Americans are arguably as politically engaged as they have been in over a century. That’s encouraging news if our politics represents something substantial: Competing ideas, policies, and visions of the future.

But what if our political debates weren’t substantive—plenty of clashing, but no clash of ideas?

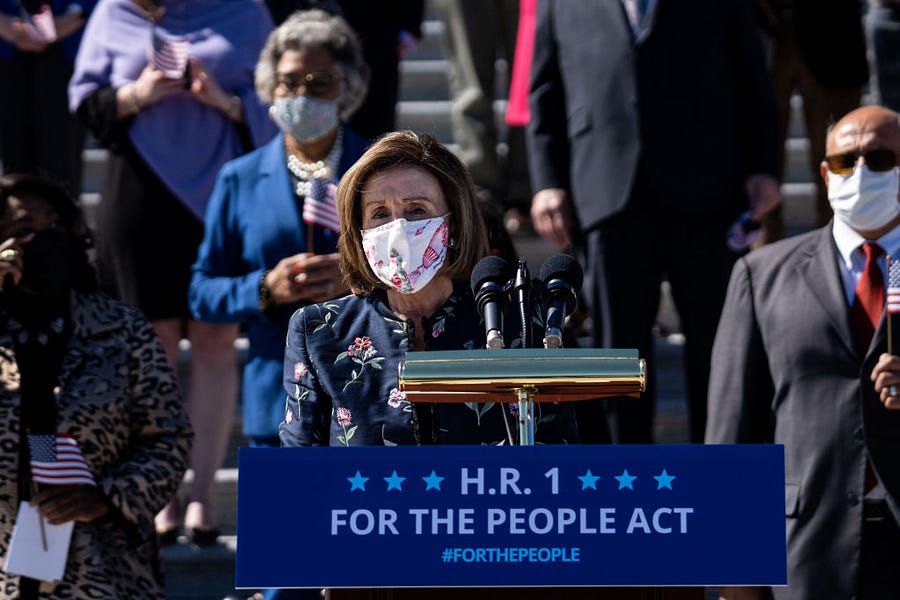

If you liked the bitter polarization of the 2020 election, you’ll love the idea of subjecting not just election ads, but any ads about policies and ideas to speech restrictions and personal disclosure mandates in the misnamed For the People Act (H.R. 1).

While most coverage has focused on H.R. 1’s election-related provisions about publicly funded campaigns, early voting, and redistricting, almost a third of its nearly 800 pages targets speech rights. Concerns over these First Amendment restrictions are why groups as diverse as Americans for Tax Reform and the American Civil Liberties Union have come out in opposition to these measures.

The new federal rules would impose onerous requirements on nonprofits, chill free speech, and subject citizens to harassment and intimidation. They risk turning every policy deliberation into a tribal fight over who is on what team instead of robust discussions about visions of America’s future.

Under H.R.1, every TV, radio, or online ad talking about principles and policies—whether it’s about economic recovery, health care innovation, equal justice, human rights, or the many other beliefs and concerns Americans join together to address—would be forced to list the names of the individuals who support the organizations that paid for it as well as filing their private information in a searchable government database. It’d turn issue advocacy into bad pharmaceutical ads. (Warning: The people who support this idea may include people that are not in your tribe.)

The personal information doesn’t tell you about whether the ideas are good or bad. It simply tells you that Mr. X or Ms. Y cares about the cause—or even just generally agrees with the organization’s views. So, if you don’t like Mr. X, you can close your mind. No need to think about or respond to the nuance of an issue or the complications of policy.

H.R.1 would have us focus our political energies on who is on which team, not what a group is proposing and whether its position may—or may not—have merit.

In a seminal 1950s social psychology study, researchers discovered that even people with a lot in common could be easily polarized simply by dividing them into teams and setting up an “us vs. them” environment.

The Robbers Cave experiment divided a group of fifth-grade boys from similar backgrounds into two groups at a summer camp. As a New York Times article described the outcome: “Within two weeks, they devolved into insulting and threatening each other, to the extent that the experimenters had to intervene. Their arbitrarily assigned group identities were enough to stoke open conflict among them.”

H.R.1 sets our politics up for a perpetual Robbers Cave experiment where we’re divided by teams rather than united in deliberation.

Privacy rights enable people not to play to type. They allow people to support ideas that might surprise their own tribe. It allows them to support policies that even the politicians they generally support might not like.

Forcing people to disclose the groups they join and causes they support does the opposite. It discourages nontribal thinking and forces us into our lanes.

Study after study confirms Americans of all stripes are tired of the divisiveness that dominates national conversation. That tenor intensified last year. The 2020 president election has been called the “Seinfeld election,” in honor of the timeless sitcom that was famously “about nothing.” That’s not to say it wasn’t highly consequential. It was. The stakes were high, and voters felt it. But the campaigns focused less on making the case for big ideas and more on speaking narrowly to people on their existing teams.

Legislation that encourages us to focus on a list of names instead of the ideas being proposed stifles debate and drives us further apart instead of allowing us to come together and respectfully challenge each other to solve the biggest challenges we’re facing.

The election of 2020 was perhaps the most polarizing one in decades. H.R. 1’s political speech regulations risk duplicating that environment in perpetuity. Whoever you voted for, surely we can agree that we should leave the politics of 2020 behind.

Casey Mattox is vice president for legal and judicial strategy at Americans for Prosperity

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.