The Declaration of Independence is a loaded gun—like Chekhov’s rifle, you cannot just expect it to hang there on the wall without anybody ever trying to use it.

But ignore that document was precisely what the founding generation did—the Declaration looms large in our political imagination today, but Washington, Jefferson, et al., kept it at arm’s length. They declared their independence, they won it on the battlefield, and then they ... just stopped talking about it. You can see why: Having established a new republic, they wanted to keep the thing together as well as they could, and so it would have been no good to go around waving a manifesto for revolution that many of them had signed. There were more than enough insurrections as it was.

Ironically, it was Abraham Lincoln who leaned into the Declaration when confronted with slave-holding Southerners who believed that the time had come when it was “necessary for one people to dissolve the political bands which have connected them with another.” What Lincoln derived from the Declaration was not a writ for secession but a mandate for the fundamental principles, then as now imperfectly realized, of the American Revolution itself.

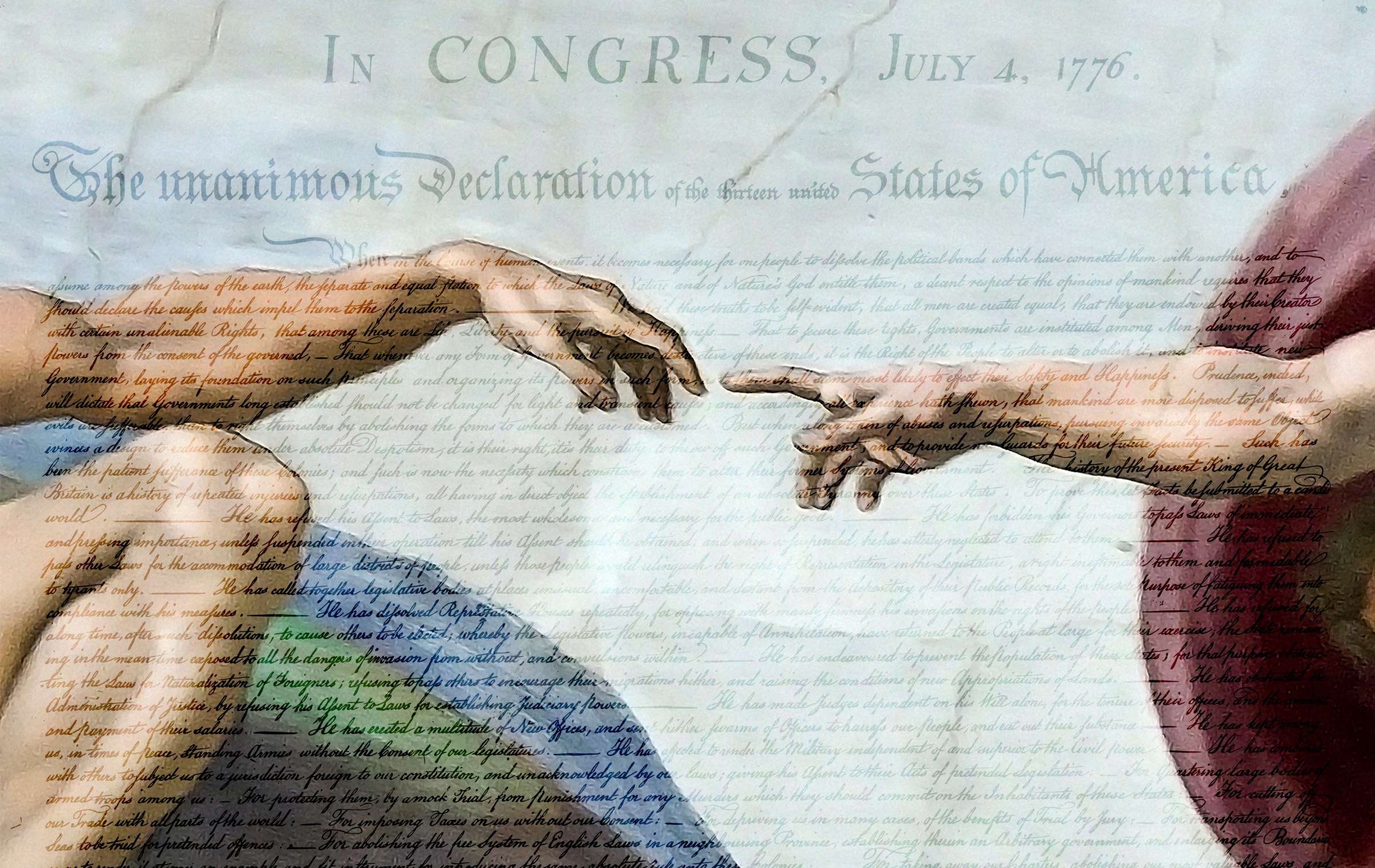

As Union soldiers marching into battle to the tune of “We Are Coming, Father Abra’am” surely appreciated, the 16th president, with his presagious Hebrew name, was a kind of patriarch (he dreamed of visiting Jerusalem in his retirement), and the Declaration of Independence that he took as his political scripture presents the American proposition as a theological statement: “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights, that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.”

We modern rationalists find much in those words that our secular sensibility can digest easily: legal equality, unalienable rights, consent. But those were not radical or revolutionary ideas: They were, at most, extensions of principles of English government that went back at least as far as the Magna Carta.

But the Declaration of Independence complicates and enriches—inestimably—those old English notions of equality, fundamental rights, and consent by associating them with its most radical claim, which is a matter of supernatural rather than natural law: that we must enjoy the dignity of citizens, rather than endure the servility of subjects, because we are “endowed by our Creator” with the capacity for higher things.

The Declaration is clear on the point: Liberty, rights, dignity, the opportunity to pursue our own happiness and prosperity in our own way—these are not gifts given by one man to another, no matter how powerful the one man or how subordinate the other. The king cannot bestow such gifts on us, because they are not the king’s to give—or to take away. These gifts are given to us by God, not in His role as Judge or Father or Redeemer (and there is no mistaking the Anglo-Protestant sensibility here) but in His capacity as Creator. We are not animals who have been simply given liberty to enjoy the way a stray dog might (or might not) be given a warm bed and a meal out of discretionary kindness—we were created for it. The enjoyment of liberty in which we discover the fullest sense of our humanity is not some happy addition tacked onto the divine plan–it is the point of the thing.

In an important sense, then, the Declaration of Independence is not only a brief against arbitrary tyranny—it is, if only in that one electric sentence, a sermon in minature against idolatry, one worthy of Jonathan Edwards: “Man will necessarily have something that he respects as his god. If man does not give his highest respect to the God that made him, there will be something else that has the possession of it. ... Enmity necessarily follows.” Why must enmity follow? “A man will be the greatest enemy to him who opposes him in what he chooses for his god: he will look on none as standing so much in his way as he that would deprive him of his god.”

And so here we are.

At enmity.

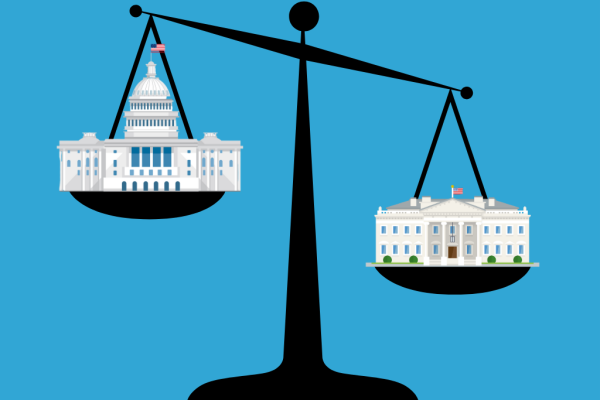

Our descent into political idolatry—into the effective if unacknowledged worship of the state, most often in the personal form of the president—seems to have been (I hope my Presbyterian friends will forgive me!) pre-ordained. A very intentional cult of George Washington was cultivated (cult is the first word in culture) from the beginning, and by the time the federal decorating committee got around to hiring former Vatican artist Constantino Brumidi to paint the interior of the Capitol dome in 1865, the Italian artist’s thoroughly pagan work—The Apotheosis of George Washington—was entirely of a piece with the regnant American theology. The commander in chief (the Latin word for the office is imperator, or emperor in English) of the American continental empire had quickly and quietly displaced the Creator of the Declaration of Independence—which is to say, the creature superseded, as a political matter, “the God that made him” at the center of our national life.

Like the man said: enmity.

Why should this matter to anybody but a few isolated religious fanatics?

As a former copy editor, I am inclined to check the markup history. As many of you will know, John Locke’s formula—“life, liberty, and property”—became the more familiar “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness” by means of Jefferson’s artful condensation of George Mason’s language: “All men are by nature equally free and independent and have certain inherent rights, of which, when they enter into a state of society, they cannot, by any compact, deprive or divest their posterity; namely, the enjoyment of life and liberty, with the means of acquiring and possessing property, and pursuing and obtaining happiness and safety.”

“If it is true that we are endowed by our Creator with the capacity for citizenship Jefferson described, then we are overdue for an era of penance and reconciliation in our national community life.”

Leo Strauss, that great reader between the lines, saw in this change evidence of an American mission: that these United States should not form a “mere alliance,” as Aristotle put it, but should instead constitute a genuine community directed at some higher good. Strauss argued that the republic announced in the Declaration of Independence was not meant to be concerned only with “making possible peaceable exchange and preventing everything which would endanger that peaceable exchange, such as fraud and force,” but was to be one that “sees its function in making the members virtuous, to use the old-fashioned expression.”

John Adams famously observed that our Constitution was fit only for a “moral and religious people,” and he was not being redundant—the underlying intellectual architecture is not only moral but rooted in a specifically religious idea about the relationship of man to “the God that made him.” The theological and specifically Protestant character of the American proposition need not exclude modern Americans (such as myself) who do not hew to the Reformation tradition any more than it excluded the religiously unorthodox Thomas Jefferson, who wrote the very words here at issue. But one cannot honor the spirit of the document without taking seriously what it actually says and what it actually means.

And what it means—if we take it seriously—is no less revolutionary today than it was in 1776. If it is true that we are endowed by our Creator with the capacity for citizenship Jefferson described, then we are overdue for an era of penance and reconciliation in our national community life. This will be painful for Americans, because in our political life we have—there is no painless way to say it—a great deal of which to be ashamed.

An America in which Americans took the American proposition seriously would be a very different America, and a better one. Yes, render unto Caesar what is Caesar’s—of course.

But nothing more. Not one mite. Not without a fight.

“We hold these truths,” the Declaration says. So, let us hold them tight. And let the demagogues thunder and strut, and let the tanks roll through the streets of Washington if the idol of the age demands it. We have a fearsome weapon hanging on the wall, one whose thunder is louder than that of any artillery, the real and true “shot heard ’round the world.”

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.