Halloween was widely celebrated in Shanghai, perhaps more than in Western cities. Thousands of costumed young people flocked to the city’s art deco core—a remnant of its jazz-age colonial past—joining dozens of parties set to the tune of Michael Jackson’s Thriller and other festive staples. Even the timing was perfect, as late October comes with cool breezes and golden ginkgo leaves beneath azure skies—a reprieve from Shanghai’s notoriously hot summers and damp, frigid winters. But 2024 was different. With little notice, police rounded up costumed partygoers, took them to stations, and forced them to remove their makeup and costumes before registering their names, IDs, and phone numbers. Uniformed officers posted notices stating, “All cosplaying is prohibited, and no Halloween makeup will be permitted.” Even the weather turned, with unseasonal rains soaking the streets.

Authorities in Shanghai remain on edge following the White Paper protests of November 2022, when thousands of youth took to the streets in response to draconian COVID prevention measures and the economic and social hardships that came with them. Moreover, many tongue-in-cheek costumes mocked pandemic prevention workers and other sensitive topics during last year’s Halloween festivities, something authorities were unwilling to bear this year. Elsewhere in the country, there are signs of growing economic discontent. Workers regularly protest layoffs and unpaid wages at the many struggling factories that dot the southern provinces. There were 719 such incidents in the first half of this year, compared to 696 during the same period last year and just 37 strikes in all of 2022. Many of these labor disputes have provoked violent responses from authorities, most infamously when riot gear-clad police beat workers outside a Foxconn iPhone plant in Zhengzhou in November 2022.

China’s domestic crackdowns belie a deep and growing sense of fear among its political elites. This insecurity runs counter to the frequent media portrayal of China as a confident and rising superpower and speaks to the growing economic and social crises gripping the country.

Manufacturing crisis and unemployment.

China’s manufacturing sector, the country’s largest generator of desperately needed foreign cash and investment, has fallen on hard times. Exports have fallen below expectations amid a softening global economy, reduced domestic demand, and increased competition from emerging markets such as India, Mexico, and Vietnam. Although China aims to transition toward “high quality” manufacturing, including items such as electric vehicles (EVs) and batteries, rising protectionism on the world stage threatens its export prospects, especially following the recent election of Donald Trump. Despite significant investment and potential, some 52,000 Chinese EV-related companies shut down last year amid weakening demand and rising raw material costs. Many analysts blame significant government subsidies to the industry for creating overcapacity—a problem that is hardly exclusive to the EV sector.

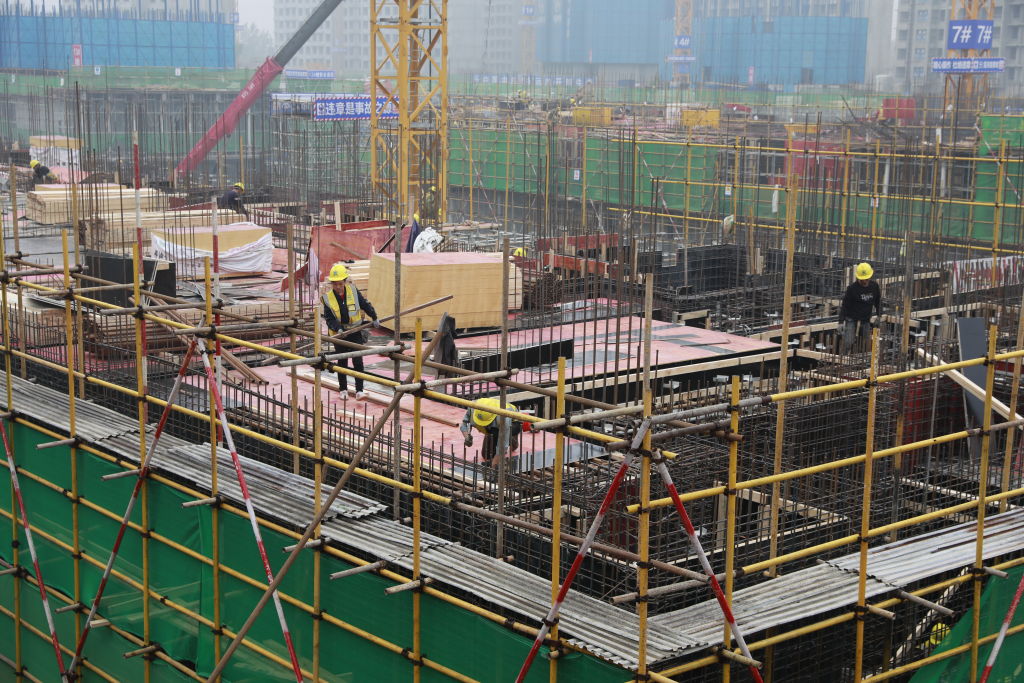

These factors, combined with the 2020-2023 regulatory crackdown on the country’s tech sector, have sent unemployment figures soaring. According to official figures, roughly 1 in 5 urban youth between the ages of 16 and 24 in China is unemployed. Last year, President Xi Jinping addressed concerns over these figures by claiming that young people should “eat bitterness,” suggesting college-educated youth are not above manual work or moving to the countryside. Current unemployment figures also mask the true scope of the problem, as they do not count rural workers, who make up the vast majority of the country’s nearly 300 million migrant workers. Amid a significant downturn in manufacturing and construction activity, these largely invisible workers are likely suffering the most.

“Chinese society is rife with disillusionment, particularly among young people. Many have chosen to ‘lie flat’ as part of a growing online movement to cut spending, live on savings, and avoid work at all costs—a trend China’s ubiquitous online censors have been quick to block.”

Consumer spending—a bellwether for public prosperity and confidence—has not recovered since COVID. Dalian Wanda, owner of the country’s largest chain of shopping malls, is now selling off its retail assets in a desperate bid to stay afloat. Online retailers also report a significant slump in sales, even during major holidays. With conditions like these, social upheaval has become a potent threat. Students of Chinese history know that such conditions can produce sweeping and lasting consequences.

A crisis of supply and demand in the property market.

Homes have historically been the preferred investment choice in China, where people have few options for acquiring long-term assets. Stock investments are notoriously risky because of political interference and a lack of transparency in the equity markets, and capital controls make foreign investment practically impossible for all but China’s wealthiest and best-connected elites. For these reasons, Chinese people tend to invest in residential property due to its consistently rising value over the past three decades, and it is not uncommon for wealthy people to own several homes.

Rampant speculation in the housing market made homes increasingly unaffordable, even among urban white-collar workers, whose wage growth did not match soaring home values. By 2021, purchasing a home in China cost around 29 times the average annual salary, compared to just 5.6 times currently in the United States. Millions of young people have forgone marriage and children as a result, exacerbating the country’s fertility crisis.

China currently has more vacant homes than people to live in them, according to former National Bureau of Statistics official He Keng, who made a rare public critique of his country’s housing crisis last year. Despite rising prices, empty homes and high-rises have dotted the Chinese landscape for years. However, with home prices still rising on demand from wealthy speculators, developers continued to build new units—at least until the credit dried up in late 2020. To make matters worse, as China’s demographic crisis continues to worsen, there will be fewer young people to buy homes in the future. In this way, China’s property market remains gripped in a spiraling crisis of extreme oversupply and dwindling demand. This crisis makes the massive debts incurred by property developers wholly unsustainable in the long term.

Policymakers have known about this issue for years. In 2012, during the administration of President Hu Jintao, then-Premier Wen Jiabao called for a better-regulated property market in response to high prices. The regulations Hu’s successor, Xi Jinping, delivered eight years later transformed the issue into a more immediate crisis.

How ‘three red lines’ ignited a meltdown.

In August 2020, Chinese regulators issued new rules limiting property developers’ access to credit based on their debt burden. It placed each developer into one of four categories according to their debt-to-asset ratio—denoted by “three red lines”—limiting their access to further loans accordingly. However, by radically limiting the flow of cash to property developers, these reforms set off a dramatic chain of events.

The subsequent credit crunch sent shockwaves throughout China’s economy. Bankruptcies at the country’s two largest property developers—Evergrande and Country Garden—were just the beginning. After a decades-long bonanza, cash-strapped developers have abandoned thousands of construction sites nationwide, leaving buyers holding the bag. Many completed homes are of the “tofu dregs” variety: crumbling, cheaply built facades that are largely unfit for human habitation, making their true value a meager fraction of current prices. Although several municipal governments have lifted previous restrictions on multiple home ownership to stimulate sales, the structural issues of oversupply, unaffordable prices, and shrinking demographics remain largely unaddressed.

The state has even directed state-owned firms to purchase vacant properties in some regions in a likely attempt to bolster prices. Policymakers are right to be concerned: on average, property makes up 70 percent of Chinese households’ net worth. According to Bloomberg Economics, just a 5 percent decline in home prices would erase $3.6 trillion in housing wealth. In this way, the state is caught in an impossible situation: home prices may be untenably high, but a collapse in home values would eviscerate the net worth of hundreds of millions of homeowners.

The contagion spreads.

The contagion in the property market has spread to other sectors of the economy. For example, China’s steel industry—by far the world’s largest—faces depressed prices and a wave of potential bankruptcies, with nearly three-quarters of the country’s mills suffering losses amid depressed demand from the construction sector. Land sales to property developers once provided more than 41 percent of local government revenue. Now that developers are strapped for cash, land sales have fallen precipitously, causing local government debt to skyrocket.

China lacks the means for local governments to officially default on their debts, necessitating regular bailouts in the form of stimulus cash, refinancing, and other means of rescue. Although the central government could allow some localities to default by other means, this poses a high risk to an already shaky public confidence. Additionally, much of China’s local debt remains hidden due to a lack of transparency in the lending market, especially among the country’s largely unregulated shadow banks. The finance ministry currently estimates hidden debts at around $2 trillion, but that number could be much higher.

The effects of government stimulus measures have been lackluster to date. Although these packages offer brief reprieves in the financial markets, there has been no fundamental economic turnaround as the national debt burden continues to balloon. Last year, China’s official public and private debt-to-GDP ratio reached a record 287.8 percent, placing it among the world’s highest—and this figure likely does not account for the full scope of the country’s hidden debts. Although China previously spent about 16 percent of its GDP clearing up bad bank loans in the wake of the 1998 Asian financial crisis, the country carried much less debt at the time, and its export-driven economy was rapidly gaining momentum. Things are much different today amid slowing growth and a struggling export economy.

‘We are the last generation.’

In May 2022, COVID prevention workers stood in the doorway of a young couple’s home during the infamous Shanghai lockdown. A police officer in hazmat gear claimed that if the couple did not comply with orders to attend a quarantine facility, it would affect their family for three generations. “We are the last generation, thank you,” said the young man, slamming the door in the officer’s face.

Chinese society is rife with disillusionment, particularly among young people. Many have chosen to “lie flat” as part of a growing online movement to cut spending, live on savings, and avoid work at all costs—a trend China’s ubiquitous online censors have been quick to block. Others have protested in various ways despite the severe consequences of doing so. Most worryingly, sporadic attacks on the public, including mass stabbings of schoolchildren and motorists purposely driving into large swathes of pedestrians, are increasingly prevalent: perpetrators tend to be men who lost money on business deals and other economic misfortunes. Government officials have told authorities to be on the lookout for “losers” to target for future surveillance. Such levels of disengagement are not only anathema to an economy and social harmony but serve as painful reminders of previous periods of mass disillusionment and upheaval in the country.

Brutal responses deeply rooted in historical fears.

Since the dawn of a unified China, dissatisfied young people have fundamentally threatened its rulers at key junctures, with internal rebellions overthrowing or severely weakening most historic dynasties. Sparked by a young man named Hong Xiuquan who was unable to secure a coveted civil service job, the 1850 Taiping Rebellion took over much of southern China, lasted 14 years, cost as many as 30 million lives, and nearly destroyed the ruling Qing dynasty. Less than a century later, Mao Zedong’s Communist Party came to power on the heels of a movement that absorbed thousands of disillusioned youth. The current regime is intimately aware of these and similar episodes throughout Chinese history.

As crises mount and censorship falls short, the regime responds to public discontent the only way it knows how: brute force. It is a regime that crushed the 1989 protests in Tiananmen Square with the full might of the People’s Liberation Army, killing thousands. It imprisoned thousands of Falun Gong practitioners in response to their 1999 silent protest in Beijing. Similar stories of persecution abound among the minority Tibetan and Uighur populations. At no time during such crackdowns in the post-Mao era did the regime face an economic and social crisis as profound as the one it faces now. Its future responses could come with similarly brutal intensity. China recently detained one of its top economists over comments he made in a private chat group, signalling how Beijing will likely address dissent over its economic policies moving forward.

Beijing’s hypervigilance is not limited to domestic affairs. The regime tends to blame many of China’s problems on foreigners, and virulent anti-foreigner government propaganda has inspired violent attacks on expats living in the country, including Americans and Japanese. Expats must also now contend with greatly expanded espionage laws that can result in their indefinite detainment on vague charges. China’s increased use of exit bans also keeps foreign personnel in the country indefinitely at their own expense, and since 2022 authorities have raided the offices of several foreign firms. When placed into the context of China’s spiraling domestic crisis, Beijing’s increased fear and hostility toward the outside world may also indicate its growing sense of insecurity at home.

With the economic crisis showing no signs of abating and reforms largely unsuccessful to date, Chinese authorities must increasingly contend with a dissatisfied populace. Amid a spiraling debt crisis and a struggling manufacturing sector, the leadership’s promise of jobs and upward mobility in exchange for young people’s compliance after Tiananmen Square seems impossible to fulfill. These factors leave Beijing little option but to use force to quell discontent at the exact moment it needs its young people to support its rapidly aging society. Unlike historical periods of acute crisis, this time the world will be closely watching how Beijing responds to discontent as elite fears continue to set in.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.