When students settled in to a sociology class on the University of Wisconsin-Madison campus on September 14, 2018, the professor started describing certain theories he said he was eager to critique in a proposal that he was thinking of sending to the sociology department.

Yet, the professor added, some theories and beliefs couldn’t be critiqued; he called them “sacred cows” within academia.

This statement angered one student, who complained to university administrators that use of the term “sacred cows” was inappropriate.

“The way he used this term was offensive to me, because in some cultures, cows are deemed to be sacred, and his employment of the term as a snarky rhetorical device demonstrates the lack of awareness or concern this person has towards future colleagues and students who might be from those countries,” the student wrote.

“I grew up in India, and found his use of this terminology to be condescending and racist,” the student added. “I would not feel safe around him, and feel that his confident lack of awareness perpetuates the unsafe white-centric and white-supremacist environment of UW-Madison.”

The student filed this complaint using the university’s “Bias or Hate” reporting website, which encourages campus community members to report any uncomfortable interaction they encounter on campus. Students may file behavior reports anonymously against other students for words uttered in private interactions, or may report professors for words said in front of a classroom. The site began taking reports at the school in 2016, at a cost of $60,000 per year.

During the 2018-19 school year, 107 bias and hate complaints were filed at UW-Madison, each of which I retrieved through a freedom of information request. While the information identifying students and professors was redacted, the breadth and scope of what campus community members are willing to report one another for is revealing.

UW-Madison isn’t alone—In 2017, the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education found 232 American schools with Bias Response Teams. This number is almost certainly outdated—in 2020, it is difficult to find any major public university that doesn’t have some sort of reporting structure, whether they call it a campus “climate,” “bias,” or “caring” system. And with students defining themselves both by their group affiliations and victim status, such structures allow them to portray their campuses as snakepits of hate and vituperation, where discrimination runs rampant.

The UW-Madison website itself offers an unwieldy, broad definition of “bias” incidents that should be reported to administrators.

“Bias,” according to the school, comprises “Single or multiple acts toward an individual, group, or their property that are so severe, pervasive, and objectively offensive that they create an unreasonably intimidating, hostile, or offensive work, learning, or program environment, and that one could reasonably conclude are based upon actual or perceived age, race, color, creed, religion, gender identity or expression, ethnicity, national origin, disability, veteran status, sexual orientation, political affiliation, marital status, spirituality, cultural, socio-economic status, or any combination of these or other related factors.”

Of course, such a system lets individual students decide what violates their own feelings of propriety.

In some ways, Bias Response Teams are more stifling than the pernicious campus speech codes of the 1980s—they turn classrooms, dorms, and student unions into surveillance states, where thoughts expressed in private conversations can make their way into the hands of a university diversity administrator. The university is effectively imposing a nebulous speech code, then crowdsourcing its enforcement. In fact, at the UW-Madison, the campus Bias Response Advisory Board includes two members of the UW Police Department —making the board a literal “speech police.”

“Our campus is home to students from a wide variety of backgrounds, identities and points of view—that provides opportunities for learning but also, sometimes, for misunderstanding and conflict,” UW-Madison spokeswoman Meredith McGlone told me. “The bias response system is a resource for all students to talk through challenging situations they may encounter.”

On September 4, 2018, a UW-Madison student was watching video of an online course being taken by her roommate. On the video, a professor was making the case that it is often difficult for students with disabilities to understand and process information—to hammer this point home, the professor began speaking “in a way that mimics those with differing mental abilities,” according to the student.

“At first, my roommate believed this was how he was actually going to lecture, then, a pair of puppets are shown in the video describing how terrible this professor would be as a lecturer,” the student reported. “He says, ‘Oh no, this is terrible’ and ‘this is going to be awful’ or ‘can you imagine a whole semester with this guy?’”

“We were extremely offended as my roommate herself has a speech impediment, but also for any person living with a disability,” the student added, writing the video “far surpasses the border of what is appropriate.”

“The slowed speech, gestures he uses, and the fact that he later shows the contrast between what he presented and how he will actually present himself led me to believe this wasn’t just a joke gone too far.”

Also in September 2018, a student reported a flyer distributed by the school’s Morgridge Center encouraging students to vote. The flyer for the “Big Ten Voting Challenge,” in which the conference’s schools compete for the highest Election Day turnout, featured a photo from a Wisconsin Badgers football game in which all the students are holding their arms forward and above their heads.

“It shows students for voting materials very nazi / hate group vibe,” the student reported.

On September 27, an adviser for the Multicultural Learning Community Floor in a campus dorm noticed that some construction paper decorations taped to the office’s front door had been rearranged in the shape of a penis.

“As a mentor, it is my responsibility to help the residents when they come across life’s challenges,” the advisor reported. “Up until last night, there was no physical evidence of vandalism, microaggression, or racism. However, now there is. … This is not okay.”

At the end of a class in October, a student asked a professor to acknowledge that it was Indigenous People’s Day. The professor answered that it wasn’t necessary because the class would be discussing the topic the following Thursday.

This answer was unsatisfactory for the student, who sarcastically noted, “As if our progression only exists in academic settings, and is not to be acknowledged when it is actually happening in real life.”

“This class as a whole has been one of the only things preventing me from feeling fully mentally healthy because of the nature of the class and the lack of indigenous representation,” the student reported.

“Native students are silenced by white professors and TAs in this American Indian Studies Department, and this is not addressed, especially because the Director of the program is a white anthropologist. … These classrooms are not safe spaces for indigenous students.”

In reading more than 1,000 bias complaints from over 20 public colleges in the past year, I found complaints about professors to be one of the most frequent reports filed. Typically, a student will hear something from a professor with which they disagree, then report them for failing to offer a trigger warning when discussing sexual assault, for engaging in transphobia for mixing up a student’s pronouns, or for making comments the student deems to be racially insensitive.

At some universities, professors who are on the receiving end of these complaints are never notified there has been a report filed against them. Sometimes when a complaint is lodged, a public record is created of their transgression, which can lead to a letter being added to their file. These notations can hurt professors either seeking tenure or looking for jobs at more prestigious universities. Often, there is no appeal process, with the professors unable to tell their side of the story.

Advocates for bias teams argue the systems often have no investigative or enforcement mechanisms. In an article for Inside Higher Education last June, pro-bias response researchers wrote that BRTs “do not shut down free speech or charge into classrooms to stop offensive statements from faculty members or students.”

But in many cases, bias teams do investigate alleged “hate” speech. A controversial statement at dinner with a fellow student can earn an undergraduate a visit from a diversity counselor. Students have been called to testify in front of panels or have been forced to attend diversity workshops for things they’ve said on campus. Complaints are recorded in public files that can be permanent.

All of this has the effect of chilling speech on campus, as students who are anti-abortion, support traditional marriage, or argue in favor of stricter immigration policy can find themselves reported to the administration for making campus “unsafe.” Rather than being pulled before a diversity counselor, students are better off simply keeping quiet if their views do not comport to the day’s accepted progressive canon.

These tools can also leave instructors in a nearly impossible position. In November 2018, at a Zumba class at UW-Madison, a female student left her place during the workout and sat down. When the instructor asked her what was wrong, she said she was too hot—so the instructor turned on a large fan at the front of the class.

This, however, made several of the women at the front of the class too cold, so they went to turn the fan off. The instructor yelled at them for doing so, which brought charges of racism.

“The fact that that one girl who was not feeling well was White, and that the three of us were Asian, has led me to think uneasily about whether the incident came from racism and made me uneasy,” a student wrote in a complaint against the instructor.

“Even if it was not about race, what [name redacted] did was neither appropriate nor professional, for she had failed to pay equal attention to all her students, some of whom was White and the rest Asian.”

Later that month, a female professor was teaching students a historical political example of a U.S. senator wanting to hinder the progress of people of color. The professor referred to a 1981 case in which a senator used the “n-word,” saying the specific word out loud.

“She did not at any point address the impact of this word or the negativity of it or that she even said it,” a student complained. “It was not necessary to read this word and it was not to make a point about the word at all,” wrote the student, adding that it came off “as extremely offensive.”

“This does not create a safe environment for ANY student and does NOT represent UW,” a different student complained in a separate report made the same day. “If this instructor gets away with this then who knows what happens next? Death threats to students?”

And sometimes students are merely offended by a professor’s opinion being different from theirs. For example, a nursing professor was reported for expressing a sentiment “that it was ‘refreshing’ to see a different political group (Republican majority) as the majority when students’ [sic] presented political demographic statistics of a zip code.”

“Although, this may seem like a simple comment and observation, this causes concern due to the current political climate and the policy initiatives of the Republican party,” the student complained.

The student alleged the professor “creates a negative space to allow microaggressions and is a strong example of white fragility.”

In December, a male professor was giving a lecture on policing. “Throughout the lecture I felt as though he was constantly giving policemen and woman in many cases of police brutality the benefit of the doubt,” complained a student. “I feel as though his teaching style toward this specific lecture was very bias [sic] and hurtful.”

“Personally, I feel as though he has regard for what other people have to say, but concerned about whether his opinion is right and justified,” the student said.

Pushback against bias response teams has come most notably in the form of lawsuits filed by Speech First, a pro-free speech nonprofit organization that has gone to court a total of four times in the past two years in an effort to dismantle bias reporting systems.

In October 2019, the University of Michigan settled with Speech First, disbanding its “Bias Response Team” and eliminating penalties the BRT could previously administer for speech violations. Before the Speech First lawsuit, the Michigan speech code prohibited “harassment” and “bullying,” and further increased the potential penalties if such actions were motivated by “bias.” Under this code, a student could be subject to significant penalties, up to and including expulsion, if another student perceives their speech as “demeaning” or “bothersome.”

“The most important indication of bias is your own feelings,” read the school’s website.

Per the settlement, the University of Michigan has instead replaced its Bias Response Team with a “Campus Climate Support” program that does not contact the subjects of complaints, only reporting parties.

Speech First has also filed lawsuits against bias teams at the University of Illinois, the University of Texas at Austin, and most recently at Iowa State University. All three of these lawsuits are ongoing. Each of the lawsuits argue that incentivizing students to inform on one another constitutes prior restraint on political speech that would otherwise be protected by the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution.

“The primary purpose of our bias response system is not to investigate or punish but to provide support and promote educational conversations,” Meredith McGlone, the UW-Madison spokeswoman, told me. “That is consistent with First Amendment protections.”

McGlone argued Wisconsin’s bias response system is different than Michigan’s in that reports are handled by a professional staff member. She noted Wisconsin also has an advisory group that meets monthly to “discuss recent reports and broader issues and concerns.”

“Our campus is home to students from a wide variety of backgrounds, identities and points of view—that provides opportunities for learning but also, sometimes, for misunderstanding and conflict,” McGlone told me. “The bias response system is a resource for all students to talk through challenging situations they may encounter,” she said.

In February, McGlone herself reported an incident to the Bias Response website. According to McGlone’s report, some teenage boys visiting Madison for the state’s high school championship wrestling tournament cat-called some college-aged women walking down the street. McGlone saw the women discussing the incident on Facebook and submitted their posts to school administrators.

“I am reporting this with the hope that campus officials will share this information with WIAA (the governing board for high school sports) and participating schools, make them aware this behavior is not acceptable and request that they specifically address appropriate conduct with tournament participants in future years,” McGlone wrote in her complaint.

Accompanying her report, McGlone attached screen shots of the discussion, in which one student said someone yelled “nice ass” at her. Another punctuated a post with a laughing emoji. McGlone said she was not aware of whether any of the female students was contacted before sending their discussion to the bias team.

“Just like any staff member, I have an obligation to respond when I become aware of discrimination affecting students,” McGlone told me. “The university passed along their concerns to WIAA and WIAA was very responsive. I don’t know whether any of the female students were contacted directly.”

In January, a class took a field trip during which a tour guide read from a historical text that referred to Native Americans as “savages.”

After the field trip concluded a report was filed, noting “The professor did not intervene or clarify afterwards that native people are not savages.”

“This incident communicated to me that a huge leader in the field thinks it is ok to call native people this demeaning slur,” the report read.

Also in January, a student reported a botany professor for “dead-naming” transgender scientist Joan Roughgarden, mistakenly introducing her using her former name “John” in a lecture slide.

Several days later, a non-student citizen named Jim Estes reported the UW Police Department for a humorous social media post featuring a police officer wearing a short sleeved shirt with the caption “#sleevesmatter.”

Estes claimed the posts were “offensive, as they are clearly making fun of #blacklivesmatter with the #sleevesmatter reference.” He deemed the posts “not funny” and claimed “this is why they have community trust issues.”

The same day, a student filed a report against a professor who had given his students the assignment of writing a brief essay on the relationship between Maurice Ravel’s Ma Mere L’Oye Suite and a dance performance by Kansas-based youth company Ballet Midwest.

Several students took the opportunity during an in-class discussion to express concern over how various Asian cultures were depicted through the choreography.

According to the complaint filed against the professor, he “appeared to praise students who did not write about the dance’s cultural insensitivity, expressing that he was ‘glad [they] did not have a concern about the Asian motif.’”

The professor allegedly “criticized students whose essays included a discussion of how the choreography misrepresented various Asian cultures. He labeled these submissions as ‘harsh assessments.’”

If diversity measures like Bias Response Teams are meant to give students from marginalized groups a more comfortable campus experience, it doesn’t appear they have been successful. In 2017, UW-Madison released results of a “Campus Climate Survey,” in which 81 percent of students overall reported they felt “welcome” on campus.

But numbers for minority groups lagged behind those of the general population. Only 69 percent of LGBTQ students, 67 percent of students with a disability, and 65 percent of students of color felt welcome on campus. At the bottom rung were transgender and non-binary students, 50 percent of whom responded that they felt welcome on campus.

It is possible that initiatives like BRTs are actually doing more harm than good, as they force students to be on high alert for racial and gender-based transgressions at all times. Encouraging students to report one another may be institutionalizing victimhood and teaching students that the university is responsible for ensuring every utterance they hear is non-confrontational.

It is worth noting that the rising accusations of bias are taking place in the most progressive enclaves of America—prestigious college campuses. In the past two decades, both public and private universities have stuffed themselves with “climate” and “diversity” administrators, crowing to students about their dedication to equality. Yet the campuses’ fealty to diversity may be having the opposite effect—it may be convincing students discrimination is an inextricable aspect of campus life.

In 2014, sociologists Bradley Campbell and Jason Manning studied the effect so-called “microaggressions” have had on college campuses. According to Campbell and Manning, universities “increasingly lack the intimacy and cultural homogeneity that once characterized towns and suburbs, but in which organized authority and public opinion remain as powerful sanctions.”

“Under such conditions complaint to third parties has supplanted both toleration and negotiation,” Campbell and Manning argue. “People increasingly demand help from others, and advertise their oppression as evidence that they deserve respect and assistance. Thus we might call this moral culture a culture of victimhood … the moral status of the victim, at its nadir in honor cultures, has risen to new heights.”

Or, as put by Jonathan Haidt, social psychologist and co-author of The Coddling of the American Mind: How Good Intentions and Bad Ideas Are Setting Up a Generation for Failure, “victimhood culture causes a downward spiral of competitive victimhood.”

“Young people on the left and the right get sucked into its vortex of grievance,” wrote Haidt in 2015.

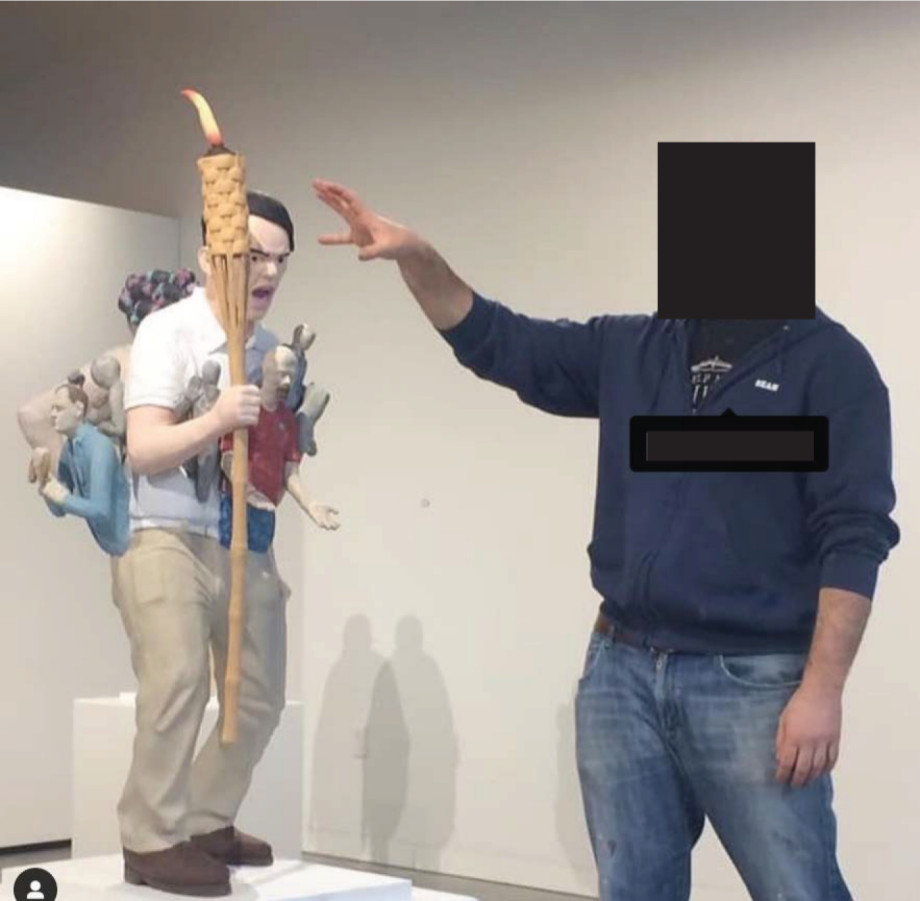

In February, a university art exhibit featured a provocative sculpture of an Alt-right protester carrying a tiki torch. The piece was titled The Root of Hate.

According to a student filing a report against the school for allowing the sculpture to be displayed, the statue featured “many other figures on it that were clearly trying to rationalize this despicable human action including a rather insensitive depiction of what could be construed as mother.”

“It was offensive to look, and brought up terrible thoughts about the rally in Charleston. It was triggering.” (Presumably the student meant “Charlottesville.”)

In April, a group of students in the same dorm took to a Facebook Messenger chat to threaten a cisgender male student who was heard saying he “would not feel comfortable sexually engaging with another male who identifies as a trans woman.”

According to screen shots of the chat, a man said he wouldn’t want to have sex with a transgender woman “because she has a penis.” The text of the chat suggests the straight, cisgender student was having a talk with a transgender individual and earnestly asking questions about transgenderism.

“At least he used the right pronouns but god kill him,” wrote one student. “I’m going to stab him with a dick shaped knife,” wrote another.

Another student reported the conversation on the threatened student’s behalf.

In May, a student complained about a Facebook advertisement for an upcoming panel discussion at the UW Department of Pediatrics that featured all white, male doctors and was subtitled “Is There a Doctor In the House?”

“There are many amazing faculty of color doing grand rounds, and the school decided to highlight this one in particular is difficult to justify considering that the title might to be considered exclusionary,” the student reported.

In 1905, former University of Wisconsin president Charles Van Hise announced the tenets of the “Wisconsin Idea,” a philosophy in support of an activist campus that benefits the entire state.

“I shall never be content until the beneficent influence of the University reaches every family of the state,” Van Hise declared.

But Van Hise’s university has now become a factory of discontent, encouraging its students to report each other to authorities in what has become a race to learned helplessness.

Van Hise no doubt believed deeply society could be made a more vibrant, creative place with the production of more scholars. But when a university subverts its marketplace of ideas to exacerbate its grievance culture, it only creates more victims.

Christian Schneider is a reporter for The College Fix and author of 1916: The Blog.

Photograph of Wisconsin campus by Mike McGinnis/Getty Images.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.