Rumors of the death of ideas have been greatly exaggerated. Our politics may run on vibes, and some combination of influencers and tribal loyalty may shape Americans’ intuitions. Yet there is still a throughline between ascendant ideas and important policy decisions.

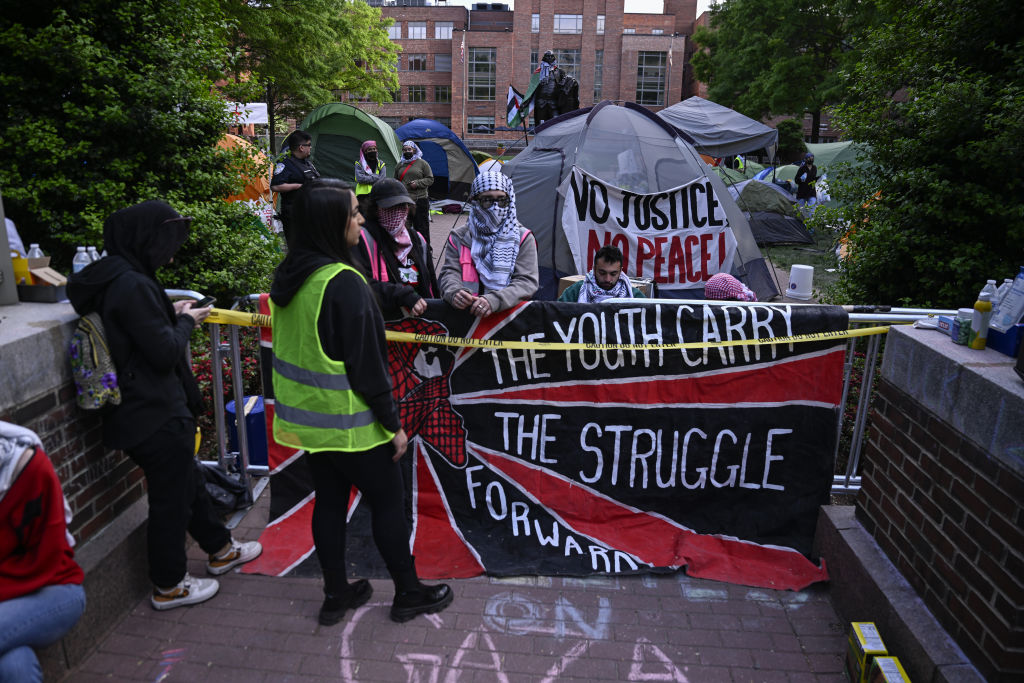

It can happen like this: Young people, their approval and votes coveted by tastemakers and policymakers, embrace an idea so exotic they cannot muster the lexicon or courage to question it; that idea shapes their general orientation toward a hot-button political issue, like race or the Middle East; political campaigns rush to capitalize on this new-found enthusiasm with some policy item that resonates with that orientation, like an arms embargo on an ally fighting a war against several enemy proxies.

As the terminus of that example suggests, unfortunately, most good ideas have already been around for a while, so the new ones with the power to dislocate our politics and culture tend to be bad. Indeed, as the literary critic Adam Kirsch examines in his recent book On Settler Colonialism, the exotic new ideas shaping young progressives’ view of the West are “disastrous”—intellectually indefensible, analytically facile, and prescriptively useless at best and murderous at worst.

Settler colonialism’s core stated insight is that “invasion is a structure, not an event.” Everything that happens in any place not ruled by “indigenous” peoples is an extension of that original sin. It is all “genocide”—and for some theorists, “it isn’t actually necessary for anyone to be killed in order for genocide to take place”. Even “reconciliation” between colonizers and colonized is genocide, because it is part of “the extinction of otherwise irreducible forms of indigenous alterity.” Peace and stability are thus vices, not virtues. Violence—of the kind celebrated euphemistically as “resistance” in the days after October 7, 2023, by those who have bought into these ideas—is progress.

Why the focus on Israel, though? The Jewish state was not founded after an invasion. Jews who had been exiled from their homeland rejoined the few who had never left. At worst, they and Arab tribes that had moved in during the intervening centuries have competing claims as “natives.” Yet “for the ideology of settler colonialism,” the conflict that has ensued has taken on a totemic quality, concludes Kirsch. As he displays through theorists’ strained analogies comparing Israel to every ill imaginable, “Palestine is the reference point for every type of social wrong.”

Kirsch’s chapter on “The Palestine Paradigm” is the book’s most valuable, revealing settler-colonial theory’s true face. Though it may appear at first as one garish float in a parade of increasingly radical movements for justice, somewhere between feminism and antiracism, it is really a spiritualist movement that relies on unfalsifiable axioms about the Romantic connection between the blood of certain people and the soil of certain land.

Kirsch points out that the other key term whose redefinition must be understood is “indigenous.” It was always a questionable way to refer to groups of people. Homo sapiens is a bipedal species; we did not spring forth from the ground like a cactus or a Douglas fir. To the extent any of us “belong” to a place, we are from a patch of land in East Africa. Then there is the ill-fitting but popular use of the term to mean “priority,” as in the case of Native Americans predating Europeans’ arrival. (Even this definition is fraught with analytical obstacles. For one, “Native American” is only a meaningful category from a Eurocentric perspective, and not to the tribes that warred and conquered one another.)

All of that goes by the wayside, precisely because Israel, bearing a title deed from millennia ago, would pass this test. “In the discourse of settler colonialism,” Kirsch explains, “indigeneity has a meaning beyond chronology. It is a moral and spiritual status, associated with qualities such as authenticity, selflessness, and wisdom. These indigenous values stand as a reproof to settler ways of being, which are insatiably destructive.”

To the academic wing of the anti-Israel brigades, then, Palestinians must be some kind of combination of Pocahontas and John Brown. Academic Steven Salaita writes that Palestinians have “a culture indivisible from their surroundings, a language of freedom concordant to the beauty of the land.” (He also celebrated October 7 as “the Palestinian resistance in Gaza launch[ing] a remarkable offensive, unprecedented in its scope and design,” before engaging in rape denialism.) Jamal Nabulsi, who won the 2024 British International Studies Association Colonial, Postcolonial, and Decolonial Paper Prize, explains that “Palestinian Indigenous sovereignty is in and of the land. It is grounded in an embodied connection to Palestine and articulated in Palestinian ways of being, knowing, and resisting on and for this land.” (On October 7, 2023, Nabulsi tweeted: “There is no purity in resistance. But there is always purpose. Free Palestine, from the river to the sea.” His account is now private.)

As to the competing claim that the Jews are the rightful sovereigns, these fanatics can muster essentially no response. One key settler-colonial theorist insisted on his book having separate chapters about Jewish history in the Middle East specifically to “emphasize discontinuity,” because an honest history “would reproduce a crucial tenet of Zionist ideology.” The ideology of settler colonialism thus drags its supposed factual underpinnings around by the nose. Theorist-to-the-stars Rashid Khalidi of Columbia University writes in The Hundred Years’ War on Palestine that “establishing the colonial nature of the conflict has proven exceedingly hard given the biblical dimension of Zionism, which casts the new arrivals as indigenous and as the historic proprietors of the land they colonized.” Is this dimension wrong? Khalidi maintains plausible deniability by calling the Jewish connection to the land an “epic myth,” playing on the vagueness of those words to suggest that either the Jews are lying about who they are, or that Westerners are smitten with a story of biblical proportions. Never mind that the Jewish connection to the land in the post-biblical era is also well-established; the important part is to downplay the importance of facts altogether in favor of something less tangible that can ennoble anti-Israel savagery.

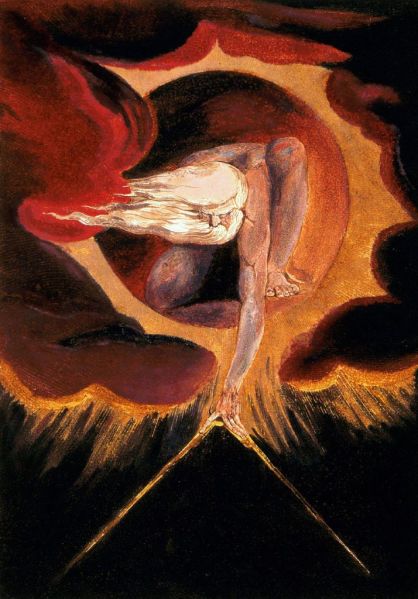

Kirsch summarizes this line of “reasoning” perfectly. It is distinct in “its irrationalism … the idea that different peoples have incommensurable ways of being and knowing, rooted in their relationship to a particular landscape, comes out of German Romantic nationalism.” That idea naturally led to the blood-and-soil ideology of Nazism, which deplored Jewish “contamination” of otherwise “pure” Germanic realms like music and science. The Nazis destroyed the gravesites of Jewish musicians whose popular work defied “indigenous” structures and forms, and derided Albert Einstein’s theory of relativity as “Jewish science.”

Today’s settler-colonial theorists may not be drawing on Nazi ideas about Jewish defilement of pure indigenous “ways of being”—though they are surely influenced by Karl Marx’s revulsion at the Judaized economy of barter and free exchange—but the two schools of thought share what Max Weber called an “elective affinity.” That is, they are two strands of thought that have certain core “insights” in common and become mutually reinforcing. Salaita certainly sounds a Streicherian note when he writes, as quoted by Kirsch, that for Zionists and their “ruthless schema, land is neither pleasure nor sustenance. It is a commodity … Having been anointed Jewish, the land ceases to be dynamic. It is an ideological fabrication with fixed characteristics.”

This doesn’t make sense and isn’t supposed to. It is not an attempt at a rational argument. It is a peculiar combination of pseudo-psychology, spiritualist incantations, and multisyllabic words plucked seemingly at random. It is not designed to advance anyone’s understanding of the world. It is designed instead to intimidate the college students who will be assigned Salaita’s book in their Middle Eastern Studies courses to get with the program.

Kirsch, to his credit, lets readers draw their own conclusions about what might be motivating the settler-colonial theorists’ kampf against a nation that doesn’t even fit their claimed paradigm. He spends a significant amount of time grappling with another pressing question raised by the theorists’ rising influence among activists. What do they want? It’s clear that they want the Jews of Israel expelled, killed, or serving as dhimmi in an Arab state in the Levant. Subjugating a few million Jews is, relatively speaking, within reach. But as to the rest of the colonies they consider ontologically genocidal—primarily the U.S., Australia, and Canada—what endgame do they have in mind for the hundreds of millions of citizens they call settlers?

Kirsch’s answer serves as a valuable criticism of the theory, but one that undersells its adherents’ unhinged barbarism. He proposes that settler-colonialist believers have no endgame in mind, because they cannot kill and expel everyone in the West. They instead fixate on tearing down every artifact of a past defined by exploitation. We have certainly seen this tendency play out concerning language, icons, historical narratives, and so much more in recent years. Even land acknowledgments—one seemingly benign introduction to this malign ideology—suggest that there is hope in returning to Year Zero if we simply pretend the last half-millennium was an aberration. Kirsch suggests, accordingly, that what these ideologues want is violence, directed wherever they can bloodlet, like a depressed individual who cuts himself and hurts others because he feels unworthy of comfort in a broken world.

It is hard to disagree with that, except to say that it is an understatement. The sheer inhumanity of the throngs of Westerners boasting their support for the Arab Einsatzgruppen that terrorized the Gaza Envelope, students of Khalidi, Salaita, and the rest of the charlatans, tells a more ominous story. They believe, like the Nazis before them, that they have unlocked the key to a properly ordered world based on a set of crazy ideas about which groups are innocent and which are guilty of everything. And like all Marxists, they want to play God. But they want to play Him in the Noah story, not in the tale of the creation of man, which imbues in us the image of the divine. They want to destroy the world, because they think it is corrupted beyond all measure.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.