Pro-Palestinian activists are resurfacing claims that Israel subjected Ethiopian immigrants to long-term birth control shots without their knowledge or consent. The claims are more than a decade old, but social media influencers on multiple platforms have posted about them. One post from influencer Rosy Pirani, which has almost 20,000 likes as of November 7, accuses the Israelis of racism.

The Ethiopian Jewish community—known as Beta Israel—has ties to the Zionist project dating back to the 1860s. The group was formally recognized by a number of prominent rabbis in 1973 as legitimate descendants of the Israelites, making the Law of Return applicable to Ethiopian Jews.

Claims about forced contraception of those immigrants are based on actual media reports dating back to 2012, but the evidence for the veracity of the claims is mixed. Investigations into the matter were inconclusive, but also criticized for various shortcomings.

In 2012, Gal Gabai, an anchor for the news show Vacuum on Israeli Educational Television, aired a report revealing that a number of Ethiopian immigrants to Israel received contraceptive shots either coercively or without their full consent. The investigation also reported an almost 50 percent decline in the birth rate of Ethiopian women in the prior decade.

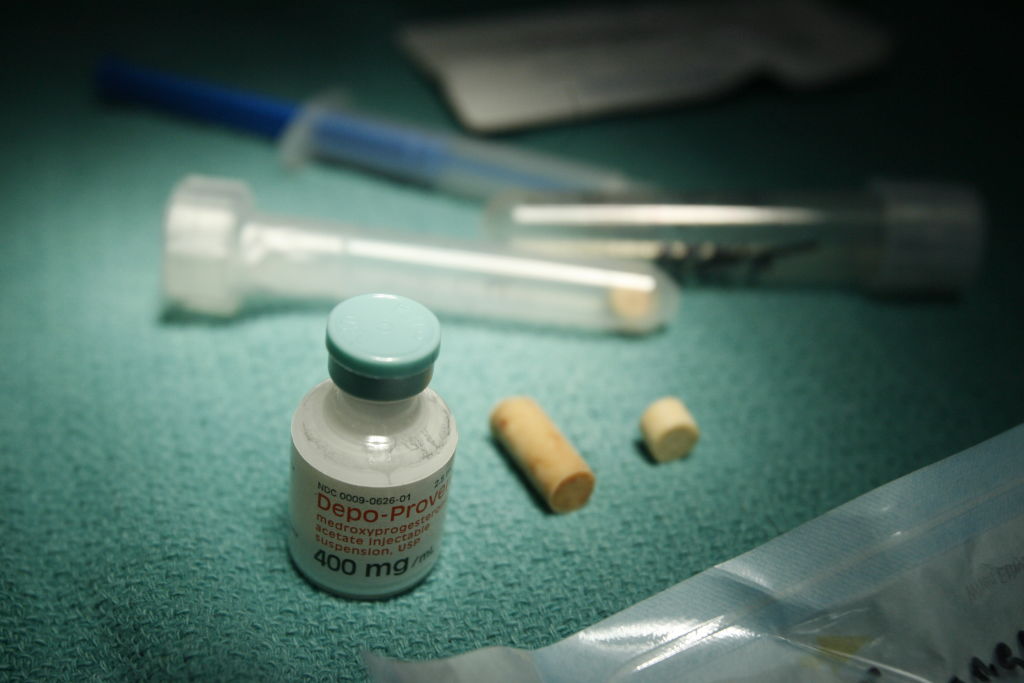

In response to a letter sent by the Association for Civil Rights in Israel in January 2013 and pressure from a number of female members of Israel’s legislature, Ronni Gamzu—the director general of Israel’s Health Ministry—instructed gynecologists in the country’s four health maintenance organizations to cease use of the long-acting contraceptive injection in question, Depo-Provera, if there were any questions around the patient’s comprehension of the treatment. Gamzu reportedly directed medical providers “not to renew prescriptions for Depo-Provera if for any reason there is concern that [the patient] might not understand the ramifications of the treatment.” However, the ministry did not make any admissions regarding the allegations of racially targeted treatment, and the directive was issued for all women.

Depo-Provera—generically referred to as medroxyprogesterone acetate—is a contraceptive injection typically given every three months. The medication suppresses ovulation through the hormone progestin, and is generally considered to be both highly effective at preventing pregnancy and potentially safer than traditional contraceptive medications that act on both progestin and estrogen. However, some research has suggested that Depo-Provera can cause a loss of bone mineral density, leading to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to require warnings on its packaging indicating the medication should not be used for longer than two years.

In February 2013, Deputy Health Minister Yaakov Litzman appointed a team to investigate the use of contraceptive injections in the immigrant community. Three years later, State Comptroller Joseph Shapira wrote in a letter obtained by Haaretz that “no evidence could be found for the claims raised that shots to prevent pregnancy were administered to Ethiopian women under pressure or threats, overt or covert, or in any way that was improper.” However, Haaretz later reported that Shapira did not speak to any of the original complainants, drawing criticism over the scope of the investigation. Similarly, the Jewish Agency and Joint Distribution Committee—two of the organizations under investigation—are not legally subject to state comptroller investigations and thus were not required to turn over their information.

From the available evidence, it appears likely that some Ethiopian women were given contraceptive injections without fully understanding the potential side effects or their alternative options. However, there is no clear evidence indicating that the Israeli government or humanitarian organizations involved purposefully coerced women into receiving injections in an effort to reduce birth rates—though the narrow scope of the investigation into those claims has been criticized.

Claims that this contraception regime led to a decrease in the Ethiopian community’s fertility rate are similarly difficult to validate. A 2016 study in the International Journal of Ethiopian Studies, for example, argues that “the rapid decline in fertility rates among Ethiopian Israeli women following their migration to Israel was not the result of the administration of [Depo-Provera], but rather the product of urbanization, improved educational opportunities, a later age of marriage and commencement of childbirth and an earlier age of cessation of childbearing.”

The claim that Israel was deliberately trying to reduce its Ethiopian population also conflicts with the fact, noted above, that the humanitarian organizations in question—and the Israeli government itself—worked actively for decades to bring large numbers of Ethiopian Jews to Israel.

After Beta Israel received formal recognition in 1973, a number of covert operations directed by the Israeli government, Israel’s national intelligence agency Mossad, and Israel Defense Forces sought to evacuate Ethiopian Jews through Sudan, with Operation Moses successfully bringing approximately 8,000 Ethiopians to Israel in 1984. The United States also contributed significantly to evacuation operations in 1985, transporting more than 500 Beta Israel out of Sudan on six U.S. Air Force C-180 aircraft in Operation Joshua. In 1991, the Israeli military evacuated 14,325 Jews in a covert airlift. According to statistics released by Israel’s Central Bureau of Statistics, as of November 2020 there were approximately 170,000 Ethiopian immigrants living in Israel, 67,800 of whom were born in the country.

If you have a claim you would like to see us fact check, please send us an email at factcheck@thedispatch.com. If you would like to suggest a correction to this piece or any other Dispatch article, please email corrections@thedispatch.com.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.