The Dispatch is proud to provide educators, clergy, retirees, military veterans, and students discounted access to our journalism. Check out the list and apply here if one of these categories applies to you.

There was a time when you could open the latest issue of National Review or, especially, The New Criterion and have a very good chance of seeing a serious, literate, and often enough vicious takedown of some trendy French academic or intellectual fad sweeping the English departments and the journals: Michel Foucault, of course, and Jacques Derrida, the epigones of Jacques Lacan, the ghost of Roland Barthes, Jean Baudrillard, post-structuralism, deconstruction, with most of that dog’s-breakfast being lumped together (accurately or not) under the heading “postmodernism.” This was less an idea than a creed: that there is no truth, no single authoritative account of anything—not in literary interpretation or art criticism, not in language itself, not in science or history or economics, and certainly not in journalism or anything else associated with mass media.

(The antidemocratic attitude toward mass media was one of High Postmodernism’s few redeeming qualities.)

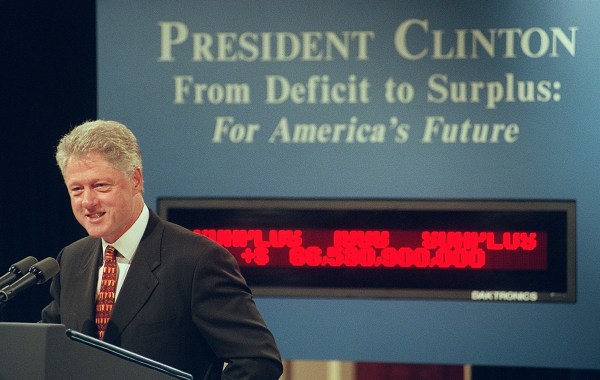

The contempt for these ideas on the intellectual right at the time was intense, and, in spite of these notions having worked up a good head of steam from the 1970s through the early 1990s, they petered out toward the end of the 20th century, not because of the many admirable vivisections of the ideas and their authors’ reputations by conservative intellectuals, but because the economic boom of the Clinton years and the technological revolution that began in earnest in early 1995 (Netscape Navigator, the first commercial web browser, was released in mid-December 1994) transformed the culture in a way that left these sour, paranoid, anti-capitalist notions poorly fitted to the demands of the time. It is very difficult to be a celebrity (and Foucault et al. were celebrities first and foremost, not philosophers) and be out of step with the spirit of the time. Brooding, Gauloises-smoking linguists were out, and billionaire techno-utopians who wanted to talk about yoga and mindfulness were in. Members of both political parties talked seriously about recruiting Bill Gates to run for president, with a bipartisan solicitousness that had not been enjoyed by an American public figure since Dwight Eisenhower. There was a degree of clarity and consensus and a mood that was libertarian and, at times, libertine: Nobody except a few contemptible and comical crackpots thought the ayatollahs had a point and that Salman Rushdie (who came out of hiding to appear on stage with U2 in 1993) should have avoided giving offense to the fanatics in Tehran, professional moral scolds such as Tipper Gore were scoffed at as embarrassing reminders of Reagan-era moral hysteria, “Just Say No” went out of fashion, Americans were following the stock market like sports scores, and the few Marxists still wandering around on the campuses were regarded as something like those Japanese soldiers still defending remote Pacific islands in the 1950s, either not having heard that the war was over or refusing to accept their loss. It was, indeed, a glorious time, and the big ideas of postmodernism were kind of crammed into an intellectual Tupperware dish and stuffed into the back of a fridge in a faculty lounge somewhere, forgotten, moldering and festering and putrefying until a few unhappy souls—including more than a few of those old right-wing intellectuals!—discovered the ghastly mess and decided to start serving it up.

As a non-paying reader, you are receiving a truncated version of Wanderland. You can read Kevin’s full newsletter by becoming a member here.

In a terrific 1989 New Criterion essay on Baudrillard, Richard Vine catalogued what he called the “seven commandments of contemporary social analysis.” These were meant as an indictment of postmodernism’s radical relativism, its intellectual flabbiness, and its fundamentally conspiratorial style. But with only a few minor emendations, one could apply them productively to the Trump-and-Twitter-era right, with its “do your own research” nonsense, its contempt for expertise and factual consensus, its rejection of historical and scientific truth, and its paranoid, thoroughly Foucaultian insistence that the media and “elites” are in cahoots in creating a “narrative,” the purpose of which is not to provide information or perspective but to control community life—politically, intellectually, morally, medically, economically—through a variety of schemes and techniques designed to exclude the hidden truth apparently known only by junkie crackpots like Robert F. Kennedy Jr. and a few game show entrepreneurs and cable television hosts.

Vine’s commandments include: “Disdain quantitative measures and hard evidence. Spin elaborate theories out of a few anecdotes,” advice taken to heart by everyone from Tucker Carlson to Victor Davis Hanson. “Sensationalize your language. When in doubt, be murky. When stating the ludicrous, be melodramatic,” i.e., do your best interpretation of Donald Trump himself. “Dissociate yourself from conventional life, capitalism, and the vulgar bourgeoisie, preferably by discovering in the unlikeliest places half-hidden machinations of repressive control,” like J. D. Vance, Marjorie Taylor Greene, or that Liver King guy. “Purport to extend and correct the prevailing vanguard position,” which is Steve Bannon’s apparent mission in life. “Systematically invert—or ‘transvalue’—all major tenets comprising the dominant doctrine of the previous generation,” which is Sohrab Ahmari’s business model. “Find inventive new applications for some standard postulates from today’s master disciplines,” anthropology and structural linguistics when Vine was writing, but evolutionary psychology, pop economics, and bro science today.

Who knew postmodernism would turn out to be so right-wing?

And what does the modern populist right demand? Only what Vine saw as the postmodernist creed all those years ago: “absolute childhood—a craven exemption from thinking, responsibility, and physical effort.”

Intellectual currents proceed in unpredictable ways. Baudrillard’s Simulacra and Simulation inspired The Matrix, which in turn provided the new (new new) right with its master metaphor, the red pill and the blue pill. But as with any ordinary stream, the easiest way to move is downhill. As Vine wrote in 1989:

Imagine, then, Monsieur Baudrillard in a restaurant. He peruses the menu fastidiously, selecting at last, with the waiter’s recommendation, medallions of veal accompanied by lightly buttered haricots verts, followed by a simple green salad, fruit and mixed cheeses, espresso, and a sliver of apricot tart—complemented by a delicate Chablis and, to finish, a noble but little known Armagnac. Then, without a quiver, and without so much as having seen any food, Baudrillard languidly calls for his check, says a gracious farewell to the maitre d’hotel, and departs, having “consumed” the signs of a satisfying repast and fulfilled all the essential requirements of symbolic exchange.

Vine’s cartoon version of the semiotician’s excesses is wry, but the absurd situation it imagines is in a way much more substantial than the reality of current political discourse: Presumably, the maitre d’hotel is a real person, whereas half of the voices on social media today are not; the restaurant is a real place, and one could, if one were inclined, at least finish off the Armagnac. Compared to reading vague moral meaning into somebody’s like of a retweet of a meme, Baudrillard’s symbolic dinner is practically Thanksgiving at Martha Stewart’s house.

Of course, we must assume that Republicans as a corporation and much of the conservative movement have fallen into the postmodernist view—that discourse is only a front for power—out of pure self-interest: Republicans have now twice elected a pathological liar (and serial adulterer, and quondam pornographer, etc.) as president of these United States, and there are a lot of people on the right whose business models and mortgage payments depend on being able to convince a critical mass of morally stunted rubes that they are doing everything in their power to defend Trump. Trump’s attacks on the notion of truth are fairly unsophisticated—the Stalinist firing of that BLS executive over insufficiently rosy employment reports, maintaining that his net worth depends on how he is feeling about himself that day, etc.—and the ladies and gentlemen who fill the role of conservative intellectuals today (and while Tucker Carlson may have for some inexplicable reason dived headlong into a bottomless well of fortified cretinism, he is Rabindranath Tagore compared to Sean Hannity, whose brainwave activity reads somewhere between that of Joe Biden and the late Hulk Hogan) barely expend any more effort cooking up intellectual pretexts for the president’s lies, his other abuses, his ignorance, and his breathtaking stupidity.

The thing about Baudrillard and the gang was that they started with a point, albeit a trivial one. The linguist Ferdinand de Saussure spun an entire, elaborate theory around the banal observation that there is no inherent connection between the sound of a word and its meaning—English speakers could have used “cat” to refer to the good kind of pet and “dog” to refer to the other kind, but they did the opposite for reasons now lost to philology. The “arbitrariness of the linguistic sign,” as the Saussureans call it, is a real thing. It just doesn’t mean very much, and it is not as though there were some great linguistic edifice based on the opposite assumption—a rose by any other name and all that. Similarly, the signs we use for numbers are more or less arbitrary (although one can trace some of them back to non-arbitrary hashmarks, i.e., the Roman numerals I, II, III, and the much older Brahmi numerals for the same, which look like the Roman ones having a nap) but math and physics still work, however arbitrary the signs used in E = mc2. Likewise, conservative complaints about things such as media bias or double standards in social media moderation are not based on nothing—they just explain a lot less of how the world works than the people who have to follow Republicans around with an intellectual shovel and broom pretend that they do. If Donald Trump were caught on camera raping a platypus on the South Lawn tomorrow, what would Hannity say? “The biased media would never make such a big deal about raping a platypus on the South Lawn if it had been Barack Obama. And who is to say that Obama didn’t? I’m not saying Barack Hussein Obama did that. I’m just asking questions. Do your own research.”

There are, of course, gross financial factors at play. What Fox News seems to have learned from the Dominion lawsuit is that it can afford to lie to its viewers more readily than it can afford not to lie to them. But it also seems to me that a great many on the right have genuinely taken those dusty old postmodernist notions to heart—that they actually believe this baloney, that they can somehow turn the humiliating defeat of the 2020 presidential election into a resounding victory, that Trump’s actions following that defeat were not an attempted coup d’état but honest and decent actions resulting in that “patriot purge” Carlson rants about in such imbecilic fashion. You see some of this in the self-help swill from the men’s movement, i.e., the belief that pretending to be a confident, high-status man is practically speaking the same thing as being one.

Of course, a lot of this is something Jonah Goldberg talks about frequently: ideas that are trailing indicators rather than leading indicators, intellectual fig leaves and window dressing for events and social developments that came to pass before the ideas vindicating them were decocted from current events. Some of it is Christians looking for a way to exempt themselves from the rule about “bearing false witness,” as in the case of J.D. Vance and those fictitious cat-eaters in Springfield, Ohio. But there has been a real shift, of a kind, too. There are plenty of smart people who know that Trump is lying to them—a few of them work directly for the man. But people such as Vance and Trump’s top advisers have decided that the truth just doesn’t matter. Vance justified lying about black immigrants in Springfield on utilitarian grounds: “If I have to create stories so that the American media actually pays attention to the suffering of the American people, then that’s what I’m going to do,” he said.

But, having abandoned long-held principles such as limited government, free trade, the rule of law, etc., why not abandon truth, too? I cannot imagine this will be good for the intellectual and moral health of the right. But, then, the right does not seem to care very much about intellectual or moral health right now—just don’t get them started on seed oils.

And Furthermore …

It is amazing to remember how much prestige the French still had back in the 1990s—not only French intellectuals but also French politicians and French political culture. When Bill Clinton was being run through the wringer over his sexual relationship with a White House intern and the many lies and acts of obstruction he engaged in to cover it up, his critics were treated to endless dismissals that the sophisticated French would never get so worked up by the appetites of a great man. Only we puritanical Americans care about that sort of thing.

(That they thought Clinton was a great man was pretty funny, too.)

And Furtherermore …

On truth and goodness (and beauty), you might enjoy this essay by Thiago M. Silva published by the C.S. Lewis Institute.

Words about Words

Above, I wrote about baloney—the metaphorical kind, not the fried-on-a-sandwich kind. (Fried-baloney sandwiches on Mrs. Baird’s bread were a thing when I was growing up, and maybe they still are. Fried Spam sandwiches, too.) It is easy enough to see how the pronunciation of Bologna sausage, named for the Italian city that is home to the Western world’s first university (founded in 1088) might have been corrupted into baloney, but what about the meaning? How did the poor man’s mortadella end up indicating nonsense? A reader recently asked me to look into it.

The answer is, as it sometimes is: Nobody really knows. The most popular theory is that as baloney came to be known as a cheap, mass-produced lunchmeat, it was understood to be composed of disparate, sundry, and disreputable bits of this and that. (Here, the Pennsylvania Dutch scrapple is more straightforward, having the word scrap right in there.) So a claim or an idea that was based on a mess of disreputable stuff became known as baloney.

Asked why Robert F. Kennedy (the McCarthyite attorney general, not his son, the crackpot junkie HHS secretary) always refused to appear on Firing Line, William F. Buckley Jr. replied: “Why does baloney reject the grinder?” Clare Luce Booth, writing in 1943, characterized Henry Wallace’s glib internationalism as “globaloney.”

Political discourse: We have the meats.

Elsewhere

You can buy my most recent book, Big White Ghetto, here.

You can buy my other books here.

You can check out “How the World Works,” a series of interviews on work I’m doing for the Competitive Enterprise Institute, here.

In Closing

That Richard Vine essay ends with a banger:

The gimmick-mongers of contemporary French thought are guilty of many logical and factual errors, but these are as nothing compared to their fundamental moral dereliction. For their infatuation with the indeterminacy of texts, the decentralization (and denaturing) of the authorial subject, the provisional quality of every explication, etc., yields a Vichy interpretation of literature—wishfully proposing a world in which no particular individual is responsible for any particular act, in which the capitalist system ruins lives day and night, while no upstanding leftist intellectual, whatever his views, could possibly be accused of complicity in the slaughters of the Khmer Rouge or the admissions policies of Soviet psychiatric hospitals.

For twenty years now we have suffered the ascendancy of the congenitally evasive. They have taught us their fear of social virility, their horror of virtù.

The horror of virtù remains very much with us. It is strange how excessive admiration for the will to power brings out the servility in so many men.

Correction, Aug. 11, 2025: This article has been updated to correct that the person who described Henry Wallace’s internationalism as “globaloney,” in 1943 was Clare Boothe Luce, not Clare Luce Booth.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.