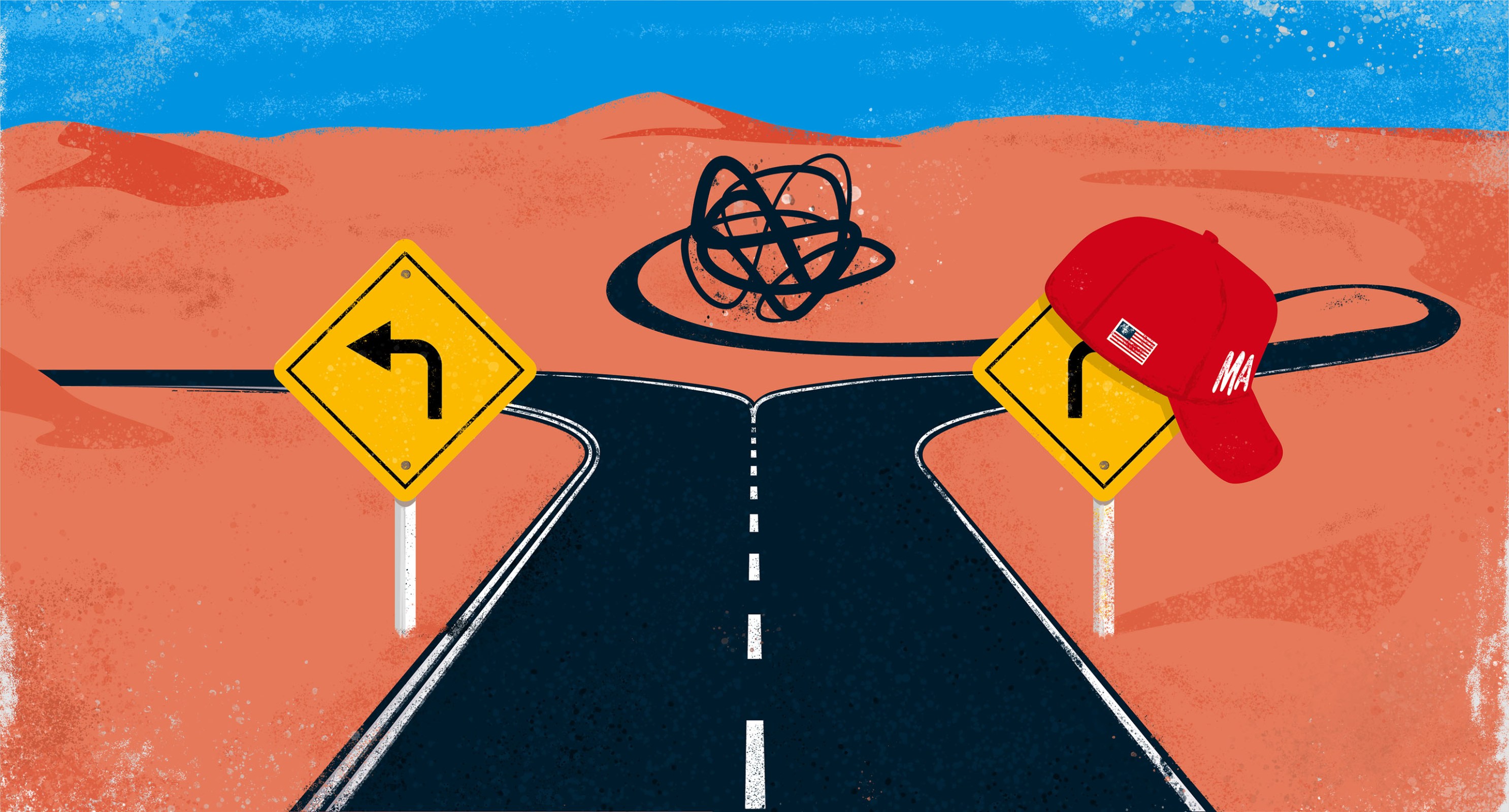

Is the “New Right” conservative?

If you spend any time following the most vocal defenders of Donald Trump or various populist causes generally, some version of this question may have occurred to you. If you find yourself listening to defenders of a supposedly extreme right-wing Republican president’s signature policies, and then wondering aloud, “Wait, I thought conservatives were in favor of free markets?” you have an idea of what I am getting at. If you’re perplexed by the way many on the right celebrate and lionize a rogue’s gallery of libertines, scapegraces, sybarites, caitiffs, roues, abusers, and cads, you might wonder why you didn’t get the memo explaining that the right no longer cares about “moral rearmament,” or “family values.”

In short, if you’re a lifelong conservative, you might be struggling with the question of whether “the right” is where you belong. If being a principled defender of the constitutional order, limited government, free markets, traditional values, and an America-led world still makes you a conservative, are you still on “the right” when the loudest voices on the right reject most or all of those positions?

I ask these questions full of trepidation about getting sucked into what I call the paradox of labels. It is simultaneously true that labels matter a great deal and that arguments about labels can often be a pointless distraction.

So let me make a brief case for the importance of labels. Labels matter because we use labels—terms, constructs, categories, words—to understand reality and chart our course through it, both individually and collectively. If you think labels don’t matter, tear off the labels on all of your cleaning supplies, canned goods, insecticides, prescription medicines, etc. Eventually, you’ll change your mind—or die in the pursuit of making a point.

At the same time, if you invest too much significance in labels, they end up doing your thinking for you. The words become separated from the thing, and arguments about reality become fodder for logical legerdemain and semantic games about terminology. British philosopher Antony Flew popularized the “No True Scotsman” fallacy: If “no Scotsmen put sugar on their porridge,” then a Scotsman’s identity is held hostage to an opinion.

There’s a long history of this fallacy in politics. Pas d’ennemis a gauche, pas d’amis a droit—no enemies to the left, no friends to the right—was a credo for Popular Fronts (more on those later) in 1930s France and Europe generally. A similar spirit has infused the right in the last decade. Highly partisan Trump supporters will routinely insist that no true conservative would oppose him—and suddenly the definition of conservative (or right-wing) is held hostage to support for him. Or even take Trump out of it: In the 1980s, support for a strong national defense against the Soviets was a point of conservative consensus. So promoters of a particular weapon system would try to argue that members of Congress must fund it or be stripped of their conservative insignia, like a cowardly officer being stripped of his epaulets.

The only reliable way out of the paradox of labels is to define your terms. In Kantian terms, the task is to make the phenomenon—for our purposes, the labels—correspond as closely as possible with the noumenon, the thing-in-itself. Specifically, are right-wingers conservative? Or have the once overlapping circles in the Venn diagram parted from each other, like two celestial bodies following different paths after a long eclipse?

Wings of the right.

Finding useful definitions of right or right-wing that distinguish between conservatism and “right-wingness” is almost as hard as writing them. The massive Encyclopedia of Conservatism has an entry on the “New Right” but not on simply “The Right.” Most definitions treat “right” as a synonym for “conservative.” Dictionary.com says “of or relating to political conservatives or their beliefs.” The entry for “Right” in The Routledge Companion to Fascism and the Far Right glossary begins “General shorthand for ‘conservatives,’ as opposed to the forces of change.” Wikipedia’s entry on “Right-wing politics” gets closer to something usable: “Right-wing politics is the range of political ideologies that view certain social orders and hierarchies as inevitable, natural, normal, or desirable, typically supporting this position based on natural law, economics, authority, property, religion, or tradition. Hierarchy and inequality may be seen as natural results of traditional social differences or competition in market economies.”

This is more useful because it acknowledges that there are a “range of political ideologies” that fall under the label “right-wing.” This at least allows for the possibility that conservatism is just one of many ideologies on the right.

Another way to illustrate the point is to consider the “alt-right.” Most people who call themselves conservatives reject the alt-right’s embrace of antisemitism, racism, and nativism. But they also might concede that the alt-right is a form of perverse hyper-patriotism. In some cases it might be, but there is also a strong strain of anti-Americanism in the “alt-right” itself. As Richard B. Spencer told the New York Times a decade ago, “America as it is currently constituted—and I don’t just mean the government; I mean America as constituted spiritually and ideologically—is the fundamental problem.” Regardless, the very name “alt-right” illuminates the fact that, just as there are different kinds of conservatism, there are different kinds of right-wingery.

But for now, what I broadly mean by right-wing is a bundle of different ideologies and attitudes that see themselves in opposition to the left. I would go a step further and argue that the more radical segments of the right are more like mirror images of the radical left. Just as identitarian, statism, illiberalism, and anti-Americanism define or describe some elements of the radical left, they also describe some factions on the radical right.

A good working definition of right-wing is simply the tribe that hates the left. Of course, this can get the causation backwards, because often what gets defined as “the left” is whatever the right hates at a given moment. Want more than two dolls for your daughter? You must be a lefty!

The right is most often defined by what it opposes. At the philosophical level, egalitarianism tops the list. After that, many of the defining features of what counts as “the right” are more symbolic or even aesthetic. The right tends to draw on traditional culture and symbols, and often looks through a gauzy nostalgic lens to the past for inspiration as opposed to the left’s vision of a utopian future ahead of us. Conservatism does this, too of course. But to the extent that conservative and right-wing are not synonymous terms, the differences have to do with the fact that conservatism is also for certain things, and has avowed limiting principles.

Think about it this way. There is a continent we can call right-wing, and conservatism is a country on that continent. But that country has borders. Beyond those borders are wildlands with many right-wing tribes that may share some things in common, but are nonetheless not conservative.

Regardless, for the moment all I ask is that you hold out the possibility that conservatism and right-wing are not necessarily synonymous terms.

Conservatism in more than one sentence.

When William F. Buckley Jr. was tasked with defining conservatism, the title of the essay he produced illustrated how difficult he found the exercise: “Notes Toward an Empirical Definition of Conservatism: Reluctantly and Apologetically Given.” Buckley recounted how he was often asked to define conservatism in one sentence—to which he replied, “I could not give you a definition of Christianity in one sentence, but that does not mean that Christianity is undefinable.”

Conservatism, properly understood, is both a way of thinking, consciously and unconsciously, and the product of that thinking. In other words, conservatism is not an identity the way that race, sex, or even, to some extent, religion are understood to be identities. Truisms about personality types notwithstanding, no one is “born conservative” any more than someone is born a Fabian Socialist.

The Catholic philosopher G.K. Chesterton provides one of the best illustrations of a kind of conservatism in his parable of the fence, which first appeared in his 1929 book The Thing:

There exists in such a case a certain institution or law; let us say, for the sake of simplicity, a fence or gate erected across a road. The more modern type of reformer goes gaily up to it and says, “I don’t see the use of this; let us clear it away.” To which the more intelligent type of reformer will do well to answer: “If you don’t see the use of it, I certainly won’t let you clear it away. Go away and think. Then, when you can come back and tell me that you do see the use of it, I may allow you to destroy it.”

Chesterton is clearly not opposed to reform. His point is humbler than that. Reform may be necessary, but you first must know why it is necessary, and you must understand what you are reforming and how to reform it. Find out why the fence is there first, and if you learn it no longer serves its original—or some other—useful purpose, perhaps the fence should come down. But perhaps not. Maybe it’s not worth the effort. Every action should be subject to some kind of cost-benefit analysis. The time and expense you spend dismantling the fence might be better spent elsewhere. Change may be necessary, but change for its own sake is not reason enough. And it certainly isn’t conservative. In short, conservatism is a way of making decisions, which includes deciding to do nothing.

Let me emphasize a point that you might have skimmed past. Just because a fence—by which Chesterton means an institution, rule, or custom—was erected for one purpose, it doesn’t necessarily follow that the fence should be torn down even if its original purpose no longer applies. A tree that was planted for shade may no longer be necessary for that purpose after the man who planted it has moved on. But now the tree might be a habitat for desirable birds, it might prevent soil erosion, it might be support for a treehouse, or it might simply be a thing of beauty. One could argue that the institution of marriage began largely as a mechanism for forging alliances, transferring property, and legitimizing heirs. It still serves some of those functions, but its roots have grown deeper and spread wider, and its canopy provides cover for far more than just that.

Let’s illustrate the point with a relatively recent controversy.

Elon Musk is darling of the right, partly for his robust house-cleaning of the federal government. But time after time, Musk encountered Chestertonian fences without bothering to find out why they were there in the first place. One of the few times he explicitly acknowledged erring was in cutting a program to combat the often lethal disease Ebola. “We will make mistakes. We won’t be perfect,” he said in a White House meeting. “When we make mistakes, we’ll fix it very quickly. So, for example, with USAID, one of the things we accidentally canceled very briefly was Ebola prevention.” But, he insisted, “We restored the Ebola prevention immediately—and there was no interruption.”

The problem? Even though Musk claimed to have restored the funding, he didn’t understand how the system works (or he lied) and the program remains hobbled amid a fresh outbreak in Africa. Four of the five contracts to fight the disease were canceled, and while two were restored, the remaining two—the financial bulk of the program, as it turns out—remain canceled as of this writing. But even if the error is fully corrected, the cost in lives and America’s reputation cannot be retroactively fixed. The conservative understands that once an old tree is torn down in error, simply planting a sapling doesn’t wholly rectify the problem. “The conservative declares that he acts only after sufficient reflection,” Russell Kirk wrote, “having weighed the consequences. Sudden and slashing reforms are as perilous as sudden and slashing surgery.”

In other words, a radical, slash-and-burn approach to government functions can be described as “right-wing”—Elon Musk owned the libs by ransacking their bureaucratic citadels, after all—but that doesn’t mean it is conservative.

Three conservatisms.

There are, roughly speaking, three relevant understandings of conservatism. The first, and closest to Chesterton’s discussion of the fence, is what is commonly called the conservative “temperament” or “disposition.” The underappreciated British philosopher Michael Oakeshott was a champion of the conservative disposition as a non-ideological orientation toward life: “To be conservative, then, is to prefer the familiar to the unknown, to prefer the tried to the untried, fact to mystery, the actual to the possible, the limited to the unbounded, the near to the distant, the sufficient to the superabundant, the convenient to the perfect, present laughter to utopian bliss.” This is what Kirk meant when he frequently insisted that conservatism was the “negation” of ideology. Or as Abraham Lincoln put it: “What is conservatism? Is it not the adherence to the old and the tried, against the new and the untried?”

It’s worth noting that in the 19th century, Americans generally used the word “conservative” as synonymous with “moderate,” “reliable,” “steadfast,” and “commonsensical.” This conservatism, at its most basic level, is the antonym of “radical.” Radical is derived from radix, or “root,” and has come to mean something akin to tearing everything down. While some radicals are nihilists who just want to see the world burn, radicalism is more firmly implanted in the utopian vision. Radicals seek to raze the status quo and the tyranny of the imperfect now with some conception of the perfect future.

In his landmark 1957 essay “Conservatism as an Ideology,” the American political scientist Samuel Huntington observed that “no political philosopher has ever described a conservative utopia.” That’s because conservative political philosophy is not interested in such projects, because conservatives understand that utopias are impossible in this life—“utopia” literally means “no place”—but also because conservatives like or at least accept much of what they see in the world as it is. When your standard isn’t utopian perfection, your tolerance for the world as you find it increases. Again, per Chesterton, reform is often necessary, but not to create a perfect world, but to get closer to a “eutopia”—a good place.

As Huntington observed, this is why, among major philosophical political orientations, only radicalism and conservatism have no inherent, universal, programmatic content. Socialism and nationalism may have local and cultural “characteristics,” but the idea is pretty much the same everywhere. Radicalism and conservatism may have some universal characteristics, but what the radical seeks to tear down, and what the conservative seeks to conserve, are different in every society. For instance, a conservative in the Soviet Union was the most doctrinaire of Bolsheviks. To the “conservative” Bolshevik, the liberalizers, the small-d democrats, or champions of the free market were the radicals, wreckers, and reactionaries. To the conservative in America, those who would dethrone our liberal constitution, the rule of law, or the free market, are the radicals.

The beaver and the termite.

Again, some radicals do have visions of creating something better, after they tear down what is. Radical Marxists have a utopia waiting for them at the end of history. But it is a truism that embracing radical means in pursuit of some lofty end tends to result in a love of radicalism for its own sake. Che Guevara, Lenin, the Jacobins, the Weather Underground: they all may have started with lofty goals, but ended up seduced by the thrill of violence and terror. This happens because radicalism tends to manifest itself as a lust for power, and the lust for power is then used to justify further radicalism. Still, some radicals do succeed in toppling the established order, but the new order they create is often far worse than what they destroyed. And because they rejected the rule of law in pursuit of power, they tend to use law merely as a means to rule for their own benefit. This is the story of countless “national liberation” movements of the left and the right. The once-lofty ideas about the ends they sought are replaced by authoritarian or totalitarian juntas. This story is so common it would be easier to list the exceptions than the examples.

Philosophically and psychologically, one can think of radicals as termites: wherever you put them, they are only interested in eating what is in front of them. A beautiful antique grandfather clock or a dilapidated fence in a field? They’re both just meals to termites. Conservatives, rightly understood, are more like beavers. They build institutions from what is available to them and fortify and improve the projects that already exist. Their projects serve as bulwarks against the torrent of change brought by the endless river of time to create good places, safe harbors, to live and thrive in. This is the conservatism of, say, the Catholic Church: Hold fast to that which must not change but adapt and reform on the things that can and should change (which is not to say that Church leaders do not struggle to draw those lines). Indeed, this kind of conservatism can be found on the center-left. Contrary to a lot of childish right-wing rhetoric, not all Democrats are radicals. I may not agree with their policy proposals for practical reasons, but they are generally not seeking a wholesale transformation of society (even if they sometimes foolishly pretend to do so for electoral purposes). They are not ideological conservatives, but they are temperamentally or culturally more conservative than they might admit.

And that brings us to the second kind of conservatism: Ideological conservatism in the Anglo-American tradition. The “Anglo-American” qualification is necessary because, again, a conservative in one place often seeks to conserve very different things than a conservative in another place. Historically, in America, a conservative seeks to protect, defend, and pass on to the next generation the principles of the founding and the blessings of liberty. There are, of course, related forms of ideological conservatism in the realms of morals, traditions, and various religiously informed values. But all of these conservatisms share a worldview that holds that change should be greeted with some suspicion because some fences are worth keeping, even if they have outlived their original purpose, because they are lovely and in their loveliness still serve other purposes.

Change is sometimes necessary—that’s why we amend the Constitution from time to time—but those changes are in service to a eutopian gratitude for what is good. “To my mind, conservatism is gratitude,” the political analyst Yuval Levin explains. “Conservatives tend to begin from gratitude for what is good and what works in our society and then strive to build on it.” One might say that conservatism is beavers all the way down.

Historically, in America, a conservative seeks to protect, defend, and pass on to the next generation the principles of the founding and the blessings of liberty.

But the point missed by those conservative intellectuals—led by Russell Kirk, who insisted that conservatism is antithetical to ideology—is that in an ideological age, a merely conservative temperament or disposition is a recipe for drift. This was the political philosopher Friedrich Hayek’s claim in his famous essay from 1960, “Why I am Not a Conservative.” It is the “fate of conservatism to be dragged along a path not of its own choosing,” Hayek wrote, because a merely temperamental attachment to the way things have always been—or are—is not enough of an argument. It fails to defend on empirical or principled grounds what is good, and thus cannot muster the will to preserve what must endure or to change what must be changed. “This is the way it’s always been,” is the beginning of an argument—but it is not a sufficient argument in an ideological age.

Think of it this way. Many people might support free trade for a host of practical reasons or, simply, because of status quo bias: this is the way it’s been for a long time. But when free trade is overthrown in favor of some mercantilist agenda, free trade needs to be defended with arguments. Ideological conservatism is the weapons cache for those arguments.

Hayek’s essay is often cited as dispositive proof that libertarianism—a label Hayek also rejected—is incompatible with conservatism of any kind. But Hayek himself (who labeled himself an “Old Whig” after Burke) made clear in the same essay that the conservatism he had in mind was primarily the Old World, or European, variant of conservatism—i.e. devotion to throne and altar, aristocracy, etc. He was not talking about American-style conservatism, which was infused with a mission to defend, and promote, the “classical” liberalism of the founding.

The relevant point here is that Hayek recognized that the conflict between conservatism and liberalism was a hallmark of European, not American, history: “There is nothing corresponding to this conflict in the history of the United States,” Hayek writes, “because what in Europe was called ‘liberalism’ was here the common tradition on which the American polity had been built: thus the defender of the American tradition was a liberal in the European sense.” Indeed, Edmund Burke identified the peculiar tendency of the American colonists to defend liberal principles almost reflexively. “In other countries, the people, more simple, and of a less mercurial cast, judge of an ill principle in government only by an actual grievance,” Burke explained in his 1775 speech on Conciliation with the Colonies. But in America, “they anticipate the evil, and judge of the pressure of the grievance by the badness of the principle. They augur misgovernment at a distance; and snuff the approach of tyranny in every tainted breeze.”

In other words, the conservative project in America has been, perhaps not wholly but certainly in large part, to defend the classically liberal project of the founders. Again, American conservatism is about more than merely defending that project. But defending that project—the way William F. Buckley Jr., Ronald Reagan, and Barry Goldwater did and the way George Will, Thomas Sowell, and various “freedom conservatives” continue to—is inseparable from ideological conservatism. Consider that, with the exception of defeating the Soviet Union, the most successful conservative enterprise of the last century has been the conservative legal movement led by the Federalist Society, which is “committed to the principles that the state exists to preserve freedom, that the separation of governmental powers is central to our Constitution, and that it is emphatically the province and duty of the judiciary to say what the law is, not what it should be.” That is a liberal project, because the Constitution is a (classically) liberal charter.

Free markets, limited government, the rule of law, and the sovereignty of the individual are more than sufficient scaffolding around which to construct an actual ideology. And that ideology, or “worldview” if you prefer, is what inspired generations of conservatives. Their ideology didn’t “negate”—as Kirk tediously insisted—their conservatism, it gave them a practical program for how to engage in politics.

This matters because many on the “New Right” claim to be on the side of Western civilization, while simultaneously contending that liberalism isn’t part of our civilizational inheritance. This is nonsense. Liberalism has its roots in Ancient Greek, Roman, Jewish, and Christian ideas (and more than a few Germanic and English customs). Liberalism runs through Western civilization like a broad and deep river, cutting through mountains and valleys leaving wellsprings of liberal custom and tradition throughout the watershed of the West. The Judeo-Christian foundation of the West is also the philosophical and theological foundation of liberalism. The primacy of individual conscience, the vital necessity of pluralism and separation of church and state, freedom of speech, innate God-given rights: All of these things are the product of Jewish and Christian thought as developed in the West. To argue that these ideas are alien or even peripheral to the Western tradition is to argue for the erasure of that tradition—not its restoration.

Other factions of the New Right mock liberalism as a “value neutral” and “procedural” mechanism that stifles the authentic civilizational, theological, even “manly” nature of the West. This, too, is nonsense. The ideas that one has the right to face your accuser in court, speak your conscience, worship—or not—as you see fit, own the fruits of your labors, are not “value neutral.” They are among our greatest moral achievements.

Fusionism, rightly understood.

So far I’ve avoided using the word “fusionism,” but I can’t put it off any longer. This was the intellectual project of Frank Meyer, a longtime editor at National Review. In short, Meyer’s argument boiled down to the idea that virtue and freedom were not in opposition to each other, but were in fact two sides of the same civilizational coin. Coerced virtue is not virtuous. Freedom uninformed by virtue wasn’t liberty but licentiousness. Meyer believed that this duality lay at the heart of Western civilization—and that the two were intertwined in a productive “tension” like two strands of DNA. Recognizing and attending to this tension was the first step towards a healthy and robust conservatism and civilization. And his fusionist project formed the center of gravity of ideological conservatism from the 1950s until, well, recently. (That is not to say that there were not heated arguments over fusionism and its theoretical or practical viability).

Fusionism is often described by people unfamiliar with Meyer’s arguments and the evolution of American conservatism as a kind of coalitional project, a kind of compromise that allowed people like William F. Buckley Jr. to herd the various tribes of traditionalists, libertarians (or “individualists” as they were often called from the 1930s to the 1960s), and foreign policy hawks. In other words, they see it as the intellectualized version of Ronald Reagan’s famous three-legged stool, which described the different factions in his electoral coalition. The demands of coalitional politics on the right were certainly complementary with Fusionism, but coalitional politics was not Meyer’s primary concern.

I haven’t much discussed the third leg of the stool—foreign policy, specifically anti-Communist foreign policy—because for our purposes, if modern American conservatism fused classical liberalism and moral traditionalism, the Cold War was the forge that fused them together.

It shouldn’t surprise anyone that conservative Cold War intellectuals were receptive to fusionism, but that doesn’t mean fusionism was some vanity project of eggheads, little magazines and think tanks, as many on the New Right insinuate. The Communist threat served to fuse these commitments in the hearts of millions of Americans: Faith in economic freedom and traditional values—the American way!—buttressed the arguments for standing up to “Godless communism.”

To illustrate the point, consider that, thanks to a grassroots effort by such groups as the Knights of Columbus and Daughters of the American Revolution, the phrase “under God” was added to the Pledge of Allegiance in 1954 as a direct rebuke to our Soviet adversaries. In 1956, “in God We Trust” replaced the unofficial motto, “e pluribus unum,” as the official motto of the United States. America was a religious country long before the Soviet Union was founded, but the existence of the Soviet Union and the threat it represented forged an ideological recommitment to what makes us different. As Thomas Sowell writes: “It takes an ideology to beat an ideology.”

Phrases like fusionism, the “three-legged-stool,” or “the (zombie) Reagan consensus” are often derided by today’s New Right, in part to imply that this consensus was an elite, top-down construction of coalitional politics that, whatever its former merits, the demands of this moment render the old consensus irrelevant at best, and an impediment to what must be done now. But, the truth is that American conservatism was organically and holistically— i.e. culturally—a fairly unified worldview reflecting these different commitments without much sense of internal contradiction or tension. From the end of World War Two until, again, recently, to say someone was conservative was to suggest they were socially conservative, supportive of the free market and limited government, and in favor of a strong national defense, all at once.

The Populist Front.

That covers the first two kinds of conservatism I wanted to touch on: dispositional and ideological. But what about the third?

That’s the easiest to define, because the definition rests solely on what people who call themselves “conservative” believe, or claim to believe, at any given moment. This definition is the dominant understanding of conservatism in the media and in partisan politics. When news outlets report that “conservatives”—at the Heritage Foundation, CPAC, Congress, or in the White House—now embrace industrial policy, or protectionism, or when they reveal that leading conservatives have no problem with Matt Gaetz’s or Pete Hegseth’s (or Donald Trump’s) sordid sexual histories, all of the philosophical distinctions outlined above are irrelevant, save perhaps as fodder for pointing out inconsistency or hypocrisy. If the vast infrastructure of “the right”—the Republican Party, partisan media, donors large and small—declares that conservatives now believe in state planning, autocracy, mercantilism, and the advisability of putting mayo on a pastrami sandwich, then simply as a journalistic and conversational matter, that’s what conservatism is.

It should come as no surprise that I think this is wrong.

One remedy for this is simply to resort to clarifying adjectives. The American journalist Jay Nordlinger long ago exempted himself from label fights by embracing the term “Reagan conservative,” or simply “Reaganite.” There’s much to recommend this practice, but one downside is that it abandons, at least rhetorically, any effort to defend unqualified conservatism from those who would bend its meaning to the demands of a New Right popular front.

At this point it would tax the patience of any reader who has made it this far to get into a detailed history of the concept of the popular front. So, very briefly, popular, or united, fronts were formed in the 1930s in France, Spain, and elsewhere for the ostensible purpose of fighting fascism. (Nostalgia for such efforts lives on in corners of the left in America and Europe.) But the Popular Front was never a pluralistic coalition of intellectual tolerance among various tribes of the left; in fact the party line was viciously enforced, and ironically, many of the founders of modern American conservatism were exiles from those popular fronts. Whittaker Chambers, James Burnam, Frank Meyer, and Max Eastman were just a few of these one-time prominent or important Communists, and they all would eventually publish broadsides against the stultifying conformity of the left.

Refusing to tell the truth—or hear it—for the expediency of the cause was ethically, morally, and intellectually corrupting. Witness, the title of Chambers’ canonical memoir, reviled the sorts of people who “substituted the habit of delusion for reality.” Such people “became hysterical whenever the root of their delusion was touched, and reacted with a violence that completely belied the openness of mind which they prescribed for others.” He called this delusion “the Popular Front mind.”

The New Right suffers from—and tries to enforce—something similar. Call it the Populist Front.

When it suits their purposes, the Populist Fronters use the language of a “big tent” to advance Donald Trump’s policy agenda, demanding, whining, and inveighing as the moment requires to keep traditional Republicans and conservatives on board. But when traditional Republicans and conservatives push for their preferred agenda, the language changes to talk of “betrayal” by “elites,” “globalists,” “neoconservatives,” “RINOs,” and “never Trumpers.” Criticizing Trump or his imitators invites invocations of Ronald Reagan’s “11th Commandment”: “Thou shalt not speak ill of any fellow Republican.” But no insult is too vile for Republicans who criticize or oppose Trump.

The New Right’s Populist Frontism is easier to recognize if you distinguish fusionist conservatism from the “New Right” or “right-wing populism.” Neither temperamental nor “Reaganite” ideological conservatism are meaningfully populist in their philosophical commitments. Sure, every politician will claim that “the people” are with them. But a principled conservative would not subscribe to the view pithily (and probably apocryphally) attributed to Alexandre Auguste Ledru-Rollin: “There go the people. I must follow them, for I am their leader.”

The New Right’s approach to politics is primarily performative. It’s fan service for the customer base who want daily—or hourly—“wins” in the culture war. Trump’s approach to the presidency is uniquely suited to this style of politics, given that he sees the presidency like he’s both the producer and star of a reality show. Even when he engages in public policy, the headline is more important than the substance. He issues executive orders that don’t change the actual law or even substantively change more deeply ingrained regulations, but they do generate press releases and outrage from his enemies. The Populist Front’s very online enforcers of conformity are more interested in policing a narrative than actual policy.

There are serious, by all accounts decent, New Righters seeking substantive and well-intentioned (albeit often wrong) changes, on trade, industrial policy, and foreign affairs. On the “alt-right” fringe there are serious and committed racists and anti-Semites sincerely seeking to “create a Jew-free, White ethnostate in North America.” And there are factions all along the spectrum of alt-right who simply like to cosplay radicalism online or in real life. But what unites them all is an open and honest desire to replace the existing right and to redefine what it means be conservative. The New Right says they are engaged in a project of “rethinking” or “reinventing” what it means to be conservative. To adapt a phrase from Maya Angelou, when people tell you who they are, believe them.

The motto for the New Righters associated with the Heritage Foundation, the Claremont Institute, and various “America First” outfits and platforms is some variant of the rhetorical question “Do you know what time it is?” According to the writer David Reaboi, who is often credited with coining the phrase: “Knowing ‘what time it is’ is realizing that these institutions are crumbling, with or without you, and the surest way to get to something better is to allow them to crumble—and for as many people as possible to recognize that these things are, indeed, crumbling.”

This sort of argument, often attributed to Vladimir Lenin, used to be known as “the worse, the better.” Whether Reaboi considers himself a Leninist, I don’t know (or much care). But Steve Bannon, a major figure on the New—or populist, or MAGA, or nationalist—Right has proudly declared, “I am a Leninist.”

In this context, right-wing or “the right” becomes a Popular Front cudgel for policing acceptable ideas. Today’s “right,” we are told, loves tariffs, and the more the better. Therefore, you are not on, or welcome in, “the right” if you question their utility. And, thanks to our asinine political typology, if you are not on the right, you must be on the left. The same technique is used to protect and defend Trump more broadly. The left rejects Trump and Trumpism. Hence, through the alchemy of the fallacies of No True Scotsman and the excluded middle, you are transmogrified into a member of the left.

Knowing what time it is, is a form of apocalyptic politics. Like the “Flight 93 Election” argument from 2016, and countless variations of it, this worldview posits that the left poses an existential threat to American society, and therefore the right has not only a justification, but an obligation, to fight the left by any means necessary. The conservatives—temperamental and ideological—who see this sort of permission structure as destructive to norms, institutions, and conservatism itself are deemed to be unmanly and weak.

This turn was long in coming, but it began in earnest about a decade ago partly in rebellion against Obama and his designated successor Hillary Clinton, and in earnest with candidacy of Donald Trump who was deemed the perfect vessel to mount an insurgency against the conservative establishment. The atmosphere at the time was a bit like an allegorical merging of Invasion of the Body Snatchers and The Crucible. It now suffuses the Populist Front. For instance, Kurt Schlichter, a belligerently loud and paranoid columnist for Townhall, recently took his “side” to task, presumably for criticizing the Trump administration’s embarrassing “Signalgate” scandal. “Stop policing our own side,” he posted on X. “I know that gets you off and you feel great because you think it demonstrates integrity. All it demonstrates is weakness. Never ever help the enemy who wants you dead or enslaved. To do otherwise betrays a fundamental misunderstanding of the struggle we are in.” Save for the juvenile reference to “getting off,” this is the language—and thought—of an American Stalinist writing for The Daily Worker in the 1930s. As I mentioned earlier, for the radical, the seduction of fighting as a means to an end can turn into the permanent glorification of those means.

Right from the beginning.

Historically, ideological conservatism has been correctly understood as a subset of the right. But temperamental or dispositional conservatism need not be expressly right-wing. There are many people on the center-left who are meaningfully conservative in their outlook, even if they are not committed to the goals of ideological conservatism—beyond a general commitment to classical liberal precepts. Jonathan Rauch, Jonathan Haidt, William Galston, Stephen Pinker, David Brooks, Thomas Chatterton Williams, Jesse Singal, John McWhorter, Yascha Mounk, and Cass Sunstein are just a few of the intellectuals who nod along to Chesterton’s warning about tearing down fences willy-nilly.

But what is the “right”?

As most people interested in this stuff know, the categories of right and left as descriptors of the political or ideological spectrum were born in the French National Assembly in 1789. Delegates hostile to the revolution sat to the right. The more hostile, the further right you sat. Baron de Gauville, a royalist deputy in the Assembly recounted in his diary how the self-sorting of seating happened organically: “We began to recognize each other: those who were loyal to religion and the king took up positions to the right of the chair so as to avoid the shouts, oaths, and indecencies that enjoyed free rein in the opposing camp.” This practice eventually spread throughout much of Europe, and to America by way of the Soviet Union. (For an illuminating exploration of this migration, see The Myth of Left and Right: How the Political Spectrum Misleads and Harms America by Verlan and Hyrum Lewis).

The central question, now, is whether right-wing populism can be described as “conservative” in either the intellectual or temperamental sense. It seems to me the answer is, emphatically, no.

The debate over whether Trumpism is fascist tends to muddy more than it clarifies. But the comparison can be helpful in two ways. First, the Nazi seizure of power depended on the logic of the united front. The National Socialists were populist rabble rousers in the eyes of traditional German conservatives and aristocrats. But they were useful in the fight against the Communist left. The Nazis were adept at convincing the conservatives they were valuable members of their coalition, until the opportunity to marginalize those conservatives and seize power made that ruse unnecessary. The Nazis, in other words, were the alt-right of Germany, playing footsie with the traditional right until they could replace it.

Second, for nearly a century, fascism has been described as “right-wing”—starting with the Bolsheviks who believed it was “right-wing socialism.” Over time, the word “socialism” disappeared and fascism came to define “right-wing.” Whatever you think of the merits of that label, the fact remains that fascism was never meaningfully conservative. Contemptuous of classical liberalism, traditional morality, and orthodox Christianity, fascism was nonetheless called conservative for two reasons: because “conservative” and “right-wing” are conventionally considered synonymous and because the left opposed both. Conservatives have been stuck with association with fascism ever since.

This lexicological pas de deux is not reserved for arguments about fascism. What the left-wing hates is dubbed “right-wing” and what the “right-wing” hates is called left-wing. Today, Trump’s critics are called left-wing because they are his critics, even when they criticize him from the right. This is not new in American politics, FDR’s enemies were often labeled as “rightwing” even when they attacked him from the left.

But just because people use a term inaccurately, cynically, or promiscuously doesn’t mean the term has no meaning. The distinction between “conservative” and “right-wing” is not a new one. When William F. Buckley Jr. famously “excommunicated” antisemites and Birchers from the ranks of the respectable right, he made little effort to argue they weren’t “right-wing”; the key point was that they were not respectable, they were radical, irresponsible, and they undermined the credibility of conservatism. He didn’t want them in his coalition, even though they were “right-wing.” A decade earlier, many conservatives made the same argument about the threat from Joseph McCarthy and his populist and paranoid rabble-rousing. Chambers once wrote to Buckley that McCarthy was a “Godsend” for the left.

Today, it is worth asking if Donald Trump has been a similar godsend for the left.

If you wanted to destroy traditional conservatism—either ideological fusionism or temperamental—you could not design a better instrument than Trump.

Populist and nationalist economics have always been conducive to statism. There is nothing inconsistent between Steve Bannon’s “Leninism” and his desire for a new New Deal—the goal of American progressives since the first one. The whole point of populism is special pleading for a special group and statist intervention on their behalf. Trump has turned the GOP into a statist party, committed to industrial policy and protectionism. Nationalism invariably puts the state at the center of all political enterprises because the state is the instrument of national will. Moreover, nationalism is bound up in the romantic notion of a Leader who is the arbiter of that national will. On trade alone, in just a few years, Trump has moved the party closer to Dick Gephardt, Bernie Sanders, and William Jennings Bryan (though in fairness to the Great Commoner, Bryan was far more of a coherent free trader than Trump), than Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher.

If you wanted to destroy traditional conservatism—either ideological fusionism or temperamental—you could not design a better instrument than Trump.

On foreign policy, right-wingers today heap scorn on an America-led international order and on any notion that we should honor our alliances. NATO, the international trading order, even our border with Canada, are Chestertonian fences to be torn down for the simple reason the president of the United States cannot grasp why anyone built them in the first place and is invincibly immune to explanations for their continued existence.

For decades, opposition to abortion was a fundamental litmus test for membership on the right. Whether this was the correct position can be debated elsewhere, but it is an obvious fact that the left wanted the right to give up its commitment to the pro-life cause. Trump did more to get the right to do that than all of the efforts of Planned Parenthood and NARAL combined. Obviously, the GOP is not as maximalist on abortion rights as the Democratic Party, but Trump has simply abandoned the issue on fundamentally pro-choice terms. He opposes new federal prohibitions on abortion, favors over-the-counter sales of abortifacients, and has spoken against state bans on abortion after six weeks of gestation. Progressives in 2015 would see all these as triumphs.

If there is any idea more central to American conservatism than adherence to the rule of law and fidelity to the Constitution, I struggle to think of what it might be. And the Trump administration, on a near-daily basis, signals its contempt for both. The rule of law is being replaced by the Benavides rule: “For my friends, everything; for my enemies, the law.” For nearly a century, and in earnest since the 1970s, the conservative legal movement declared war on the idea of the “living Constitution,” the idea that whatever society needs should be considered constitutional. The conservatives won that battle, as even progressive judges and justices, often feel the need to engage in originalist arguments. As Justice Elena Kagan said in her confirmation hearings, “We’re all originalists now.” In response, the New Right now champions “common good constitutionalism,” which is just New Right speak for a living Constitution, albeit sometimes with a Catholic or Christian flavor. Common good constitutionalism was a joke to the conservative legal movement a few years ago. It is now an open source of debate and an exciting idea to many young lawyers and law students. Of course, Donald Trump himself surely has no idea what common good constitutionalism is, but as he defines the common good as whatever is good for Trump, he probably has an intuitive grasp of it.

Many of these and other changes made possible by Trump and his New Right defenders, if carefully and prudently implemented, might have been acceptable by some temperamental conservatives of the Kirkian tradition. Indeed, Trump has his defenders in such corners of the intellectual right. But what these sincere traditionalists have often fail to grapple with, in their efforts to put the best light on Trumpism, are the cultural transformations of the right that have come with the Populist Front. The subtitle of Michael Anton’s “Flight 93 Election” essay was “The election of 2016 will test whether virtù remains in the core of the American nation.” Nearly a decade later, do we see much of a renaissance of virtue on the American right? I see an explosion of anti-Semitism, paranoia, deliberate crudity, and the toleration and occasionally celebration of sexual decadence.

It’s of little use to focus on Trump’s own views because they are not, strictly speaking, ideological. He has a bookless understanding of politics, economics, foreign policy, and for that matter, religion. (When pressed for his favorite biblical passage, he said “an eye for an eye.”) But it is precisely because Trump is devoid of a coherent ideological or intellectual framework that once marginal factions on the right—and a few on the left—have gained political legitimacy by attaching themselves, remora-like, to his presidency. Some traditionally conservative institutions—the Heritage Foundation and CPAC the most obvious—have dumped traditional conservatism like so much ballast to align with the president. But the real shock troops of MAGA are populist “influencers” and organizations with little history or integrity to jettison in the first place.

The cultural commitments of these groups are not merely McCarthyite in their approach to politics; they are sybaritic and decadent in ways that would have made the crapulent McCarthy blush. Many on the right lionize Andrew Tate, an antisemite and a proud abuser of women. Matt Gaetz, an alleged drug abuser and, at least according to House investigators, an aficionado of underage prostitutes, was Trump’s first pick to run the Department of Justice. Sen. John Tower was denied confirmation as secretary of defense in 1989 because of his drunken “womanizing”; Pete Hegseth overturned that precedent. It wasn’t long ago that Bill Clinton’s dalliances with an intern were such an indictment of his character that conservatives agreed he should be removed from office. Donald Trump’s Caligulan sexual history is now proof of his manliness.

Indeed, manliness is such an obsession of this New Right that it is invoked to justify a bizarre suite of opinions and policies. We need tariffs to bring manufacturing home and, with it, “manly” jobs. Why? Because, as Fox News’ Jesse Watters puts it, “sitting behind a screen all day makes you a woman.” (Watters also believes that real men don’t drink milkshakes or use straws). Glenn Beck was once a Trump critic, but like most talk-radio conservatives, he eventually caved to the populism of his audience. He believes that Trump’s success is attributable to the fact that he’s a male role model. “There are no examples of men being men. James Bond. That’s it. A movie.” But Donald Trump is “a guy who marries a supermodel, is like, ‘Yeah, I can make it with any model I want.’ He’s over the top, but he fights back, he doesn’t flinch … he is the almost cartoon of an alpha dog. You know what I mean? And I think because we have taken alpha dogs and shot them all, when he comes to the table there’s a lot of guys that are out there goin’ ‘Damn right!’”

Putting aside the strangeness of claiming that all of these James Bondian alpha dogs allowed themselves to be euthanized, the sadness of this judgment is twofold: It lacks any pretense at moral judgment and there’s a grain of truth to it. There is a Nietzschean nihilism to MAGA culture. This is the leitmotif of so much of Trump’s foreign and domestic policy and his politics of retribution. Of course, we should make a profit from a raped and ravaged Ukraine. Of course we should take Greenland or Canada—because that is what alpha dog countries do when they have alpha dog leaders. And it is being emulated by a whole generation of self-described conservatives who believe punishing your enemies is superior to persuading them, that attention gained by crudeness or lies is better than respect for integrity. It is reminiscent of Edmund Burke’s lament that the habits of empire in India were turning young Englishmen into “birds of prey.” They “drink the intoxicating draught of authority and dominion before their heads are able to bear it, and as they are full grown in fortune long before they are ripe in principle.” The unqualified young loyalists filling the ranks of the GOP in the White House and Congress, as well as a generation of social media-addicted influencers, crypto bros, cable news choristers, and campus warriors, look at the culture that rewards their meanness and crassness and think things are as they should be. Strength is seen as a good in itself, untethered to ideals of honor or virtue.

Russell Kirk would surely cheer the shuttering of DEI programs at college campuses (as I do), but he would look upon the right-wing campus warriors and podcast bigots who make rudeness and crassness a virtue and weep. Kirk believed that “the moral imagination aspires to the apprehending of right order in the soul and right order in the commonwealth. It was the gift and the obsession of Plato and Virgil and Dante.” It’s doubtful the MAGA jabroneys whoring for clicks even know—or care—who Plato, Virgil, or Dante were. “It is no exaggeration to suggest that the idea of the gentleman stands as the lynchpin of Russell Kirk’s entire social theory,” writes Ben Reinhard. “Well-educated, well-read, and virtuous, the gentleman stands as the living link between the present and the past; in many ways, he is the moral imagination embodied.”

The new Populist Front is contemptuous of any moral imagination that cannot be weaponized against its enemies—but rarely and only selectively applied to its friends. This is what populism and nationalism lead to when untethered to any limiting principle other than the pursuit of power. It is the logic of the ubermensch absent any respect for gentlemanliness, nationalism bereft of national honor; populism for our people, and our people alone. As Donald Trump once said, “The only important thing is the unification of the people—because the other people don’t mean anything.”

If, thanks to the poverty of our political vocabulary, we must call this right-wing, so be it. But, please, don’t call it conservative.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.