Walking through downtown Portland, Oregon, in December 2019, I noticed a lot of empty storefronts. I’d until recently lived in the city, and while one gets accustomed to businesses aging out of popularity (furrier, anyone?), about one-fifth of businesses I’d seen open earlier in the year were now gone. Maybe landlords had gotten greedy? Or maybe Portland, which a decade earlier had been considered a “youth magnet” city, had lost its appeal.

Two months later, COVID-19 started to burn through the country. With the first cases next door in Washington state, Oregon locked down swiftly, a move that proponents believe kept the state’s infection and death rates low (192,000 and fewer than 2,600 respectively), if at an economic cost, especially to Portland’s downtown: On top of 80-plus already unoccupied spaces, 190 closed temporarily or permanently.

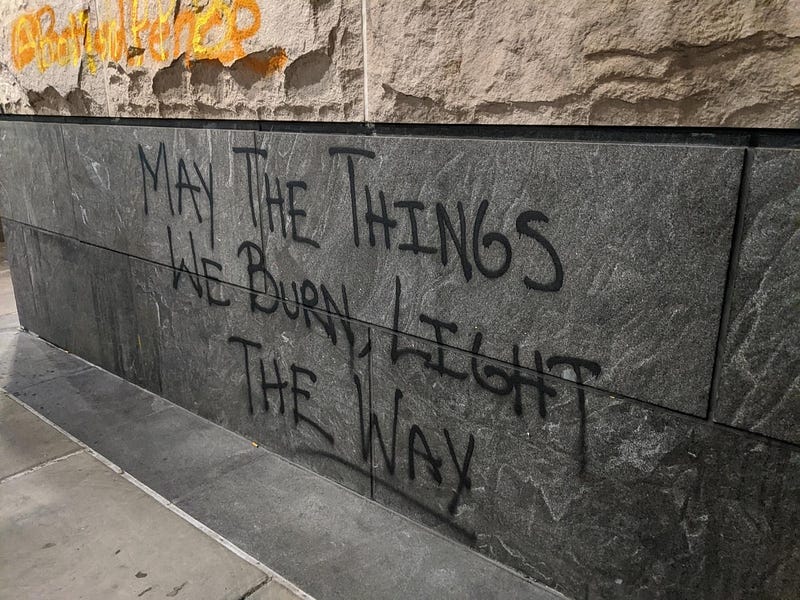

Then George Floyd was murdered. While as many as 10,000 Portlanders marched in support of Black Lives Matter, a small portion—50 on some nights, 600 on others—decided the way to address Floyd’s death, to assuage something they felt was killing the American soul, was through destruction. These protesters—some self-identify as Antifa or black bloc, others call them rioters or anarchists—set fires, broke windows, and mixed it up with whatever authority figures they saw as standing in their way that day. Some Portlanders viewed these actions as justified, others considered them smashing for the sake of smashing.

“It’s just people breaking things,” a commercial realtor told me. “They’re just criminals.” With office towers emptied because of the pandemic, and storefronts busted up indiscriminately, downtown became both barren and unpleasant. With so little in operation, locals stayed away. So did tourists. The homeless population burgeoned. Crime shot up, including rampages that kept Portlanders wondering whether the next incident would be on their block, their business strip, their Boys & Girls Club.

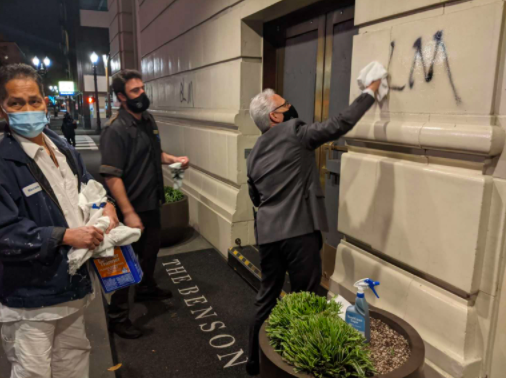

To stay or abandon Portland? It’s a real question, for those considering whether to spend their creative and financial capital in the Rose City. Almost every night since May 27, 2020, some area of the city has succumbed to violence. Much of it is centered downtown, at the federal courthouse and police station, but also at local landmarks like Powell’s Books, the Benson Hotel (where nearly every U.S. president since Taft has stayed), and the Oregon Historical Society (vandalized in October and again in April). The presence of plywood facing covering up storefronts along Broadway, where the city’s main department stores and entertainment venues are located, now moves into its second year. This has not gone unnoticed by the outside world, and if I had a nickel for every person who in the past two months has asked whether Portland is a good place for a family vacation, I’d be clocking about a buck twenty.

With the city’s restaurants reopened for indoor dining on May 7, and the region’s notoriously dreary winter weather giving way to the fecundities of spring, the city might reasonably expect to latch back onto the 126 months of economic expansion it had seen in January 2020.

“It all comes down to confidence, right? Confidence in the city’s ability to secure the basic services that make commerce possible,” said Andrew Hoan, CEO of the Portland Business Alliance. “Intel just announced there will be more factories here in the Portland region. So I think the question: do we still have economic swagger? The answer is yes.”

That’s one way to look at it.

“Personally, I am so happy to be out of that shithole,” said Ron Avni, who, after operating a half-dozen successful Portland restaurants, divested from a city he saw as putting the welfare of protesters ahead of the needs of small business. “The nihilists of Portland are always looking for excuses to ruin the productive segment. And the city does nothing to stop them.”

Avni told me this in January, the day after his former restaurant Shalom Y’All, which featured the foods of his native Israel and is currently under remodel, had its outdoor furniture trashed and the words “Free Palestine,” “scum” and “murder” spray-painted on its face.

“The irony is one of the partners in the business is Palestinian,” Avni said, from his new home in Austin. “It doesn’t matter. They come for you anyway.”

Avni’s fatalism is not unfounded, nor is the concern that Portland does not do enough to stop the destruction. When the violence started last summer, the Portland City Council demanded a $50 million cut to the $241 million police budget. (They got more than $15 million.) Did Portland mayor Ted Wheeler like that the city’s main police station was being attacked every night? No, but he (and the vast majority of Portlanders) liked Trump even less and thus, when the Trump administration sent federal troops to Portland to protect federal property, the grudge match played out in the media, with Wheeler telling Trump to, “Stay the hell out of the way,” and Trump calling Wheeler, “a fool.”

What this meant in practical terms was a new district attorney who declined to prosecute more than 900 of 1,000 people arrested in the act of protesting in the second half of 2020, including many who committed property crimes. And so the violence not only continued, it grew more brazen; when protesters marched to Wheeler’s downtown condominium and demanded he resign, he chose to move rather than confront them. Only after Trump was voted out of office did Wheeler take a tougher stand on the continuing violence, asking citizens to help “unmask” the perpetrators. That request earned him the enmity of those sympathetic to the protesters and left an administration all but defenestrated.

“We have a mayor that is hated by the right and has now become a favorite punching bag of the left,” said Matt Kaye, who with his wife owns two Japanese restaurants on the city’s east side. “Portland has a proud history of political and social activism, but when it comes to the bevy of issues and the well-being of the business community, we are a city of handwringers, long-sighers, and eye-rollers.”

I asked Kaye (who, full disclosure, took over a space of a business my husband sold in 2020) what made him decide to open a second location during both the height of the pandemic and the protest violence. “We made the decision to expand before the shitstorm rained down on us,” he said. “We could have closed, or paused, but we were afraid of losing relevance.”

Kaye’s locations are two miles from downtown, but both butt up against other areas that have seen considerable unrest, including a police station a mile away that’s been attacked more than a dozen times. Even closer is Portland’s Red House, site of a quasi-autonomous zone earlier this year. While the protest was ostensibly undertaken as a stand against gentrification and in support of a black and Native American family who’d lived in the home for six decades (if more basically about a house that had been foreclosed on for nonpayment), the area became befouled with trash and human waste and, to the distress of neighbors, some occupiers open-carried rifles.

“Our employees and loyal neighborhood customers buoyed our spirits, but it was really a tough, long haul that’s not over yet,” said Kaye, who, unlike Avni, has felt supported by the city. “There’s grant money to be found and the street-side dining program has been very effectively administered,” he said. “I’m optimistic about the long-term future of Portland businesses.”

“I haven’t heard many people leaving,” said Vanessa Sturgeon, president of a commercial real estate company in downtown Portland. “To be perfectly honest, the media in general has really overblown the Portland story. You have people calling from all over the country saying, ‘Is it safe?’ Downtown is perfectly safe during the day.”

Sturgeon does not deny it’s been a rough go. “It’s undoubted that business has taken a hit,” she said. “The retail tenants often have to leave their boards up because they don’t have insurance for [the windows] anymore. When they’ve gone to renew, they’re unable to procure insurance without a civil unrest clause. Almost every business that’s getting hit by these rioters, it’s coming out of pocket, and most of them are small businesses.”

With COVID on the wane and people getting vaccinated, downtown is starting to look less ghostly. “From what I hear from restaurant owners—because downtown is a very good restaurant market when there’s tourism—is that it’s active,” said Sturgeon. “People can at least see the finish line here.”

I do not doubt that Portland will regenerate. The people who came to the city in the aughts brought a love for making things by hand, things visitors also loved, whiskey and coffee and snowboards and bikes. The annual waterfront blues festival can draw more than 120,000 people. Wine country is thirty minutes away. Yet for the city to recover some or all of the $5.6 billion visitors spent in the metro area in 2019, it may need to project something of this image to the world, or some other image than the one currently being transmitted. A friend who visits Portland twice a year recently told me she’ll skip it this summer.

“Last summer I was devastated to see the decline,” she wrote. “I was wondering if Portland even factored in the loss of tourist dollars when they allowed the chaos?”

“Am I optimistic or pessimistic about the city? Hmm… on the pessimistic side,” said Sally Krantz, co-owner of a CBD-infused beverage company. “The trash situation is out of control. I know it’s partly because of the pandemic, but there are now rats everywhere. And Ted Wheeler is an ineffective dope. Everything from the riots to the amount of garbage and the fact that the homeless have taken over the city frankly reminds me of when I lived in [New York mayor] Ed Koch’s Manhattan. I would have voted Wheeler out, but the alternative? A woman whose career was in food service and wore a Mao/Stalin/Che skirt to a campaign rally?”

While Krantz said her business has not been affected by the protestors, her life has been.

“I live only a couple of blocks from the Red House, which was a nightmare,” she said. “The amount of havoc generated by them, the buses had to divert because they had barricaded [the area], the businesses forced to shut because people couldn’t physically get to them and then when they could, found them vandalized. And for what? For a family that didn’t pay their mortgage. Life in Portland seems to be a constant battle between people unwilling to see reality and want to live like Ken Kesey on the magic bus, and those of us who understand that you have to pay your mortgage and get your kids to school.”

From covering the protests all summer and fall, I know that the people doing damage to the city are little more than kids themselves. The argument that they are a tiny minority of the population is true. Still, a few hundred people a night busting things up beams a message that the city is okay with this, even if it’s not. I don’t know how long it takes for perception to become reality, to, maybe, become its own form of attraction; a signal to people who appreciate the continuing chaos. And if the acts of violence are both ongoing and indiscriminate, if the enemy can be Trump or Wheeler or the police or an Israeli restaurant, then how do citizens regain a sense of equilibrium and security, and when?

“That’s a complicated question, about a sense of security,” said Portland Business Alliance’s Andrew Hoan. “The first thing that we would look at is, what are the job impacts? What are the consequences to real estate? Have we reversed the economic and demographic trends that have benefited this region for a decade? If you went backwards in time to February of 2020, Portland, Oregon had ascended the economic ladder in every single category.”

Hoan ticks off some hopeful metrics as of February 2020: “We’d seen enormous increase in median household income, in the regional population, in the diversification of the job market. We had seen construction trends, both in commercial and residential, on par with places like New York City in terms of the number of cranes that were dotting our skyline. And so COVID hits. You add on historic wildfires, [you add] political violence, and you would naturally assume that those trends have been reversed. And at least as of January, when we conducted a massive economic analysis of the impacts over the past year, it has not. … We continue to see massive inflow. If anyone questions the resilience of this region, then they gotta sit down and check their pulse.”

Maybe. Maybe the people sticking with or moving to Portland don’t mind unpredictability. Maybe they think it’s a phase. Maybe being a youth magnet city inevitably means drawing the equivalent of rowdy teenagers, maybe they’ll grow out of it.

“The reasons we all moved here—and chose not to move somewhere else in the last 15 months—are all still here,” said restaurateur Matt Kaye. “We all want to go to our favorite shop or restaurant downtown, though sadly, many of them are no longer, see a concert at the Schnitzer or at the waterfront. I think, I hope [our] collective wills and desires, combined with more functional governance, will contribute to the return of a healthy business community. But short-term? We have a mess on our hands.”

Nancy Rommelmann is an author and journalist based in New York. Follow on Twitter @nancyromm

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.