The Alabama Legislature voted overwhelmingly late last week to provide blanket immunity to IVF clinics from any civil or criminal liability related to the death or damage of a human embryo.

While the legislation has been hailed across the media as a measure protecting IVF access, it accomplished this goal by stripping away legal protections for IVF patients whose embryos are negligently destroyed. “[N]o action, suit, or criminal prosecution for the damage to or death of an embryo shall be brought or maintained against any individual or entity when providing or receiving goods or services related to in vitro fertilization,” according to the text of HB 237, a bill that passed the Alabama House 94-6 on Thursday with three abstentions. The Alabama Senate unanimously passed a nearly identical bill that same day, setting up a signature from Alabama Gov. Kay Ivey in the coming days.

Alabama lawmakers passed the bills less than two weeks after the state Supreme Court issued a ruling holding that a fertility clinic could be sued for the negligent destruction of embryos under the state’s Wrongful Death of a Minor Act. The speed with which the legislature moved can be attributed to two main factors. First, following the Supreme Court ruling, at least three of the eight IVF clinics in Alabama paused treatment as they evaluated legal risks, placing some IVF patients in limbo. Second, Republicans in Alabama and nationwide are running scared from false accusations that the Alabama ruling is the result of the 2022 Dobbs Supreme Court decision and false claims Republicans want to ban IVF, a treatment that enjoys overwhelming popular support. In response to those accusations, on February 23, presumptive GOP presidential nominee Donald Trump urged Alabama’s legislature to act “quickly,” and lawmakers answered that call by introducing legislation on February 27 and passing it on February 29.

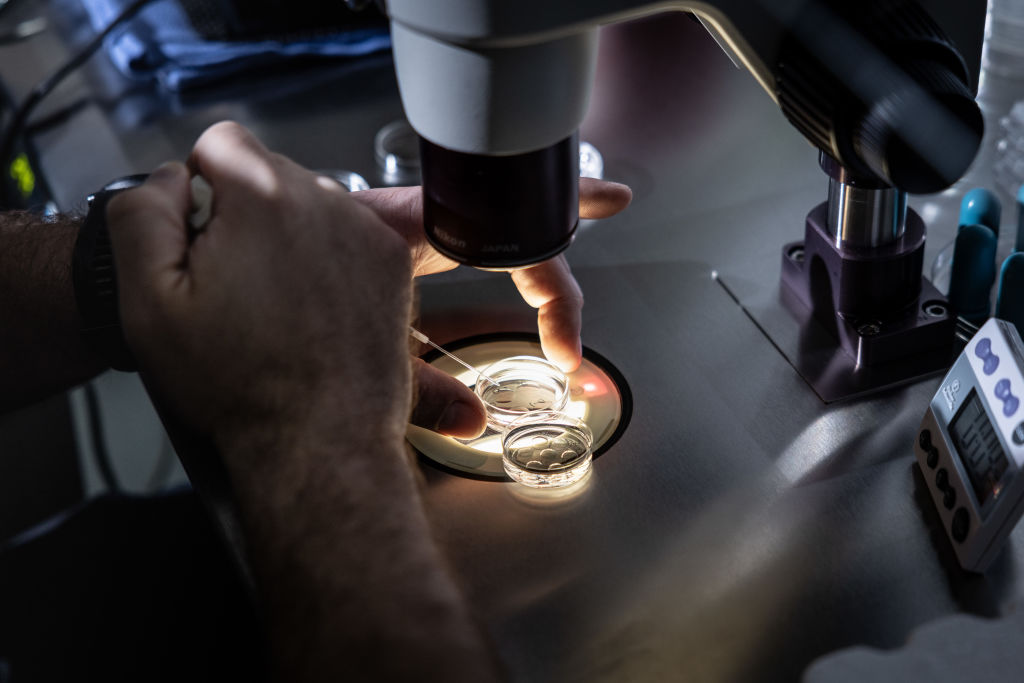

But there are perils to lawmaking at warp speed in a fit of political desperation amid a media firestorm—especially on an ethically complex issue. The immunity granted by the legislation would be sweeping and absolute, as it applies to “any individual or entity” who damages or kills a human embryo “when providing or receiving goods or services related to in vitro fertilization.” The case before the Alabama Supreme Court, for example, involved wildly negligent behavior: Three sets of parents sued a clinic after their embryos were killed when a random hospital patient wandered into a cryogenic nursery through an unsecured door, accessed the stored embryos, and dropped the vials containing the embryos.

The proposed law would apply “retroactively to any act, omission, or course of services which are not the subject of litigation on the effective date of this act.” So it would allow those three sets of parents to continue to have their day in court, but it would not provide legal recourse to other IVF patients who experienced similar or worse treatment—no matter how negligent or willful. In an email to The Dispatch, Notre Dame law professor Carter Snead warned that the blanket-immunity legislation “will have catastrophic results, including a cascade of unintended harmful consequences for IVF patients.” There have been horror stories all around the country in which couples have had their embryos negligently destroyed, and successful lawsuits against those clinics have not threatened the availability of IVF. In 2021, for example, a California jury awarded $15 million in damages to couples whose embryos were destroyed—a decision that did nothing to curtail IVF access in the state.

Snead, who served as general counsel on the President’s Council of Bioethics during the George W. Bush administration, urged the Alabama legislature to “slow down and study this highly complex question carefully.” But there’s no sign of anyone in Alabama hitting the brakes on the legislation, even as state lawmakers across the aisle acknowledged problems with the bill but portrayed it as a stopgap measure that would reopen all IVF clinics as they considered the matter more carefully. “Republican and Democratic lawmakers raised concerns that the ‘immunity’ offered to medical personnel treating IVF patients was too broad and risked leaving women who are injured or adversely affected during care without recourse,” according to an NBC News report on the legislature’s floor debate on the bills. “There are parts that are still missing,” Democratic Rep. Adline Clark said. “Major parts.” As first introduced, the legislation contained a sunset provision in March 2025 in order to force such a reconsideration, but lawmakers dropped it over concerns it could interrupt treatment for IVF patients.

If there is a way for Alabama GOP lawmakers to thread the needle here—providing some legal recourse for IVF patients while upholding pro-life principles and ensuring all IVF clinics stay open—they certainly haven’t found it yet. The national pro-life group Susan B. Anthony Pro-Life America urged Alabama’s legislature to copy a 1986 Louisiana law that allows IVF yet prohibits the intentional destruction of viable embryos. But that plea has fallen on deaf ears in Alabama for now. IVF often (but not always) involves the creation of several embryos at once, and those that aren’t immediately transferred to be implanted are cryogenically frozen and stored. One Louisiana IVF doctor told the Associated Press he and others get around the state’s prohibition by keeping frozen embryos stored out of state and shipped back in if and when they are desired.

“We find it unacceptable,” said SBA’s Katie Glenn Daniel, that the Alabama legislation “would create these blanket protections for the IVF industry at the expense of unborn children and of their parents.”

Republicans in Alabama and Washington, D.C., and even pro-life groups, were caught flat-footed by the Alabama Supreme Court ruling because there’s never really been a serious debate about IVF in this country. That lack of debate has been due to the treatment’s overwhelming popularity, as well as the fact that the ethics—not to say the legality—of creating embryos through IVF has always divided the pro-life movement. See, for example, this 2019 debate between two pro-life evangelicals who argue against IVF and one evangelical who argues in favor of it “as long as no human embryos are destroyed in the process,” something that can be accomplished but may ultimately incur greater costs and multiple procedures. While orthodox Catholics believe IVF is ethically wrong, there is an intra-Catholic debate about embryo adoption. One doesn’t need to have religious convictions, of course, to be concerned about ethical questions surrounding the treatment of nascent human life: Secular Germany passed the 1990 Embryo Protection Act that limited the number of embryos that may be created and transferred in one treatment (a law that has plenty of critics and its own unintended consequences).

In the United States, pro-life groups have never favored banning the creation of human embryos through in vitro fertilization. They have, however, always been concerned about the destruction of human beings in the earliest stages of development. But the last time there was a serious political debate touching on the issue was the George W. Bush era, and even then the debate in Congress narrowly focused on matters such as banning human cloning and prohibiting taxpayer funding of scientific research that required the destruction of new embryos.

Two weeks after the Alabama Supreme Court forced the issue to the forefront, the Alabama Legislature has found a solution to its political problem but deferred a serious debate about the deeper issues at stake to another day. “My goal this week has been to try to find some compromise that would open our clinics for these families,” Republican state Rep. Terri Collins, sponsor of the House bill, said on Thursday. “Do we need to have the longer discussion? Yes, we do.”

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.