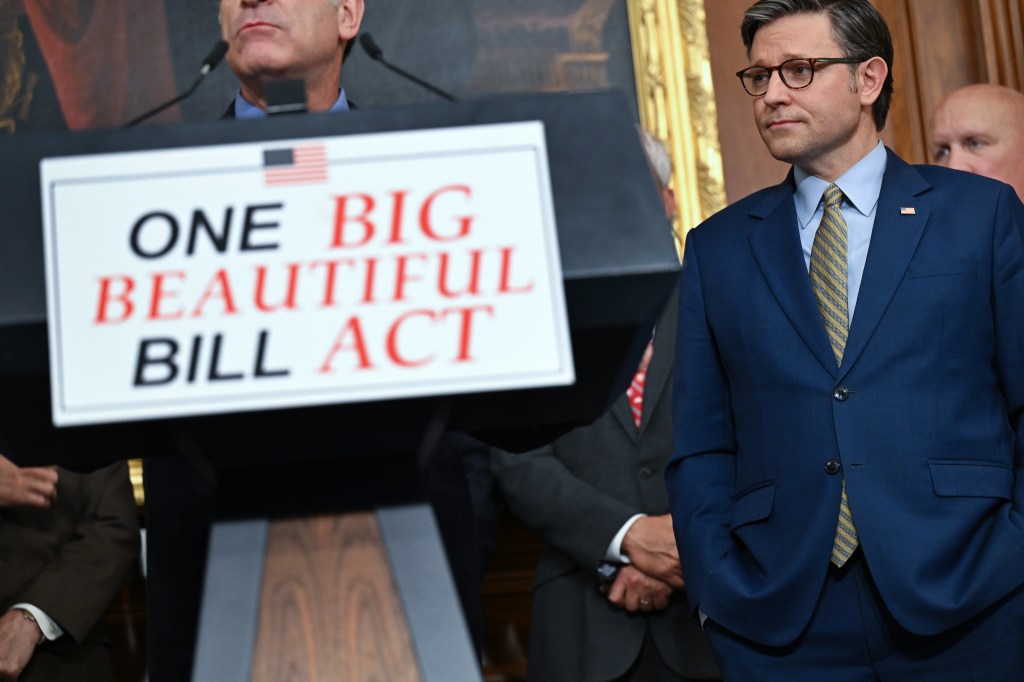

As the Senate mulls over the Trump-backed budget reconciliation bill—the One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA), which passed the House of Representatives on May 22—opponents of the legislation have voiced concerns about several provisions they say are included in the bill.

With the bill exceeding 1,000 pages, competing claims have emerged online about what the OBBBA entails. One viral graphic shared to social media warns Americans to “prepare yourself for what’s coming.” “This bill doesn’t break the law,” the graphic’s text states. “It rewrites the law so Trump never has to break it again. We don’t need to wonder what would happen if authoritarianism came to America. It’s here—in 1,100 pages, dressed up as ‘freedom.’”

The graphic states further that, if the OBBBA were to become law, it would give President Donald Trump sweeping powers, including the authority to “delay or cancel elections,” “ignore Supreme Court ruling for a year or more,” “fire government workers for political disloyalty,” and prevent judges from enforcing orders they issue, among other provisions. These claims are almost entirely false. Some of the supposed provisions mischaracterize how the law would change under the OBBBA, while others are completely unsupported by the text of the OBBBA. The bill was structured to pass Congress through the budget reconciliation process, allowing it to pass in the Senate with a simple majority vote. However, the Senate’s Byrd rule only allows changes in spending, revenue collection, and the public debt limit to pass via reconciliation.

Nonetheless, the graphic quickly gained steam on social media and other online platforms, including Facebook, Instagram, Bluesky, and Reddit. At least three separate local Democratic Party chapters—the Democratic Party of Perry County, Pennsylvania; Medina County, Ohio; and Manitowoc County, Wisconsin—also shared the graphic on their official social media account or website.

Trump ‘can delay or cancel elections’

There is nothing in the OBBBA that vests the president with the authority to “delay or cancel elections.”

In fact, the OBBBA does not make any changes to election law. The word “election” appears a total of 36 times in the text of the bill, but is used in the context of an individual or entity “electing” to make a decision. Not once does the OBBBA use the word “election” to describe an organized voting process.

Election law varies between federal and state races, as well as among the seats the election is expected to fill. For example, the Constitution states that state electors shall elect the president and vests Congress with the authority to set a date by which those electors must cast a vote for president. Through an 1845 law, Congress set a deadline for states to select their presidential electors “on the Tuesday after the first Monday in November.” Congress could always pass new legislation to change those dates, but no such changes are proposed in the OBBBA.

Even in times of national emergencies, the president has no power to “delay or cancel” elections. “Congress has enacted more than 100 statutes identifying special powers that the President may exercise during a national emergency, but none include the power to postpone or cancel any state’s chosen method of appointing presidential Electors,” Jacob D. Shelly wrote in a federal election overview from March 2020, when he was a legislative attorney at the nonpartisan Congressional Research Service.

Trump ‘can ignore Supreme Court ruling for a year or more.’

Nothing in the OBBBA grants the president power to ignore or otherwise disregard rulings from the Supreme Court for one year, or any other amount of time. The Supreme Court is not mentioned a single time in the legislation’s text.

Congress has the power to make federal law, but such authority is limited by the Constitution. Article I, Section 8, of the Constitution specifies the “powers of Congress,” and all congressional legislation must derive from at least one of these powers. If not, federal courts may strike down the law as unconstitutional. The Constitution did not give Congress the power to strip the Supreme Court of its authority through legislation.

One power vested with Congress is “to constitute Tribunals inferior to the supreme Court,” including federal district courts and circuit appeals courts. Because those courts were established via congressional legislation, they could also be disbanded through congressional legislation, unlike the Supreme Court. But no such provision is included in the OBBBA.

The Constitution, in Article III, further stipulates that “judicial power” rests with the Supreme Court. While the specific parameters of “judicial power” are not defined in the Constitution, the Supreme Court, in the landmark 1803 case Marbury v. Madison, established the principle of judicial review, thereby creating a role for a court to strike down laws it determines violate the Constitution. Ironically, were Congress to pass legislation that allows for the president to ignore Supreme Court orders, the Supreme Court could strike down that law as unconstitutional. While a constitutional amendment could revoke the Supreme Court’s judicial review power, simple congressional legislation could not.

Trump ‘can fire government workers for political disloyalty.’

There is no provision in the bill granting Trump the unilateral power to fire government employees for “political disloyalty.” Current federal law bars the government from retaliating against employees who refuse to take part in “political activity.” However, the OBBBA does include a section requiring newly hired federal workers to either 1) accept employment on an at-will basis, or 2) pay 5 percent more of their income into the Federal Employees Retirement System (FERS) than existing federal employees do.

Under this provision, Section 90002, new federal employees who choose at-will employment could be reprimanded or removed by their respective agency heads without notice or appeal for “good cause, bad cause, or no cause at all,” per the text of the bill.

The alternative for new employees would be to contribute a greater share of their salary to the FERS system. Instead of contributing 4.4 percent of pay into FERS, the standard amount that federal workers are required to contribute, new federal employees who decline the option of at-will employment will need to contribute 9.4 percent of their pay into FERS. The option to pay more into FERS does not come with increased retirement benefits. For most newly hired federal employees, the choice will be a trade-off between pay and job security. That choice is also “irrevocable,” meaning once employees are hired and make a choice, that decision cannot be changed. An April report from the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office estimated that about 75 percent of new federal employees will select at-will employment rather than contribute 5 percent more of their earnings into FERS. The bill does exempt certain federal employees from this section, including political appointees, federal law enforcement officers, and many U.S. postal workers.

Importantly, this section further states that at-will federal employees will retain federal protections currently stipulated in federal law, protecting them from being fired for actions the administration might consider “political disloyalty.” It will continue to be illegal for the government to fire employees based on race, color, religion, sex, national origin, age, disability, marital status, or political affiliation. Moreover, it would also still be illegal for the government to “coerce the political activity of any person (including the providing of any political contribution or service), or take any action against any employee or applicant for employment as a reprisal for the refusal of any person to engage in such political activity,” per existing federal law.

‘Judges can’t enforce their own laws.’

The OBBBA will not bar judges from having their rulings enforced. The premise of the claim itself is also inaccurate. Judges have no authority to create “their own laws.” The Constitution does not give law-making power to the judicial branch and vests two primary enforcement tools of the government—the power of the purse and control of the military—in the legislative and executive branches, respectively.

Courts are not powerless, however. Since the Judiciary Act of 1789, when a court determines that a party has violated a direct court order, it may issue a contempt citation against that party. Contempt is a mechanism to ensure parties are respectful to judges and comply with the court’s legal ruling. Parties held in contempt of court can face civil or criminal penalties, including fines or imprisonment.

One section of the OBBBA would limit the court’s ability to issue contempt citations for certain violations, specifically, those involving “failure to comply with an injunction or temporary restraining order.” Court cases often require extensive deliberations, and formulating legal opinions based on large swaths of legal precedent and history is often time-consuming. Preliminary injunctions and temporary restraining orders are designed to fill that short-term gap while the court deliberates on the broader legal question. If a court determines that a plaintiff has sufficiently demonstrated in their lawsuit that their legal challenge is likely to succeed, that court may issue a preliminary injunction or temporary restraining order to temporarily block the action being contested in court from continuing. Those rulings stand until the court issues its decision on the broader merits of the case.

A pre-existing federal rule, Civil Procedure 65(c), requires that courts collect a security deposit from plaintiffs prior to issuing a preliminary injunction or temporary restraining order. As the federal statute states, the courts set an amount that they determine “proper to pay the costs and damages sustained by any party found to have been wrongfully enjoined or restrained.” For example, if a plaintiff were to sue the owner of a professional baseball team over concerns that foul balls endangered fans’ safety, and a court reasons the plaintiff is likely to win on the merits, then the court may issue a preliminary injunction or temporary restraining order to prevent further baseball games from taking place, protecting fans from the potential harm posed by foul balls while the court case is ongoing. However, the court would have to estimate the amount of lost revenue the team’s owner would incur from suspending games, such as lost ticket sales, and the plaintiff would have to post a security deposit for that amount. If the plaintiff is unable to pay that amount, the court technically cannot issue a preliminary injunction or temporary restraining order.

As is not uncommon with federal law, there are exceptions to this requirement. As The Dispatch Fact Check previously wrote on Civil Procedure 65(c):

Notably, the rule states that the United States and its federal agencies are exempted from paying the security bond when they are the suing party—but that’s not the only exception. The rule states that courts ultimately decide the amount of the security bond to be posted and, in many cases—such as when the plaintiff is challenging the federal government on constitutional grounds—that amount is set at $0. The reasoning is that, if a preliminary injunction is issued, costs incurred by the federal government can often exceed millions of dollars. Security bonds of that amount would price out many individuals and organizations challenging the federal government on constitutional grounds. “The security requirement would effectively deny plaintiffs the right to challenge unconstitutional government action,” the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression’s Ronnie London said in a statement FIRE provided to The Dispatch Fact Check.

As such, there are many cases where courts effectively set no security deposit by setting that amount to $0. But under Section 70302 of the OBBBA, in cases where the court issues a preliminary injunction or temporary restraining order, and “no security was given when the injunction or order was issued,” then that court is not allowed to issue a contempt citation over a party’s “failure to comply” with the injunction or order.

If you have a claim you would like to see us fact check, please send us an email at factcheck@thedispatch.com. If you would like to suggest a correction to this piece or any other Dispatch article, please email corrections@thedispatch.com.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.