This man also took the view that the symbol of Christianity was a symbol of savagery and all unreason. His history is rather amusing. It is also a perfect allegory of what happens to rationalists like yourself. He began, of course, by refusing to allow a crucifix in his house, or round his wife’s neck, or even in a picture. He said, as you say, that it was an arbitrary and fantastic shape, that it was a monstrosity, loved because it was paradoxical. Then he began to grow fiercer and more eccentric; he would batter the crosses by the roadside; for he lived in a Roman Catholic country. Finally in a height of frenzy he climbed the steeple of the Parish Church and tore down the cross, waving it in the air, and uttering wild soliloquies up there under the stars. Then one still summer evening as he was wending his way homewards, along a lane, the devil of his madness came upon him with a violence and transfiguration which changes the world. He was standing smoking, for a moment, in the front of an interminable line of palings, when his eyes were opened. Not a light shifted, not a leaf stirred, but he saw as if by a sudden change in the eyesight that this paling was an army of innumerable crosses linked together over hill and dale. And he whirled up his heavy stick and went at it as if at an army. Mile after mile along his homeward path he broke it down and tore it up. For he hated the cross and every paling is a wall of crosses. When he returned to his house he was a literal madman. He sat upon a chair and then started up from it for the cross–bars of the carpentry repeated the intolerable image. He flung himself upon a bed only to remember that this, too, like all workmanlike things, was constructed on the accursed plan. He broke his furniture because it was made of crosses. He burnt his house because it was made of crosses. He was found in the river.

G.K. Chesterton The Ball and the Cross, 1909

The inverted cross is the sign of our times—not because it stands for some kind of serious evil but because it stands for unserious evil: shallow, sophomoric, self-indulgent, and, above all, derivative. It has no power—and no content—of its own, only that which it borrows. Its fundamental character is parasitic. It can be deployed as a simple insult, or as satire or parody, but never reaches anything higher or more interesting than that. And the great limitation of satire is that its power dissipates when knowledge of the thing being satirized fades. The annihilating kind of satire or parody is a joke on a suicide mission. It cannot live on its own; it requires a host organism.

And the one it has—our culture—is not in especially good health.

We may live in a society that thinks of itself as morally and intellectually post-Christian (though it is no such thing), but aesthetically we remain fascinated by—practically hostage to—Christianity, its images and its stories. Popular culture from television to film and pop music to best-selling novels to fashion to journalism to supposedly high art from generation to generation seems to do little else but recycle Christian imagery. Andy Warhol, a genuinely original genius, was up to his wig in Christian imagery, but, then, so are banal cabaret artists such as Madonna and Donald Trump. Political propagandists and power-worshippers have simply occupied Christian churches, as in the French Revolution and its Cult of Reason, or built mock “cathedrals” to their causes, or appointed themselves the heads of their churches, as Henry VIII did and Charles III has, carrying on the tradition.

When Esquire wanted to depict Muhammad Ali as a martyr, the art director did not borrow an image of Yasir ibn Amir—he made the great boxer into St. Sebastian.* Dan Brown didn’t make his private-jet money typing illiterate imbecility about imagery associated with Marxism or feminism or Unitarian Universalism or Jungian psychoanalysis. If you want to make that Godfather money, that Exorcist money, that Star Wars money, you dip into the well of Christianity. And maybe you don’t think too hard about why that well seems to be bottomless. You can keep cashing the checks without ever having to figure that out.

That is not a matter of religious belief or of religious self-identification—it is a matter of civilization. At a critical moment in the Harry Potter books, the hero visits the grave of his parents, upon which is engraved a line from 1 Corinthians: “The last enemy that shall be destroyed is death.” Which is natural, as J.K. Rowling explained: “They’re very British books.” It is not a matter of mere happenstance that “very British” goes along with the New Testament rather than with Confucius or the Bhagavad-Gita or the Koran. “Very American” remains a close cousin of “very British,” of course, and so GQ went with St. Sebastian and not with a great Islamic martyr—no one in its intended audience would have understood the latter reference.

And, speaking of GQ, none of this Christendom-mining even requires basic religious literacy: Writing in that esteemed fashion magazine about the Star Wars prequels, Joshua Rivera describes the virgin birth of Anakin Skywalker as an “immaculate conception,” a phrase referring to a Catholic doctrine that has nothing at all to do with the virgin birth of Jesus. It may never have been quite true that the Golden Age of Hollywood was a case of “a Jewish-owned business selling Catholic theology to Protestant America” (the original source of the witticism is disputed), but it surely is the case that today a very large chunk of our pop-culture industry comprises religiously illiterate, ask-me-about-my-pronouns secular-minded types whose senses are arrested by religious habits, the saints and martyrs, the Eucharist, visions of Heaven and (especially!) Hell, monasteries, stained-glass windows, Latin phrases engraved in stone, celibacy, angels, crucifixions, etc.

In a similar way, I do not credit the idea that these angry Christopher (Who-topher?) Hitchens types are in any genuine sense atheists. A genuine atheist should be either indifferent or maybe a touch regretful. Our so-called atheists are more like the maniac in The Ball and the Cross—they cannot stop thinking about Christianity and see Christian influence everywhere, especially where it isn’t. (It will be amusing once they figure out that about half of the prominent placenames in these United States are explicitly Christian in origin, from Providence, Rhode Island, to San Francisco, California.) No, these so-called atheists are not non-believers—they believe, hard.

There is a reason they insist on replacing “A.D.” with “CE,” as though that would somehow change the fact that we number our very years from the life of Christ.* That isn’t disbelief: That is fanatical belief. For a point of comparison: I myself do not believe in astrology, and I think it is profoundly silly and just a little irritating that the Washington Post publishes columns by people who want to lecture me about “believing in science” while also publishing horoscopes, but the day I start a committee for the purpose of suppressing the publication of horoscopes, you’ll know that I have finally cracked. I do not believe in astrology and, discerning no power in it, do not obsess about it.

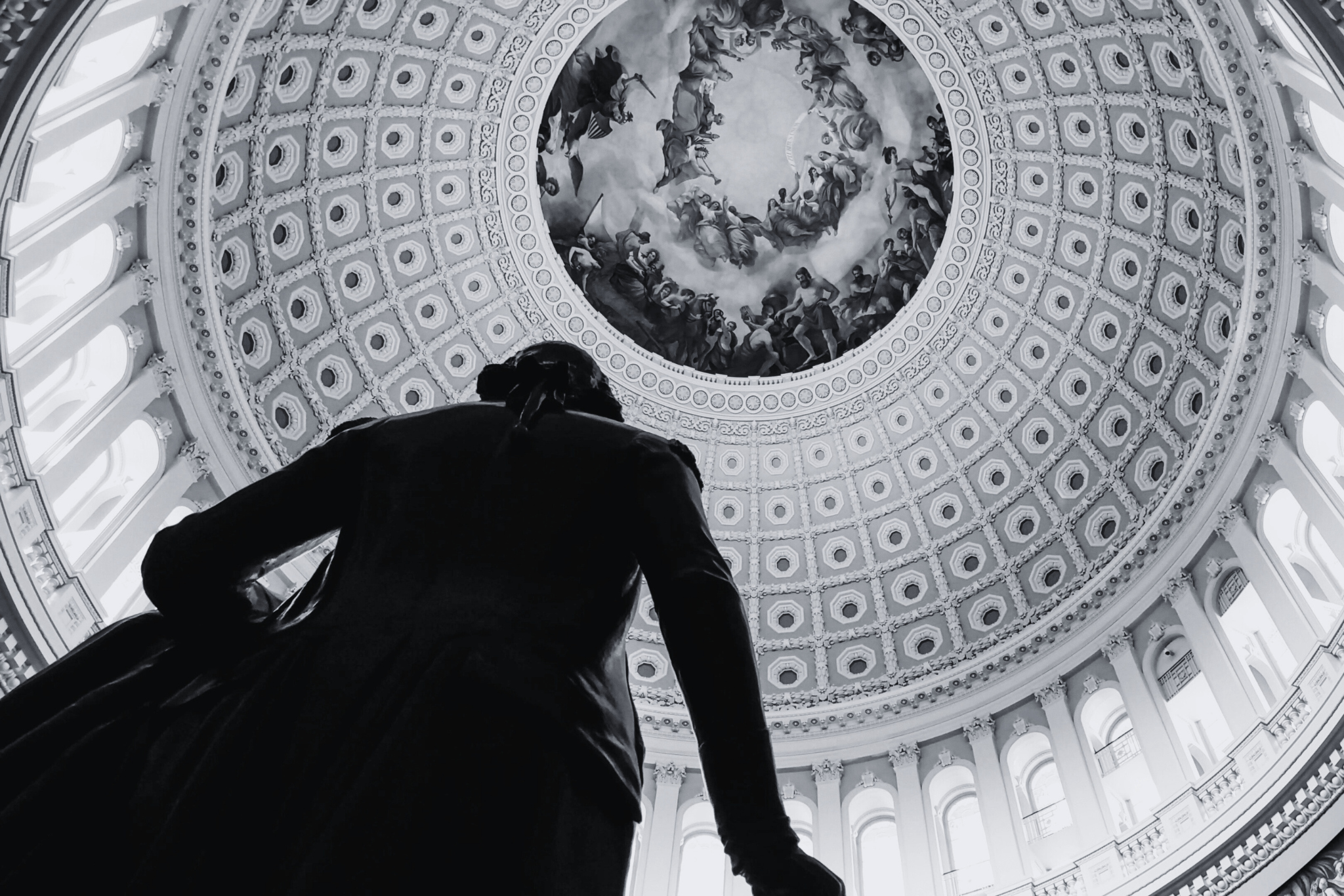

The pagan world, which still has a little juice in it, lives on in the background, and sometimes in the foreground: Washington, D.C., with its Augustan monuments to imperial power, is a much more thoroughly pagan city than Rome could ever hope to be. (If you want to see real atheists, you can find them in Rome, packed into the churches to gawk at the Caravaggios.) For years, Christian worship services were held in the U.S. Capitol, the dome of which is decorated on its interior with a painting of George Washington depicted as Jupiter and surrounded by Greco-Roman deities and deified American heroes. The American founders thought of themselves as the new Israelites, and, somewhere, Ramesses the Great is smiling as their descendants go about their political business in the shadow of the giant obelisk they built to commemorate the leader of their exodus. The pagan world retains some cultural cachet. We’re still making gladiator movies, and there is a reason for that beyond traditional homoeroticism. There is some aesthetic power left in the Greco-Roman tradition.

But there is much greater power in Christianity, and so we’ll spend at least part of this month fighting about the display of manger scenes in public spaces, or lamenting the vandalization of these scenes, or writing batty articles about why we should say “Happy Holidays” instead of “Merry Christmas.” And feelings get tender around these issues because of an uncomfortable reality that makes some good and decent people feel excluded: Of course this is a Christian nation, whatever Thomas Jefferson put in his letters.

It is a Christian country not because we have a Christian state (we do not have one, do not require one, and should not desire one), but because it is the product of a Christian society and a Christian civilization. None of those ever stopped being what it is simply because a lot of very influential people stopped believing in the religion itself while most everybody else continued doing what Christians have done for most of their history, i.e., affirming their belief in the nice and encouraging parts of the gospel while continuing to live like pagans. (And not even Dante’s “virtuous pagans”—far from it!) No, the Christian imprint on our society doesn’t come from polling data about what the average American believes in the waning days of Anno Domini 2024, much less from the average American’s behavior. Nor does it come from what the Bill of Rights says or from what Ruth Bader Ginsburg said it says.

Tradition, G.K. Chesterton wrote, is “the democracy of the dead. Tradition refuses to submit to the small and arrogant oligarchy of those who merely happen to be walking about.” Americans are uncomfortable with what that implies. The god of the American civic religion is something called “Fairness,” and Fairness requires that everybody be allowed to inhabit a world handcrafted ex nihilo to his specifications, a paradise in which no one is made to encounter or accommodate anything that is not of his own choosing or his own doing. The theologians’ project called “theodicy” consists of coming up with clever ways to pretend that Fairness and the God of floods and Egyptian plagues and Abraham and Isaac and all that blood and violence are basically the Same Guy.

No one hates hereditary facts—and Tradition—as intensely as the adolescent, and it is useful to understand that it was American popular culture that invented the idea of the “teenager” and then concluded that the best thing in life was to be one of those and to keep being one forever. The teenage mind may want to turn the cross upside down in protest, or to vandalize it, or to repurpose it, or insist that those who take shelter under it take up this or that position about gay rights or war or abortion or progressive income-tax rates. The derivative mentality can do anything with the cross except ignore it.

At one time, one might have made a persuasive argument that this was at least in part a defensive measure, because people who claimed to speak on behalf of the church or of the Christian tradition had a lot of power and wanted to use it to interfere in the lives of people who saw the world differently. But that has not been true for a long while—the era of Jerry Falwell and his ilk has been over for some time. The modern equivalents of figures such as Falwell are churchmen such as Robert Jeffress, who have shown themselves much more willing to bend themselves and their churches to the demands of political power than to try to do the opposite. That old explanation will not do. Things have changed.

Some people find it impossible to adjust to that new reality, which is how you get Slate reporting that the Federalist Society’s Leonard Leo is an arch-Catholic billionaire political kingmaker when in fact he is a non-billionaire lawyer and nonprofit administrator whose organization’s coffers were topped up with a $1.6 billion donation from Chicago businessman Barre Seid, whose background is Jewish. (Wrong conspiracy theory, guys!) The maniac in The Ball and the Cross ends up attacking roadside fences and his own furniture because there are crosses in the woodwork—our version of that is fretting about how Opus Dei secretly runs the FBI.

Tradition—but just a tradition? Because anything might become part of a tradition, as the persistence of pagan religious elements (Easter eggs, Christmas trees) in Christian cultures reminds us. Flannery O’Connor famously said of the Eucharist: “If it’s just a symbol, to hell with it,” and, if I thought that tradition were all there really is to Christianity—if I were one of those “cultural Christians” I’ve heard tell of, Elon Musk and the rest—then I might be tempted to say to hell with that, too. There is enough getting in the way of life’s little pleasures—you know: hatred, selfishness, the stuff that really feels good—without some dusty old Levantine wine cult’s getting in the way just because it (like Jonah Goldberg’s Animal House references) has a “long tradition of existence to its members and to the community at large.”

I’ve never made much effort to convince anybody of the truth of Christianity. There have been many, many words written to that effect, and a lot of them have been pretty dumb and, for that reason, probably have done more harm than good. The Case for Christ, for example, is a book so supernaturally dumb, so transparently dishonest in its account of the evidence, that one half suspects that it was infernally inspired to discredit more intelligent Christian apologists.

I have a few friends who are very into biblical archaeology and things like that, believing (or maybe only half-suspecting) that one of these days somebody is going to find an indisputable fragment of the True Cross or Noah’s ark or the manger in Bethlehem or something like that, and that all of the skeptics will, in that way, be put to shame. As it stands, we have very little contemporary documentary evidence outside of the gospels themselves that such a person as Jesus ever existed, much less that any of the stories that Christians tell regarding that episode are true. Just under half (or, depending on your tabulation, just more than half) of the books of the New Testament (amounting to about a quarter of the words) were written by Paul, who never claimed to have even met Jesus in the flesh during the ministry described in the gospels. If you put that very light stuff on one side of the scale and then load up the other side with the sheer unlikeliness of it all, the inconsistencies in biblical accounts of Jesus’s life and work, the apparent indifference (or at least reticence) of God in the intervening millennia—you are not going to make a lawyer’s case for Christ, or, at least, not a very good one. Nor will you make a good archeologist’s case or an astronomer’s case or an evolutionary biologist’s case.

And, if you try, you will be reduced to intellectual dishonesty, debater’s tricks, vulgarity, and nonsense. That isn’t how to go about it.

But, what to do, then?

I’ve often thought that one of the reasons Christian institutions and thinkers (like those belonging to many other religions) put so much work into creating beautiful things—churches, art, literature, drama, music, etc.—is because the aesthetic sensibility is adjacent to the religious one. Which is not to say that we should embrace Christianity because we admire Notre Dame or the Mass in B minor or Moby-Dick any more than we should embrace Islam because we admire the Shah Jahan Mosque or the music of Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan or the poetry of Al-Mutanabbi. (Or Judaism because we admire, what, half of the greatest American contributions to literature?) Without reducing it to a question of metaphysical utilitarianism, you don’t do push-ups to get good at doing push-ups—you do push-ups to get stronger. Art and literature and architecture aren’t there to be propaganda for Christianity, but there is a relationship there.

You don’t come to believe that Christianity is true the same way you come to believe that Smith has the better argument in the case of Smith v. Jones or in the way you come to believe that Apple shares are underpriced. It is more like—but not the same as—the way you come to believe that this painting or building is beautiful, that this man is admirable, that a certain friendship is suddenly very valuable to you, that you are in love.

And it is here that the strangeness of Christianity comes into play.

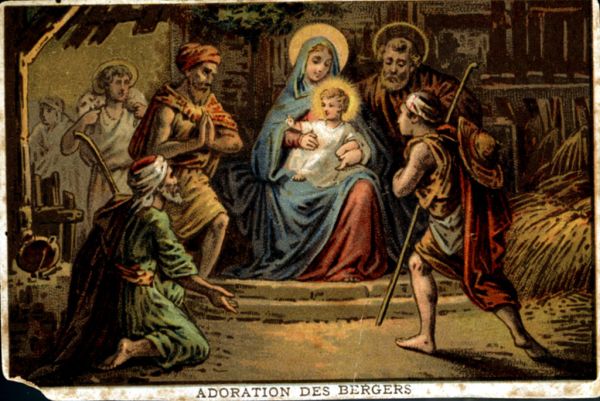

The Magi—the wise men from the east, the “three kings” in the popular tradition—aren’t there at the manger in Bethlehem. That is a conflation of different biblical events. They follow the star and arrive sometimes “after Jesus was born in Bethlehem of Judea,” entering “the house” to see “the Child with Mary His mother.”

When I think about biblical stories, I sometimes have to remind myself—and try to emphasize in my writing—that we are expected to believe that these are stories about real people, who, when they are not appearing as characters in Scripture, have the usual problems real people have: work, family, health, demands on their time, demands on their attention, demands on their financial resources, etc. Another way of saying that is that for every wise man who came journeying from the east, there probably was a wife or a boss or a brother-in-law back home who suspected that he was not so wise, after all, that he was off on some damned fool’s errand with his wise-guy friends, taking a long and no doubt expensive trip to some faraway land in order to observe—and financially support—events of no obvious immediate consequence to him or his family or his people or his community. You’re going where? To do what? Because you saw … a star? A star at night, in the night sky, you’re saying? In the place where you usually see stars? And you’re taking how much gold? And you’re leaving me here, alone, to do all the work and take care of the kids by myself?

The Magi make their journey, and what they first find is not Jesus but Herod—powerful and scheming, mean, fearful, meddling, full of jealousy and malice. He questions them and then obtains from them a promise of collaboration with his regime. The Magi move on. They press forward through the darkness, led in a way that is vague and mysterious but compelling, negotiate some difficulty with the secular powers, and then, after all of that complexity and complication, they encounter—what?

A child, Jesus. Not Jesus as a child—the Magi cannot see forward or backward along the timeline; what they know is what they have in front of them—simply, a child. The child has no particular urgent use for the gifts the Magi present, each of which corresponds to one of the child’s attributes: gold, for the king; incense, for the priest; myrrh, for the corpse of the sacrificial victim. Perhaps the symbolic value of these gifts was not immediately obvious to the Magi: These were expensive commodities and fitting royal gifts if only for that reason. What they could not have seen, except perhaps through the gift of divine insight, was that the gifts not only said something about Christ but also about their relationship to Christ as men: a king, a priest, and a sacrificial victim are those things only in relation to other men (subjects, worshipers, and those who are to be sacrificially redeemed) and on their behalf.

In that sense, the journey of the Magi presages the Christian journey itself. It begins with a persistent, urgent call, one that any entirely rational person—including the one being called—might reasonably suspect is a matter of fanciful misinterpretation and seek out a second opinion or a more moderate course of action. One then sets out into the darkness rather than out of it, into the night, with its mysteries, rather than into the cold light of day, when one might think better of these strange feelings. One encounters Herod, who is but one of many forms of the same adversary. One draws near to Christ and then encounters Him all at once, in the most (seemingly) simple of forms. One possibly glosses over the significance of the fact that He already was there, waiting for us. One gives such gifts as one has been able to carry so far in the night and its darkness, only to realize that He has no need of any such gifts, and that, in giving them, we come to understand what it is that we need.

It is not that doctrine and dogma are not important—it is that they come later and are subordinate. They do not lead us to the experience of Christ but only help us to understand it and to integrate it into our lives.

And, then, the hard part: “They left for their own country by another path.”

They traveled together, surely, at least for some of the trip, but each of them was now also traveling alone, having laid down the gold and the frankincense and the myrrh and taken up the much heavier burden of the truth, which is also the burden of the Cross but not only the burden of the Cross. And what was that star, after all?

Across my foundering deck shone

A beacon, an eternal beam.

Flesh fade, and mortal trash

Fall to the residuary worm;

World’s wildfire, leave but ash:

In a flash, at a trumpet crash,

I am all at once what Christ is,

Since he was what I am, and

This Jack, joke, poor potsherd,

Patch, matchwood, immortal diamond,

Is immortal diamond.

Immortal is a very nice word—the sound of it, the thought of it.

But that word, by its nature, points to the future. At least it does for us—for now. What falls to us in the present moment is to do what the Magi had to do after the remarkable encounter: find our way to our own home by another path, without anything so obvious as a new star blazing in the heavens to show us the way. We do not know the way. The night is dark and the roads are unfamiliar, and home is very far away. What we want is a sign—what we have is memory.

We remember what we saw that night, and we have the stories, which is how we remember together, how we remember in community. But we do not remember these things because we wish to embark on a program of self-improvement or a program of community-improvement, not because we care about “the culture” or because we believe that religious observance will lead to stronger families and healthier communities and a more glorious republic. As worthy and good as any of those things may be, what are they next to that scene in Bethlehem?

Outside, it is dark and cold. Inside, there is the firelight and the scene of love and life and warmth, the mother and father and child.

And then there’s us. The ones who have waited outside the longest are the most used to the cold and the dark, but we know where we want to be. Before we were the Magi, we were the shepherds, also called, also uncomprehending. What do we know? That if the manger is empty, then the tomb isn’t. We stop short, almost there, standing at the periphery of the scene, gripped by some kind of compulsion if not yet by belief, starting to figure out that the edge of the light and the edge of the darkness are, after all, the same place. And that is the place where we live and always have lived, and must live, for now.

“They left for their own country by another path.”

If that scene in Bethlehem is just a story, a pretext for moral instruction and a long weekend and time with friends and family and vague good feelings about generosity and kindness, then it would be better to forget about it altogether. You cannot build anything good on a foundation of lies, which is another word for nice old stories fortified with cheap sentimentality. You cannot make the trip to Bethlehem and then return to the east, reporting to your exasperated friends and family, “Well, it wasn’t really much of anything, but it’s going to inspire some very beautiful buildings in a thousand years, and some very good poetry, and some first-rate paintings. And the stories will make people feel like they should be nicer to one another, at least for a few weeks in winter toward the end of the year.”

Anno Domini: Either we number the years of our lives from the events at Bethlehem for a good reason or we don’t, and, if we don’t, we should knock it off. One way or another, we eventually will come to the end of our journey, and we will find exactly what the Magi were destined to find from the moment they first set their eyes on that star: Christ or nothing.

Corrections, December 26, 2024: This article originally referred to BCE rather than CE, and GQ rather than Esquire.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.