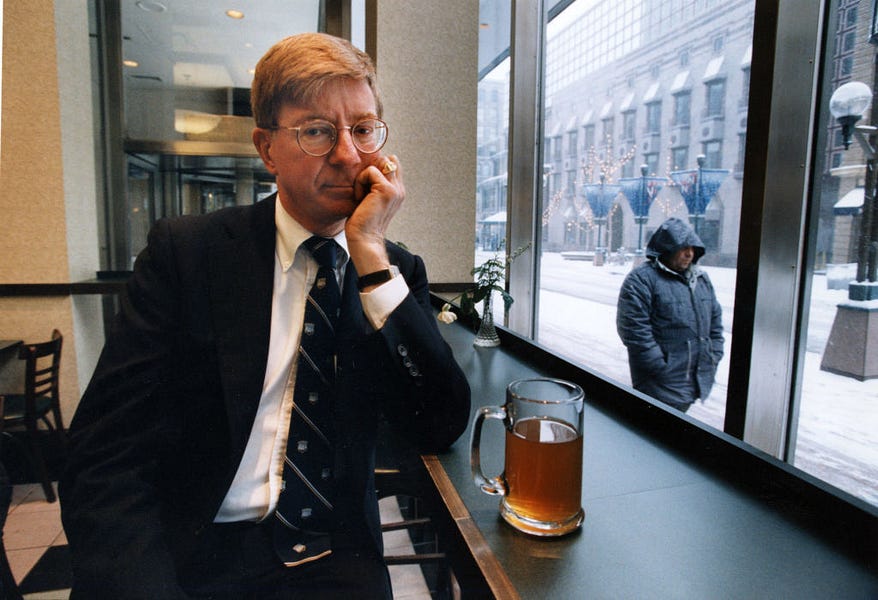

George Will is now 80 years old. Yet he appears to have entirely withstood the silent artillery of time. Outwardly, the contemporary Will is indistinguishable from the Will who delivered Harvard University’s Godkin Lectures in 1981. His hair has retained its fullness, he still dresses for every occasion in neatly cut suits and traditionally patterned ties, and his taste for fashionable eyewear endures. His command of language is as enviable today as it was when he began his syndicated column in 1974, while his erudition has only deepened.

Will’s political outlook, however, has altered throughout his life. At the time of the Godkin Lectures, his work was strongly influenced by British Toryism, and he regarded the American Founding with suspicion. Today, he is a self-professed classical liberal who believes conservatism is incoherent without the Founding at its root. In the late 1960s, he held similar views as a supporter of Barry Goldwater. Before that, he was a committed Democrat with progressive tendencies.

Recently, Will indulged me with a Zoom interview, in which we explored his intellectual development in greater depth. Avuncular in casual conversation, Will takes little pleasure in discussing himself at length. Indeed, perhaps his greatest asset as a columnist is his appreciation for the sheer variety of subjects in existence that are deserving of exploration. The breadth of Will’s journalistic oeuvre illustrates that life is infinitely richer than any individual, whatever his status in Washington.

Will was born to an academic family in Champaign, Illinois in 1941, and he grew up in a community of faculty children. His father, Frederick, and mother, Louise—a professor of philosophy at the University of Illinois and high school teacher, respectively—inspired him to cultivate intellectual interests. By the time of his enrollment at Urbana’s University High School, he had already been intrigued by politics. Devouring liberal publications played a significant role in shaping his early thought.

“In high school I began reading The New Republic, The Nation, and The Reporter magazine as it then was,” Will told me. “It’s long forgotten, but was quite excellent, sort of centrist Democrat.” Max Ascoli, who founded The Reporter in 1949 and campaigned against fascism in Italy earlier in life, became one of Will’s first major influences.

But Will was open to competing perspectives, and if the first issue of National Review had been released prior to his freshman year, the magazine may have convinced him to embrace conservative ideas even at this early stage. “I’m not sure I read National Review because National Review didn’t come along until late 1955,” Will said. Less than a decade later, it would help mold him into a firm Goldwaterite.

In September 1958, Will matriculated at Trinity College in Hartford, Connecticut. Shortly after arriving, he took a railroad trip to New York City and purchased a copy of the then-liberal New York Post upon reaching Grand Central Station. Thumbing through the paper, his eyes were drawn to a column by Murray Kempton. “I read it and said, ‘My gosh, what fun this guy’s having and what fun it is to read him,’” Will recalled.

Captivated by Kempton’s zest and inventive manipulation of prose, Will became addicted to his work. Kempton’s influence remains evident in all of Will’s writings, and Will maintains “undimmed enthusiasm for Kempton as a stylist and columnist. I write about 750 words a column, and no one ever did more than he did with 675. He understood there’s nothing more optional than reading a syndicated column, so it better be fun. And Murray Kempton made it fun.”

By 1960, Will had become known on campus through co-chairing Students for John F. Kennedy and serving on the editorial board of the Trinity Tripod newspaper. His social conscience had also led him to establish a new fraternity, QED, alongside 12 peers who opposed the national Delta Phi fraternity’s discrimination against black and Jewish students.

Peter Kilborn, who preceded Will as the Tripod’s editor in chief, stated in 1986 that Will was a “ranting, raving liberal” as an undergraduate and seemed destined to espouse socialism as he grew older. When I asked Will about this alleged vehemence, he disputed Kilborn’s assertions. “I rise to a point of personal privilege. I hope I’ve never been vehement about politics. I certainly wasn’t vehemently liberal.”

“I was a kind of standard issue Democrat,” Will continued. “But remember, Jack Kennedy in 1960—when the Cold War was probably the dominating issue and civil rights had not yet come to a boil—was to the right of Richard Nixon on national security issues. Partly because he invented out of whole cloth the idea of a missile gap that did not exist. But the distinction between left and right was hardly sharply drawn in 1960.”

Although some of Will’s Tripod columns may appear thoroughly progressive to modern eyes, he maintains that they should be understood as moderate in context. “I once wrote in an editorial that we were marching the wrong way in Vietnam,” he recalled. “This was, again, 1962. There weren’t a few thousand American advisers in Vietnam at the time.” Whatever feeling may have underpinned any of Will’s writings, he stresses the following point: “I still stand against vehemence.”

A particular belief that Will has adhered to without departure throughout his life is that God does not exist. And yet he ultimately earned a degree in religion from Trinity despite beginning his studies as a history major. “I read my Schleiermacher and Kierkegaard and all the rest,” he said. “It’s very interesting as a large part of Western culture. The great religions are durable because they address timeless anxieties and concerns. Real religions do three things: They enjoin, console, and explain. God created heaven and earth; do this, don’t do that; things are going to be all right. I’m very interested, just never persuaded.”

When I asked Will if he has ever considered conversion or encountered a uniquely compelling argument for faith, his answer was simple: “Nope.” He believes this inclination toward amiable atheism is a paternal inheritance. “I grew up in a secular household,” Will told me. “I don’t mean there was any preaching against preaching, it just never came up. My father was the son of a Lutheran minister. He used to sit outside Pastor Will’s study, listening to some of the more reflective parishioners trying to reconcile the doctrines of grace and free will. And my father became a philosopher. These are philosophic, not theological questions, he thought, and I’m the child of my father.”

Following his graduation from Trinity in 1962, Will attended Oxford University for two years as a Rhodes scholar. There, a pair of minor epiphanies transformed him into a conservative. Visiting the Berlin Wall enabled him to observe the tragedy of communism firsthand, while experiencing the failures of Britain’s experiment in statism granted him an appreciation for the virtue of American economic freedom.

“I saw the energies of a great people, the British people, being suffocated by the watery socialism of the Labour Party and the watery resistance to socialism on the part of the Conservative Party,” Will said of his time in England. As fate would have it, the beginning of Will’s studies at Oxford coincided with the publication of Milton Friedman’s Capitalism and Freedom and Hayek’s The Constitution of Liberty. “This is serendipity,” Will noted. “There were a number of people at Oxford at that time who had been at the Committee on Social Thought the University of Chicago, which had included Hayek, Friedman, and (George) Stigler for a while.”

Enthralled by such thinkers, Will traveled to London to visit the Institute of Economic Affairs, a think tank established in the 1950s to promulgate economic liberalism. He was eager to meet several scholars who were then laying the intellectual foundations for Thatcherism. Before arriving, Will made a new addition to his increasingly laissez-faire library. “I remember being at Dillon’s Bookstore near Bloomsbury,” Will said, “picking up Stigler’s wonderfully humorous book of essays called The Intellectual and the Marketplace, in which he argued that intellectuals don’t like markets because markets work so well without intellectuals. It was just a feast at that time.”

Upon his return to the United States in 1964, Will’s classical liberal conversion was complete. “I was in full-throated rebellion against the statism I saw in Britain, the social democracy that struck me as destructive,” he told me. That year, he cheerfully voted for Barry Goldwater and enrolled at Princeton University to pursue a Ph.D. in politics. As a doctoral student, Will read feverishly, almost to the exclusion of other activities. Doing so greatly enriched his understanding of government and history, although his broader worldview did not change.

After earning his doctorate in 1968, Will began teaching political philosophy at Michigan State University. He took a similar position at the University of Toronto shortly thereafter, but he found academia less fulfilling than expected. In 1970, he joined the staff of Sen. Gordon Allott, a Colorado Republican, and relocated to Capitol Hill. There, he wrote regularly on Allott’s behalf and began submitting book reviews to National Review whenever time permitted. William F. Buckley Jr. offered him a job with the magazine in 1972.

“He was the most accessible man, and he liked to collect young people he thought had promise,” Will said of Buckley. “I called him up one day and said, ‘You need a Washington editor of National Review.’ He’d never had one. And he said, ‘You’re right, I do. And you’re it.’” Under the pseudonym “Cato,” Will began writing National Review’s “Letter from Washington” column, and replaced Frank Meyer as the magazine’s literary editor. His writings remained classically liberal in orientation, and revealed a strong distaste for populism that would later cause him to abandon the GOP upon its embrace of Donald Trump.

In 1974, Will left National Review to join the Washington Post, where he began writing his biweekly syndicated column. As the decade progressed, a change gradually occurred in his perception of politics. While mainstream American conservatism increasingly emphasized individual liberty and the power of unfettered capitalism, Will stressed the importance of community and the need for government to actively mold a virtuous people. At the onset of the 1980s, he considered himself a Tory; a traditionalist driven by pessimism at a moment in which then-President Ronald Reagan promised a renewal of national prosperity.

When Will gave the first of Harvard’s Godkin Lectures on October 6, 1981, he warned that society would descend into hollow materialism and incoherent relativism without a strong federal government to “tutor its citizens.” Over the next year, he adapted the lectures into a book, Statecraft as Soulcraft (1983), and released a collection of columns titled The Pursuit of Virtue and Other Tory Notions (1982), which also explored such ideas. During our call, Will acknowledged that he experienced a political reckoning at this time, but argued that his thinking did not shift as significantly as it may appear in retrospect.

“I wouldn’t call it a change of mind,” Will said of his transition from classical liberalism to traditionalist conservatism. “I would say that I had become much more sensitive to the problem that Gertrude Himmelfarb, her husband, Irving Kristol, and others were to cite. And that is: Does classic liberalism provide for its own continuation, or does it live off the moral capital of a different age?”

Will had become concerned that classical liberalism was fated to descend into a “maelstrom of appetites” that would erode the habits, mores, and customs needed to sustain freedom. “If that’s all there is,” he told me, “then classic liberalism needs help. And the first thing is it must understand that it needs help.” Help, Will believed, could be found in a robust governmental framework designed to promote moral conduct, restrain self-indulgence, and provide for the public good.

Free market dynamism, Will contended in 1980, “dissolves” cultural conservatism. He feared the Reaganite agenda would beget an American people motivated solely by the pursuit of superficial gratification and inclined toward “other forms of indiscipline,” such as promiscuity and abortion. In Statecraft as Soulcraft, Will argued for a Disraelian welfare state that could serve as a bulwark against the atomizing effects of capitalism by supporting families and embodying “a wholesome ethic of common provision.” He also expressed approval of a military draft and endorsed the prohibition of drugs and pornography.

But when John Major became Britain’s prime minister in 1990, Will began to diverge from Toryism. “Remember, in 1979 and throughout the 1980s, the great British Tory was Margaret Thatcher,” he told me. “Now, it was famously said of Margaret Thatcher that she couldn’t see an institution without swatting it with her handbag. Not, I suppose, a conservative thing to do. But if the institutions had become captured by servants of statism, it was a conservative thing to do.”

For Will, Thatcherism was compatible with the political vision outlined in Statecraft as Soulcraft because it balanced a respect for virtue and the traditional duties of government with a more radical response to Britain’s socialist rot. American conservatism, meanwhile, seemed increasingly hostile to government in every regard.

“(Thatcher) said, ‘We have to have stern Victorian values,’” Will noted, industriousness and responsibility among them. “But she also said, ‘You people have been corrupted, and this is going to hurt. Get over it, stiffen your sinews, summon up the blood, and accept the fact that we’re going to have a little creative destruction here.’ Ronald Reagan came along with a big smile, and he said, ‘This is going to be fun, because the American people are inherently healthy and the government’s a problem—let’s get it out of the way.’ So there were two different temperaments, some different problems that conservatives thought they were looking at.”

Throughout the 1990s, the scope of American government expanded, and Will’s confidence in its ability to strengthen formative institutions decayed. In the early 2000s, George W. Bush spoke of reducing the size of government, but his embrace of compassionate conservatism allowed its growth to continue. “By that time, I’d been in Washington long enough to see the problem with interventionist government,” Will said. “It’s not that protectionism breeds crony capitalism or that industrial policy breeds crony capitalism. Both start from the get-go as crony capitalism.”

Will’s voracious reading had led him to develop an appreciation for public choice theory, particularly as it was defined in James M. Buchanan and Gordon Tullock’s book The Calculus of Consent (1962). “What they argued simply was government is never disinterested. Government is not the sole disinterested faction, it is a faction. It’s a faction with a police force, an army, a permanence, and the power to enforce its collection of resources. So I had a much more lively apprehension of the state than I had in 1973 when I began as a columnist.”

During the Bush era, Will recommitted himself to classical liberalism; the increasingly imperialistic nature of the presidency and passage of two particular laws convinced him that government had become absurdly bloated and invasive. Firstly, in 2002, the “McCain-Feingold (campaign finance) law did something that never occurred to me the Congress would have the audacity to do, or that the Supreme Court would ratify, which it largely did at first,” Will told Reason in 2013. “And that is, Congress, which is to say incumbent legislators, passed laws limiting the content, timing, and quantity of political speech about incumbent legislators.”

The next year, Bush passed the Medicare Modernization Act, which introduced an entitlement benefit for prescription drugs. This, Will told me, was “the first large entitlement program without a funding source. Bush said, ‘We’re gonna promise you this, and we’ll just not worry about how to pay for it.’ By this time, it had become clear that we had a fundamentally unsustainable entitlement structure that was going to breed all the bad habits that are writ large in the events of 2021.”

“We have what’s now called modern monetary theory,” Will continued, “which is the belief that if you have your own money, you can spend as much as you want, as long as interest rates are lower than the rate of growth of government. Democrats praise modern monetary theory and practice it, Republicans deplore it and practice it. There’s not a dime’s worth of difference between the two of them in terms of fiscal propriety.”

At the time of Barack Obama’s election in 2008, Will’s irritation with Washington had never been greater. His opposition to the intrusiveness of the state deepened, animated not only by an aversion to the rampant spending and “dependency agenda” pursued by the new administration, but a belief that entrenched bureaucracy was stifling the entrepreneurial essence of American life. Through this disillusionment, Will developed an admiration for the Tea Party’s constitutional activism and the writings of Reason editors Nick Gillespie and Matt Welch. Government, he concluded in a column praising their book The Declaration of Independents (2011), usually has no justification for interfering with market transactions and the lives of individuals—even, perhaps, in the realm of drugs.

Will continues to resist branding himself a libertarian despite these sympathies. “I would call myself a classical liberal, which is not quite the same thing,” he told me. Now, however, he regards classical liberalism as a distinguishing characteristic of American conservatism. “It’s a little late in the game for us to have a terminological dispute about this. European conservatism was, from its birth, concerned with hierarchy, with stability, with a kind of resistance to uncontrolled change. That’s not what American conservatives do. American conservatives say, ‘No, actually, what we like is the churning that comes with a market society.’”

“It’s been well said that the story of the Bible reduced to one sentence is, ‘God created man and woman and promptly lost control of events,’” Will continued. “Conservatives say, ‘Good, we don’t want events controlled.’ That’s the whole point. That closes the future, that empowers the status quo and the big battalions that are strong enough to manipulate the government in defense of the status quo.”

Although the solvent of dynamism concerned Will in the 1980s, he now considers it fundamental to American life. The Conservative Sensibility (2019), his latest book, further inverts the argument presented in Statecraft as Soulcraft by asserting that the welfare state has corroded the family unit and encouraged socioeconomic stagnation. Will principally cites Hayek’s “fatal conceit” to justify his new position, arguing that “markets are mechanisms for generating and collating information that only market processes can produce.” Economic freedom, Will told me, is successful and necessary because it “minimizes the inevitable transaction costs of government.”

This disposition also compels Will to take a more pragmatic view of various social issues that previously alarmed him, including pornography and prostitution. “Pornography, that train has left the station. The internet has made pornography ubiquitous and universally acceptable, so we have to find other ways to combat its malign influence. Prostitution we have essentially legalized. People deny this, but it can be zoned into particular parts of cities. Again, the internet’s a big help for those who want sex workers to be able to ply their trade. Society has accommodated those issues in a way that does not involve the United States government in a series of domestic Vietnams.”

As for drug liberalization, Will recognizes distinctions between substances (“Cocaine leads necessarily to the degradation of life in a way that marijuana or martinis do not,” he told me). But his view on all of these matters is ultimately the same: Stringent restrictions cannot be justified as a matter of principle. “These are powerful human appetites and they’re going to be accommodated,” Will said. “They can be channeled in some ways, they can be tamped down in some ways, they can be quarantined in some ways. But there they are. And it’s not particularly conservative to think that you’re going to extinguish these appetites.”

During our call, Will insisted that his renewed enthusiasm for capitalism and more liberal attitude toward indulgences do not entail a rejection of Statecraft as Soulcraft’s central thesis: “The subtitle of the book is Statecraft as Soulcraft: What Government Does. Not what government ought to do, but what it can’t help but do.”

In the book, Will observes that “statecraft need not be conscious of itself as soulcraft; it need not affect the citizens’ inner lives skillfully, or creatively, or decently. But the one thing it cannot be, over time, is irrelevant to those inner lives.” Government, then, simply by enforcing laws and norms, inescapably shapes public morality.

“Any regime, by what it affirms, stigmatizes, and prescribes has a soulcraft effect,” Will said. “I give the example of the 1964 and ‘65 Civil Rights Acts. The government said, ‘A lot of white people don’t want to go to soccer or go swimming with blacks or sit next to them on the bus. Too bad. Do it anyway, because it’s not only fair to them, it’s good for you. This will change both sides.’ And I think it was a resounding success.”

“In Statecraft as Soulcraft I went so far as to say that America was in a sense ‘ill-founded’ because it had not paid sufficient attention to preserving, nurturing, and replenishing its moral stock,” Will recalled. Now, he believes that an open economy, buoyed by institutions such as courts and schools, instills virtue in its participants with an effectiveness no other system could match.

But Will also feared that the churning of capitalism would fracture communities while disintegrating common interests and activities. Arguably, he was correct. Americans today have never been more isolated; they are deprived of real connections and increasingly exist within cultural cocoons. Nonetheless, Will maintains that the immense human benefits of capitalism outweigh its casualties. “I did not in Statecraft as Soulcraft sufficiently appreciate the extent to which a market society, stressing lightly governed spontaneous order and cooperation of voluntary groups contracting together, doesn’t just make us better off—which it manifestly does—but makes us better, by making us a more cooperative and polite society.”

Some conservatives will be delighted by the direction Will’s philosophical journey has taken in recent years. Others will resent it, preferring instead to savor his more Burkean writings of days past. Progressives, meanwhile, may only read any of his work for the sake of acquainting themselves with ideas antipodal to their own. Perhaps this is what makes Will’s career so endearing: Anyone, regardless of persuasion, can derive inspiration from it.

For young conservatives who wish to be known in the United States, Will’s advice is simple: “Read.Read Hayek, Friedman, Schumpeter, Matt Ridley. The world belongs, in the end, to those who know things, and who know how to argue.” His own life stands as decisive proof of that statement.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.