The world—which may be personified with acceptable economy in Larry David writing for the New York Times—is very angry at Bill Maher for having had dinner with Donald Trump and then speaking about the president courteously.

Beyond the usual warning against the “politics of cooties,” I have way more to say about this than I probably should:

First: Maher isn’t exactly Robert Caro or Tom Wolfe, but comedians, like historians and journalists (and novelists and poets and some painters) are in the business of social observation. As such, a good deal of what goes into their work happens in the form and context of social life, of socializing—dinners and drinks and cocktail parties and all the rest of it. If you spend any time working as a journalist in New York City or Washington, you may develop a skill that is as useful for a columnist in 2025 as it was for William Makepeace Thackeray in 1847: the ability to go to a party and distinguish those who are engaged in recreation from those who are at work.* It isn’t always clear, which is a very good thing for journalists who pick up useful tips and tidbits later in the evening when the subjects have had a few drinks.

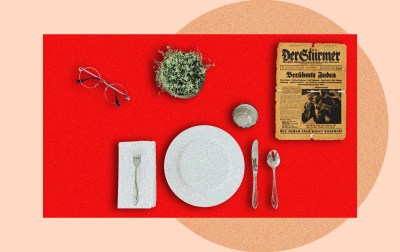

I do not think that I have left much room to doubt my opinion of Donald Trump, but I make liberal allowance for journalists and historians and even for comedians when it comes to meeting people and seeking out opportunities to interact with men and women who are in many cases far from admirable. Larry David lampooned Maher in a Times essay headlined “My Dinner with Adolf,” and it was pretty good—not great, but pretty good. (One does not go to the New York Times for big laughs.) But take the counterfactual seriously: How interesting would it have been if some interesting writer of the 1930s—say, Pearl S. Buck or Sinclair Lewis—actually had had a dinner with Adolf Hitler and documented it? Or if Charlie Chaplin had had the opportunity to interview Hitler rather than merely mock him from far? I would be interested to read such an account. If I could put Larry David in a time machine and have him have dinner with Hitler—who wouldn’t read what he wrote about it?

Second: But he didn’t have to be so nice about it, did he? That’s the extended complaint. And I don’t suppose he did. (I am aware that the implication here—that Maher is nicer than I’d be—doesn’t say very much.) We should keep in mind a couple of non-obvious things: One is that Maher and Trump are two men in the same business—entertainment—and there is a natural camaraderie at work.

More important is the fact—and I think Maher will disagree here, but he’s wrong—that Bill Maher and Donald Trump have the same politics. No, Maher doesn’t want to catapult every man, woman, and 2-year-old American citizen with a Hispanic surname over the border following a generally southern vector, but that is incidental. Maher, like almost all entertainers, is by nature a populist—a crowd-pleaser. Maher describes himself as a generally moderate centrist and thinks of himself as a practitioner of rationalist politics.

(The Oakeshottian overtone there is intentional, and I’d happily bet everything in my bank account vs. everything in Maher’s that he never has read Rationalism in Politics.)

For people such as Maher, the problem with politics seems to be that a relatively small group of fanatics at the extremes exercises disproportionate power over cowardly party leaders and the broader political apparatus, which naturally responds to those who put the most pressure on it, leaving the nice good sensible centrist people in thrall to partisans and ideological maniacs. Excluding a few insult artists such as Don Rickles, the comedian’s proposition to his audience is precisely the same as the populist demagogue’s: The problem isn’t us, the good, sensible people here in this room—it’s those other guys, out there. They’re the ones we’re laughing at.

“If Maher is guilty of something, it is of being so much a part of the same world as Trump that he is like one of those fish who doesn’t know that he is wet, and, for that reason, lacks the benefit of self-awareness and the consequent benefit of being able to maintain some critical distance—not from his subject but from his own reaction to his subject.”

“I’m not the leader of anything,” Maher says, “except maybe a contingent of centrist-minded people who think there’s got to be a better way of running this country than hating each other every minute.” Which is a nice sentiment, but centrism is not the answer you’re looking for when so much of what’s wrong with our politics comes from right there in the center. For example, Americans on average take about as dim a view of trade as Trump does—it is part of the reason they elected him—and what they object to in his recent performance is the ad-hocracy and the stink of incompetence, not the hostility to trade per se. The centrist view of immigration in the United States is closer to Trump than it is to the Wall Street Journal. Americans fiscal preferences are high spending, low taxes, and a balanced budget–i.e., entirely irrational.

Maher is wrong about the locus of our political problems—and, to the modest extent that he has serious views on the question, so is Trump. The American demos does not consist of a large majority of sensible centrists who are, for structural reasons, disempowered to the advantage of ideological extremists and self-interested operators who make their living out of manipulating the system. Those fanatics exist, and so do the cynics who milk them for profit and position, but the American political dynamic is not in fact very much like the one described by populists of either party or by the populists of the center.

The great deforming forces of our public life—conspiracy theories and the paranoid mentality that feeds on them, political tribalism, politics as a substitute for religion, politics as entertainment, politics as status competition, digitally enabled social isolation and the subsequent generalized anxiety typically expressed as rage and hysteria, the centrality of contempt and disgust in our political psychology—are problems of the left, problems of the right, and problems of the center, because they are problems of American life. The worst aspects of American policy right now—our precarious federal fiscal situation, our incoherent foreign policy—are direct results of politicians’ trying to satisfy voter preferences that are both widely held and wildly irrational.

Demagogues such as Donald Trump are both symptom and disease in this respect, and so are generally well-intentioned people such as Bill Maher (and me) on at least some of those fronts. Where would Trump or Maher be without politics as entertainment? Where would Maher be—or H.L Mencken or Mark Twain have been in their time—without availing themselves of the many social and financial benefits derived from contempt and disgust?

Third: Maher has been ridiculed for the warmth with which he described Trump—his laughter and all that. That kind of thing is sometimes accompanied by complaints about “humanizing” or “normalizing” Trump.

The “humanizing” and “normalizing” stuff has always been irritating to me. There is no need to humanize or to normalize Donald Trump, who is as normal as diabetic amputation and as human as a school shooting. Complaints about humanizing and normalizing have built into them a set of assumptions about the moral quality of the human and the normal that are simply not supported by the facts or by experience. Harvey Weinstein drunk in a hotel room at 4 a.m. trying to bully some young actress into having sex with him? Ecce, homo. Larry David implicitly makes the case against humanizing Hitler, but the inconvenient fact is that not only was Hitler human, he was a fairly common type of human: “How monotonously alike all the great tyrants and conquerors have been,” as C.S. Lewis observed in another book that Bill Maher really ought to read.

As I have already written, Maher and Trump are in the same business: They are entertainers, both very successful ones. And one of the things people who become major celebrities are very, very good at is making people like them. It is practically the job description. I have no idea whether, say, Gwyneth Paltrow is a good person or nice to know in private life, but I can tell you that I interviewed her for 15 minutes 30 years ago and the impression she made (intelligent, beautiful manners) has endured such that I’m writing about it today. I encounter celebrities from time to time in my line of work, and what almost all of them have in common is that they are charming. (As a rule, the bigger and more established, the more charming, whereas the marginal celebrities and the has-beens can be bitter.) I’ve been a guest on Bill Maher’s show a few times and have spent a little time with him, and he is, as you might guess, a perfectly gracious and amicable man, the prickly know-it-all he plays on television being one aspect of his personality but not the dominant one. Trump, I am informed, is much the same, a more polite and engaging version of the dim bully character he perfected in his years hosting a game show, performing as a pro-wrestling heel, and making cameo appearances in Home Alone movies and pornographic films.

It is not difficult to imagine Maher admiring Trump as il miglior fabbro—the superior craftsman, a cannier practitioner of the dark arts of celebrity. Maher has more native comedic talent than Trump does and far better writers—but look how much more Trump has made out of his modest endowments and with only the benefit of several hundred million dollars’ worth of inherited real estate! If Maher is guilty of something, it is of being so much a part of the same world as Trump that he is like one of those fish who doesn’t know that he is wet, and, for that reason, lacks the benefit of self-awareness and the consequent benefit of being able to maintain some critical distance—not from his subject but from his own reaction to his subject. There’s a difference between a man who overtips the waitress at Hooters and the one who thinks he is in love with her.

Here is a thing I read frequently in my correspondence: “You just hate Trump.” But I do not hate Trump—Trump is not good enough to hate. One must esteem something a little bit, at least, to hate it, because you cannot hate something that doesn’t have a moral endowment sufficient for being hated. It is not that Trump does not represent a serious phenomenon, but Trump is serious the way mosquitos are serious: Mosquito bites will kill something on the order of a million people this year, just as they did last year and will next year. When sharks are having a really big year, they kill half a dozen people worldwide, whereas mosquitos stack up corpses from the floors to the rafters around the world. But you cannot hate a mosquito—you can only swat him.

My feeling for Trump is not hatred but contempt. Contempt is not a particularly admirable emotion, and it is one that a more enlightened kind of man would resist better than I do, even—especially!—when confronted with that which is genuinely contemptible. I am sure that Maher has his reasons for resisting his natural inclination toward contempt in this case, and—who knows—one or two of those reasons may even be good ones. Of course, there also is the example of MSNBC’s ratings (partly recovered, yes, but having taken a beating) to think on—this isn’t 2017, and the market has changed.

Maher of course has the experience of having had a television show canceled on grounds of “You can’t say that!” And I would prefer to live with the sort of political culture (and media environment) where we didn’t do that sort of thing—where we did not indulge the desire to punish the way we do. One of the ironies here is that Maher’s critics resemble the Trumpists they despise in being too thoroughly dominated by that desire to punish, which leads us (and I do not exclude myself) in unproductive directions, and sometimes in dangerous ones. Maher’s attitude toward Trump is, of course, far too rosy, and his assessment of the political situation of which Trump is both a cause and an effect is, in my view, fundamentally mistaken. But calls to boycott his show—or to caricature him as a Nazi stooge, as Larry David has—strike me as having in reality very little to do with Trump or Trumpism, and as a tool for counteracting Trump and Trumpism, that sort of thing is somewhere between silly and positively counterproductive. It is not from the world of politics and negotiation but from the older world of taboo and anathema, which are homogenizing forces: “My disgust must also be your disgust.”

We could use rather less homogeneity in our public life and fewer forces pushing us toward stultifying conformism. I do not think I would have accepted Trump’s invitation. (I do not expect one to be forthcoming.) And I could make a good argument for declining. But I have never looked in the mirror and said to myself: “The world would be better off if everybody were more like me.” Most days, I’d like to be less like me myself. But here we are: Bill Maher’s social calendar is at variance with the private preferences of some number of Americans not named Bill Maher, and the fact that this has become a big news story probably says more about the state of our political culture than the fact that a talk-show host and a game-show host had a nice dinner (De gustibus, etc.) and a friendly chat.

Correction, April 30, 2025: William Makepeace Thackeray would have been alive in 1847, not 1947.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.