With malice toward none; with charity for all; with firmness in the right, as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in; to bind the nation’s wounds; to care for him who shall have borne the battle and for his widow, and his orphan—to do all which may achieve and cherish a just, and a lasting peace, among ourselves, and with all nations.

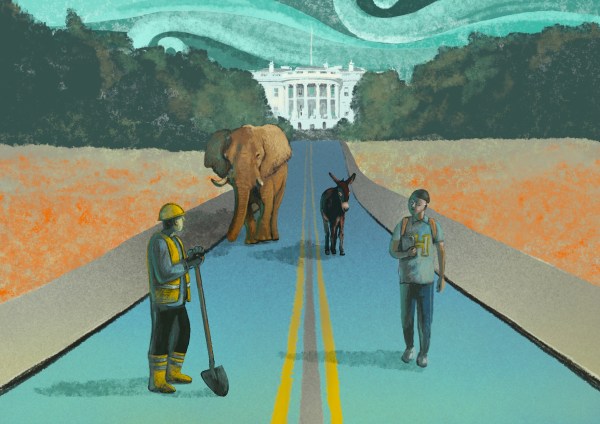

Could Lincoln’s beautiful and moving sentence of goodwill and national unity ever be more timely than it is today, as we face probably the most divisive election since the Civil War? Can this golden sentence by Lincoln, our consensus greatest president and greatest political man, guide us, or at least advise us, in these less-than-golden times?

These words were the parting wishes and hopes of his second inaugural address, delivered on March 4, 1865, shortly before the end of the Civil War. Lincoln was looking toward what would come after. He had a policy of post-war reconstruction that aimed to secure the freedom of the newly emancipated and effect a non-punitive reconciliation of the warring sections. A tall order. He hoped to effectuate it through offering lenient terms to most of the Confederate rebels while at the same time requiring that they recognize and promote reasonable aid (e.g., education) to the freedmen. Others had other ideas. Many of the Republicans in Congress sought a much more punitive peace—punishment and civil disabilities for all who had participated or overtly sympathized with the rebellion, as well as according much stronger protections to the formerly enslaved.

Lincoln’s speech promoted his more conciliatory policy by telling a different story about the meaning of the war from the one that he had told earlier at Gettysburg—and much different from the one that seemed to inspire his Congressional opponents. That last is well captured in the most lasting cultural product of the Civil War: the “Battle Hymn of the Republic.” Although stirring, it was a song animated not by the spirit of charity but rather more by malice. It certainly displayed “firmness in the right” to the point of self-righteousness as shaped by utter conviction of God’s partisanship for the Union army and with the Northern cause. Lincoln countered with a different song. The war did not signify God’s unconditional support for the North. Rather, it was a punishment, visited on both North and South for the sin of slavery, a sin in which the entire nation shared. God’s already imposed punishment meant that the proper attitude was humility not self-righteousness, charity not harshness, all combined with a firm but pragmatic commitment to freedom of the newly freed.

Can Lincoln’s words guide us? Did it guide his countrymen in 1865 and beyond?

Clearly not. Reconstruction policy turned out to be closer to what his Congressional opponents sought, with long-term mixed results. It is only a slight exaggeration to say that the outcome was the very opposite of what Lincoln sought—continued bitterness between the sections and the imposition of a regime of white supremacy and black subjection only marginally better than slavery.

But, of course, this history was no fair test of Lincoln’s policy, for his death on April 15, 1865, not long after his second inaugural, meant that he had no chance to lead the nation along his path.

The frame of heart and mind Lincoln displayed in his second inaugural address, of course, did not magically appear toward the end of the war. Even before it, he promoted similarly conciliatory ideas. In one of his earliest addresses, he compared an earlier generation of temperance reformers with a newer type that had emerged only a few years before. These new reformers were themselves for the most part reformed drunkards. Rather than addressing the intemperate with anathema and moral blame, the new reformers approached them with charity and understanding. Lincoln believed they owed their amazing success to their generous and non-demonizing attitude and rhetoric.

In his own anti-slavery political activity, Lincoln took to heart their example. He was careful to separate the sin from the sinner, maintaining the possibility of fruitful conversation and rational conversion. A good example came in his 1854 Peoria Address:

Before proceeding, let me say that I have no prejudice against the Southern people. They are just what we would be in their situation. If slavery did not now exist among them, they would not introduce it. If it did now exist among us, we should not instantly give it up. This I believe of the masses north and south.

The speech evinced not denunciation and depreciation, but rather recognition of the dignity of the opponent. It similarly noted a common problem in need of a solution—and an invitation to find that solution to an admittedly very difficult problem.

Lincoln’s pre-war political activity was marked by the spirit of his post-war hopes—and yet, he failed. In the medium run he aimed to prevent the spread of slavery into areas where it was not already established. In the longer term, he sought to move toward the abolition of slavery in the nation, all the while preserving peace and the union. That didn’t happen. His conciliatory language and moderate policies did not prevent the South from seeing him as a dangerous enemy bent on destroying their way of life. As a result, they took his election to be a signal that their safety and ability to build the future they desired required a national divorce. His unwillingness to accept Southern secession led to Northern resistance and the result none of the parties sought. As he put it in his second inaugural: “And the war came.”

We must try to understand the reason for that failure and its implications for the possibility of Lincoln’s speaking to our situation. By the late 1850s he knew or strongly suspected that the South considered the Republican Party’s intransigent opposition to the spread of slavery into the territories to be a denial of their constitutional rights and a signal that they no longer had an acceptable place in the Union. Lincoln’s Illinois Senate opponent, Stephen Douglas, fashioned a policy called “popular sovereignty.” According to the idea, each territorial legislature would decide whether to permit slavery or not, thus removing the issue from Congress and national politics. He had reason to expect this would be more acceptable to the South and thus more likely to preserve the Union—as well as more likely to end or at least limit slavery in the long run. Yet Lincoln, for all his charity and conciliation and moderation, opposed Douglas’ policy with all his might, thereby knowingly courting the result that occurred—the war.

“Rather than addressing the intemperate with anathema and moral blame, the new reformers approached them with charity and understanding. Lincoln believed they owed their amazing success to their generous and non-demonizing attitude and rhetoric. In his own anti-slavery political activity, Lincoln took to heart their example.”

The explanation for Lincoln’s behavior—and thus of the limits of charity and moderation—was spelled out in his famous House Divided speech, delivered on June 18, 1858. If the nation followed Douglas’ policy, Lincoln reasoned, the likely result was a nation wholly poxed by slavery. The nation faced, he very plausibly concluded, a future of being either all slave or all free. The issue of slavery was not compromisable except in the short run, and short-run compromises were most likely to lead in the longer run to the unacceptable result of the nation born in a dedication to human freedom and equality becoming a nation devoted to human slavery. Insisting on a policy of stopping the spread of slavery was necessary to preventing that future, even if it meant the failure of his conciliatory moderation.

Lincoln’s failure was thus a function of the particular issue that divided the nation and had a peculiarly either/or character. Not all issues are like this. What about the issues that now divide us?

Is immigration an issue comparable to “all slave or all free”? Is there no common ground on which negotiation can occur? Is the political-economic issue of free trade versus tariffs like the slavery issue? Are any of the foreign policy issues that we face like slavery? Probably the issue most like the either/or of slavery is abortion. It is divisive indeed, but we must notice that abortion has been with us since at least the early 1970s and had not caused the level of polarization we now experience.

Our issues, it seems, are amenable to a politics of civility, if not charity in the Lincolnian sense. Why have we not achieved that? The first answer is that the character of the issues is a necessary but not sufficient condition for a civil politics. Consider the 2020 election of President Joe Biden. He came into office with a promise of civil unity, but despite the many good things he accomplished he is leaving office with the nation more polarized than it was. It must be said that he is partly responsible for this. He won election as the moderate, unity-seeking candidate, but soon became inflamed with the hope to be the next or the greater FDR and signed onto a policy agenda that sat well outside the promise of moderation the nation had seen in his candidacy.

Political leaders must have not only the Lincolnian words in their hearts, but the skill and will to act accordingly. A much larger failure than Biden in that regard is Donald Trump, who constantly displays a self-aggrandizing and entirely self-centered approach to political leadership. In my opinion, his passing from the scene in one way or the other is a sine qua non of our seeing a great America again. He sows division and malice wherever he goes and, given his mysterious ability to mesmerize his followers and infuriate his opponents, we will reap what he sows until he leaves the scene.

With the right leadership and our manageable issues, then, let us see if Lincoln’s rhetorical and moral advice might not aid us in our attempts “to bind the nation’s wounds” and “to do all which may achieve and cherish a just and lasting peace, among ourselves, and with all nations.”

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.