With just days until his inauguration, it would not be a shock to learn that Donald Trump is walking around Mar-a-Lago singing Starship’s No. 1 hit song from 1987 (the same year he published The Art of the Deal): “Nothing’s Gonna Stop Us Now.”

Confirmation hearings for Cabinet-level posts are moving right along, with Republican senators getting in line. The transition from the Biden administration to Trump’s has been relatively smooth. Politically, Trump has never been more popular. It’s a period of such good feelings that even (some) Democrats are playing nice with Trump.

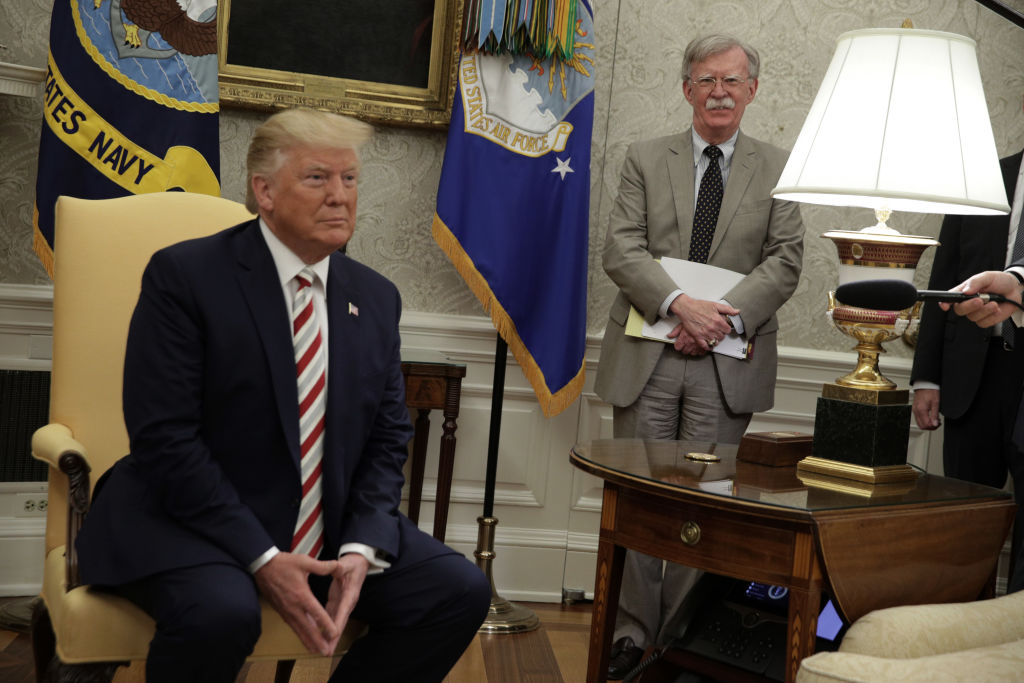

“Everybody’s optimistic. Everything seems possible. No limits appear,” says executive branch veteran John Bolton. “It lasts right up until noon on the 20th, when reality strikes.”

Up to now, the focus of most commentary and reporting has been how the second Trump administration will reshape the country and the world: the national economy, the country’s global standing, both the operation of government and everyday life in the nation’s capital, the trajectory of American politics, Congress, big business, and even popular culture.

But as it has in past administrations, the world itself has the ability to stop a presidency dead in its tracks. So how should an incoming Trump official think about the incredible, and most likely incredibly frustrating, challenges to come?

On Monday the work of the second Trump administration will begin in earnest, starting with the more than 100 executive orders promised by his transition. There will still be plenty of confirmations to go through, not just for Cabinet secretaries and prominent agency heads, but many of the lower-level but still Senate-confirmed positions Trump will need to fill. The process for accomplishing his legislative agenda remains a mystery to his allies in Congress. Nor do the Republican Party’s margins in both houses of Congress leave much room for error. And the looming midterm elections of 2026 will start the clock on how much real time this already-lame duck president has to get it all done before a potential shift in power in Washington.

On top of all that are what Donald Rumsfeld called the known and unknown unknowns that can throw a presidency off its plan: natural disasters, terrorist attacks, international incidents, economic calamities. Trump had direct experience with this in the form of the COVID outbreak in 2020. A development in Ukraine or a provocation from China could complicate whatever domestic plans the Trump administration has. So, too, could injunctions and lawsuits in response to his executive actions.

So while Trump is now an old hand at being president, the real work of governing falls to the thousands of appointees, advisers, and staff of the executive branch. That, says Bolton, is where the real action—and real obstacles—will appear.

“When it comes to the running of departments and agencies, day by day, a lot depends on the deputy secretary, the undersecretaries, the assistant secretaries, and those we still don’t know a bunch about. So in that sense, the transition continues, except it continues under the gun, [when] you’re making policy, making decisions that every day that have real world consequences,” Bolton says.

And he would know. The 76-year-old attorney has served in every Republican administration since Ronald Reagan’s, including multiple positions in both the Justice and State departments. From perches that run the gamut from mid-level agency administrator to Trump’s national security adviser from 2018 to 2019, Bolton has seen administrations struggle with the responsibilities of governance from multiple vantage points. It’s hard to live up to the promises of a campaign, no matter how unified your party is or how poorly your predecessor performed.

And beyond the base level of difficulty in running a massive government bureaucracy, implementing policy, and spending political capital effectively, carrying out the business of a Trump administration is uniquely demanding. It requires officials and staff to be prepared for the whiplash of contradictory directives or sudden decisionmaking from a capricious chief executive, who, as Bolton recently wrote for the New York Times, expects loyalty to himself above all. Bolton’s advice to those coming in to work for the administration? Be prepared for all of that.

“People who have been in the government before have seen how presidents have operated who are disciplined,” Bolton says. “George H.W. Bush being perhaps the most disciplined, but Reagan had a certain discipline. George W. Bush had a certain discipline. Trump doesn’t have a discipline, and that is hard just in the regular course of trying to decide policy.”

Like many who worked for Trump during his first presidential tenure, Bolton has been vocal about how tumultuous the work can be. But for those who will be navigating what he calls the “continuing turmoil” of advising Trump, Bolton has some straightforward recommendations.

“If you’re a senior official, White House staff, Cabinet officer, whatever it might be, your job is to present to the president the information that he should have to make a decision. Present the options, get a decision, and then carry it out,” he says. “And you can’t be held responsible if he doesn’t care about the information you’re providing or doesn’t want to look at options, that’s still what you should do, because that’s what serves the country.”

Sometimes the best policy could be keeping your head down, particularly if your corner of the government doesn’t often grab Trump’s eye. “In many departments and agencies, you know, if, once they get over there and begin to do the things they think that almost any Republican administration would do if Trump doesn’t pay any attention to them, that could well be a blessing, because they could get a lot more done that way,” Bolton says.

And knowing when to call it quits, too, is just as important. “When the time comes that your principles are being violated or you just don’t think he’s paying any attention to you, that’s the time to get out,” Bolton says. “And you shouldn’t regret that, because you know this job is temporary going in, and as long as you know it could end tomorrow, you sleep a lot better at night and you perform better on the job.”

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.