College students and recent grads are favored targets of the think piece mill. In the mid-2010s, Time targeted the millennials for being “lazy, entitled narcissists.” More recently, young people are being singled out for being functionally illiterate. The November 2024 issue of The Atlantic featured a viral exposé of elite college students who can’t finish or understand books, with one Georgetown University professor admitting that most Hoyas “have trouble staying focused on even a sonnet.” The blame is usually placed—by The Atlantic and others—on the pandemic, the No Child Left Behind Act and Common Core, and those damn phones.

It’s undeniable that social media and test-based school curriculums have likely contributed to the death of the literary hobby. But I believe the miseducation of American youth began when we abandoned the value of self-education through literary pursuit. When will we stop bemoaning the education system and Big Tech, and start taking responsibility for our own failures of erudition?

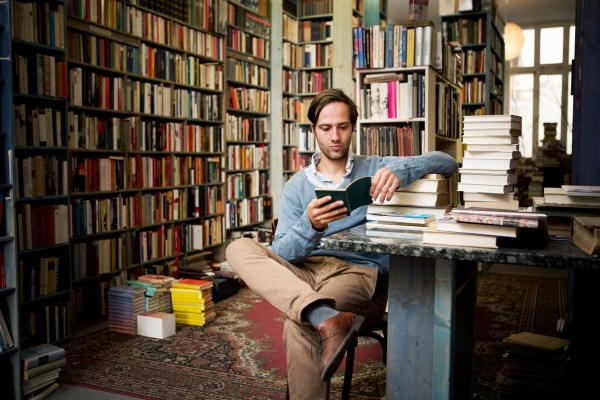

For all intents and purposes, I am well-educated. I have a Bachelor of Arts from Tulane University. I was always on the dean’s list. Growing up, I considered myself an avid reader. Yet, up until a month ago, I had never read The Great Gatsby. No one ever assigned me Moby Dick or Pride and Prejudice. When I started work at a major think tank a few days after graduation, the realization set in that I was vastly underprepared for the level of intellectual rigor required for watercooler conversations. By the end of my first week of work, three people told me Middlemarch was their favorite book. I had never heard of it.

It would have been easy to shake my fist and curse the course crafters for the sorry state of my literary repertoire, but nobody had actually stopped me from reading the great works. In other words, it was at least partly my own damn fault—and it would be my own job to fix the problem. So, I committed to reading what I perceived to be the most referenced works of literature—commonly referred to as the “great books.” And once I started, I gained access to what felt like a whole new method of understanding the human experience.

For example: When I first moved to Washington, D.C., following a childhood in the Rocky Mountains and a stint in the bayou for college, I had a tremendously difficult time adjusting to life out East. I couldn’t put the sense of otherness I felt into words, until F. Scott Fitzgerald’s Nick Carraway did it for me:

I see now that this has been a story of the West, after all—Tom and Gatsby, Daisy and Jordan and I, were all Westerners, and perhaps we possessed some deficiency in common which made us subtly unadaptable to Eastern life.

These lines didn’t reveal the secret to happiness inside the Beltway, but they did make me feel less alone. And that means something. In one recent survey of members of Generation Z, 73 percent said they felt alone “either sometimes or always.” Of course, the fact of loneliness isn’t a new problem—but it’s unique in this day and age for two reasons. One, because feelings of loneliness are seemingly much more widespread and affecting. And two, because we—in our reliance on short-form, often shallow media for entertainment—have an absence of someone else to articulate those feelings for us. It’s one thing to view the experience of a TV character or a #relatable influencer and smile in reaction; it’s much more profound to see thoughts and emotions you struggle to express put to page. So I don’t think the kids need, en masse, more therapy; they need more books.

Not just any books, however. They need great books. Many bestselling novels like The Silent Patient or A Court of Thorns and Roses lack serious mediation on the human condition. They are strictly linear narratives chock full of visual descriptors in seeming attempts to fill a page. The majority of the bestsellers of today fall into three categories: soft-core pornography, written attempts to capitalize on the true crime craze, and a hyper-fixation on “identity” and representation for representation's sake. But it’s not the genres themselves that are the main problem of many popular books; with few exceptions, contemporary fiction makes little to no attempt at articulating complex emotions or invigorating the banal.

In contrast, I recently spent a Saturday with Slaughterhouse-Five. At risk of defaming Mr. Vonnegut, Slaughterhouse covers all three categories of contemporary fiction. There’s spacetime erotica, horrific violence, intense displays of human depravity, and cross-cultural discourses. Yet it is one of the most tender novels I have ever read. Vonnegut captures the senseless nature that life can seem to have in the midst of suffering, something many young people have a difficult time reconciling. One of the primary aims of Slaughterhouse is to help its readers make sense of this dissonance. It’s a draught for existential dread. As Vonnegut says: “So it goes.”

Loneliness is not the only scourge on youth today; hustle culture and social media have caused the value of the individual to be determined more and more by vapid metrics of status and maximization. Your worth and intelligence is measured by your LinkedIn experience or the U.S. News & World Report ranking of your college. You don’t get any clout for finishing Crime and Punishment. Why would you bother reading The Catcher in the Rye when you could master day trading instead?

In order to revitalize a literary culture in America, there must therefore be some tangible value in spending precious time and mental capital on reading. That argument is hard to make to the finance bros and future Zuckerbergs of America—after all, the value in great books has nothing to do with success as defined by wealth or a major tech breakthrough. No, the merits of engaging with great literature as a hobby is the priceless notion that you are not alone in your suffering, heartbreak, and internal turmoil.

The Germans, of course, have a word for this process of self-education that achieves a therapeutic aim: Bildung. The 18th-century philosopher Wilhelm von Humboldt meditated on the word, stating that education ought to be viewed as a life-long pursuit rather than a formative instruction. Moreover, von Humboldt understood that man required reflection on the human condition in order to avoid the crushing despair associated with being alive. As he wrote:

[Man’s] nature drives him to reach beyond himself to the external objects, and here it is crucial that he should not lose himself in this alienation, but rather reflect back into his inner being the clarifying light and the comforting warmth of everything that he undertakes outside himself. To this end, however, he must bring the mass of objects closer to himself, impress his mind upon this matter, and create more of a resemblance between the two.

In the Age of Information, we have failed to heed von Humboldt's warning to avoid alienating external stimuli. We reach for inflammatory politics, trending aesthetics, and fungible commodities. But by opting to reach for the compositions that formed our mutual ancestral consciousness—that is, great books—we can reacquaint ourselves with that clarifying light and comforting warmth. Reading a great book isn’t as easy as staring at your phone. I’ll admit it; it’s not as much fun either. But once you get past the temptation of cheap convenience and watered-down pleasure, the pursuit of great literature is one of low risk and exceptionally high reward.

Revitalizing great books programs in schools across the country is an honorable idea. However, institutional change, especially education reform, is easy to call for but difficult to implement. Call me a cynic, but I also don’t think simply assigning the great works will be enough to counter the philistine phenomenon. After all, any college student worth their salt can Chegg their way through a book and ChatGPT an essay.

Instead, great books must be sought out and encouraged outside the classroom, and I’m less of a cynic when it comes to independently revitalizing literary culture. After all, many young people are still falling in love with literature—last week, I discussed Larry McMurty’s Lonesome Dove with a few friends over beers and cheese fries—and we all got there on our own.

When I started my highfalutin’ research gig, I was inculcated into a culture where a familiarity with literature was required to socially thrive. Critics may call it elitism, but that culture was what pushed me to better my intellect—and the elitist argument would be to dismiss the notion that the masses can or will engage with literature. Great books are for everyone, and this idea should be as commonplace as other ambitious social norms. Integrating great literature into your life is a lot like eating your veggies; it’s less pleasurable than eating mac and cheese for every meal, but alas, it must be done. And eventually, you get used to it, for the better.

Ultimately, the choice to engage with great books will be an independent one, and not everyone will choose to do so: You can lead the student to Tolstoy, but you can’t force him to read.

Still, I’m certain that those who do choose to do the hard thing by reading the great books will reap the benefits—less loneliness, assuaged anxieties, and victory over cultural entropy. Gen Z will always have its own problems. But illiteracy and alienation don’t have to be among them.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.