Happy Sunday and to those celebrating this week: Merry Christmas! Or, Happy Hanukkah!

This year is unusual in that for only the fifth time in the last 100-plus years, the first night of Hanukkah falls on December 25. Christian theology professor Ephraim Radner thinks that’s a natural time to examine what makes each holiday distinct in order to resist both ill-fitting attempts to draw parallels between the two and a common enemy they share: overcommercialization.

Whichever holiday you may be celebrating this week, I hope it is joyous, peaceful, and heartening. Thanks for spending your time with The Dispatch.

Ephraim Radner: Christmas and Hanukkah: Distinct Holidays With a Common Challenge

I’m a fairly straightforward traditional Christian. An ordained Anglican priest, congregational pastor and theology teacher, I have followed my church’s religious customs pretty consistently and relatively strictly. But I also have a partly Jewish background, and have always been interested in Judaism’s religious commitments. Of late I’ve even become involved with a range of Jewish-Christian and Messianic Jewish disciples of Jesus. Take all of this together and the seasonal conjunction of Christmas and Hanukkah carries a certain challenge—coincidence or providence—especially as the first night of Hanukkah this year begins on Christmas Day. That conjunction appeals to more than a few religious folk, who would like somehow to bring these two festivals together if only for the sake of softening the distance between Christianity and Judaism.

Yet I have come to the conclusion that the two holidays have little to do with one another, and trying to make them somehow complementary probably does a disservice to their intrinsic meanings and thus to the commitments each community holds in their celebration. Simply presenting some background to each helps bring out these profound distinctions, and at the least permits a better perspective for relating one to the other. The effort to make them complementary has also encouraged one of the main problems besetting each holiday: over-commercialization. Keeping both holidays distinct can help ward off what today constitutes their chief enemy.

Understanding Hanukkah.

Let’s start with Hanukkah. The name simply refers to “dedication,” and in this case, the specific event, in the year 165/164 BCE, when the Jerusalem temple was somehow “rededicated” to the Lord, following its desecration by the Greek ruler of the time, Antiochus Epiphanes. The story is recounted in the first book of Maccabees. The Books of Maccabees (there are several) were originally part of the Jewish Bible and translated into Greek perhaps in the second century BCE. But they were never part of the Hebrew scriptures—the Tanakh, or larger Jewish scriptural canon that fits, mostly, with what Christians call the “Old Testament.” So only some Christians ever read about the events behind Hanukkah, and Jews themselves celebrate on the basis of a national memory, not of Scripture.

The events behind Hanukkah go like this: Having led a successful revolt against the pagan occupiers, the priest Judas Maccabaeus liberated Jerusalem and purified its precincts from idolatrous worship to the Greek god Zeus that the pagan king Epiphanes had established within the temple. The altar was rebuilt, among other things, and the altar fire rekindled, with a time of rejoicing that lasted eight days. Talmudic sources provide a miraculous context to this rekindling, explaining that a single cruse of oil was found in the temple, still sealed and thus unblemished, preserved from the time of the early kings of Judah. Having opened and kindled the oil, this small lamp, that should have lasted at most a day, marvellously remained lit for eight.

The festival came to celebrate the divine miracle of Israel’s protection, restoration, and faithfulness, to be publicized before all Jews and the world. Hence, central to the festival is the display of “lights,” as in candles or groups of them on the more familiar candlesticks known as menorahs. The dating of the festival—on the 25th day of the ninth month, Kislew, according to the Jewish calendar (around our modern December)—was linked both to the day of the temple’s original profanation by Atiochus Epiphanes, as well as to a much earlier event, when Nehemiah lit the fire at the rebuilt temple following his people’s return from exile in Babylon.

Hanukkah is not really a “major” feast (since it is not mentioned in the Tanakh or Jewish scriptures). Though discussed in the Talmud and elsewhere, the festival’s traditions have thus been particularly malleable, local, and culturally specific in many ways: how the candles are lit, who lights them, numbers of menorahs and where they are placed in the house, benedictions and prayers, songs, food eaten, the role of children, gifts and so on. All of this has developed and varied enormously.

The festival’s focus has always been about the temple, law, purity, and divine mercy in restoring the Jewish nation’s formal devotions. And at the center of all this, certainly, is the joy of God’s renewing grace for the people of Israel and their worship: “And there was exceeding great joy among the people, and the reproach of the Gentiles was turned away” (1 Maccabees 4:58). Work is not prohibited on Hanukkah (except during the candle-lighting each night); and although there are some Hasidic traditions that have encouraged specific acts of repentance within the holiday, the time is one mostly one of delight and celebration.

Interestingly, the Maccabean political and military struggle that informs the history of Hanukkah was downplayed in Jewish celebrations until recent times. Now, however, this struggle has become an important element of Hanukkah’s remembrance, especially more popularly, stressing political resistance and liberation. Indeed, Hanukkah is about Jewishness, Jewish corporate existence and survival, and Jewish worship in comparison with other religious practices.

In America especially, Hanukkah has gained enormous prominence since the 19th century and even more so after World War II—both in civic recognition, but especially as a focus of Jewish family activity, including gift-giving. The most accepted theory about this has to do with the pressures of immigrant assimilation into American society (and it is in America that Hanukkah has seen its most visible flourishing as a holiday). Hanukkah provided a way for Jews in America to engage in a distinct Jewish festival so as both to retain a specific ethnic and religious identity, but also to link that up with the predominant Gentile customs surrounding Christmas.

Still, for all the attempts, real and imagined, at drawing Hanukkah into some kind of relationship with Christmas and apart from the central but general theme of God’s miraculous power and grace, the two festivals have almost nothing in common. Some of the often tortured theological fabrications to bring Hanukkah and Christmas together in religious terms include seeing Jesus as the light (like the light rekindled in the temple), or Jesus as the temple itself (using imagery from the Christian gospels). But to press these parallels is in fact to lose the very national, concretely Jewish, and politically fraught understandings that inform Hanukkah’s basic meaning. It is to de-Judaize Hanukkah and invent something else.

Another tired theory is to see each festival as a particular religious refashioning of pagan celebrations related to the winter solstice. Hanukkah’s date, as I noted, is traditionally linked to the earlier moment of the temple’s desecration by Epiphanes, as well as to the date when Nehemiah relit the altar fire at the rebuilding of Jerusalem. Christmas seems pretty clearly to have been the product of counting forward nine months from the already established celebration of Mary’s conception at the Annunciation, traditionally dated on Mach 25 (though the evidence of these datings and the theories relating them are complicated and clouded).

Understanding Christmas.

So, let us turn to Christmas. Whatever the rationales behind its most remote origins, we can clearly see that, by the fourth century, the general celebration of Christ’s birth—the Nativity—was established, and usually held in late December. There were some complex calendrical disagreements that arose between Western and Eastern churches, but many (though not all!) Eastern churches now celebrate Christmas on the same day as in the West, on December 25.

Some of the impetus for establishing the Feast of the Nativity in the early church came from assertions of orthodox belief in a fully divine Incarnation—Jesus was the Son of God, in the flesh. This claim came in opposition to those Christians who denied the full divinity of Jesus. Furthermore, other feastdays, observances, seasons, and commemorations grew up around the Nativity, turning the actual day of Christmas into just one moment (though a central one) in a grand depiction of Jesus’ life. That depiction would finally include the full year’s liturgical celebrations of the ministry, passion, death, resurrection, and ascension as well.

Already observed somewhat by the fifth century, the season of Advent, for instance, was fully ensconced in the Western church by the Middle Ages—usually four weeks of fasting before Christmas, and focusing on Christ’s second coming and judgment as well as the preaching of John the Baptist, including the story of the Annunciation to Mary. By the fourth century, as well, Christians commemorated Christ’s baptism, and later also the visit of the wise men, observed on or around the same time as the Nativity. These were eventually decoupled into separate feastdays, with January 6 as the Epiphany or “manifesting” of Christ before the nations and people of Israel. The “12 days” between Christmas and Epiphany marked the Nativity season. Later on, the association of St. Nicholas Day, on December 6—Nicholas, according to legend, was a miracle-working protector of children—with gift-giving, was merged with Christmas itself. Thus St. Nicholas literally became the “Santa Claus” of modern north European tradition.

It is important to see how completely distinct all this is from the specific interests of Hanukkah. Indeed, the Christian claim that Jesus of Nazareth is the messiah of Israel, let alone the incarnate son of the living God, stands as an affront to the expectations of Jewish religious belief, and on a host of levels. Hanukkah’s purifying of the temple from idolatrous worship would, for most Jews, preclude any embrace of Christian claims about a trinity, a divine God-Man, and the abrogation in such a person’s life, death, and resurrection, of the law the God graciously gave to Israel.

The Nativity accounts in the gospel of Luke especially, and the events surrounding Jesus’ birth told in Matthew, play a determining role in the church’s quite extensive religious traditions surrounding Christmas: the focus of the feast is on Christ’s humility as the God who stoops to human form (as in Philippians 2), on Mary’s faith, on the incarnate God’s vulnerability in the face of Herod’s plots, on the message of hope to the poor, like the shepherds, and on the gift of life offered to the nations (and of Israel’s stirring opposition to this gift). All these are traditionally prominent in Christmas prayers, liturgies, and preaching, and, apart from the general overlap in interest in God’s grace, are quite distinct from Hanukkah themes. Among the great Western sermons on Christmas in this regard are those by the fifth century pope Leo the Great and the 17th century Anglican Lancelot Andrewes. An extraordinarily rich set of musical traditions developed, largely in Western Europe, during the Middle Ages and early modern period—carols, hymns, elaborate church cantatas and oratorios—along with a host of local customs in food and domestic decoration.

Resisting commercialization in both.

Whatever the differences in liturgical custom between Eastern and Western Christians, and between Catholics and Protestant, one development is clear, and in the West particularly: the takeover of Christmas by the “market.” Today, all Christian practice and worship has been engulfed by cultural and commercial interests. These began to assert themselves strongly by the later 19th century, but they are now the hovering umbrella of all December activities. These commercial forces are by now both recognized by all, and mostly acceded to by all. On this score, Jews and Christians have unwittingly come together. Hanukkah and Christmas both, that is, are festivals subject to challenges that are far broader, socially, than those associated with particular religious communities: Mammon!

Any effective resistance to this idol—money, greed, indulgence—will demand cooperation by Jews and Christians together in our society. And against such idolatry, the religious values of Hanukkah and Christmas, at least in their unalloyed essence, are perhaps necessarily deployed. After all, purity of covenantal devotion on the one hand, and divinely empowered humility of self-giving on the other, are powerful antidotes to the seductions of wealth.

These values, however, are not quite the same. To use them rightly, we must identify them accurately, appreciate them in their particularity, and embody them with the integrity of their character. Permission and patience in this regard are gifts that Jews and Christians might rightly offer one another. We can then wait and see what, in the process, providence provides.

John and Lauren McCormack: How We Named Our Daughter

Regular Dispatch readers may have noticed one byline has been absent in recent weeks: that of senior editor John McCormack. That’s because earlier this fall, after years of infertility, John and his wife, Lauren, welcomed a beautiful baby girl! On the site today, they share in a heartfelt essay why the birth of little Mary Elizabeth was so joyous for them—and why the fourth Sunday of Advent is a day particularly filled with gratitude for them. Be warned: You may want tissues handy when reading.

Adoption is a beautiful gift that brings goodness out of tragic circumstances—a gift that has already blessed our extended family. But we kept delaying serious plans for adoption because the process can be stressful, and we were concerned stress could contribute to infertility. The year 2024 seemed like a natural deadline for us. John would turn 39 in January, and when life expectancy was shorter, some adoption agencies would not let prospective parents older than 40 adopt. Even today, when birth mothers typically choose adoptive parents in cases of domestic infant adoption, they reportedly favor relatively younger parents. And with each of us approaching an age when fertility naturally declines more steeply (Lauren would turn 36 in the spring), the time seemed right to adopt.

Then a series of surprising events occurred.

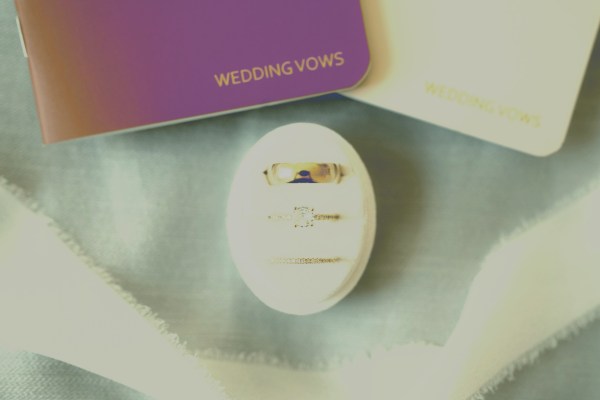

John and Lauren learned they were expecting. Though the pregnancy was stressful and not without anxiety, Mary Elizabeth was born earlier this year.

We think Our Lady has always been watching out for us ever since we met on a blind date that occurred by happenstance on the Feast of the Annunciation. On Easter in 2022, we visited Lourdes, France, a Marian holy site known for miraculous healings. And the very month before Mary Elizabeth was conceived after a decade of infertility, we participated in our diocese’s novena to Our Lady of Guadalupe for couples struggling with infertility, miscarriage, and early infant loss.

The Dispatch Faith Podcast

This week’s Dispatch Faith guest is Ephraim Radner, who joined me to discuss his essay this week on Hanukkah and Christmas, his family background—his father grew up Jewish but converted to Christianity, and his mother was raised Catholic—and how believers can resist the temptations of overcommercialization of both holidays. These weekly conversations with Dispatch Faith contributors are available on our members-only podcast feed, The Skiff. If you want to hear those more in-depth conversations with Dispatch Faith writers, join us!

More Sunday Reads

Longtime foreign affairs reporter Mindy Belz (and, full disclosure, a personal friend and mentor) reported last week on her Substack Globe Trot on the precarious position Syria’s new political reality puts some religious and ethnic minorities. “A Christian population estimated at 120,000, along with the remains of some of the oldest churches in the world, won protection in the autonomous zone. So have Sunni Arab tribes who opposed the Assad regime. Christian and Arab parties help to lead the region’s Syrian Democratic Council. Aramaic, the first-century language still used in the ancient churches, is an official language alongside Arabic and Kurdish. Many saw the zone’s governance structure as a potential model for a post-Assad Syria. Now its future is less clear. Turkey has assaulted the region since Assad lost power, seeking to expand its buffer zone against what comes next. So have U.S. and Israeli forces. President Joe Biden said he was ‘clear-eyed’ about the possibility of an ISIS resurgence and targeted Assad’s military installations with at least 75 air strikes this week, while Israeli forces hit suspected chemical weapons arsenals before they could fall into militant hands. Repeated Israeli strikes on Syria throughout recent months not only degraded Hezbollah and Assad’s support for militants targeting Israel, but paved the way for [Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS)] to overtake Assad’s military. Meanwhile, HTS on Dec. 10 said it had taken control of Deir Ezzor, fighting the U.S.-backed Kurdish forces that only days before took it from Assad’s Syrian army. HTS says it will take other cities in the northeast too, but it’s unclear whether it will take on Kurds in the autonomous zone and their allies to do it. HTS leader Abu Mohammed al-Jawlani vowed at the outset to reassure Christians and other religious minorities that he embraced pluralism in a post-Assad Syria. His group since 2022 has helped to rebuild and reopen churches in Idlib. I talked to one source who confirmed that Christians in Aleppo received similar assurances. But al-Jawlani (also Jolani or Julani) brings to the table a checkered past. … For now, one Assyrian Christian leader told me, ‘We have questions rather than answers.’”

A Good Word

Over at the New York Times, Pope Francis—yes, Pope Francis—has a column on humor, in which he pokes more than a little fun at himself and other popes. It’s worth the read! “Jokes about and told by Jesuits are in a class of their own, comparable maybe only to those about the carabinieri in Italy, or about Jewish mothers in Yiddish humor. … I remember the one about the rather vain Jesuit who had a heart problem and had to be treated in a hospital. Before going into the operating room, he asks God, ‘Lord, has my hour come?’ ‘No, you will live at least another 40 years,’ God says. After the operation, he decides to make the most of it and has a hair transplant, a face-lift, liposuction, eyebrows, teeth … in short, he comes out a changed man. Right outside the hospital, he is knocked down by a car and dies. As soon as he appears in the presence of God, he protests, ‘Lord, but you told me I would live for another 40 years!’ ‘Oops, sorry!’ God replies. ‘I didn’t recognize you.’”

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.