TALLAHASSEE—In the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic, a Republican lobbyist was on the telephone with Gov. Ron DeSantis discussing his controversial decision to open hundreds of miles of Florida beaches even as the coronavirus spread throughout the United States. The press was skewering DeSantis; political opponents were calling him “DeathSantis.” The lobbyist was worried.

Politically, the governor was on thin ice. At this initial stage of the outbreak, scientists and doctors were struggling to fully understand COVID-19. Even President Donald Trump was counseling Americans to stay home. Yet after DeSantis pored over data and consulted experts with a range of views about lockdowns, he concluded the virus would spread through the population regardless. Closing businesses and turning away tourists would only delay the inevitable—and destroy Florida’s economy in the process.

The lobbyist, a DeSantis ally, recalled asking the governor during the call if he was sure he had made the right choice.

“And I remember what he said to me—I’ll never forget it because it bore out to be true, but he said: ‘I don’t care what they say about me right now, I care about what they say about me six months from now,’” this Republican said. “He believed his reading of the data and his way of handling COVID was the right thing before anybody else did, and stuck with it regardless of the hits.”

Veteran Republican insiders in Florida’s capital who have worked closely with DeSantis describe an active, disciplined leader who is supremely confident in his own judgment, does his homework and relishes making decisions. Yet for all of his conviction as an executive and recent success at the ballot box, doubts aplenty about DeSantis’ ability to navigate the campaign trail exist among the Florida lobbyists, political operatives and elected officials who spoke to The Dispatch for this story. Both sides of DeSantis will play a pivotal role in determining the course of his likely presidential campaign.

Whether providing positive or negative assessments of DeSantis, most Republican insiders in Tallahassee would only speak to The Dispatch if granted anonymity, given the governor’s dislike of leaks or gossip. “There’s no questions asked; you’re just done,” the lobbyist supportive of DeSantis explained.

‘That’s going to be a real problem for him.’

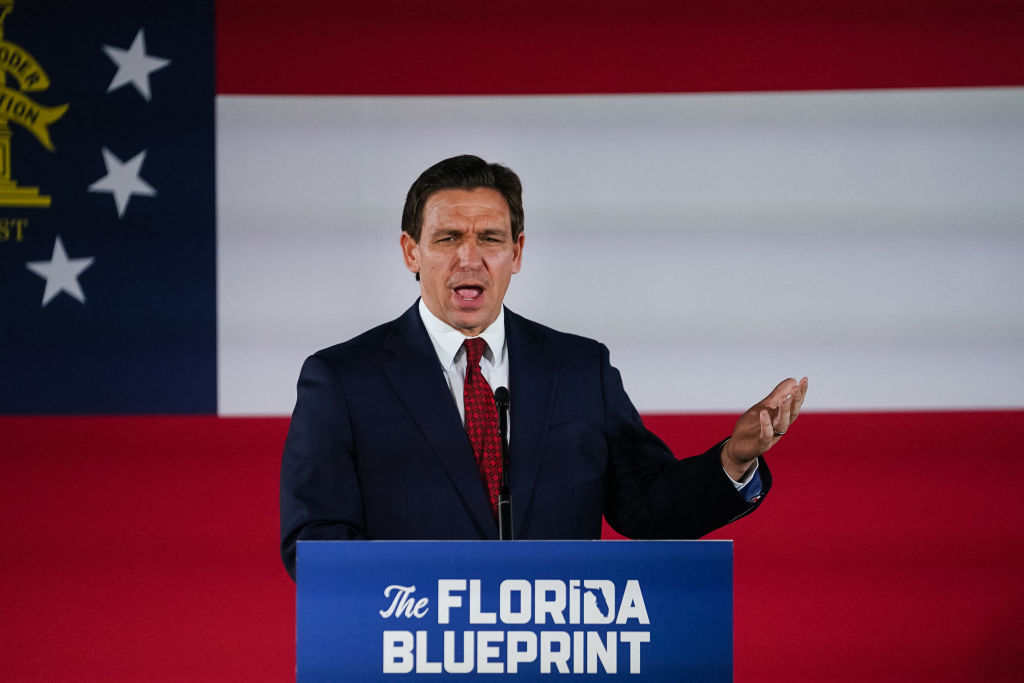

DeSantis, 44, assumed office in 2019 as a relatively young and inexperienced chief executive with few connections in Tallahassee.

He had three terms in the House of Representatives under his belt, representing a northeastern Florida district anchored in suburban Jacksonville. That’s a relatively thin resume compared to his most recent predecessors. Sen. Rick Scott, a Republican who moved into the governor’s mansion in 2011 at 58, had managed a hospital conglomerate. And his predecessor, then-Republican Charlie Crist, won in 2006 at age 50 after four years as Florida attorney general.

That DeSantis was elected at all in 2018 was a stroke of luck. Adam Putnam, then the Florida agriculture commissioner, had a huge financial advantage and was the undisputed frontrunner until Trump endorsed his younger rival. In November, amid a midterm election backlash against the 45th president, DeSantis barely won, beating Democrat Andrew Gillum by 32,463 votes out of 8.1 million cast.

In the early days of his administration, DeSantis showed some hesitation that seemed to reflect how close the race had been. “I don’t think he came in with a plan in place as to how he was going to govern,” a Republican who previously served in the legislature said. But in time, that changed. “He transformed in the governor’s mansion,” the former legislator said.

DeSantis ultimately impressed a lot of the old political and policy hands in Tallahassee who made their living as far back as Lawton Chiles, Jeb Bush’s predecessor and the last Democrat to occupy the governor’s mansion. DeSantis was not just smart, they concluded, but especially so. Regardless of whether they were personally fond of DeSantis or supportive of his presumed 2024 bid, they all know the governor as a quick study who synthesizes vast quantities of information into detailed policy proposals, accessing supporting data on command to make a strong case to aides, lawmakers and lobbyists.

“When you walk into DeSantis’ office, his desk is covered in [papers] because he does all of his own due diligence,” a Republican official said. In his first term that included intricate COVID-19 data provided by the federal government along with academic or technical studies. “It’s not as bad as it used to be,” this Republican added, of the governor’s desk, suspecting someone must have told him it needs to look presentable for guests. “But I’m a big believer—DeSantis does his own research.”

DeSantis’ staff credits his decisiveness for Florida’s economic and demographic success in recent years. “We have refused to use polls and to put our finger in the wind,” deputy press secretary Jeremy Redfern said. “Leaders do not follow, they lead.”

“Throughout the governor’s first term, he chose a path deemed unpopular by the establishment; he pushed back against the prevailing narrative because it was the right thing to do,” Redfern added. Others see this as a liability.

One GOP operative observed, “If you’re in agreement with him, he’ll sit and talk and be your pal. But he does not suffer—not fools gladly—but those who disagree.” This isn’t much of a liability in Tallahassee, where Republican legislative supermajorities and a deep well of political capital make DeSantis virtually untouchable. But his stubbornness, and who he surrounds himself with, could become major liabilities on the national stage.

“He likes sycophants, people that tell him: ‘Yes sir,’” the GOP operative said. “That’s going to be a real problem for him.”

The dynamic that could undo him nationally is currently helping him lay the groundwork for a more convincing presidential campaign. Nearly three months into his second four-year term, DeSantis is in complete control of the agenda in the state capitol.

The governor has called the legislature into special session twice this year already, and has lawmakers working on dozens of personal priorities. Laws he signs affecting pandemic policy and public education make national headlines. But in Florida, Republicans marvel at accomplishments like tort reform. For years, the trial lawyer lobby succeeded in derailing legislation, even with Republicans in power. This year, under DeSantis, legislation passed the state House of Representatives and the state Senate in just weeks. He signed it into law in late March.

Meanwhile, the legislature also is poised to pass legislation changing Florida’s “resign to run” law, so that DeSantis would not have to exit the governor’s mansion if he won the Republican nomination.

One Republican lobbyist (“not a DeSantis cheerleader”), called the governor “bright” and praised his “uncanny policy acumen.” What won over this skeptic was the governor’s handling of his high-profile dispute with Disney over the firm’s criticism of the Parental Rights in Education Act, referred to by opponents as the “Don’t Say Gay” law.

When DeSantis first threatened to retaliate by altering tax and regulatory breaks Disney enjoyed for decades, this Republican lobbyist cringed. Through the Walt Disney World resort, Disney employs tens of thousands of Floridians and generates billions of dollars in tourism revenue for the state. Fighting with “the mouse,” seemed risky. But not only was DeSantis undeterred, he predicted, accurately, exactly how the row would play out.

“When Disney happened, DeSantis was telling me he just talked to the CEO and he was telling him: ‘Don’t do this.’ And the CEO is calling him, saying, ‘Look, I have to do this.’ And he said: ‘Don’t do this, I’m going to have to beat you up,’” this lobbyist said, recalling a conversation with the governor. “He said: ‘I’m going to fight and my numbers are going to go [up].’ … This was a year before it happened. And then you could kind of see him take off.”

Now, it looks like DeSantis’ fight with Disney might not be over after all. Before relinquishing power to regulators appointed by the governor under a new state law stripping Disney of its autonomy, the company used its outgoing authority to hamstring Florida from exercising future oversight it might find objectionable. The governor’s critics claim Disney outsmarted him. DeSantis and his supporters say otherwise. “Rest assured — you ain’t seen nothing yet,” he said Thursday,” according to CNN.

Does DeSantis like people?

Florida, the third most populous state in the union, has long been politically competitive.

It boasts unique cultural and ethnic diversity while young suburban families and elderly retirees remain important voting blocs in the state. It contains major urban cores as well as vast stretches of rural land and nature preserves. Active pockets of modern, Democratic progressivism can be found throughout, along with growing communities of “MAGA” conservatives. Florida is even divided into the Central and Eastern time zones.

This is the state DeSantis won statewide twice—the second time with a nearly 20-point margin of victory. In the process, the governor swept his party into power nearly everywhere that mattered, turning Florida a shade of red and ending, for the time being, its status as a perennial swing state whose 28 Electoral College votes decide presidential elections.

“Ron DeSantis put a dagger in the heart of the Florida Democratic Party,” said state Sen. Blaise Ingoglia, a former Florida GOP chairman. “They are flatlined; they cannot recover.”

Yet, for all his political success in Florida, doubts linger about the governor’s chops as a campaigner. Many GOP operatives in Florida are skeptical he can meet the challenges of a presidential bid, with its endless demands and unrelenting pressure.

One common question in Florida political circles: Does DeSantis like people? Or, put another way, is he willing to subject himself to the rigors of retail politicking so important to a presidential bid, particularly in the key early primary states? It’s not just the diner drop-ins and munching on fried food at the state fair. It’s hanging out for selfies and chatting up voters at a campaign stop for an hour-plus after the official event ends.

Many Republicans here who have observed DeSantis through two statewide bids have some version of the following story: The governor is hosting or headlining an event and is expected to mingle with attendees at some point. Instead, DeSantis does the bare minimum—delivering his remarks and immediately heading for the exit.

A Republican former legislator recalled one such event, at the governor’s mansion, early in DeSantis’ first term. “Typically, a governor will welcome everybody to the mansion, work the crowd and will be there till the end. In this instance, he welcomed everybody and went upstairs and he was gone,” this party insider said.

“No f—ing way,” said the Republican lobbyist who lauded DeSantis on Disney, when asked to imagine the governor submitting to meet-and-greets with voters after taking questions from them during a town hall meeting. “That’s just part of who he is. Whatever walls are there, they’re there.”

“DeSantis is not relationship focused,” one DeSantis partisan acknowledged. “If he believes in something, then he’s going to get from A to B as efficiently and as quickly as he can—and he’s not going to get there by schmoozing.” In the executive office, DeSantis is similarly all-business. “He doesn’t talk about family stuff,” one Republican said. “He’s not really a chit-chatter.”

For every question surrounding the governor’s political viability, the answer seems to be his wife, Casey DeSantis. Republicans here say she compensates for shortcomings that could prove fatal in a 2024 presidential contest.

Married 14 years at the end of September, the couple has three young children. (On the weekends, when the governor’s schedule allows, it’s not uncommon to find him at the golf course with son Mason, 4, who apparently has quite the swing for a boy his age.)

There’s no adviser DeSantis trusts more than the Florida first lady, a 42-year-old former television journalist and news anchor. “Casey DeSantis is a star,” said the GOP operative who griped that the governor does not brook dissent. “She is a tremendous asset.” She also has tremendous power inside DeSantis’ political operation. “If you do not please Casey, you do not last long.”

Ron readies his run.

Desantis is expected to announce for the White House as early as May, after Florida’s current legislative session expires.

In the interim, his presidential-campaign-in-waiting appears to be staffing up. But Team DeSantis is keeping information close, declining to elaborate on launch timing or where the campaign would be headquartered. The governor’s political team is even refusing to say whether the pro-DeSantis super PAC, Never Back Down, is in fact his designated big-money outside group. (Never Back Down, led by Republican strategist Jeff Roe, has been on a hiring spree, attracting attention for signing former Trump 2020 operatives.)

The other question Team DeSantis would not answer was whether his presumed presidential campaign would hire a pollster. The governor loves to brag he doesn’t employ pollsters, nor does rely on survey data or focus groups to inform policy development or political strategy and messaging. Indeed, he has a rather low regard for political consultants in general, seeing them as overpaid for the actual value they bring.

Relying on a tight circle of advisers dominated by him and his wife worked for his congressional and gubernatorial bids. But those campaigns unfolded on his home turf, in controllable environments. A presidential bid is less predictable, spanning multiple states, with separate teams operating in unfamiliar territory while the candidate and senior campaign leadership are necessarily elsewhere. Micromanaging a campaign runs the risk of limiting how much the DeSantis machine could scale up.

Other Republicans said they suspect DeSantis will let go of the reins—reluctantly, out of necessity. “Well, he’ll have to,” one GOP supporter said. Added another: “His inner circle is a little bit too small right now. It may have to expand, but that will probably be a learning process. People are going to have to earn the governor’s trust.” A spokesman for DeSantis’ political team did not respond to a request for comment.

For at least three years, DeSantis has been at the forefront of issues the Republican base cares about most: Freedom from coronavirus restrictions, granting parents authority over public school curriculum, cracking down on liberal districts attorney, using state power to regulate progressive activism by big business, and spearheading changes to state election law, among others. Republicans looking forward to a DeSantis 2024 bid say the governor has a uniquely fine-tuned political compass, empowering him to understand what conservatives want, sometimes before they do.

There are lingering doubts, however, that DeSantis isn’t nimble enough to handle Trump’s asymmetrical attacks in the GOP primary, nor effectively adjust when confronted with challenges he cannot swat away by attacking Democrats or a hostile media.

Recently, the typically steadfast DeSantis ping-ponged from dismissing Russia’s invasion of Ukraine as a “territorial dispute” to claiming his comments were misconstrued and emphasizing the incursion was “wrong.” The governor also changed his tune on Trump’s indictment. At first, DeSantis limited his comments to criticizing Manhattan District Attorney Alvin Bragg for prosecutorial overreach but suggested Trump was in legal jeopardy because of his own mistakes. On Thursday, the governor said Florida would not assist New York in the former president’s extradition despite lacking constitutional authority to block it.

These issues are understandably delicate to manage, particularly considering DeSantis does not have an actual campaign up and running.

But some Republicans point to an exchange in last year’s gubernatorial debate with Charlie Crist as a red flag. At one point, Crist asked DeSantis if he planned to serve all four years of a second term if reelected, a topic he should have expected and prepared for. The governor eventually counter-punched, declaring “the only, worn out old donkey I’m looking to put out to pasture is Charlie Crist.” DeSantis initially hesitated, however, appearing on the screen as though he hoped to avoid answering a question.

Stating the obvious, Republicans note that primary debates with Trump, not to mention any general election faceoffs with Biden, are likely to have several moments more difficult and unpredictable than that. “It’ll be tough for him,” a GOP strategist said. “It’ll be hard.”

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.