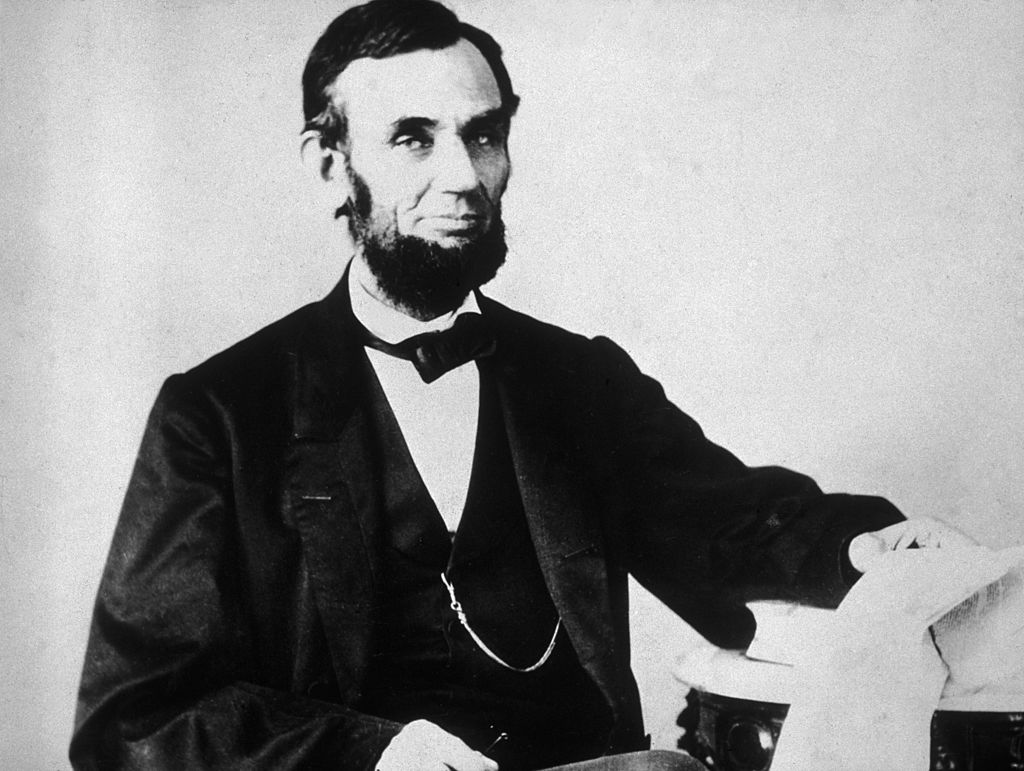

The subject of a third major political party in the United States brings out generally predictable reactions: cynicism in cynics, fantasy in fantasists, partisanship in partisans. But it is worth remembering that there already has been a very successful third party: the Republican Party, which skyrocketed to power very shortly after its founding in 1854, with the first Republican president, Abraham Lincoln, winning the White House in 1860. By contrast, the Libertarian Party, founded in 1971, has topped out at 3.3 percent in presidential elections—and that was in 2016, when the party’s ticket comprised two moderate Republican former governors (Gary Johnson and William Weld) running against two corrupt and contemptible New York Democrats, Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump. The Libertarians have not had much success in state legislatures or town councils or school boards. The Greens and the other exotic minor parties are for hobbyists, the political equivalents of people who build miniature ships in bottles or collect stamps.

The Republican Party emerged from the wreckage of the Whig Party because the Republicans believed in something and the Whigs did not: When it came to the most important issue of the day—slavery—the Republicans had a firm position, if a painfully moderate one, while the Whigs could not quite figure out what they should think about it. The Republicans were not a radical abolitionist party but a conservative anti-slavery party that ended up being the political home of radical abolitionists because the abolitionists had nowhere else to go. Lincoln’s position on slavery was, in fact, much narrower than many of those of us who admire him might have wanted from him at the time: He did not propose to abolish slavery but only to prevent its spread in the hopes that it would die out on its own; a constitutionalist might concur with Lincoln’s assertion in his first inaugural address that as president he did not have the power to interfere with slavery in the southern states, but Frederick Douglass was not wrong to fault him for going beyond that to add that he would not be inclined to use such power if he had it. The word politician has a disreputable odor on it, but Lincoln was a gifted and wily politician, a politician of the first order, and it was such a politician that the convulsing republic needed. A saint would have simply denounced slavery as an unbearable moral evil—which, of course, it was—but it took a politician to work against that evil while also working to ensure that the United States would remain the United States, enduring even through the treachery of the slave power and the brutality of the Civil War. It was Lincoln’s saintliness that failed him and us, setting the course toward a Reconstruction that was too conciliatory and insufficiently reformist.

A compromise position is not necessarily a position that lacks moral clarity—it may be, and often is, a position that recognizes the limitations of the current political situation and that does not indulge the adolescent tendency to pine for the impossible. At the same time, a position that is uncompromising or even extreme often is one that lacks genuine clarity, moral or political.

The Republican Party in our time is a confused and debased thing. Trump and Trumpism have made that worse, but the decadence of the GOP did not begin in 2016. Faced with the great moral question of their day, the Republicans of Lincoln’s time offered moral firmness tempered by realism; faced with the great moral questions of our time—abortion, Russia, the attempted coup d’etat of 2021—Republicans offer moral hysteria instead of moral firmness, delusion rather than realism. (It does not help that on two out of three of those big issues, a great many Republicans are on the wrong side.) But even on abortion, Republicans are now unsteady. In the pre-Dobbs era, Republicans could organize themselves around the outrage that was Roe vs. Wade, as naked a piece of judicial usurpation of the lawmaking power as modern American history has to offer. But with Roe vacated, Republicans have been made to give up the thing they are good at—opposition—and instead try to do the one thing that they have shown themselves more or less incapable of for 30 years or more—governing.

There are edge cases in abortion as in anything else, hard calls and ethically complex situations, and these should be approached carefully and compassionately. But such complexity is not a factor in the great majority of cases when it comes to abortion, which in the United States is mostly a savage and purely elective form of birth control. But let us proceed, arguendo, as though there were no complex moral coloration at issue in abortion—that would not necessarily render the issue more tractable as a political question. The immorality and viciousness of slavery was perfectly clear—even to many owners of slaves, such as Thomas Jefferson—but that did not make it easy or straightforward to handle as a matter of politics.

It is possible (likely, I think) that the current backlash against anti-abortion policies is exaggerated or that it will prove transient. But it is a real phenomenon, one that cannot simply be ignored as a matter of political practice.

We live in a time in which politics is both tribal and sacralized: Having abandoned the old faith and the old creeds, Americans (and not only Americans) have sought out new sources of meaning and identity, and the majority of us have settled—in a moment of catastrophic national stupidity—on politics as the substitute for religion, family, and community. (You can read about why and how this happened, and what it means, in The Smallest Minority.) It is that cultural tendency and not some newfound ideological inflexibility that makes bipartisanship, compromise, and consensus effectively impossible in our time: If those on the other side of the aisle are not merely Americans who disagree but our enemies, then cooperating with them in any way represents (so this line of thinking goes) a kind of moral contagion. That is why both Republicans reject, even in the form of hypotheticals, compromises in which they get 90 percent of what they want in exchange for giving the Democrats 10 percent of what they want—and why Democrats do the same thing.

Naïve partisans, be they Republicans or Democrats, always tell themselves the same things: The other side fights dirty, and we’d get our way if only we fought dirty, too; the other side is uncompromising, and we’d get our way if only we were equally uncompromising; the people are really on our side, and the other side only wins because the people are misled by nefarious and powerful forces behind the scenes; if only we would really fight, then we could do whatever we wanted, and not have to work with the other side. All of that is delusional, but it is what people think—and it is about 90 percent of what they hear on talk radio, Fox News, MSNBC, etc.

Ironically, Republicans are now at their least compromising on abortion at precisely the moment when the Republican Party’s rank-and-file foot-soldiers are less committed to the anti-abortion cause than they have been in a generation, their numbers having been swelled by social-media populists, most of them with no particular religious attachment and having undergone no particular moral formation, who admire Donald Trump because of his hedonistic porn-star shenanigans, not in spite of them. These Republicans are socially and culturally much more like their Democratic opposites than they would care to admit, and their politics is a politics of grievance-airing and status-seeking.

There are some Republicans who are pretty good at articulating what they’d do about abortion nationally if they had uncontested power, or if they had at the national level the kind of wide political latitude that Republicans enjoy in Texas, Florida, or Oklahoma. Explaining what they will do in a context in which Democrats get a vote, too—and in which Democrats slightly outnumber Republicans—they are not so good at. Partly this is because it is distasteful to engage in moral compromise on a life-and-death issue such as abortion, but in larger part this is because the idea of compromise with Democrats about anything is agonizing to them. It is not what they have organized their party and their individual careers to do.

The ongoing abortion fight will create some real challenges for Republicans, beginning with Ron DeSantis. One year ago, the Florida governor signed a law severely restricting abortion after 15 weeks of pregnancy; now, the Florida legislature is poised to send him a bill that would narrow the abortion window to six weeks. The 12-to-15-week window is much closer to where Americans are on the issue, and it is closer to the norms in Western Europe—as a political matter, it is easier for Republicans to be able to point to abortion regulations that they can defensibly characterize as being no more radical than those of France. In a perfect world, there would be no abortion at all, but we live in this imperfect one, in which policy proposals that cannot be realized in the political environment that actually exists are not, properly speaking, political proposals at all, but are better characterized as philosophical exercises.

Anti-abortion advocates who want to expand the range of the politically possible have a big job in front of us, one that does not begin with electing anti-abortion politicians (we have plenty of those) but with persuasion and consensus-building. Big, durable social changes require consensus—as the anti-abortion world knows at least as well as anybody else, even a brute-force imposition of policy by the Supreme Court, as in Roe, will eventually fail without genuine widespread social and political buy-in. That buy-in doesn’t have to be universal—I am writing for adults here—but it does have to be wide and deep.

The Trump-era Republican Party talks a great deal about “winning,” but it often behaves like a party that does not want to win—which is to say, if it were a party that did not want to win, it would behave in much the way it does. It is an angry party for angry people, it demands new and invigorating things to be angry about, and taking a source of anger off of the table by winning—even if it is a limited compromise win—would be a kind of psychic net loss for today’s Republicans.

How is that working out? The Republicans lost in 2018, in 2020, and in 2022. And 2023 has seen the victory of the leftwardmost candidate in the Chicago mayor’s race along with the loss of conservative control of the state Supreme Court in Wisconsin—in an election that was fought largely on abortion. Republicans are currently rallying behind a proven election loser who is laboring under the weight of felony indictments related to his dalliances with porn stars and Playboy models, and who is likely to soon be carrying the weight of more indictments related to his dalliances with coup-plotters and every species of crackpot found in the vast Chalmun’s Spaceport Cantina of the American Right.

The Whigs couldn’t figure out what to do about the great issue of their time. The Whigs also were home to a great deal of anti-immigrant and nativist sentiment associated with what would become known as the Know-Nothing movement and the short-lived American Party, which ran ex-Whig Millard Fillmore for president in 1856. Whig bigwig William Seward, who would go on to serve in the Lincoln administration, put it thus: “Let, then, the Whig party pass. It committed a grievous fault, and grievously hath it answered it.”

Republicans who don’t believe in third parties should pause to reflect that they are in one.

Economics for English Majors

Writing in the New York Times (“Putin’s Energy Offensive Has Failed”) Paul Krugman makes a series of sensible observations climaxing in a conclusion that is, if not quite preposterous, then at least non-obvious.

Professor Krugman argues that Vladimir Putin has launched four main offensives: three of them military assaults on Ukraine and one of them an energy assault on the European Union and other allies and supporters of Ukraine, hoping to weaken the ability—and willingness—of European nations to provide ongoing material support for Ukrainians’ heroic efforts to resist the Russian invasion of their country.

[T]he big story — a story that hasn’t received much play in the news media, because it’s hard to report on things that didn’t happen — is that Europe has weathered the loss of Russian supplies remarkably well. Euro area unemployment hasn’t gone up at all; inflation did surge, but European governments have managed, through a combination of price controls and financial aid, to limit (but not eliminate) the amount of personal hardship created by high gas prices.

And Europe has managed to keep functioning despite the cutoff of most Russian gas. Partly this reflects a turn to other sources of gas, including liquefied natural gas shipped from the United States; partly it reflects conservation efforts that have reduced demand. Some of it reflects a temporary return to coal-fired electricity generation; much of it reflects the fact that Europe already gets a large share of its energy from renewables.

Price controls are not words that warm the libertarian heart. As Krugman notes, there is a notional worldwide market for natural gas, but, in practice, the gas trade is highly localized, because the most efficient way to transport it is via pipeline. If those pipelines bringing gas in from Russia go offline, the Germans and the Poles can’t just magic new gas and new pipelines into existence. What the Europeans have adopted is what they euphemistically call a “market correction mechanism”—Krugman’s “price controls” is more direct—that limits how far European gas prices can diverge from world market prices. The mechanism relies on one-month, three-month, and one-year derivative contracts to benchmark gas prices for “market correction.” The European Council describes the program thus: “The regulation is a temporary emergency measure which aims to limit excessively high gas prices that do not reflect world market prices, while ensuring security of energy supply and the stability of financial markets.” Along with price controls, the libertarian heart skips a beat at the words temporary emergency measure, which have a way of being non-temporary and far outliving the emergency.

But, as Krugman observes, the results have been pretty good. The EU economy has not been crushed by Moscow’s energy weapon. Krugman again:

Democracies are showing, as they have many times in the past, that they are much tougher, much harder to intimidate, than they look.

Finally, modern economies are far more flexible, far more able to cope with change, than some vested interests would have us believe.

I’ll spare you my full lecture on this for the moment, but keep this in mind: It is a myth, and a libel, that free and open societies are weak, and especially that they are weak in comparison to autocracies such as Vladimir Putin’s Russia. Free and open societies end up being strong and rich because they are free and open—not the other way around—and they are resilient (even antifragile) because they have lots of redundancy and duplication of effort rather than highly vulnerable single points of failure, while their institutions (economic and other) are refined and tested by competition. There is a lot of nonsense and tomfoolery that goes on at Harvard and Princeton, Google and Apple, the Pentagon and NASA, etc., but they remain the best in the world at what they do in no small part because these institutions exist in a society in which the competition for resources is constant and dynamic. That is true in the European Union, too. We get a lot of man-on-horseback posturing (sometimes literal) from the likes of Putin, while the archetypal European leader is a bland bureaucrat such as Ursula von der Leyen. I am at least 83 percent sure that Vladimir Putin would have bested Angela Merkel in an arm-wrestling contest even at Mutti’s prime, and I won’t argue with you if you say that Olaf Scholz reminds you of a guy who might be managing a hotel in Winklmoosalm-Steinplatte if he weren’t the German chancellor, but it has been 30 years since Germany and Russia were anything like evenly matched powers, and it is all the boring stuff that has made Germany powerful: trade, property rights, rule of law, democracy, reasonably effective public administration, alliances, etc. The people who want to tell you that liberal democracy is yesterday’s news and that the future is Viktor Orbán’s Hungary are full of it.

Where I depart from Krugman is here:

For as long as I can remember, fossil-fuel lobbyists and their political supporters have insisted that any attempt to reduce greenhouse gas emissions would be disastrous for jobs and economic growth. But what we’re seeing now is Europe making an energy transition under the worst possible circumstances — sudden, unexpected and drastic — and handling it pretty well. This suggests that a gradual, planned green energy transition would be far easier than pessimists imagine.

As Professor Krugman himself notes earlier in the column, what has filled in the gaps in the European energy supply is hydrocarbons—liquified natural gas from the United States and elsewhere, as well as that great staple of the 19th century, coal. That is how you end up with Germany cutting its energy consumption by almost 5 percent while its greenhouse-gas emissions remain unchanged. Renewables are great—it is good to have access to lots of different fuels and power sources, and it is better still if they come with environmental benefits—but if you really want to eliminate greenhouse-gas emissions from electricity production, the only real viable solution that is technologically and economically viable right now is nuclear power. And Germany’s struggles would have been even less painful than they were if the Germans hadn’t sidelined so much nuclear power—a mistake that the French and others have managed to avoid. Instead, the Germans had to arrange emergency hydrocarbon imports and fire up coal plants. What the failure of Putin’s energy war really demonstrates is that you want to have lots of choices—and lots of trading partners—when it comes to energy, and that taking nuclear power offline for no good reason leaves you more vulnerable to energy shocks than you have to be.

Words About Words

First: Plebeian, not plebian.

Next: A New York Times headline: “I Lied To My Father Who Had Dementia.” Unless this is one of those modern two-dads things, you want a comma in there. “Paul Simon, who used to perform with Art Garfunkel, has the same name as a former senator.” vs. “The Paul Simon I’m calling for is the Paul Simon who used to perform with Art Garfunkel.”

And more: I have been corresponding with my friend Jay Nordlinger about underway and under way. The two often are used interchangeably now, but I think there is a distinction there worth preserving.

If you have been to Rome or New Delhi, or many cities with surface trains, as in the Philadelphia suburbs, then you have encountered a pedestrian underpass, usually stairs to a little tunnel that goes under a busy street or a train track. This is an underway, a sort of reverse overpass.

(And you can appreciate around Passover why you’d want to preserve overpass. Different words for different things!)

Jay notes of a former National Review editor and underway: “The late Julie Crane used to insist on this.” So did the Associated Press Style Book, once upon a time. So did most dictionaries, though the distinction mostly is lost.

Under way was originally a nautical term, describing a ship that had begun its journey. This marine usage found in English back to the 17th century, while the more modern sense, referring to any work in progress, is seen only from the 20th century. Why under way and not on the way? One possible explanation is that the English was influenced by the Dutch version, onterweg, which predates the English by some time.

Well, If You Put It That Way …

Elsewhere

A Czech man faces criminal charges for wearing forbidden symbols at an anti-government protest. If you need a reminder of why we need the First Amendment, here is one. More in the New York Post.

You can buy my most recent book, Big White Ghetto, here.

You can buy my other books here. It is royalty-check season, which reminds me that it is time to finish up another book.

You can see my New York Post columns here.

Has the environmental movement ever struck you as being kinda-sorta religious in its orientation? Check out my CEI monograph Inside the Carbon Cult.

In Closing

Happy new year, my friends.

There are all sorts of new years—liturgical, the one in January, the beginning of the school year (which has always seemed to me like the real new year), each offering its own promise of renewal, a new life or a new kind of life. There are other life events that offer similar promise: moving to a new city, taking a new job, getting married. That’s all mildly delusional, of course—it is rarely that anybody ever really changes—but that hope is part of being human. It is very close to the center of being human. C.S. Lewis argued that it is the longing for a different life that points us toward the truth that there is another life, a different one—real life. Lewis writes:

In speaking of this desire for our own far off country, which we find in ourselves even now, I feel a certain shyness. I am almost committing an indecency. I am trying to rip open the inconsolable secret in each one of you—the secret which hurts so much that you take your revenge on it by calling it names like Nostalgia and Romanticism and Adolescence; the secret also which pierces with such sweetness that when, in very intimate conversation, the mention of it becomes imminent, we grow awkward and affect to laugh at ourselves; the secret we cannot hide and cannot tell, though we desire to do both. We cannot tell it because it is a desire for something that has never actually appeared in our experience. We cannot hide it because our experience is constantly suggesting it, and we betray ourselves like lovers at the mention of a name. Our commonest expedient is to call it beauty and behave as if that had settled the matter. Wordsworth’s expedient was to identify it with certain moments in his own past. But all this is a cheat. If Wordsworth had gone back to those moments in the past, he would not have found the thing itself, but only the reminder of it; what he remembered would turn out to be itself a remembering. The books or the music in which we thought the beauty was located will betray us if we trust to them; it was not in them, it only came through them, and what came through them was longing. These things—the beauty, the memory of our own past—are good images of what we really desire; but if they are mistaken for the thing itself they turn into dumb idols, breaking the hearts of their worshipers. For they are not the thing itself; they are only the scent of a flower we have not found, the echo of a tune we have not heard, news from a country we have never yet visited.

And there is news from that unknown country—good news, indeed.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.