisitorial laws, has been a dominating force in American life since the very beginning. There has never been any question before the nation, whether political or economic, religious or military, diplomatic or sociological, which did not resolve itself, soon or late, into a purely moral question.”

I think there’s much truth here, but it misses that what Americans tend to moralize about are what they see as fundamental issues of rights.

My friend Charlie Cooke likes this facet of the American character (and so do I, though not as much as he does). The willingness to turn minor questions into grand philosophical debates, and having the tendency to panic about slippery slopes, turns out to be one of the only things that adds some countervailing friction to those slopes to stop them from actually getting, well, slippery. A country that is willing to make a profound fuss about some tiny infraction against one’s liberties is less likely to countenance a wholesale assault on those liberties. A society that gets into a grand debate about whether it should be legal to own hundreds of guns will be less inclined to ban the ownership of any guns.

William F. Buckley, in an argument with Murray Rothbard, once observed that, “If our society seriously wondered whether or not to denationalize the lighthouses, it would not wonder at all whether to nationalize the medical profession.” (The issue of private lighthouses is actually a contentious affair beyond the scope of this “news”letter).

There is a compelling logic to this sort of argument. The problem is that when you look at the facts on the ground, it gets a bit more complicated. Yes, Mencken was right that our arguments are often really about morality even though we frame it in the language of rights, but underneath the mask of morality is the desire for power.

The best example of this is the realm of free speech. Fun fact: The Berkeley Free Speech movement was never really about free speech, it was about a movement draping itself in the flag of free speech while trying to maximize its political power.

The new puritanical censors of the left and the right alike invoke the language of rights to argue about power. Various progressives want to curtail speech they don’t like because they don’t like it. So they invent claims about the “right” not to be “triggered” or to have their feelings hurt. “I don’t want to debate. I want to talk about my pain,” explained one Yale student.

On the right, the hullabaloo about “Internet censorship” and Section 230 isn’t really about free speech, it’s about power. As a free speech issue, the matter is pretty straightforward: Private companies can say—or allow to be said—nearly any damn thing they want on their platforms. This makes popular platforms very powerful, and some people don’t like that and want to exert power over them. Yes, there are legitimate issues at the margins, but for the most part the political energy behind all this argy-bargy is that a bunch of people think the president and his most passionate supporters should be able to say anything they want, including lies, on privately owned platforms without any editorial comment or discretion getting in the way. That’s an argument about power, plain and simple.

One cheer for hypocrisy.

Nobody likes admitting—to themselves least of all—that they’re fighting for political power. We like to make everything about principle, particularly in America. This is one reason why we obsess so much over hypocrisy in this culture. Hypocrisy is bad, but it’s not nearly as bad as political combatants make it out to be. Let’s suppose I am a heroin addict who goes around telling people not to use drugs. Yes, I am a hypocrite. But I wouldn’t be a better person if I went around trying to convince everybody to chase the dragon. If I said, “Come on, kids, do it. It’ll make you cool,” I’d be less hypocritical, but a worse person.

The value of hypocrisy in the political realm is that it helps us identify when the mask slips and we get to see the baser motivations behind supposedly noble motives.

Whatever your preferred framing—the culture war, political polarization, or the supposedly apocalyptic struggle between the forces of socialism and nationalism—what we’re really seeing is a decidedly Puritan moral battle between competing sets of Puritans. Some—many—of them are sincere in their moral beliefs, but even when they are sincere, the conviction that they are right to hate and fear the other set of Puritans gives them permission to bend or ignore their own principles and overlook their own side’s manifest hypocrisies. Right now, we have supposed superpatriotic lovers of American liberty calling for our lame duck president to declare martial law to hold onto power. It’s necessary, you see, because the president believes so passionately in our sacred principles like constitutional fidelity and marital fidelity. If you find yourself calling for martial law—or the execution of public officials—because you think that only Donald Trump can fight for the Constitution and family values, you might want to sit out a few plays. Heck, I think you should call over the waterboy or the medic with the oxygen tank if you think he was ever really fighting for that stuff at all.

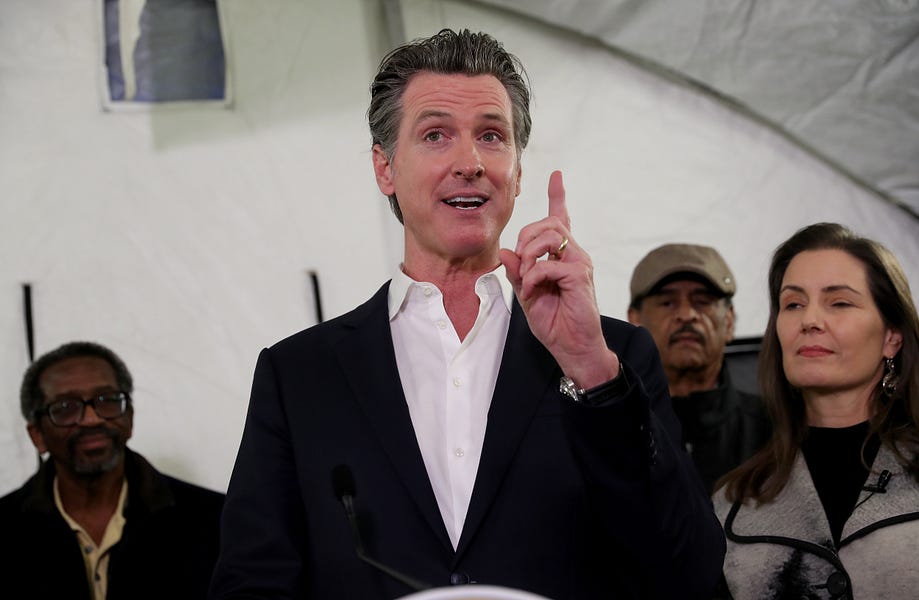

I find this hypocrisy more galling than the hypocrisy of Gavin Newsom & Co. for the simple reason that it is more galling. But I look forward to the day when I can concentrate more rage leftward—at the hypocrites who prattle about helping the poor while championing bailouts for middle- and upper-class grad students, at the private equity moguls and cosseted meritocrats of the new petite bourgeois who check their stock portfolios while riding out the pandemic in the Hamptons and tweeting about socialism; at media scolds who mock the Trump suck-uppery of right-wing media while wallowing in a Belgian orgy-like frenzy of sycophancy for Democratic politicians; and, yes, at the politicians and public health experts who think the Black Lives Matter sigil is like an anti-malarial mosquito net for COVID-19.

But I will confess that the last four years have pushed me Mencken-ward. I can’t unsee that there are plenty of hypocritical power-maximizing Puritans on both sides. To paraphrase Mencken, the problem with Puritans is not that they try to make us think as they do, but that they try to make us do what they think we should do.

Or, as József Szájer might say, gay orgies for me, traditional marriages and pandemic lockdowns for thee.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.