When is a presidential field too big?

We could propose objective benchmarks to answer that question but it’s more of an I-know-it-when-I-see-it thing to me. When a longshot as thoroughly hopeless as Doug Burgum is taking up space on the national debate stage, for instance, the field is officially Too Big.

As more candidates entered the race this summer, comparisons to 2016 became irresistible. That was another cycle in which the field was too big, and its bigness brought the Republican Party to ruin. The larger it got, the more fractured the anti-Trump bloc became; as it did, the task of solving the collective-action problem grew unmanageably difficult. In the end, a diehard populist plurality easily conquered the divided conservative resistance.

With Mike Pence, Chris Christie, Will Hurd, and, yes, Doug Burgum each having piled out of the clown car since the start of June, the ominous sense that this campaign can end only one way—we know it because we’ve seen it—is inescapable.

Mitt Romney shares our anxiety.

On Monday the Wall Street Journal published his op-ed calling on the megabucks donors who are propping up no-hopers to pull the plug sooner rather than later this time. It’s good advice, irrefutable even. There’s no scenario I can think of in which a large field that persists into next year would hurt Trump more than it would help him. Over the course of more than 12 months, he’s never polled lower than 43 percent in the RealClearPolitics national average. If there’s any prayer of uniting the other 57 against him, limiting the number of options is the first necessary step.

Join or die. Learn from history.

What’s strange about Romney’s piece, though, is that it ends up reminding the reader inadvertently that 2024 isn’t much like 2016 in the ways that matter.

The strategic medicine he’s prescribing is effective and may well have cured the patient if taken during Trump’s first run for president. Eight years later, with the disease having spread through the Republican body politic, I fear Dr. Mitt’s Rx is more a matter of trying to slow the progress of an illness that’s already terminal.

Start with the fact that his treatment plan begins way too late during primary season to do any good. Romney writes:

Despite Donald Trump’s apparent inevitability, a baker’s dozen Republicans are hoping to become the party’s 2024 nominee for president. That is possible for any of them if the field narrows to a two-person race before Mr. Trump has the nomination sewn up. For that to happen, Republican megadonors and influencers—large and small—are going to have to do something they didn’t do in 2016: get candidates they support to agree to withdraw if and when their paths to the nomination are effectively closed. That decision day should be no later than, say, Feb. 26, the Monday following the contests in Iowa, New Hampshire, Nevada and South Carolina.

…

Our party and our country need a nominee with character, driven by something greater than revenge and ego, preferably from the next generation. Family, friends and campaign donors are the only people who can get a lost-cause candidate to exit the race. After Feb. 26, they should start doing just that.

February 26? After the first four early states?

That’s like holding off on chemotherapy for a Stage 3 cancer patient until they’re deep into Stage 4 and ready for life support.

In 2016 Trump won three of the first four contests, losing only Iowa to Ted Cruz. Less than two weeks after his victory in Nevada, the last of the early four states, he bounced out to his highest number in national polling to that point of the campaign. Some two weeks after that, following another series of wins on Super Tuesday, he soared to 43 percent among Republicans and never looked back.

Momentum matters. And it’ll matter in 2024 more than it did in 2016.

Ron DeSantis and Tim Scott have invested heavily in Iowa this cycle, believing a win there will propel them into the sort of national two-man race with Trump that Romney envisions. Chris Christie is following the same strategy in New Hampshire. Nikki Haley may be counting on her home state of South Carolina to do the trick for her. If Trump were to win Iowa—and to parlay that into victories in New Hampshire, Nevada, and/or South Carolina—their hopes will be quashed and the primary will be over. Any chance of a consensus anti-Trump candidate emerging will have been steamrolled before Romney’s strategy even begins to take effect.

DeSantis’ campaign in particular almost certainly won’t survive a defeat in Iowa since there’s no reason to think he’ll fare better in New Hampshire or South Carolina. If you’re eyeing him as the Not Trump option in a two-man contest, the Great Donor Consolidation needs to happen long before the caucuses take place, not after.

Another problem with Romney’s 2016 analogy comes from the headline of his op-ed: “Donors, Don’t Fund a Trump Plurality.”

Plurality?

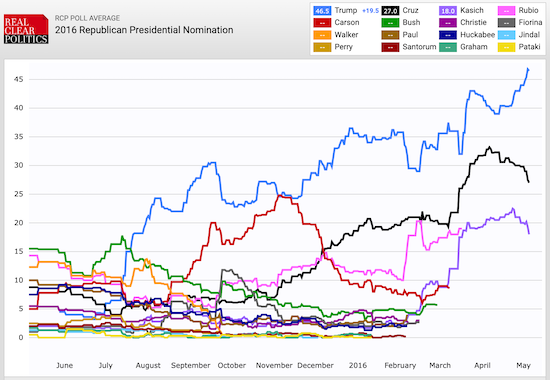

Mitt’s history in this case is correct. Trump was a plurality candidate throughout the 2016 primary; the final RCP average after Ted Cruz dropped out of the race left the presumptive nominee with just 46.5 percent of the vote. In that year’s early contests Trump got 24.3 percent in Iowa, 35.2 percent in New Hampshire, and 32.5 percent in South Carolina before winning the Nevada caucuses with a comparatively robust 45.9 percent. That added up to three victories and tons of momentum despite only even approaching a majority in one state. That’s the Romney nightmare scenario for 2024.

But 2024 is different.

Trump hasn’t been below 50 percent in the national average since early April, after he was indicted in Manhattan over the Stormy Daniels matter. On April 4 the right-wing backlash to the indictment pushed him upward to 50.8 percent and he’s enjoyed majority support ever since. He’s less formidable in early-state polling, especially New Hampshire, but is scoring in the mid- or upper 40s in Iowa and South Carolina, leaving him on the cusp of majorities there too.

Recently, in a column titled “Why the 2024 GOP Primary Isn’t Like 2016,” Amy Walter crunched the numbers to show how much more popular and formidable he is among Republicans now than he was when he first ran for president. In July 2016, after he’d clinched the nomination, Trump’s net favorability within the party was +36; as of last month, it was +60. When Republicans were asked in the summer of 2015 whether the GOP would stand a better chance of winning with him or with someone else, he finished 20 points underwater. Last month he was slightly net positive in that metric.

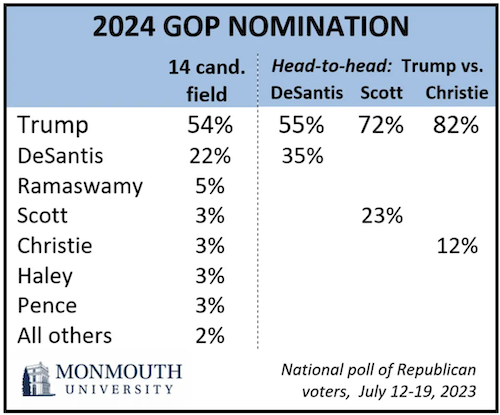

This morning Monmouth published a new poll in which it asked primary voters how they think Ron DeSantis would fare against Joe Biden relative to the frontrunner. Nearly half said the governor would be a weaker candidate than Trump while another 26 percent thought he’d be equally strong but no stronger. That’s nearly three-quarters of Republicans who remain unsold on DeSantis’ “electability” pitch, the crux of his campaign. When asked who the strongest Republican against Biden would be, 45 percent said “definitely Trump” while another 24 percent said “probably Trump.”

To the extent Romney’s Great Donor Consolidation strategy calls for uniting behind a candidate who can actually win the general election, in other words, most of the GOP base seems to believe that’s … Donald Trump.

There’s a third problem with Mitt’s comparison between 2016 and 2024. National polling in the 2016 primary looked like this:

Trump led consistently but that contest was a dynamic one. The second-place candidate was within 15 or so points of him at all times and numerous contenders had surges, demonstrating real momentum. Ben Carson briefly passed Trump in early November before being overtaken by Ted Cruz, and Marco Rubio’s polling doubled overnight after he fell just short of Trump in Iowa. The Great Consolidation Strategy, if executed at an opportune moment to benefit Carson, Cruz, or Rubio, might have sent their polling skyrocketing and changed the outcome of that primary.

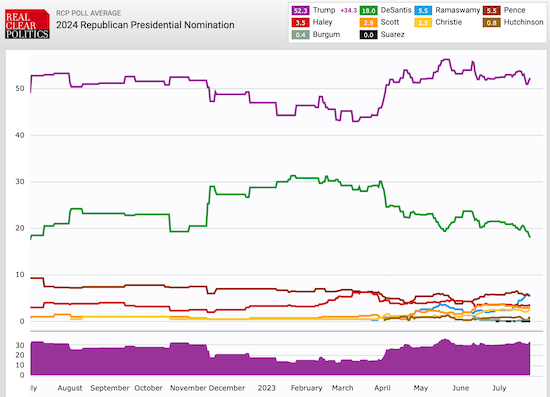

National polling in the 2024 primary, on the other hand, looks like this:

What we have here, to borrow a term from modern Russian warfare, is a frozen conflict. With the notable exception of Vivek Ramaswamy, not one candidate is polling meaningfully better than they did at the start of the summer.

The race has been Trump 50, DeSantis 25 for a year, in fact, apart from a bounce for the governor following his landslide victory in the 2022 midterms and a slide following Trump’s indictment in Manhattan at the end of March. Under the circumstances, it’s unclear when and how a well-timed Great Donor Consolidation might have occurred to upend the race to DeSantis’ benefit.

That’s especially true when you recall that many donors have already consolidated behind DeSantis. The governor’s campaign and his chief PAC raised more than $200 million combined last year for his reelection bid in Florida, an outlandish amount for a state race that was never competitive. His new federal PAC raised more than $30 million in less than a month after launching this past spring and DeSantis’ campaign led all others, Trump’s included, with more than $20 million in contributions in the last quarter.

That’s not the total donor consolidation that Romney is hoping for, impressive as it is. Tim Scott, for instance, is raking in big bucks from wealthy patrons of his own and is planning to put them to good use in the early states. But DeSantis has spent the past year as the golden boy of the Republican donor class, who see in his youth, his populism, and his alleged electability a candidate who might at last woo the Republican base from Trump. Many right-wing donors are way ahead of Mitt in lining up behind the governor as a potential consensus alternative to a frontrunner who’s unfit for office.

You can see from the graph above how well it’s worked out.

Perhaps that’s because the governor is an underwhelming retail presence, perhaps it’s because the coalition he’s built is untenable, perhaps it’s because the 2024 Republican contest is functionally a primary challenge to an incumbent president—another way in which this cycle differs starkly from 2016.

Whatever the answer, the hard fact remains that DeSantis is both the highest-polling alternative to Trump and a candidate with a clear downward trajectory. Good luck calling for a Great Donor Consolidation when it’s suddenly less clear than ever whom, precisely, those donors should be consolidating behind.

As chance would have it, the Monmouth poll I mentioned earlier tested how various challengers would do in the sort of two-man race with Trump that Romney covets. Again: If you’re worried about Trump winning a plurality victory this cycle, you’re fighting the last war.

Trump 55, DeSantis 35. To return to our earlier analogy, that smacks of a political illness that’s already terminal. Donors might be able to keep the governor alive and kicking for a while with huge cash infusions, but remission is unlikely.

And as grim as that seems, it’s even grimmer with a moment’s thought. Not only does a one-on-one race with DeSantis fail to erase Trump’s majority in Monmouth’s data—the fact that he fares so much better against Tim Scott and Chris Christie head-to-head reminds us that many of the governor’s supporters would swing behind Trump if their candidate quit the race.

Which seems like a fatal flaw in the Great Donor Consolidation strategy.

Romney’s demand for donor unity behind a single challenger tacitly imagines that voters who are supporting other candidates will rally en masse to that challenger as the field clears. That’s another relic of 2016 thinking—pro-Trump minority versus anti-Trump majority!—but it just ain’t so. Trump is the second choice of many Republican voters who favor other contenders, enough so to put him over 50 percent in Iowa and South Carolina when first- and second-choice polling are combined.

DeSantis voters in particular seem likely to switch back to the former president. The governor is, after all, running as “Trump but electable” and has adopted the same postliberal ethos that Trump mainstreamed. If you’re Team Ron because you enjoy watching him wage remorseless culture war against progressives, the MAGA O.G. is a much better fit for you as a back-up option than a holdover from the pre-Trump era of Republican politics. Hence Tim Scott’s dismal result against Trump in Monmouth’s polling once DeSantis is excluded as an option.

All of which is a long-winded way of making the familiar point that the modern GOP is two parties under one banner (with two distinct primaries, even!). Voters from one party don’t really want to support a nominee from the other.

Including perhaps Mitt Romney, the Great Consolidation advocate. Consider again his bizarre February 26 deadline for donors to abandon no-shot Republican candidates.

Romney knows, of course, that that’s too late to unite behind an alternative to Trump. He’s a former party nominee; he understands polling momentum and the significance of the early primaries. Why would he float a timeline that palpably wouldn’t work?

I think it’s because he doesn’t want to be forced to unite behind Ron DeSantis, a leader of the populist Republican Party. Romney, a statesman in the conservative Republican Party, wants to give fellow conservatives Nikki Haley and Tim Scott every chance to emerge as the last Trump alternative standing.

If he called for uniting behind a Trump alternative now, he’d be all but obliged to endorse Florida’s postliberal governor as the highest-polling challenger. By calling instead for uniting after South Carolina, when DeSantis may have already washed out of the primary, he’s giving Scott and Haley the opportunity to hold onto their donors for as long as possible, notch a big win in their home state, and turn Super Tuesday into a de facto one-on-one death match between Trump and a traditional conservative.

That wouldn’t work out well for either of them, I fear. But perhaps Mitt thinks it’d be better for the party and for conservatism in the long term if a figure from the pre-Trump era ended up outlasting DeSantis in the race. A Trump-Scott or Trump-Haley winnowing would show populists that conservatives remain a force within the party and must retain some influence over its direction in order to keep them inside the tent. (Or so Mitt might think. In reality, most conservatives are cheap dates and will roll over for anyone with an “R” after their name.) Whereas a Trump-DeSantis winnowing would extinguish what little is left of conservatism, leaving the future of the GOP a dismal choice between Trumpism and Trumpism but more so.

If that’s what Romney’s up to with his February 26 deadline, then his call for a Great Donor Consolidation is disingenuous. He’s not demanding an urgent, all-hands-on-deck effort to beat Trump; he recognizes that that will fail and that DeSantis and populism would benefit from the effort. His delayed timetable seems like an attempt to secure a moral victory amid another bitter defeat. If the campaign ends with a conservative in second place, and possibly on the presidential ticket, that’s the best a traditional Republican can hope for. He’s probably right.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.