Last year, in Students for Fair Admissions (SFFA) v. Harvard, the Supreme Court effectively banned the use of race as a factor in college admissions. Since then, it’s been unclear what the fallout would be.

Would black and Hispanic enrollment at the nation’s most selective colleges fall dramatically? Would schools figure out ways of preserving diversity without considering race directly? Would some defy the ruling entirely?

As the Class of 2028 arrives on campuses nationwide, we are starting to get some answers. While different schools seem to have responded quite differently, all of the above possibilities likely came about to some extent.

The backdrop.

The key fact underlying this entire issue is this: There are, unfortunately, dramatic racial gaps in academic preparedness in America. As of 2023, a white SAT-taker was about four times as likely as a black one to score at least 1200 out of 1600—and about six times as likely to score 1400 or higher. An Asian test-taker, meanwhile, was roughly two and four times as likely as a white one to hit those same benchmarks.

This has obvious consequences for college admissions. The most selective colleges would admit relatively few African Americans if their processes relied upon academic measures alone. Before the SFFA decision, these colleges essentially papered over society’s racial gaps by giving large preferences to black (and to a lesser extent Hispanic) applicants.

Data shaken loose by the lawsuits suggested that black applicants to Harvard were about four times as likely to win admission as similarly qualified white students. At the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill—a lawsuit against the school was combined with the Harvard challenge—the boost was about 70 percent for in-state applicants and more than 10 times in the highly competitive out-of-state pool. This echoed research stretching back decades. A 2005 study of admission data from several top colleges, for instance, found that African American acceptances would decline about two-thirds if race were not considered.

Black enrollment at elite schools would clearly crater if racial preferences ended and nothing else changed. Yet that’s not quite the relevant counterfactual. SFFA effectively bars schools from considering race, but it doesn’t force them to admit students based on academics alone, or to remove race from their old processes while changing literally nothing else. “Race-neutral” paths to a diverse student body still exist.

In states that have banned racial preferences at public colleges in the past, many campuses have propped up their minority enrollment through policies that, for example, offer automatic admission to the top 10 percent of each high school’s graduating class—which, in effect, leverages school segregation to admit students from heavily minority schools. Another tactic is to use class-based affirmative action, which disproportionately benefits minority groups with lower average incomes. More deviously, schools might encourage applicants to write essays about their identities or experiences with discrimination, thus revealing their race (though in that case, schools are supposed to consider what the essay says about the individual, rather than race itself).

These strategies can have an impact, but the problem becomes extremely difficult at highly selective schools. In SFFA, Richard Kahlenberg—an expert witness on behalf of the folks challenging racial preferences—proposed a plan for Harvard that would have totally revamped the school’s selection process and still come up short demographically. As I summarized in a report for the Manhattan Institute last year:

Harvard would completely wipe out its racial, as well as its legacy, dean’s list and children-of-faculty-and-staff (LDC) preferences, and instead grant a large preference based on socioeconomic status (SES). Those current preferences take up a lot of space: nearly a fifth of all Harvard students in 2019 were estimated to be LDCs (though some would have been admitted even without preferences); racial preferences boost admissions chances four times for black applicants and 2.4 times for Hispanic ones. SES would be gauged not only at the level of individual families but also at the high school and census-tract level, where it would be measured by equally weighting three factors: parental income, parental education, and percentage of students speaking a language other than English at home.

These new preferences would boost the share of students considered economically disadvantaged (based on their neighborhood and their parents’ income and education) all the way from 18 to 49 percent. Though calibrated to boost black and Hispanic enrollment in particular—e.g., that’s a major benefit of measuring classmates’ and neighbors’ SES in addition to the applicants’ own—Harvard’s black enrollment would still fall from 14 percent to 10 percent in this scenario, while Hispanic enrollment would actually increase. The average SAT score of the incoming class would also drop somewhat. Responding to criticisms of the falloff in black students, Kahlenberg suggested Harvard could work in parental wealth and family structure, variables that would effectively target African Americans statistically but were not available in the data disclosed in the lawsuit.

At some point, one must ask how “race-neutral” this even is, since the whole point is to rig a school’s racial balance. But at any rate, before the ruling, the line from elite schools was that if they couldn't consider race directly, it would be practically impossible for them to keep minority enrollment at its previous levels without making unacceptable compromises. Many of them joined a brief in SFFA highlighting the failure of the challengers’ own Harvard plan to preserve black enrollment, as well as the fact that some of California’s most selective schools hadn’t managed to restore minority enrollment since the affirmative-action ban that took effect in the late 1990s.

A new workaround might be to reduce or eliminate the use of test scores, a popular trend during and after the pandemic. This would downplay racial gaps in academic performance and free up some more space for the use of other factors. As I wrote in The Dispatch earlier this year, that trend appears to be fading at elite colleges, as schools face the reality that test scores are a valuable predictor of college potential that can reveal otherwise hidden talent, and that lower-income students often fail to submit scores when it’s optional, even if their scores would help them. But many remained test-optional this admissions cycle.

So what actually happened?

The new data.

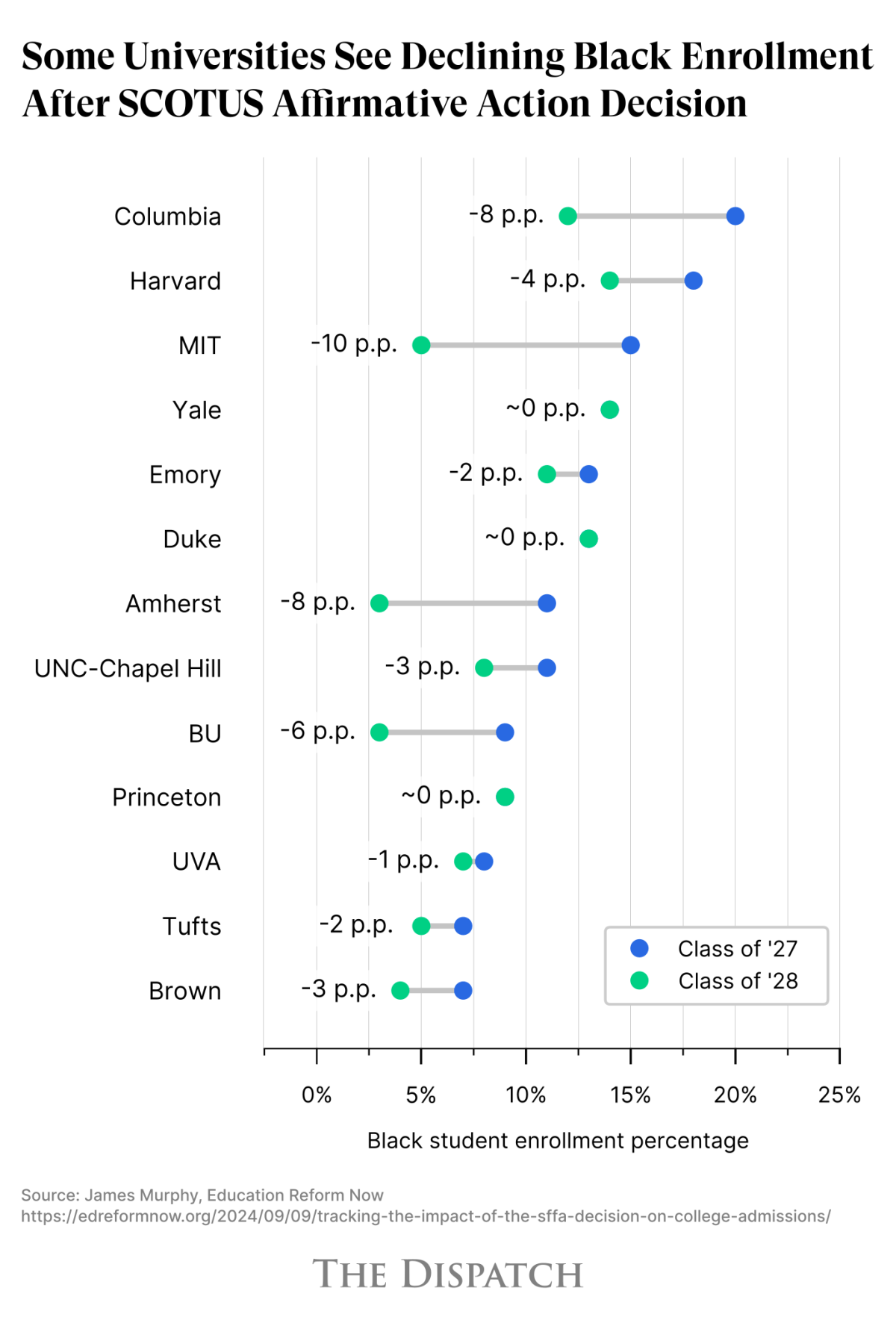

Over the past month or so, many colleges have released their racial breakdowns for the Class of 2028, at last giving a glimpse at the ruling’s impact. For simplicity and consistency, here’s a brief overview of black enrollment shifts between the Class of 2027 and the Class of 2028, from some elite schools that have released their data. (See this tracker from Ed Reform Now, which presents the numbers a little differently, for data on other racial groups and a few additional schools.)

Some of these schools had extremely severe drops, and yet some managed to hold their numbers steady. Without access to the latter group’s internal data, one can only speculate as to how they pulled it off—it must have been quite the feat, since Duke, Yale, and Princeton all signed the aforementioned legal brief arguing black enrollment would fall without racial preferences. What mix of variables did they use, and in what proportions, to get the same racial results without considering race directly?

Publicly, for what it’s worth, schools have generally said they increased recruiting and outreach efforts, boosted financial aid, worked with partners who could supply a pipeline of students from underrepresented groups, and used geographic data to boost students from places with, for instance, high poverty or low social mobility. Some schools have also deployed essay prompts likely to result in discussions of race. At Duke, the share of the class eligible for Pell Grants doubled to 22 percent. At Princeton, this statistic held steady (also at 22 percent) and Yale saw only a modest increase (from 22 percent to 25 percent), suggesting varying approaches to parental income.

Did any of them break the law? Again, schools may not use race itself as a plus factor in admissions, but, as a federal guidance document put it, they may still consider “how applicants’ individual backgrounds and attributes—including those related to their race, experiences of racial discrimination, or the racial composition of their neighborhoods and schools—position them to contribute to campus in unique ways.” It would take lawsuits or whistleblowers to find out which schools, if any, crossed that blurry line. Students for Fair Admissions has written letters to Duke, Yale, and Princeton putting them “on notice.”

Paths forward.

This is just one year’s data from a handful of schools, many of whose standardized test policies remain in flux. In the years ahead, comprehensive federal data will become available, and schools will likely learn from each other the best ways to adjust their admissions processes. So it’s still too early to say what the ultimate impact of the decision will be.

Regardless, it’s worth reflecting on the underlying problem here: the enormous racial gaps in academic performance. Both sides of the debate should sincerely commit to improving it. That could come about through improved K-12 education, such as through charter schools. Another idea, which my Manhattan Institute colleague Roland Fryer has proposed, is for elite universities to operate top-caliber high schools in impoverished neighborhoods around the country, recruiting and training the nation’s most talented poor children and ultimately bringing many to campus.

After all, if we didn’t have such yawning opportunity gaps, the affirmative-action issue would be moot.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.