Once a hallmark of the modern American presidency, the weekly address—those Quibi-length presidential pep talks—disappeared over the last two administrations. Donald Trump killed it off in 2018 and, after a short revival by Joe Biden, the broadcast no longer exists in any form.

For understandable reasons. As news cycles churn faster than a president can type “covfefe,” weekly recaps can feel pointless. But seeing how successful presidents have engaged with the public underscores why it’d be wise to revamp the weekly address.

It’s been nearly a century since Franklin Roosevelt delivered fireside chats during the Great Depression. While many look back on those talks as marking the birth of the weekly address, Roosevelt only hosted 31 chats during his 11 years in office. His first address came in the wake of a national emergency—the closing of the banks—just days after his inauguration. (FDR reportedly didn’t even like the term “fireside chats,” which was coined by CBS News Washington bureau chief Henry Butcher.)

Ronald Reagan, who had delivered daily radio commentary on weekdays after leaving the California governorship, began hosting weekly addresses in 1982. By the end of his presidency, he had delivered 331 broadcasts. “He had an extraordinarily good voice and the White House realized that they were missing one of their resources in Reagan himself by not going on the radio,” Reagan biographer Craig Shirley told me. Throughout the 1980s, talk radio spiked in popularity. Radio sales grew by nearly 50 percent from the start of the decade to 1988, the last full year of Reagan’s presidency.

Reagan had mastered the medium of his time, just as great presidents before him had mastered theirs. Thomas Jefferson brilliantly used partisan newspapers, secretly starting an outlet to attack his rival Alexander Hamilton. Abraham Lincoln understood the power of published speeches—crafting them not only for listeners, but also for newspaper readers, knowing his addresses’ texts would be printed. And John F. Kennedy recognized television’s unique ability to connect with voters. He was the first president to conduct live press briefings on television, holding 64 news conferences over the course of his presidency. They averaged 18 million viewers.

President Joe Biden attempted his own rebranding of the weekly address, releasing “A Weekly Conversation” for a few months. The segment featured highly edited chats with everyone from Barack Obama to a hardware store owner. But these choreographed and overly staged videos never caught on. That’s a loss not just for the weekly address tradition, but for citizens today.

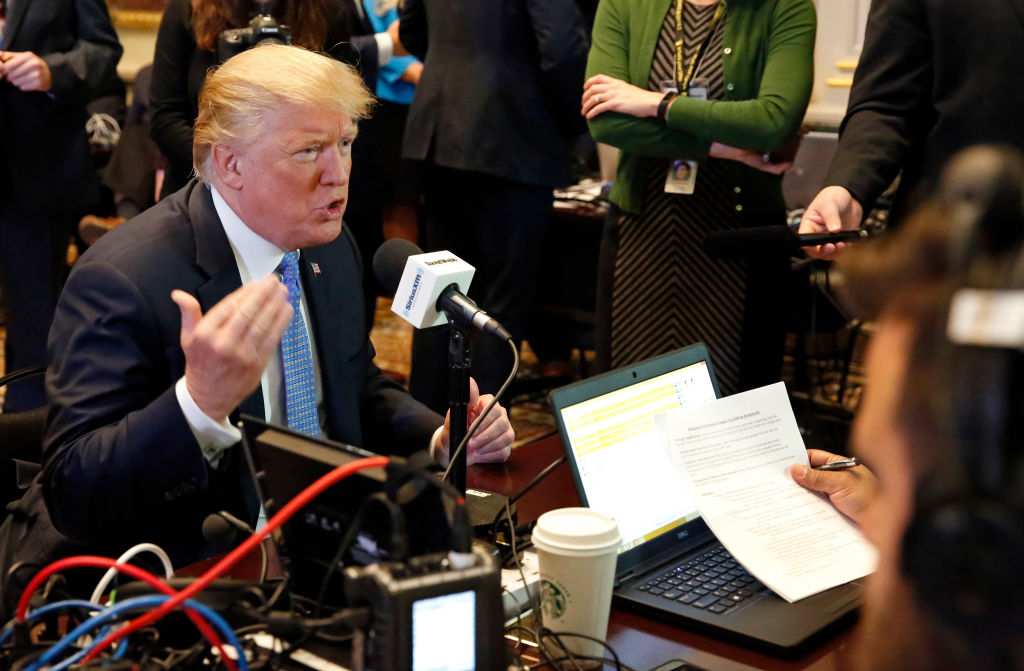

After a presidency marked by evasiveness—most notably by Biden’s retreat from the public view—a regular dialogue with the American people would be welcomed by the country. People want to be led, and when a sitting president is out of sight, citizens begin to turn elsewhere. Trump has filled the leadership void from the bully pulpit of Mar-a-Lago—no Oval Office necessary—but it’s largely transpired through Truth Social. He has only given one news conference since winning the election. And there’s evidence his administration might not be keen on briefings: The Trump White House set the record for the longest span without a formal, on-camera press briefing, lasting over 300 days. It’s unlikely Trump wants to regularly engage with traditional media outlets he’s both sued and slapped as “the enemy of the people.”

So if Trump and his team are going to avoid briefing the press, then reinventing the weekly address might be the next best thing.

Today, there are very few media moments Americans consume together. Axios’ Jim VandeHei and Mike Allen call it the “shards of glass” news era—audiences splintered into thousands of little pockets. That means not only fewer shared moments but also fewer shared truths. And while previous incarnations of the weekly address had the cultural cachet of a C-SPAN 2 show, a reimagination could re-engage numerous constituencies.

This revamped address would likely be very different from those of the past. Many have suggested welcoming podcasters into the White House briefing room. Why not invite them to interview Trump and release those conversations as the new weekly address?

Trump’s decision to flood the manosphere’s RSS feeds undoubtedly expanded the president-elect’s electoral base and helped win over undecideds, but he could think beyond Joe Rogan and Theo Von. However unlikely it is, he should walk into enemy territory: invite Kara Swisher and Scott Galloway of Pivot into the White House, podcast maestro Ezra Klein, and even On Brand host Donny Deutsch. These voices would bring different issues to the fore. And they’d allow Trump—always up for a fight—the opportunity to win over their audiences.

Even if Trump sticks with interviewers who mostly turn their microphones over to him, connecting with podcasters could help Trump avoid one of Biden’s biggest mistakes: his insularity. Just take inflation, which Biden dismissed in the eyes of voters even though it was the highest in decades. When I called up political strategist Bradley Tusk to discuss all-things-weekly-address, he pointed out the peril of presidents being holed up in the White House.

“I think what happens is you get lost in the fact that, A, you’re living a totally fantastical life,” Tusk said. “And, B, all of the people around you are so obsessed with their own little theories about what’s being said about them on Twitter that they’re forgetting that what happens inside the Beltway or MSNBC or wherever else has no impact on the world whatsoever.”

It’s not just about breaking free of 1600 Pennsylvania-itus. Barely any media property from the 1980s looks the same today. Authenticity is the most important currency. Which means the stale and stilted delivery is long overdue for a makeover.

YouTube revealed last month that its users watch more than 400 million hours of podcasts on living room devices every month. According to the Wall Street Journal, almost 100 million Americans regularly listen to podcasts. Bending toward that trend could very well fail, but it might also help Trump—and the presidency as an institution.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.