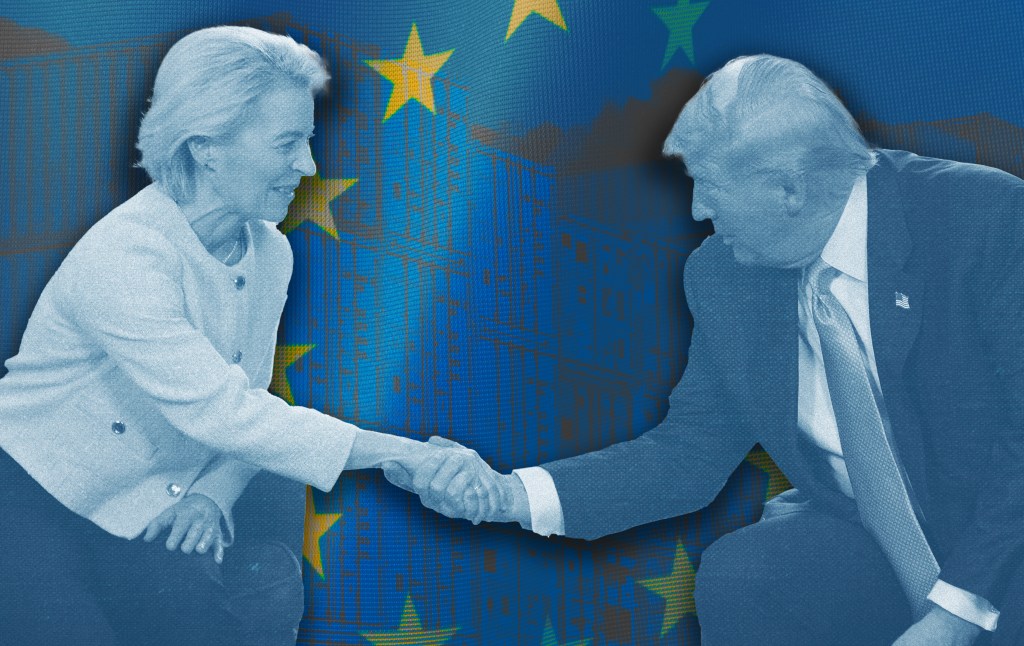

Since the news broke that European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen and President Donald Trump agreed to framework for a trade deal, the general reception has been that von der Leyen caved and that Trump got everything he wanted: The EU will face 15 percent tariffs, while American exports to the EU will face zero. Despite appearances, the reality is that Donald Trump got played.

First, we need to understand that what von der Leyen has signed is not a trade agreement, but a framework. The European Commission president does not have, and never has had, the authority to sign a trade agreement. Von der Leyen can only initiate the process of reaching a trade agreement, starting with a framework, which is what they agreed to.

That is only the beginning of a long and convoluted process. First, the European Commission must approve it. That’s the easy part. Then it goes to the Council of the European Union, and that’s where things get interesting—or difficult, rather. The Council is roughly equivalent to the U.S. Senate, in that each member state has one vote regardless of size. For a trade agreement to pass, it typically needs a 55 percent majority—15 out of 27 states, and those 15 states must represent at least 65 percent of the Union’s population.

But that is not the only hurdle, nor the biggest: The framework as agreed upon almost certainly qualifies as a “mixed agreement.” Such deals must pass the Council unanimously, and must also be approved by each member state’s national parliament. Under the treaties that govern the EU, there are certain matters in which the EU holds all the power and member states cannot do anything without EU permission (such as agricultural subsidies and trade agreements). Some political matters (such as taxation, criminal law, education, and food) are left to member states. And some—most—policy areas have a mixture of both. Any deal that involves policy areas that are not the exclusive domain of the European Union is a “mixed agreement” requiring unanimity.

Even if a deal were to gain unanimous support, the European Parliament will also want to have a say, and this is a parliament that is not scared of dragging out a process to extract its pound of flesh. The Court of Justice of the European Union could also interfere, causing further delays.

Reaction to the trade deal indicates that von der Leyen would struggle to whip all the countries (or even 15 of them) and a majority of the European Parliament. France’s prime minister described it as “submission,” and German Chancellor Friedrich Merz said tariffs would impose a “serious burden” on his country’s economy (though he grudgingly acknowledged that “more simply wasn’t achievable”). Hungary’s Viktor Orbán complained that, “It was Donald Trump eating Ursula von der Leyen for breakfast.”

Why, then, did she agree to this framework? By promising that the Union would buy $750 billion worth of U.S. energy, invest $600 billion in the U.S., remove digital trade barriers and change food sanitation rules to allow the U.S. to export pork and dairy to the EU, von der Leyen ensured that the deal would be a “mixed agreement” requiring unanimity to pass.

Before the framework was agreed to, the European Union faced the prospect of 30 percent tariffs starting on August 1. Even if the framework, or rather a deal that aligns with the framework, were to pass, it would take a long time. Each parliament would have to debate and vote, and the Council would have to meet and meet again, as would the European Parliament. The fastest trade agreement ever passed by the EU was the one it reached with the United Kingdom after Brexit, which took a mere 10 months. Durations of three to five years are more typical, even when the agreements are highly favorable for the EU.

What Ursula von der Leyen did was buy the EU time.

Von der Leyen and the EU are counting on Donald Trump’s star to fade. The 15 percent tariffs kick in today, and American consumers will be paying the price. While the Federal Reserve has been able to keep inflation at a reasonable level despite the tariffs, close examination of the affected goods show that prices are indeed rising. Everything suggests that they will continue to do so as supplies manufacturers bought to guard against the “Liberation Day” tariffs run out. And the 2026 midterms also may diminish Trump’s political leverage if the GOP loses seats in Congress.

Of course, Donald Trump could tell the EU to hurry up and pass the deal, or the 30 percent tariffs are back on. Yet, as the already-existing tariffs begin to bite, such a threat will become only less credible. And again, von der Leyen simply does not have the power to fast-track this process, as she will be sure to remind Trump.

Making matters worse for Trump, the framework is vague in ways that solely benefit the European Union. As mentioned earlier, according to the White House, the EU has agreed to invest $600 billion in the United States, buy $750 billion worth of energy, remove digital trade barriers, and deregulate food sanitation rules.

The problem is that none of these things are in the framework. Rather, the framework speaks only of the “intention” of the EU to do certain things, or an “expectation” of certain actions, and “improving access” for certain U.S. exports. Some areas, like food sanitation and digital trade barriers, are not mentioned at all in the framework, contrary to what the White House claims. They were no doubt discussed, but they did not make it into the final document.

If and when Donald Trump complains to Ursula von der Leyen that ratification is taking too long, von der Leyen may counterthat, if it were not for these provisions on investing in America and buying American energy, the agreement may pass faster, as these are among the most controversial provisions and also ensure the deal is a “mixed agreement.” This would put Trump in a tough spot, since he has already promised a deluge of European investment into America.

Alternatively, von der Leyen could point out to Trump that these provisions aren’t technically binding, but she is of course very happy to push for the EU to accept binding terms, if Trump is willing to lower the tariff rate a smidge and exempt a few more industries from them. And if Trump wants to keep his promise to American farmers that they will be allowed to export meat into the massive EU single market, von der Leyen is of course willing to push for deregulation, even though it’s not even in the framework … in exchange for another few exemptions. The barriers to digital trade that are so important to some of Trump’s supporters in Silicon Valley can also be on the table, in exchange for more exemptions.

Why would von der Leyen take this tack rather than retaliate with countertariffs? Just as it is difficult for the EU to rapidly approve a trade deal, it is almost equally difficult to rapidly approve counter-tariffs and other retaliatory measures, and the 27 member states will not be unanimous on a trade war: Some import a lot from the U.S.; others export a lot to the U.S.; and some barely trade with the U.S. at all. There was never any way for the EU to agree on a set of retaliatory measures by August 1. Thus, Ursula von der Leyen had one job: to buy time, to allow for political bargaining to take place to hammer out the details of a package of countermeasures. And buy time she did.

You do not have to share Ursula von der Leyen’s political beliefs, to appreciate that she is one of the smartest, and coldest, political players on this continent. In little over five years, she has gone from a little-known minister of defense to becoming one of only four EU presidents to be reelected in the history of the union. This did not happen by accident.

Von der Leyen does not mind being the subject of nasty headlines suggesting she has capitulated to Donald Trump; unlike Trump, she is not directly elected by the people, and the next election she needs to worry about—the European Parliament election of 2029—is four years away. She knows that whatever deal emerges, if one does at all, will be very different from the framework. She knows that Trump craves any appearance of “winning,” and would happily accept the appearance of a win against her and her ragtag band of “europoors” without looking into the fine print.

What, then, is the most likely outcome? If there is indeed a deal, it will almost certainly be a “swiss cheese” kind of deal: full of holes. Trump can save face with the 15 percent tariff rate, but the exemptions will be so far-reaching as to render this base rate virtually meaningless, and in the end, the EU may even get something reasonably close to what it originally proposed at the start of this dispute: Zero-for-zero tariffs. That would truly be the best outcome for everyone involved.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.